A Practical Guide to RNA-seq Differential Expression Analysis: From Candidate Genes to Confident Conclusions

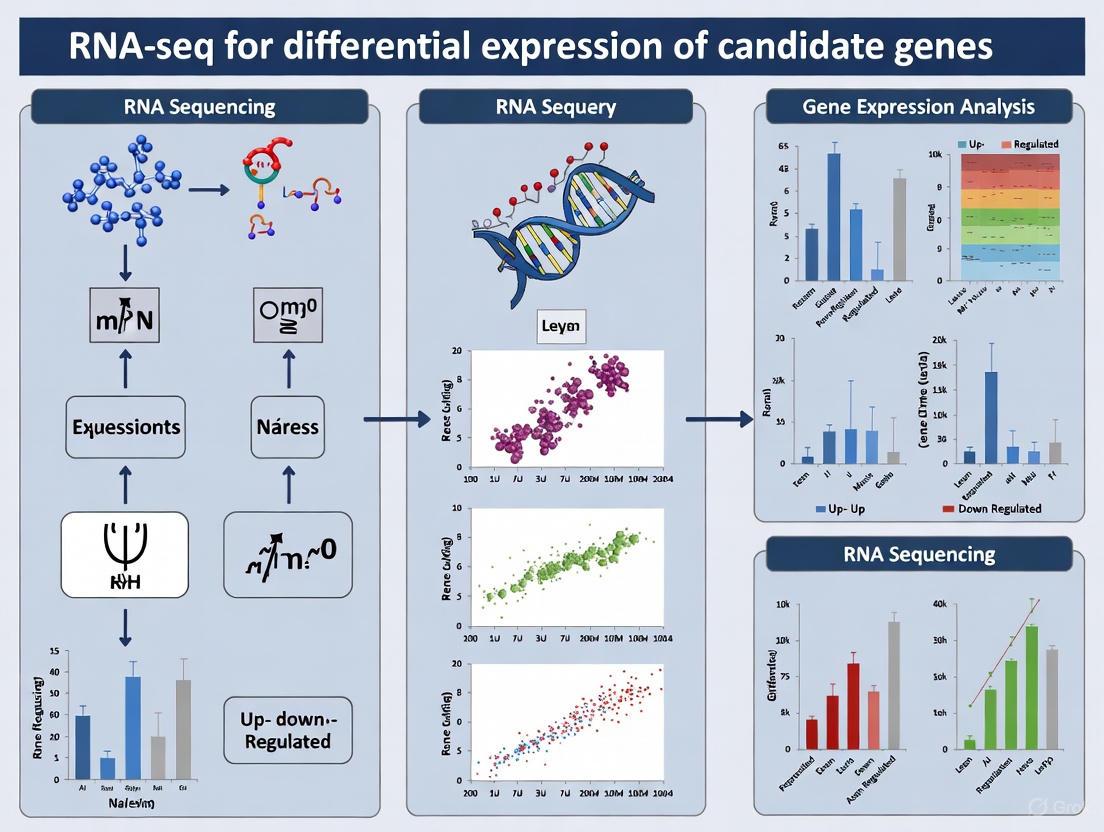

This article provides a comprehensive, decision-oriented guide for researchers and drug development professionals conducting RNA-seq differential expression analysis on candidate genes.

A Practical Guide to RNA-seq Differential Expression Analysis: From Candidate Genes to Confident Conclusions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, decision-oriented guide for researchers and drug development professionals conducting RNA-seq differential expression analysis on candidate genes. It covers the complete workflow from foundational principles and experimental design to advanced methodological execution, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and rigorous validation of findings. By synthesizing current best practices and comparative tool assessments, this guide empowers scientists to design robust experiments, select appropriate computational tools, optimize analytical parameters, and confidently interpret results for impactful biological and clinical insights.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Experimental Design for Robust RNA-seq

Within the framework of RNA sequencing for differential expression analysis, the transformation of complementary DNA (cDNA) into a digital count matrix constitutes a critical computational phase. This process converts analog expression signals into quantitative data that powers statistical discovery of candidate genes [1]. The integrity of this step directly influences the accuracy and reliability of all subsequent biological interpretations, making it a cornerstone of robust transcriptomics research [2]. This guide details the experimental protocols and key decision points for researchers and drug development professionals executing this core component of the RNA-seq workflow.

Key Stages from cDNA to Count Matrix

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Following cDNA synthesis, the library is prepared for sequencing. This involves fragmentation of cDNA, size selection, and the ligation of sequencing adapters containing sample-specific barcodes to enable multiplexing [3]. The choice between stranded and non-stranded library prep is crucial; stranded protocols preserve the information about the originating DNA strand, allowing for the precise identification of antisense transcripts and enhancing the annotation of genes in overlapping regions [4] [5]. The final library is then sequenced on a high-throughput platform.

Read Alignment and Splice-Aware Mapping

Sequencing produces raw read files (typically in FASTQ format), which must be aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome. For eukaryotic mRNA, this requires specialized splice-aware aligners capable of mapping reads that span exon-exon junctions, a challenge posed by intron splicing [6] [7].

Alignment Strategy Decision Matrix:

| Strategy | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Align against genome (Splice-aware) [6] | Most versatile; enables novel transcript, splicing variant, and fusion gene discovery. | Computationally intensive. | Comprehensive analysis, novel discovery. |

| Align against transcriptome [6] | Simpler, faster alignment. | Limited to known annotations; cannot detect novel genes or variants. | Well-annotated organisms, targeted studies. |

| Pseudo-alignment (e.g., Salmon, Kallisto) [6] | "Blazingly fast"; provides accurate quantification. | Cannot detect novel transcripts or genomic anomalies; quantification-focused. | Rapid gene-level expression quantification. |

Commonly used splice-aware aligners include STAR, HISAT2, and TopHat2 [6] [7]. The alignment output is a Sequence Alignment Map (SAM) or its compressed binary version (BAM) file, cataloguing where each read maps within the genome.

Quantification: Generating the Count Matrix

The aligned reads are then assigned to genomic features (e.g., genes, exons) to create the count matrix. This step determines the raw expression value for each gene in each sample.

Tools for Read Quantification:

| Tool | Method | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| featureCounts (Rsubread) [8] | Alignment-based | Fast and widely used for generating count matrices from BAM files. |

| HTSeq [8] | Alignment-based | Provides precise counting rules for handling ambiguous reads. |

| summarizeOverlaps (GenomicAlignments) [8] | Alignment-based | An R/Bioconductor function for flexible read counting in R. |

| NCBI Pipeline [9] | Alignment-based | Uses HISAT2 for alignment and featureCounts for quantification on submitted human/mouse data. |

The result is a count matrix—a table where rows represent genes, columns represent samples, and each cell contains the raw number of reads assigned to that gene in that sample [8] [9]. This matrix is the fundamental input for differential expression analysis tools.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from sample to count matrix, highlighting key decision points.

Normalization and Quality Control

The raw count matrix cannot be compared directly between samples due to technical variations like sequencing depth and RNA composition [10]. Normalization is essential.

Common Normalization Methods for Downstream Analysis:

| Method | Package | Principle | Best Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2's Median of Ratios [2] [10] | DESeq2 | Estimates size factors based on the median ratio of counts to a per-gene geometric mean. | Differential expression analysis between samples. |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) [2] [10] | edgeR | Uses a weighted trimmed mean of log-expression ratios to estimate scaling factors. | Differential expression analysis between samples. |

| TPM [9] [10] | Various | Transcripts Per Kilobase Million. Accounts for gene length and sequencing depth. | Within-sample gene expression comparisons. |

| FPKM/RPKM [9] [10] | Various | Similar to TPM but with a different calculation order. Not recommended for between-sample comparisons. | Legacy data; use TPM instead. |

Post-alignment Quality Control (QC) is critical. Tools like RSeQC and Picard Tools can evaluate sequencing saturation, coverage uniformity, and strand specificity [6]. Sample-level QC is performed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering on normalized, log-transformed counts to identify batch effects, outliers, and overall data structure [10] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enriches for mRNA by binding the poly-A tail, reducing ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination [5] [3]. |

| Ribo-depletion Kits | Selectively removes rRNA from total RNA, preserving both coding and non-coding RNA species [5] [3]. |

| Library Prep Kit (e.g., Illumina Stranded) | Provides all reagents for cDNA fragmentation, end-repair, dA-tailing, and adapter ligation in a single, optimized system [5]. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Ensures RNA samples are completely free of genomic DNA contamination prior to library preparation [4]. |

| Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Assesses RNA Integrity Number (RIN) to confirm input RNA quality and checks final library size distribution [4] [1]. |

| Size Selection Beads (e.g., SPRI) | Performs clean-up and size selection of cDNA fragments to ensure libraries contain inserts of the desired length [3]. |

| CCT373566 | CCT373566, MF:C26H29ClF2N6O3, MW:547.0 g/mol |

| (R)-Tco4-peg7-NH2 | (R)-Tco4-peg7-NH2, MF:C25H48N2O9, MW:520.7 g/mol |

The path from cDNA to a count matrix is a multi-stage process laden with critical choices that define the scope and resolution of an RNA-seq study. The selection between alignment-based and pseudoalignment-based quantification, coupled with the appropriate normalization strategy, tailors the analysis to the research objective, whether it is novel transcript discovery or rapid candidate gene screening. By adhering to rigorous QC protocols and understanding the tools and reagents involved, researchers can generate a high-quality count matrix—a robust foundation for identifying differentially expressed genes with confidence in drug development and basic research.

The reliability of conclusions drawn from RNA-seq data, especially in differential expression (DE) studies for identifying candidate genes, is not a matter of chance but a direct consequence of rigorous experimental design. Flawed designs can lead to wasted resources, irreproducible results, and misleading biological interpretations. This document outlines critical considerations for researchers designing RNA-seq experiments, focusing on three pillars of robust design: biological replication, optimal sequencing depth, and the mitigation of batch effects. The primary goal is to provide actionable protocols and evidence-based guidelines to ensure that your RNA-seq data is both powerful and trustworthy for downstream differential expression analysis.

The Critical Role of Biological Replication

Biological vs. Technical Replicates

A fundamental decision in any experimental design is the type of replication to use. In RNA-seq, the distinction is critical:

- Biological Replicates are measurements derived from distinct biological samples (e.g., different animals, individual plants, or independently cultured cell lines) representing the same condition. They are essential for capturing the natural biological variation within a population, which is necessary for making generalizable statistical inferences about the condition being studied [11].

- Technical Replicates are repeated measurements of the same biological sample. While they were once important for measuring technical noise in microarray experiments, in modern RNA-seq, technical variation is considerably lower than biological variation. Consequently, technical replicates are generally unnecessary and do not increase the power to detect biologically relevant differential expression [11] [12].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between replication, sequencing depth, and the resulting statistical power in an experimental design.

Determining the Number of Biological Replicates

The number of biological replicates is the most critical factor for the statistical power of a DE study. While more replicates are always beneficial, practical constraints require informed choices. Evidence from highly replicated studies provides clear guidance.

Table 1: Recommended Biological Replicates Based on Experimental Goals

| Experimental Goal | Minimum Recommended Replicates | Rationale and Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| General Gene-level DE | 4-6 replicates per condition | With 3 replicates, tools detect only 20-40% of DE genes; 6 replicates significantly improve power and FDR control [13]. |

| Detecting all DE genes (any fold-change) | 12 or more replicates per condition | To detect >85% of all significantly DE genes, including those with small fold-changes, more than 20 replicates may be needed [13]. |

| Detecting large-fold-change DE genes | 3-5 replicates per condition | For DE genes changing by more than fourfold, 3-5 replicates can identify >85% of them [13]. |

The data clearly shows that investing in biological replicates yields a greater return in statistical power than investing in deeper sequencing. A landmark study demonstrated that adding more biological replicates improves power significantly regardless of sequencing depth, whereas increasing sequencing depth beyond 10 million reads per sample gives diminishing returns [12]. For example, moving from two to three replicates at 10 million reads increased the number of detected DE genes by 35%, while tripling the reads per sample for two replicates yielded only a 27% increase [12].

Optimizing Sequencing Depth

Sequencing Depth Guidelines

Sequencing depth refers to the number of reads sequenced per sample. While deeper sequencing can improve the detection of lowly expressed transcripts, it must be balanced against the cost of sequencing and the greater benefit of additional replicates.

Table 2: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different RNA-seq Applications

| Application / Analysis Goal | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| General Gene-level Differential Expression | 15-30 million single-end (SE) reads per sample [11] [14]. | 15 million reads is often sufficient with >3 replicates. ENCODE guidelines suggest 30 million SE reads [11]. |

| Detection of Lowly Expressed Genes | 30-60 million reads per sample [11]. | Deeper sequencing helps quantify genes with low expression levels. |

| Isoform-level Differential Expression (Known isoforms) | At least 30 million paired-end (PE) reads [11]. | Paired-end reads are required to map exon junctions effectively. |

| Isoform-level Differential Expression (Novel isoforms) | >60 million PE reads [11]. | Longer read lengths are beneficial for spanning junctions. |

| Toxicogenomics / Dose-Response Studies | 20-40 million reads [15]. | Key toxicity pathways can be reliably detected even at modest depths; replication is more critical. |

Protocol: Experimental Design and Power Analysis

- Define Primary Objective: Clearly state the goal of your experiment (e.g., general DE, isoform discovery, detection of low-abundance transcripts).

- Prioritize Replicates: Allocate your budget to maximize the number of biological replicates. A minimum of 4 replicates per condition is strongly recommended, with 6 or more being ideal for robust DE analysis [13].

- Select Sequencing Depth: Based on your primary objective, select an appropriate sequencing depth using Table 2 as a guide. When in doubt, err on the side of more replicates with moderate depth (e.g., 20-30 million PE reads) rather than fewer replicates with ultra-deep sequencing.

- Consult a Statistician/Bioinformatician: If possible, perform a formal power analysis prior to the experiment. Tools like

PROPER(for RNA-seq power analysis in R) can help determine the optimal replicate number and depth for your expected effect size and biological variation.

Understanding and Mitigating Batch Effects

Defining and Identifying Batch Effects

Batch effects are technical sources of variation introduced during the experimental process that are unrelated to the biological question. They can arise from differences in reagent lots, personnel, day of processing, or even sequencing platform [16] [17]. If not controlled for, batch effects can increase variability, reduce statistical power, and, in the worst cases, create false associations or obscure true biological signals, leading to incorrect conclusions [16].

To determine if you have batches in your experiment, ask yourself the following questions [11]:

- Were all RNA isolations performed on the same day?

- Were all library preparations performed on the same day?

- Did the same person perform the RNA isolation/library prep for all samples?

- Did you use the same reagents (e.g., same lot number) for all samples?

- Were all samples sequenced on the same lane/flow cell/sequencing platform?

If the answer to any of these questions is "No," then you have batches.

Best Practices for Avoiding and Managing Batch Effects

The following workflow provides a strategic approach to managing batch effects throughout your experiment.

1. During Study Design: Avoid Confounding and Balance Batches The most effective way to handle batch effects is to design your experiment to avoid confounding. Confounding occurs when the effect of a batch is indistinguishable from the effect of your biological variable of interest. For example, if all control samples are processed in one batch and all treatment samples in another, the technical variation between batches is perfectly confounded with the treatment effect, making it impossible to separate the two [11].

- Best Practice: Ensure that samples from all experimental conditions are evenly distributed across all anticipated batches [11] [14]. If you have two treatment groups and must process samples in four batches, each batch should contain samples from both groups. This is a form of blocking that allows the statistical model to later separate the batch effect from the biological effect of interest.

2. During Sample Processing: Standardize and Randomize

- Standardize Protocols: Use the same protocols, reagents (preferably from the same lot), and personnel for all samples whenever possible.

- Randomize Processing Order: If samples cannot be processed simultaneously, randomize the order of processing across experimental conditions to avoid confounding with time.

3. During Metadata Collection: Document Everything Meticulously record all technical and procedural information. This metadata is essential for diagnosing and correcting for batch effects during analysis.

- Essential Metadata to Record: Date of RNA extraction, date of library prep, researcher who performed each step, reagent lot numbers, sequencing lane/flow cell ID, and sequencing platform.

4. During Data Analysis: Include Batch as a Covariate If you have designed your experiment to avoid confounding (i.e., batches are balanced across conditions), you can account for the technical variation during statistical testing.

- Protocol for DESeq2: In your statistical model, you can include

batchas a factor in the design formula. For example, if you have one primary condition and one batch effect, the design formula in DESeq2 would be:~ batch + condition[17]. This model will estimate the effect of the batch and remove it, allowing you to test for the effect of the condition while controlling for the batch.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function / Purpose | Considerations for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality, intact RNA from biological samples. | Use the same kit and, ideally, the same reagent lot for all samples to minimize batch effects. Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN); a RIN > 8 is often recommended for mRNA-seq [14]. |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries from RNA samples. | Stranded kits are recommended for accurate transcript assignment. Consistent use of kit and lot number is critical. |

| RNA Spike-in Controls | Exogenous RNA added to samples in known quantities. | Can be used to monitor technical variation and normalize for library preparation efficiency. Useful in specialized applications. |

| Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) | A standardized reference sample. | Can be included as a control across batches or labs to assess technical reproducibility and cross-study consistency. |

| Barcodes/Indexes | Short DNA sequences ligated to samples during library prep. | Allow for multiplexing—pooling multiple samples in a single sequencing lane. Ensure barcodes are balanced across conditions and batches. |

| High-Sensitivity DNA Assay Kit | Quantify the final library concentration accurately. | Essential for pooling libraries at equimolar concentrations to ensure even sequencing depth across samples. |

| GW461484A | GW461484A, MF:C19H15ClFN3, MW:339.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Thidiazuron-D5 | Thidiazuron-D5, MF:C9H8N4OS, MW:225.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Designing a robust RNA-seq experiment for differential expression requires careful forethought. The evidence overwhelmingly shows that biological replication is the cornerstone of a powerful study, providing greater returns on investment than ultra-deep sequencing. Furthermore, a vigilant approach to batch effects—through balanced experimental design, meticulous metadata tracking, and appropriate statistical correction—is non-negotiable for ensuring the validity and reproducibility of your findings. By adhering to the protocols and guidelines outlined in this document, researchers can generate high-quality, reliable data capable of uncovering meaningful biological insights in candidate gene research and beyond.

In differential gene expression research, the journey from raw sequencing output to biological insight relies on a structured pathway of data formats. Each format represents a stage of data reduction and refinement, transforming billions of raw sequence reads into a concise matrix of gene expression counts suitable for statistical analysis. This application note details the three cornerstone file formats—FASTQ, BAM, and count tables—that form the essential pipeline for RNA-seq studies aiming to identify candidate genes. Understanding the structure, generation, and interplay of these formats is fundamental for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals conducting robust, reproducible transcriptomic analyses.

The FASTQ Format: Raw Sequence Data

Format Specification and Contents

The FASTQ format is the primary output of high-throughput sequencing instruments and serves as the fundamental starting point for RNA-seq analysis. This text-based format stores both the nucleotide sequences and their corresponding quality scores in a single file [18]. Each sequencing read in a FASTQ file comprises four lines, as detailed below:

- Line 1 - Sequence Identifier: Begins with a '@' character followed by a unique instrument-specific identifier and metadata about the read's origin [19] [18].

- Line 2 - Raw Sequence Letters: The actual base calls (A, C, T, G, N) representing the sequenced fragment [19].

- Line 3 - Separator: A '+' character, optionally followed by the same sequence identifier [18].

- Line 4 - Quality Scores: Encoded quality values for each base in Line 2, using Phred+33 ASCII character representation [19].

A key feature of Illumina sequencing is paired-end reading, which generates two separate FASTQ files (R1 and R2) for each sample, representing both ends of each cDNA fragment [19] [20]. This approach provides more comprehensive sequencing coverage compared to single-read approaches.

Quality Encoding and Interpretation

The quality scores in FASTQ files are encoded using Phred scoring, which represents the probability of an incorrect base call. The formula Q = -10 × log10(P), where P is the probability of an error, translates to the following quality value interpretations [18] [20]:

Table: Quality Score Interpretation in FASTQ Files

| Phred Quality Score | Error Probability | Base Call Accuracy | Typical ASCII Character Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 in 10 | 90% | : (58) to ? (63) |

| 20 | 1 in 100 | 99% | 5 (53) to F (70) |

| 30 | 1 in 1000 | 99.9% | ? (63) to ^ (94) |

| 40 | 1 in 10000 | 99.99% | I (73) to ~ (126) |

These quality scores follow a specific ASCII encoding order, starting with '!' (lowest quality, value 0) to '~' (highest quality, value 93) [18]. Modern Illumina pipelines typically use #NNNNNN for the multiplex ID index sequence, providing sample-specific barcoding for pooled sequencing runs [18].

FASTQ Generation and Quality Assessment Protocol

Materials Required:

- Raw sequencing data in BCL (Binary Call) format from Illumina sequencer

- bcl2fastq conversion software (Illumina)

- Computing infrastructure with adequate storage

- FASTQC application for quality metrics (Babraham Institute)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

BCL to FASTQ Conversion: After sequencing completes, the instrument's Real-Time Analysis (RTA) software outputs raw base calls in BCL files. Convert these to FASTQ format using bcl2fastq conversion software [19].

Demultiplexing (if required): For multiplexed samples, the software assigns each sequence to its original sample based on the index (barcode) sequence, generating separate FASTQ files for each sample [19].

File Organization: A single-read run produces one FASTQ file (R1) per sample per lane, while a paired-end run produces two files (R1 and R2) per sample per lane. Files are typically compressed with the extension

.fastq.gz[19].Quality Assessment: Run FASTQC on all FASTQ files to generate comprehensive quality metrics:

This generates HTML reports containing per-base quality plots, sequence duplication levels, adapter contamination, and other essential metrics [20].

Basic Statistics Extraction: Use tools like

seqkit statsto obtain basic file statistics:This command returns the number of sequences, sum of sequence lengths, and average length for each FASTQ file [20].

Figure 1: FASTQ file generation and quality control workflow.

The BAM Format: Aligned Sequence Data

Format Specification and Conversion

BAM (Binary Alignment Map) files represent the compressed binary version of SAM (Sequence Alignment/Map) files and serve as the standard format for storing aligned sequencing reads [21] [22]. This format efficiently handles the massive data volumes typical in RNA-seq experiments while enabling rapid access and querying through indexing.

Key structural components of BAM files include:

- Header Section: Contains metadata about the entire file, including sample information, reference sequence details, and alignment method parameters [21] [22].

- Alignment Section: Contains the actual sequence alignments, with each record including the read name, sequence, quality scores, alignment position, mapping quality, and custom tags [21].

BAM files are generated through alignment of FASTQ files to a reference genome or transcriptome using alignment tools such as HISAT2, STAR, or Bowtie2. The binary format is significantly more storage-efficient than its text-based SAM counterpart—for example, a 321MB SAM file compresses to just 67MB in BAM format [23].

Essential Alignment Tags and Information

BAM files contain numerous tags that encode critical information about each alignment, with several being particularly relevant for RNA-seq analysis:

Table: Key Alignment Tags in BAM Files for RNA-Seq Analysis

| Tag | Full Name | Description | Importance in RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| RG | Read Group | Identifies the sample/library for the read | Essential for multiplexed samples; links reads to experimental conditions |

| BC | Barcode Tag | Records the demultiplexed sample ID | Ensures proper sample tracking in pooled sequencing |

| NM | Edit Distance | Records the Levenshtein distance between read and reference | Quantifies alignment quality and sequence variation |

| AS | Alignment Score | Paired-end alignment quality | Indicates confidence in fragment alignment |

| XS | Strandness | Indicates transcription strand | Crucial for strand-specific RNA-seq protocols |

BAM File Processing and Manipulation Protocol

Materials Required:

- SAMtools software package

- Reference genome sequence (FASTA format)

- Reference genome annotation (GTF/GFF format)

- Alignment software (HISAT2, STAR, etc.)

- Computing infrastructure with adequate memory

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Software Installation: Install SAMtools using Conda for easiest deployment:

Sequence Alignment: Align FASTQ files to reference using an appropriate aligner. For example, with HISAT2:

SAM to BAM Conversion: Convert the text-based SAM output to compressed BAM format:

BAM File Sorting: Sort the BAM file by genomic coordinates, required for downstream analysis and indexing:

BAM Indexing: Generate an index file (.bai) for rapid random access to the sorted BAM:

Quality Assessment: Generate alignment statistics using SAMtools:

Figure 2: BAM file generation and processing workflow.

The Count Table Format: Gene Expression Matrix

Format Specification and Content

The count table represents the final data reduction step in RNA-seq processing, transforming aligned reads into a numerical matrix of gene expression counts suitable for statistical analysis. This tab-delimited text file contains raw or normalized counts where rows correspond to genes and columns correspond to samples [9] [24].

The NCBI RNA-seq pipeline generates two primary types of count matrices [9]:

- Raw Counts Matrix: Contains unnormalized counts suitable for differential expression tools like DESeq2 and edgeR. The first column contains unique Gene IDs, with subsequent columns containing raw counts for each sample.

- Normalized Counts Matrix: Contains counts normalized according to sequencing depth and gene length, including:

- FPKM: Fragments Per Kilobase Million (paired-end) or Reads Per Kilobase Million (single-end)

- TPM: Transcripts Per Kilobase Million, often preferred for cross-sample comparisons

Count Distribution and Statistical Considerations

RNA-seq count data exhibits specific distribution characteristics that directly influence the choice of statistical models for differential expression analysis [24]:

- Zero Inflation: A large proportion of genes (often >20,000) have zero counts across all samples, requiring careful filtering [24].

- Mean-Variance Relationship: Unlike Poisson distribution assumptions (mean = variance), RNA-seq data consistently shows mean < variance, making the Negative Binomial distribution more appropriate for modeling [24].

- Long Right Tail: The data lacks an upper expression limit, resulting in a long right tail with highly expressed genes dominating the total count distribution.

Count Table Generation Protocol

Materials Required:

- Sorted BAM files from alignment step

- Genome annotation file (GTF/GFF format)

- Quantification software (featureCounts, HTSeq-count, or Salmon)

- R statistical environment with tximport package

- Computing infrastructure with adequate storage

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Read Quantification with featureCounts: Assign aligned reads to genomic features using featureCounts (from Subread package):

This command counts reads falling into exons and aggregates them by gene_id.

Alternative: Pseudoalignment with Salmon: For transcript-level quantification that doesn't require pre-alignment:

Transcript to Gene Summarization: When using transcript-level quantifiers, summarize to gene level using tximport in R:

Data Filtering: Remove lowly expressed genes to reduce noise in downstream analysis:

Normalization: Apply normalization to adjust for technical variations:

Figure 3: Count table generation and processing workflow.

Integrated RNA-Seq Workflow for Differential Expression

End-to-End Experimental Protocol

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-Seq Analysis

| Category | Specific Item/Reagent | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina Sequencing Kits (NovaSeq, NextSeq) | Cluster generation and sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry |

| Library Preparation | Poly(A) Selection Kits, rRNA Depletion Kits | mRNA enrichment from total RNA |

| Reference Materials | Reference Genomes (GRCh38, GRCm39) | Sequence alignment template |

| Gene Annotation (GENCODE, RefSeq) | Gene model definitions for quantification | |

| Software Tools | bcl2fastq (Illumina) | Base call to FASTQ conversion |

| HISAT2, STAR | Sequence alignment to reference | |

| SAMtools | BAM file processing and manipulation | |

| featureCounts, HTSeq-count | Read quantification per gene | |

| DESeq2, edgeR, limma | Differential expression analysis |

Comprehensive Experimental Workflow:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Extract high-quality total RNA from biological samples

- Perform poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion to enrich for mRNA

- Prepare sequencing libraries with appropriate barcodes for multiplexing

- Sequence on Illumina platform to generate BCL files

Primary Data Analysis:

- Convert BCL to FASTQ using bcl2fastq with demultiplexing

- Perform quality control with FASTQC

- Trim adapters and low-quality bases if necessary

Alignment and Processing:

- Align reads to reference genome/transcriptome using HISAT2 or STAR

- Convert SAM to BAM, sort, and index using SAMtools

- Assess alignment quality with flagstat and idxstats

Quantification:

- Generate raw count matrix using featureCounts or similar tool

- Alternatively, use pseudoalignment with Salmon followed by tximport

- Filter lowly expressed genes (e.g., keep genes expressed in ≥80% of samples)

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Read count data into R and create DGEList object (edgeR)

- Normalize using TMM method

- Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA) to assess sample relationships

- Conduct statistical testing for differential expression using appropriate design matrix

- Interpret results with visualization (volcano plots, heatmaps)

Quality Control Checkpoints

Throughout the workflow, several quality metrics should be assessed [9] [20]:

- FASTQ Stage: Minimum 50% alignment rate for inclusion in NCBI pipeline; Q30 scores for base quality

- BAM Stage: Alignment rates >70-80%; proper pairing rates >90% for paired-end data

- Count Table Stage: Examination of count distributions; identification of sample outliers via PCA

The progression from FASTQ to BAM to count tables represents both a technical and conceptual refinement of RNA-seq data, with each format serving distinct purposes in the analytical pipeline. FASTQ files contain the raw sequence data and quality metrics, BAM files provide genomic context through alignment, and count tables deliver the numerical abstraction required for statistical testing of differential expression. Understanding the structure, generation, and proper handling of these three fundamental formats empowers researchers to conduct robust transcriptomic analyses, identify candidate genes with confidence, and generate biologically meaningful insights for drug development and basic research.

The Analytical Pipeline: A Step-by-Step Guide from Raw Data to Differential Expression

In candidate gene research, the integrity of downstream differential expression analysis is entirely dependent on the quality of the initial data. Quality control (QC) and read trimming are the critical first steps in any RNA-seq pipeline, serving as the primary defense against erroneous conclusions. The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is particularly apt here; flawed raw data will inevitably lead to flawed biological interpretations, no matter the sophistication of subsequent differential expression algorithms [25]. This protocol details the implementation of a robust QC workflow using FastQC for quality assessment, fastp for read trimming and filtering, and MultiQC for aggregate reporting, ensuring that data proceeding to alignment and quantification is of the highest possible quality for reliable candidate gene identification.

The consequences of inadequate QC are profound. Sequencing artifacts, adapter contamination, or poor-quality bases can masquerade as biological signal, leading to both false positives and false negatives in differential expression calls [26] [27]. For research focused on specific candidate genes, this noise can obscure true expression differences, wasting resources and potentially misdirecting experimental validation. By implementing the comprehensive QC strategies outlined below, researchers can confidently proceed to differential expression analysis with DESeq2 or similar tools, knowing their findings are built upon a solid foundation.

The quality control process for RNA-seq data is a sequential pipeline where the output of each tool informs the next step. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and the logical relationships between the primary tools and processes.

Essential QC Tools and Their Functions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Software Solutions

The following table details the core software tools required for implementing a robust RNA-seq QC pipeline, along with their specific functions in the context of candidate gene research.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Role in RNA-seq QC Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC [28] [29] [30] | Quality Assessment | Provides a modular set of analyses to assess raw sequence data quality, including per-base sequencing quality, adapter contamination, and GC content. |

| fastp [28] [29] | Read Trimming & Filtering | Performs rapid, all-in-one preprocessing: adapter trimming, quality filtering, and polyG trimming (for modern Illumina instruments). |

| MultiQC [28] [29] | Report Aggregation | Synthesizes results from multiple tools (FastQC, fastp, etc.) and samples into a single, interactive HTML report for comparative analysis. |

| Trimmomatic [29] [31] | Read Trimming (Alternative) | A flexible, widely-used alternative to fastp for trimming Illumina adapters and removing low-quality bases. |

| CAQK peptide | CAQK peptide, MF:C17H32N6O6S, MW:448.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| POPEth-d5 | POPEth-d5, MF:C39H78NO8P, MW:725.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Interpreting Key QC Metrics

Successful quality control requires not just running tools, but also correctly interpreting their output. The table below summarizes critical metrics from FastQC and fastp reports and their implications for your data's quality and your downstream differential expression analysis.

| QC Metric | Target/Interpretation | Impact on Differential Expression Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Per-base Sequence Quality (FastQC) | Phred scores > 30 (Q30) are ideal [29] [31]. A drop at the 3' end is common but may require trimming. | Low quality can cause misalignment, reducing accurate quantification of your candidate genes. |

| Adapter Content (FastQC) | Should be low or absent. If significant (>~5%), adapter trimming is crucial [27]. | Adapter sequences can prevent reads from aligning, artificially reducing expression counts. |

| Sequence Duplication Levels (FastQC) | High levels can indicate PCR bias. Note: This is expected for 3' sequencing protocols like QuantSeq [25]. | Over-estimation of duplication can incorrectly flag true, highly expressed candidate genes as technical artifacts. |

| GC Content (FastQC) | Should generally follow a normal distribution. Sharp peaks often indicate contamination. | Unusual distributions can suggest contaminants that confound inter-sample comparisons. |

| Surviving Reads (fastp Report) | The percentage of reads remaining after trimming. A very low yield (e.g., <70%) may indicate poor sample quality. | Low yield reduces statistical power, making it harder to detect differential expression, especially for low-abundance transcripts. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Quality Assessment with FastQC

This protocol provides the first diagnostic snapshot of your raw sequencing data, identifying issues like poor quality, adapter contamination, or overrepresented sequences before they compromise downstream analysis.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Environment Setup: Ensure FastQC is installed, for example via Conda:

conda install -c bioconda fastqc[28]. - Create Output Directory:

mkdir fastqc_raw_results - Run FastQC: Execute FastQC on all your raw FASTQ files. For paired-end data, run on both files. The

-toption specifies the number of threads for parallel processing, speeding up the analysis. For a single sample, specify the files directly [28] [30]: - Interpret Results: Open the generated HTML report(s). Check for "fail" or "warn" flags in key modules like Per base sequence quality, Adapter Content, and Per sequence quality scores. These will guide your trimming strategy in the next protocol.

Protocol 2: Read Trimming and Filtering with fastp

This protocol uses the diagnostic information from FastQC to clean the raw reads by removing technical sequences (adapters) and low-quality bases, thereby increasing the accuracy of subsequent alignment to the reference genome.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Install fastp: Install via Conda:

conda install -c bioconda fastp[28]. - Run fastp: The following command is for paired-end data. fastp will automatically detect and trim adapters, apply quality filtering, and generate a comprehensive HTML report. The

-lparameter sets the minimum length for a read to be kept after trimming. For single-end data, specify the adapter sequence directly for more reliable trimming [28]: - Verify Trimming: Re-run FastQC on the trimmed FASTQ files (

sample1_R1_trimmed.fastq.gz, etc.) to confirm improvements in quality and adapter content.

Protocol 3: Aggregated Reporting with MultiQC

After running multiple tools across all samples, MultiQC synthesizes the results into a single, interactive report. This is indispensable for identifying trends, batch effects, and outliers in larger studies, which is critical for ensuring balanced and unbiased comparisons in differential expression analysis.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Install MultiQC: Install via Conda:

conda install -c bioconda multiqc[28]. - Run MultiQC: Navigate to the directory containing all your analysis outputs (FastQC and fastp reports). MultiQC will automatically scan, parse, and combine the data.

- Review the Aggregate Report: Open the

multiqc_report.htmlfile. Use this report to:- Quickly compare sequencing quality across all samples.

- Verify the consistency of trimming efficiency via the fastp statistics.

- Identify any sample outliers that may need to be excluded from downstream analysis based on poor overall quality or low read count after trimming [29].

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Even with a standardized protocol, challenges can arise. The following table addresses common problems and provides evidence-based solutions to ensure data quality.

| Common Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Quality Scores at Read Ends | Common artifact of Illumina sequencing chemistry. | A "light" trim of the 3' end using fastp's quality filtering is often sufficient [31]. |

| High Adapter Content | DNA fragments shorter than the read length. | Use --detect_adapter_for_pe (for paired-end) or provide a specific adapter sequence to fastp [28]. |

| Abnormal GC Content Distribution | Can indicate microbial or other contamination. | Compare the distribution to what is expected for your organism. Investigate potential sources of contamination if the distribution is multimodal [27]. |

| High Sequence Duplication | Can be due to PCR over-amplification during library prep or true biological overexpression. | Interpret with caution. For standard RNA-seq, it can be an issue. For 3'-end protocols (e.g., QuantSeq), high duplication is expected and should not be filtered aggressively [25]. |

| Low Read Count After Trimming | Severely degraded RNA or heavily contaminated libraries. | Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN) from the wet-lab QC. If the starting material was poor, consider re-preparing libraries. |

Best Practice: Incorporate QC checkpoints throughout the entire RNA-seq pipeline, not just at the start. For example, use tools like Qualimap after alignment to the reference genome to assess metrics like the distribution of reads across genomic features (exons, introns, intergenic regions), which can further validate library quality [28] [27] [32].

A rigorous quality control and trimming protocol is the cornerstone of reliable RNA-seq analysis. By systematically employing FastQC, fastp, and MultiQC, researchers can transform raw, noisy sequencing data into a clean, reliable dataset fit for purpose. In the context of candidate gene research, this initial effort directly translates to increased confidence in downstream differential expression results, ensuring that identified genes are true biological candidates and not artifacts of a flawed analytical foundation. This disciplined approach provides the robust platform required for subsequent steps of alignment, quantification, and statistical testing, ultimately leading to biologically meaningful and reproducible insights.

In the context of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) for differential expression analysis, the steps of read alignment and quantification are foundational. These processes transform raw sequencing data into a gene count matrix, which serves as the input for statistical tests to identify candidate genes [33] [1]. The choice of tools directly impacts the accuracy, sensitivity, and computational efficiency of the entire study [34]. Researchers are primarily faced with a choice between two methodological approaches: splice-aware alignment to a reference genome (e.g., with STAR or HISAT2), followed by counting, or pseudoalignment/pseudo-mapping directly to a reference transcriptome (e.g., with Salmon or Kallisto) which simultaneously performs quantification [35] [36] [37].

This article provides a detailed comparison of these tools, supported by quantitative data and standardized protocols, to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal pipeline for robust differential gene expression analysis.

Tool Comparison: Fundamental Differences and Performance

Core Concepts and Classifications

The tools can be categorized based on their underlying methodology and primary output.

Table 1: Fundamental Classifications and Characteristics of RNA-seq Quantification Tools

| Tool | Primary Classification | Reference Type | Key Output | Handles Splice Junctions? | Isoform-Level Quantification? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [38] [35] | Splice-aware Aligner | Genome | Base-level alignments (BAM/SAM files) | Yes (Splice-aware) | No (requires downstream tool like RSEM) |

| HISAT2 [38] [39] | Splice-aware Aligner | Genome | Base-level alignments (BAM/SAM files) | Yes (Splice-aware) | No (requires downstream tool) |

| Kallisto [38] [35] [39] | Pseudoaligner (De Bruijn graph) | Transcriptome | Transcript abundance estimates | Implicitly, via transcriptome | Yes |

| Salmon [38] [35] [39] | Quasi-mapper / Pseudoaligner | Transcriptome | Transcript abundance estimates | Implicitly, via transcriptome | Yes |

- Traditional Aligners (STAR, HISAT2): Tools like STAR perform a full, base-by-base alignment of reads to a reference genome, identifying their precise genomic coordinates. This is a computationally intensive process but provides rich data for quality control and the detection of novel genomic features [35] [36]. HISAT2 uses a hierarchical indexing system for memory efficiency [38] [39]. Both require a separate counting step (e.g., with

featureCountsorHTSeq) to generate the gene-level count matrix [40] [39]. - Pseudoaligners (Kallisto, Salmon): These tools forgo precise base-level alignment. Instead, they determine the set of transcripts from which a read could have originated by matching

k-mersor using "quasi-mapping," without specifying the exact location within the transcript [38] [35] [36]. This approach is dramatically faster and less memory-intensive, and it directly outputs abundance estimates while naturally handling multi-mapping reads [35] [36]. A key limitation is their dependence on a pre-defined transcriptome; they cannot discover novel transcripts or splice variants not included in the reference [35].

Empirical Performance and Benchmarking Data

Independent studies have systematically compared the performance of these tools in terms of their correlation and their impact on differential expression (DE) results.

Table 2: Empirical Performance Comparison Based on Published Studies

| Comparison Metric | Findings | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Count Correlation | Kallisto vs. Salmon: R² > 0.99 (Counts), R² > 0.80 (Abundance). STAR/HISAT2 vs. others: High correlation (>0.97) but with higher variance for lowly expressed genes. | [38] [39] |

| DEG Overlap | Kallisto vs. Salmon: ~97-98% overlap in identified DEGs. STAR/HISAT2 vs. Pseudoaligners: ~92-94% overlap. Majority of discrepancies due to differences in adjusted p-values, not log2 fold changes. | [38] [39] |

| Computational Resources | Kallisto was found to be 2.6x faster and use up to 15x less RAM than STAR. Salmon and Kallisto are generally comparable in speed and are significantly faster than alignment-based workflows. | [35] [36] |

| Alignment Rate | STAR achieved 99.5% mapping rate for Col-0 A. thaliana accession. Performance can drop for polymorphic accessions (e.g., 98.1% for N14). | [38] |

A benchmark analysis of HISAT2, Salmon, and Kallisto on a checkpoint blockade-treated CT26 mouse model dataset revealed that while all three methods showed a high correlation in the log2 fold changes of commonly identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (R² > 0.95), their adjusted p-values varied more considerably (R² ~ 0.4 - 0.7) [39]. This suggests that the core biological signal is consistent, but the statistical confidence assigned to each gene can differ, leading to the ~200-300 genes that are uniquely identified as significant by one method over another [39].

Experimental Protocols

Below are detailed, step-by-step protocols for two common and robust pipelines: an alignment-based workflow using STAR and a pseudoalignment-based workflow using Salmon. These protocols assume prior quality control of raw FASTQ files using tools like FastQC and optional adapter trimming with Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [40] [34].

Protocol 1: Alignment-Based Quantification with STAR and featureCounts

This pipeline is recommended when comprehensive quality control from BAM files, detection of novel splice junctions, or discovery of unannotated genomic features is a priority [35] [36].

- Genome Indexing (Prerequisite): First, generate a genome index for STAR.

- Read Alignment: Map the sequencing reads from each sample to the reference genome.

This generates a sorted BAM file (

sample_Aligned.sortedByCoord.out.bam) containing the genomic alignments. - Gene-level Quantification: Generate the count matrix using

featureCountsfrom theRSubreadpackage. The-t exonand-g gene_idparameters specify to count reads overlapping exons and aggregate them by gene identifier [40] [39].

Protocol 2: Pseudoalignment-Based Quantification with Salmon

This pipeline is ideal for rapid, accurate quantification of gene expression when a high-quality transcriptome is available and the primary goal is differential expression analysis [35] [36] [37].

- Transcriptome Indexing (Prerequisite): Build a Salmon index from a transcriptome FASTA file.

- Quantification: Run Salmon directly on the raw FASTQ files for each sample.

The

-l Aflag allows Salmon to automatically infer the library type [36]. The--validateMappingsoption enables selective alignment, which improves accuracy [35]. - Generating the Gene-level Count Matrix: Salmon outputs transcript-level abundance estimates (in

quant.sffiles). To perform gene-level differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2, use thetximportR package to summarize transcript counts to the gene level and correct for potential length biases [36].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the two primary workflows for RNA-seq data analysis, from raw reads to a count matrix, highlighting the key differences between alignment-based and pseudoalignment-based approaches.

Differential Expression Analysis with DESeq2

The final gene count matrix from either protocol is analyzed for differential expression using statistical software like DESeq2. The core steps of the DESeq2 analysis pipeline are summarized below.

The DESeq() function is a wrapper that performs three key steps in sequence [37]:

- Normalization: Corrects for differences in sequencing depth and RNA composition between samples using the "median of ratios" method [37].

- Dispersion Estimation: Models the variance in gene expression as a function of the mean, accounting for overdispersion common in count data using a negative binomial model [37].

- Model Fitting and Testing: Fits a generalized linear model for each gene and tests for differential expression using the Wald test or likelihood ratio test [37].

Results are typically extracted by specifying the contrast of interest (e.g., treated vs. control), and genes are considered differentially expressed based on a user-defined threshold for the adjusted p-value (e.g., FDR < 0.05) and log2 fold change [40].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for RNA-seq Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | A sequence of the organism's DNA used as a map for alignment. | FASTA file (e.g., GRCm39 for mouse). Required for STAR/HISAT2. |

| Genome Annotation | File describing the locations of genes, transcripts, exons, and other features. | GTF or GFF file (e.g., from Ensembl). Critical for alignment and counting. |

| Reference Transcriptome | A collection of all known transcript sequences for an organism. | FASTA file. Mandatory for Salmon and Kallisto. |

| Stranded RNA Library Prep Kit | Determines whether the sequenced read originates from the sense or antisense strand. | Kits like Illumina's TruSeq Stranded Total RNA. Crucial for specifying library type during quantification [33] [36]. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kit | Enriches for non-ribosomal RNAs (mRNA, lncRNA) by removing abundant rRNA. | Kits like Ribo-Zero. Essential for studying non-polyadenylated RNAs [33]. |

| Poly(A) Selection Kit | Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by capturing the poly-A tail. | Standard for mRNA-seq. Not suitable for degraded RNA (e.g., from FFPE) [33]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the substantial computational power and memory required for data processing. | Necessary for running STAR on large datasets. Salmon/Kallisto can often be run on a powerful desktop [35] [36]. |

In the realm of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) for differential expression (DE) analysis, normalization is not merely a preliminary step but a foundational statistical requirement for ensuring data integrity. RNA-seq enables genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance, offering more comprehensive transcriptome coverage and finer resolution of dynamic expression changes compared to earlier methods like microarrays [41]. However, raw transcript counts derived from sequencing are influenced by technical variables including sequencing depth, gene length, and library composition [41] [42]. Without correction, these factors can obscure true biological signals and lead to the spurious identification of differentially expressed candidate genes, directly impacting the validity of downstream conclusions in drug development research [43] [44]. This guide details the core principles and practical applications of both standard and advanced normalization methods, providing a rigorous framework for their implementation in a research setting focused on differential expression.

The Necessity of Normalization in RNA-seq Analysis

Normalization adjusts raw transcriptomic data to account for technical factors that mask actual biological effects [42]. The primary sources of technical bias are:

- Sequencing Depth: Samples with a greater total number of sequenced reads (library size) will naturally have higher raw counts for a gene, even if its actual expression level is unchanged [41].

- Gene Length: For a given expression level, longer genes will generate more sequencing fragments than shorter ones. This is a critical factor when comparing expression levels between different genes within the same sample [42].

- RNA Composition: In certain conditions, a small number of genes may be extremely highly expressed in one sample. These genes consume a large fraction of the sequencing reads, skewing the count distribution and making the rest of the genes appear less expressed by comparison [41] [42]. This is a key challenge for cross-sample comparisons.

Failure to correct for these biases can result in false positives or false negatives during differential expression testing, misdirecting research efforts and potentially compromising biomarker discovery [44].

Within-Sample Normalization Methods

Within-sample normalization enables the comparison of expression levels between different genes within a single sample by accounting for sequencing depth and gene length [42]. However, these methods are generally not suitable for differential expression analysis across samples, as they do not adequately correct for composition effects [43] [45].

Table 1: Comparison of Within-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Stands For | Corrects for Sequencing Depth | Corrects for Gene Length | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Counts Per Million | Yes | No | Comparing the same gene across samples (when used with between-sample methods); not for DE [41] [45] [42]. |

| RPKM/FPKM | Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase Million | Yes | Yes | Comparing gene expression within a single sample; not recommended for cross-sample comparison or DE [46] [43] [42]. |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Kilobase Million | Yes | Yes | Comparing gene expression within a single sample; preferred over RPKM/FPKM for within-sample comparisons [46] [45] [42]. |

The calculation workflows for these methods are distinct. The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of operations for TPM and RPKM/FPKM, highlighting the key difference in order that makes TPM more reliable for within-sample analysis.

Figure 1. Workflow Comparison of TPM and RPKM/FPKM Calculations. The key difference lies in the order of operations: TPM normalizes for gene length first, then sequencing depth, resulting in consistent totals across samples. RPKM/FPKM performs these steps in reverse [46].

Protocol: Calculating TPM for a Single Sample

Purpose: To obtain normalized expression values suitable for comparing the relative abundance of different transcripts within a single RNA-seq sample.

Procedure:

- Input Raw Data: Begin with a vector of raw read counts mapped to each gene or transcript in the sample.

- Normalize for Gene Length: Divide each gene's raw read count by its length (in kilobases). This yields Reads Per Kilobase (RPK).

RPK_gene_i = (RawCount_gene_i) / (GeneLength_gene_i_kb)

- Calculate Scaling Factor: Sum all RPK values in the sample. Divide this sum by 1,000,000 to obtain a "per million" scaling factor.

ScalingFactor = (Sum_of_all_RPK) / 1,000,000

- Normalize for Sequencing Depth: Divide each RPK value by the scaling factor to obtain TPM.

Note: The sum of all TPM values in a sample will always be 1,000,000, allowing for direct comparison of the proportion of the transcriptome represented by each gene across different samples [46].

Between-Sample Normalization for Differential Expression

Differential expression analysis requires specialized between-sample normalization methods that are robust to library composition biases. These methods are embedded within established statistical packages for DE analysis and are the gold standard for identifying candidate genes [43] [44].

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Between-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Package/Algorithm | Key Assumption | Mechanism | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | edgeR [41] [44] | Most genes are not differentially expressed (DE) [42]. | Trims extreme fold-changes (M-values) and library sizes to compute a scaling factor relative to a reference sample [41] [42]. | Robust to unequal RNA compositions; highly effective for DE analysis [44] [45]. |

| Median-of-Ratios (RLE) | DESeq2 [41] [44] | Most genes are not DE. | Calculates a reference expression for each gene; the size factor for a sample is the median of the ratios of its counts to these references [41]. | Consistently performs well in benchmarks; robust for DE analysis [43] [44]. |

Protocol: Differential Expression Analysis with DESeq2

Purpose: To perform a rigorous differential expression analysis between two or more biological conditions using the DESeq2 package, which incorporates the median-of-ratios normalization method.

Procedure:

- Input Data Preparation:

- Count Matrix: A matrix of raw, non-normalized integer read counts. Rows represent genes and columns represent samples. Do not use FPKM, TPM, or other pre-normalized counts [47].

- Column Data: A data frame specifying the experimental design (e.g., ~ condition).

Create DESeqDataSet Object:

Perform Differential Analysis and Normalization: The

DESeq()function performs normalization (estimating size factors via the median-of-ratios method), model fitting, and hypothesis testing in a single step.Extract Normalized Counts (Optional): These can be used for visualization, but not for further DE analysis.

Extract Results: Obtain the table of differential expression statistics, including log2 fold changes and adjusted p-values.

Experimental Design Considerations:

- Biological Replicates: A minimum of three replicates per condition is standard. With only two replicates, the ability to estimate variability and control false discovery rates is greatly reduced [41].

- Sequencing Depth: For standard DGE analysis, ~20–30 million reads per sample is often sufficient [41].

The overall workflow for a differential expression analysis, from raw data to biological insight, integrates these normalization and analysis steps.

Figure 2. End-to-End Workflow for RNA-seq Differential Expression Analysis. The critical stage of between-sample normalization is performed by specialized tools like DESeq2 or edgeR as part of the differential expression analysis, using the raw count matrix as input [41] [47].

Table 3: Key Tools and Reagents for RNA-seq Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools/Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control & Trimming | Assesses raw read quality and removes adapter sequences/low-quality bases. | FastQC, multiQC, Trimmomatic, Cutadapt [41]. |

| Alignment Software | Maps sequenced reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 [41]. |

| Pseudoalignment Tools | Rapid quantification of transcript abundances without full alignment. | Kallisto, Salmon [41]. |

| Quantification Tools | Generates the raw count matrix summarizing reads per gene. | featureCounts, HTSeq-count [41]. |

| Differential Expression Packages | Performs statistical testing for DE, incorporating robust normalization. | DESeq2, edgeR, limma [41] [47]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes used in some protocols to correct for PCR amplification bias. | Common in droplet-based scRNA-seq protocols (e.g., Drop-Seq, inDrop) [48]. |

The choice of normalization method is a critical determinant of success in RNA-seq studies aimed at differential expression. For comparing gene expression within a single sample, TPM is the preferred metric. However, for the core task of identifying differentially expressed candidate genes across conditions, the advanced between-sample normalization methods embedded in DESeq2 (median-of-ratios) and edgeR (TMM) are the established and benchmarked gold standards [43] [44]. These methods are specifically designed to handle the technical variances of RNA-seq data, providing the statistical rigor required for robust biomarker discovery and downstream applications in drug development.

Differential expression (DE) analysis represents a fundamental step in understanding how genes respond to different biological conditions in RNA-seq experiments, playing a crucial role in candidate gene research and drug development [49]. When researchers perform RNA sequencing, they're essentially taking a snapshot of all the genes active in samples at a given moment, with the real biological insights emerging from understanding how these expression patterns change between conditions, time points, or disease states [49]. The power of DE analysis lies in its ability to identify these changes systematically across tens of thousands of genes simultaneously while accounting for biological variability and technical noise inherent in RNA-seq experiments [49]. For researchers investigating candidate genes, the selection of appropriate statistical tools is paramount, with DESeq2, edgeR, and limma emerging as the most widely-used tools for differential gene expression analysis of bulk transcriptomic data [50]. These tools address specific challenges in RNA-seq data including count data overdispersion, small sample sizes, complex experimental designs, and varying levels of biological and technical noise [49]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging these tools within the context of candidate gene research, offering detailed protocols, comparative analyses, and visualization strategies to enhance research reproducibility and biological insight generation.

Comparative Analysis of DE Tools

Statistical Foundations and Performance Characteristics

DESeq2, edgeR, and limma employ distinct statistical approaches for differential expression analysis, each with unique strengths for specific experimental conditions in candidate gene research. DESeq2 utilizes negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes, performing internal normalization based on geometric means [49]. EdgeR similarly employs negative binomial modeling but offers more flexible options for common, trended, or tagged dispersion estimation with TMM normalization by default [49]. In contrast, limma uses linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation and a voom transformation that converts counts to log-CPM values, improving variance estimates for small sample sizes [49].

Extensive benchmark studies have provided valuable insights into the relative strengths of these tools. A 2024 study evaluating robustness of differential gene expression analysis found that patterns of relative DGE model robustness proved dataset-agnostic and reliable for drawing conclusions when sample sizes were sufficiently large [51]. Overall, the non-parametric method NOISeq was the most robust followed by edgeR, voom, EBSeq and DESeq2 [51]. Another study comparing association analyses of continuous exposures found that linear regression methods (as used in limma) are substantially faster with better control of false detections than other methods [52].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma

| Aspect | limma | DESeq2 | edgeR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation |

| Data Transformation | voom transformation converts counts to log-CPM values | Internal normalization based on geometric mean | TMM normalization by default |

| Variance Handling | Empirical Bayes moderation improves variance estimates for small sample sizes | Adaptive shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes | Flexible options for common, trended, or tagged dispersion |

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates per condition | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples |

| Computational Efficiency | Very efficient, scales well | Can be computationally intensive | Highly efficient, fast processing |

| Best Use Cases | Small sample sizes, multi-factor experiments, time-series data | Moderate to large sample sizes, high biological variability, subtle expression changes | Very small sample sizes, large datasets, technical replicates |

Tool Selection Guidelines for Candidate Gene Research

For researchers focused on candidate gene analysis, tool selection should be guided by specific experimental parameters and research goals. Limma demonstrates remarkable versatility and robustness across diverse experimental conditions, particularly excelling in handling outliers that might skew results in other methods [49]. Its computational efficiency becomes especially apparent when processing large-scale datasets containing thousands of samples or genes, making it valuable for candidate gene validation across multiple sample cohorts [49]. However, limma's statistical framework relies on having sufficient data points to estimate variance reliably, which translates to a requirement of at least three biological replicates per experimental condition [49].

DESeq2 and edgeR share many performance characteristics, which isn't surprising given their common foundation in negative binomial modeling [49]. Both tools perform admirably in benchmark studies using both real experimental data and simulated datasets where true differential expression is known [49]. However, they do show subtle differences in their sweet spots – edgeR particularly shines when analyzing genes with low expression counts, where its flexible dispersion estimation can better capture the inherent variability in sparse count data [49]. This makes it particularly valuable for candidate genes that may be lowly expressed but biologically significant.

A 2024 comprehensive workflow for optimizing RNA-seq data analysis emphasized that different analytical tools demonstrate variations in performance when applied to different species, suggesting that researchers working with non-model organisms should consider tool performance specific to their experimental system [53]. For fungal pathogen studies, for example, the study found that edgeR and DESeq2 showed superior performance for differential expression analysis in plant pathogenic fungi [53].

Experimental Design and Setup

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA from biological samples | Ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8 for optimal results |

| Library Preparation Kits | Construction of sequencing libraries | Poly(A) selection for mRNA or rRNA depletion protocols |

| Alignment Software | Mapping reads to reference genome | HISAT2, STAR, TopHat [54] |

| Quantification Tools | Generating count matrices from aligned reads | featureCounts, HTSeq [54] |

| R/Bioconductor Packages | Differential expression analysis | DESeq2, edgeR, limma [49] [50] |

| Quality Control Tools | Assessing RNA-seq data quality | FastQC, Trimmomatic, fastp [53] [54] |

Sample Size Considerations and Experimental Design

Robust experimental design is crucial for reliable candidate gene detection in RNA-seq studies. For organism-specific studies, a 2024 comprehensive workflow for optimizing RNA-seq data analysis demonstrated that different analytical tools show variations in performance when applied to different species [53]. Their analysis of fungal RNA-seq datasets revealed that tool performance can vary significantly across species, highlighting the importance of species-specific optimization when investigating candidate genes in non-model organisms.

Regarding sample size, the required number of biological replicates depends on the effect size researchers aim to detect and the statistical power desired. While edgeR can technically work with as few as 2 replicates per condition, reliable detection of differentially expressed candidate genes typically requires at least 3-5 biological replicates per condition for adequate statistical power [49]. For candidate gene research where effect sizes may be subtle but biologically important, increasing replicate number is often more valuable than increasing sequencing depth.

For complex experimental designs involving multiple factors such as time series, drug doses, or genetic backgrounds, limma provides particularly flexible modeling capabilities [49]. Its ability to handle complex designs elegantly makes it well-suited for sophisticated candidate gene studies that go beyond simple two-group comparisons [49].

Detailed Protocols

Comprehensive RNA-seq Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete RNA-seq differential expression analysis workflow, from raw data to biological interpretation:

DESeq2 Analysis Protocol

The DESeq2 package provides a comprehensive pipeline for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. The following protocol assumes availability of a count matrix and sample metadata table:

Step 1: Data Preparation and DESeqDataSet Creation

Step 2: Differential Expression Analysis

edgeR Analysis Protocol

EdgeR provides robust differential expression analysis, particularly effective for studies with limited replicates:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Normalization

Step 2: Differential Expression Testing

limma Analysis Protocol

Limma with voom transformation is particularly effective for complex experimental designs:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Voom Transformation

Results Visualization and Interpretation

Comparative Result Analysis

After running individual analyses with DESeq2, edgeR, and limma, researchers should compare results across methods to identify robust candidate genes:

Visualization of Method Concordance

The relationship between the three differential expression methods and their shared results can be visualized as follows:

Advanced Visualization Techniques

For comprehensive result interpretation, researchers should employ multiple visualization approaches:

Volcano Plot Implementation:

For candidate gene research using RNA-seq technology, robust differential expression analysis requires careful tool selection and methodological rigor. DESeq2, edgeR, and limma each offer distinct advantages depending on experimental design, sample size, and biological question [49]. The high concordance observed between these methods when applied to well-powered studies strengthens confidence in candidate genes identified by multiple approaches [49] [50].

Best practices for candidate gene research include: (1) utilizing at least two differential expression methods to identify high-confidence candidates; (2) employing appropriate multiple testing correction with FDR control at 5%; (3) applying biologically relevant fold-change thresholds in addition to statistical significance; (4) validating key findings using orthogonal methods such as qRT-PCR; and (5) considering species-specific performance characteristics when selecting analytical tools [53].

The implementation of standardized workflows using these established tools enhances reproducibility in candidate gene research and facilitates meta-analyses across studies. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and find applications in molecular diagnostics, rigorous methodological approaches for differential expression analysis remain fundamental to advancing our understanding of gene function in health and disease [51].

Navigating Challenges and Enhancing Analysis Accuracy

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, providing unprecedented resolution for differential gene expression (DGE) studies in basic research and drug development. However, the intricate workflow from sample preparation to data analysis introduces several technical challenges that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous biological interpretations. Library composition bias, over-trimming of reads, and ambiguous read mapping represent three critical pitfalls that directly impact the accuracy of candidate gene expression quantification. These technical artifacts can obscure genuine biological signals, introduce false positives in differential expression analysis, and ultimately misdirect therapeutic development efforts. This Application Note details the origins, consequences, and practical mitigation strategies for these challenges, providing researchers with validated protocols to enhance the reliability of their RNA-seq data within the context of differential expression research.

Understanding and Mitigating Library Composition Bias

Origins and Impact on Differential Expression

Library composition bias arises when differential representation of RNA species in sequencing libraries distorts the apparent abundance of transcripts. Unlike library size bias (which affects the total number of reads per sample), composition bias concerns the relative proportions of different transcripts within and between samples [55]. This bias fundamentally stems from the nature of RNA-seq data as a relative measurement—the count for a gene is proportional to its abundance divided by the total RNA abundance in the sample. Consequently, a massive upregulation of a few genes in one condition can artificially depress the counts for other, non-differentially expressed genes in the same sample, making them appear downregulated [55].

The core of the problem lies in normalization. Simple normalization methods like Counts Per Million (CPM) assume that the total RNA output between samples is equivalent and that most genes are not differentially expressed. However, in experiments with global transcriptional shifts, such as drug treatments or disease states, these assumptions break down. Table 1 summarizes the primary sources and consequences of this bias.

Table 1: Sources and Consequences of Library Composition Bias

| Source of Bias | Description | Impact on Differential Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme Differential Expression | A small subset of genes is vastly overexpressed in one condition, consuming a larger share of the sequencing "budget" [55]. | Non-DE genes in the same sample are artificially depressed, leading to false positives for downregulation. |

| Global Transcriptional Shifts | The total cellular RNA content differs significantly between experimental groups or cell types [56]. | Standard global scaling methods fail, distorting expression estimates for a large number of genes. |

| Protocol Selection | PCR amplification during library prep preferentially amplifies certain transcripts based on GC content or length [57]. | Introduces systematic technical variation that can be confounded with biological effects. |