Carrier Screening for Recessive Genetic Disorders: A 2025 Research and Clinical Implementation Review

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of carrier screening for recessive genetic disorders, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Carrier Screening for Recessive Genetic Disorders: A 2025 Research and Clinical Implementation Review

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of carrier screening for recessive genetic disorders, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles and evolving landscape, including the shift from targeted to expanded pan-ethnic screening. The review details current methodological applications of next-generation sequencing and the integration of AI in data analysis, while addressing key challenges in variant interpretation, panel design, and equitable access. It further examines validation frameworks through clinical utility studies and cost-effectiveness analyses, synthesizing evidence to inform future biomedical research, clinical practice, and therapeutic development.

The Evolving Landscape of Carrier Screening: From Ethnic-Specific Tests to Pan-Ethnic Panels

Carrier screening for recessive genetic disorders represents a cornerstone of modern preventive genetics, with its origins deeply rooted in the targeted detection of two distinct disease categories: Tay-Sachs disease and hemoglobinopathies. These pioneering screening programs established the fundamental paradigm of ethnicity-based risk assessment that dominated genetic screening for decades [1] [2]. The historical development of these screening initiatives reveals a fascinating interplay between scientific discovery, technological innovation, and evolving understanding of population genetics. This application note delineates the foundational principles, methodological evolution, and key experimental protocols that underpin these screening approaches, providing researchers and clinical scientists with essential technical frameworks for understanding carrier screening development within a broader research context on recessive genetic disorders.

The original carrier screening programs emerged in the 1970s with two primary targets: Tay-Sachs disease in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry and hemoglobinopathies (specifically sickle cell anemia and β-thalassemia) in specific ethnic populations [1]. These initiatives established the practice of targeting severe autosomal recessive disorders with elevated carrier frequencies in defined populations, creating an ethical and practical framework that would guide genetic screening for generations. The success of these early programs demonstrated that identifying asymptomatic heterozygotes could significantly reduce disease incidence through informed reproductive decision-making [2].

Historical Context and Epidemiological Foundations

Tay-Sachs Disease: From Clinical Description to Targeted Screening

The history of Tay-Sachs disease begins with clinical observations in the late 19th century. British ophthalmologist Warren Tay first described the characteristic cherry-red spot on the retina of a one-year-old patient in 1881, while New York neurologist Bernard Sachs subsequently detailed the cellular changes and heritability pattern, noting the higher occurrence in Jews of Eastern and Central European descent [3] [4]. These initial clinical observations established Tay-Sachs as a distinct neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive neuronal damage due to GM2 ganglioside accumulation [5].

The epidemiological understanding of Tay-Sachs disease evolved significantly throughout the 20th century. Initial characterizations treated it as an exclusively Jewish disorder, with the first edition of the Jewish Encyclopedia (1901-1906) describing it as "a rare and fatal disease of children, occurs mostly among Jews" [3]. By the 1930s, however, researcher David Slome concluded that Tay-Sachs disease followed an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern and was not exclusively a Jewish phenomenon, having found records of eighteen cases in Gentile families in the medical literature [3]. The carrier frequency in the general population is approximately 1 in 250, but rises to 1 in 27 among individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, with similarly elevated frequencies in certain other populations including French Canadians and Cajuns [5].

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Tay-Sachs Disease Understanding

| Time Period | Key Developments | Scientific Advances |

|---|---|---|

| 1881-1900 | Initial clinical descriptions by Tay and Sachs | Recognition of distinctive clinical features and familial pattern |

| 1901-1960 | Characterization as "Jewish disorder" | Understanding of autosomal recessive inheritance |

| 1969 | Discovery of enzymatic deficiency | Okada and O'Brien identify hexosaminidase A deficiency |

| 1970s | First targeted screening programs | Development of enzyme assay testing for carriers |

Hemoglobinopathies: Global Distribution and Selective Advantage

Hemoglobinopathies, comprising thalassemias and structural hemoglobin variants, represent the most common monogenic disorders worldwide, with an estimated 4.5% of the global population carrying a gene for thalassemia or hemoglobin anomaly [6]. The original geographic distribution of these disorders closely aligned with malaria-endemic regions, from Africa through the Mediterranean basin to Southeast Asia, providing compelling evidence for natural selection favoring carriers due to resistance to Plasmodium falciparum malaria [7]. This selective advantage created dramatically different carrier frequencies across populations, from 1-5% in non-endemic regions to 5-30% in endemic areas [6].

The historical understanding of hemoglobinopathies advanced significantly through protein chemistry and biochemical techniques. Linus Pauling's seminal 1949 description of sickle cell hemoglobin as a "molecular disease" established the fundamental concept that genetic mutations could cause structural protein alterations [8]. Subsequent research elucidated the genetic complexity of hemoglobin disorders, including the dual-gene cluster arrangement (α-globin genes on chromosome 16, β-globin genes on chromosome 11) and developmental regulation of hemoglobin switching from embryonic to fetal to adult forms [7] [8].

Table 2: Epidemiological Distribution of Key Hemoglobinopathies

| Disorder | High-Prevalence Populations | Carrier Frequency | Primary Genetic Defect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Disease | Sub-Saharan Africa, India, Middle East | 1 in 10 (African Americans) [9] | HbS structural variant (Glu6Val in β-globin) |

| β-Thalassemia | Mediterranean, Middle East, Southeast Asia | 1-20% (varies by region) [7] | Reduced or absent β-globin synthesis |

| α-Thalassemia | Southeast Asia, African, Mediterranean | 1 in 20 (Asians) [9] | Reduced or absent α-globin synthesis |

| HbE/β-thalassemia | Southeast Asia, parts of India | Varies regionally [7] | Structural variant combined with thalassemia |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Evolution

Tay-Sachs Disease Screening: From Enzyme Assays to DNA Analysis

The original Tay-Sachs carrier screening protocol relied exclusively on enzymatic measurement, a methodology made possible by the 1969 discovery by Okada and O'Brien that Tay-Sachs disease resulted from deficiency of the enzyme hexosaminidase A (Hex A) [3] [4]. The standard enzyme assay protocol involves:

Specimen Collection and Preparation:

- Collect 5-10 mL venous blood in EDTA or heparinized tubes

- Separate leukocytes from peripheral blood samples via density gradient centrifugation

- Alternatively, use serum for initial screening with follow-up leukocyte testing for confirmation

- Store samples at 4°C and process within 24-48 hours

Hexosaminidase A Activity Measurement:

- Lyse leukocytes using detergent-based lysis buffer (0.2% Triton X-100)

- Incubate lysate with synthetic fluorogenic substrate (typically 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfate)

- For differential measurement, perform parallel incubations with and without heat inactivation (50°C for 3 hours) as Hex B is heat-stable while Hex A is heat-labile

- Stop reaction with alkaline buffer (glycine, pH 10.5)

- Measure fluorescence (excitation 365 nm, emission 450 nm)

Calculation and Interpretation:

- Calculate Hex A activity as percentage of total hexosaminidase activity

- Carrier range: 40-60% of normal Hex A activity

- Affected individuals: <1% of normal Hex A activity

- Intermediate values may indicate juvenile-onset variants or pseudodeficiency alleles [3] [4] [5]

With advances in molecular genetics, DNA-based testing has supplemented enzymatic screening, particularly for identification of specific mutations common in Ashkenazi Jewish populations. The current recommended protocol includes:

DNA Extraction and Amplification:

- Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes using standardized kits

- Amplify HEXA gene regions containing common mutations via PCR

- Common mutations targeted include 1278insTATC, IVS12+1G>C, and G269S

Mutation Detection:

- Utilize restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis for known mutations

- Implement allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization or real-time PCR with specific fluorescent probes

- For comprehensive analysis, employ next-generation sequencing of entire HEXA coding region, splice junctions, and promoter regions [2] [5]

Hemoglobinopathy Screening: Integrated Hematological and Biochemical Approaches

Carrier screening for hemoglobinopathies requires an integrated methodological approach combining multiple techniques to detect both structural variants and thalassemia syndromes. The standard workflow progresses from basic hematological parameters to specialized protein and molecular analyses:

Primary Hematological Assessment:

- Complete blood count with emphasis on erythrocyte indices:

- Microcytosis: MCV < 80 fL

- Hypochromia: MCH < 27 pg

- Peripheral blood smear examination for:

- Anisopoikilocytosis, target cells, basophilic stippling

- Sickled forms (in sickle cell disorders)

- Heinz bodies (in unstable hemoglobin variants)

- Reticulocyte count to assess erythropoietic response

Hemoglobin Separation and Quantification:

- Cellulose acetate electrophoresis (pH 8.6) for initial screening

- Citrate agar electrophoresis (pH 6.2) for confirmation of specific variants

- Quantitative hemoglobin analysis via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC):

- Use cation-exchange HPLC with gradient elution

- Quantify HbA, HbA2, HbF, and variant hemoglobins

- Elevated HbA2 (>3.5%) diagnostic for β-thalassemia trait

- Alternative method: capillary electrophoresis for high-resolution separation [7] [8] [6]

Supplementary Biochemical Tests:

- Sickling test: metabolically-induced sickling with sodium metabisulfite

- HbF quantification via alkali denaturation method or flow cytometry

- Stability tests for unstable hemoglobins (isopropanol or heat stability)

- Oxygen affinity measurements for variants with altered oxygen binding [8] [6]

Molecular Genetic Analysis:

- DNA extraction from peripheral blood leukocytes

- α-globin and β-globin gene analysis via PCR-based methods:

- Gap-PCR for common deletion mutations (e.g., α-thalassemia deletions)

- Reverse dot-blot hybridization or array analysis for common point mutations

- DNA sequencing for rare or novel mutations

- Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) for detection of deletions/duplications [7] [6]

Technological Evolution and Research Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Carrier Screening Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Substrates | 4-Methylumbelliferyl-β-D-N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfate | Tay-Sachs enzyme assays | Fluorogenic substrate for Hex A activity measurement |

| Chromatography Media | DEAE-Sephadex, Cation-exchange resins | Hemoglobin separation | Separation of hemoglobin variants based on charge differences |

| Electrophoresis Systems | Cellulose acetate membranes, Citrate agar gels, Isoelectric focusing gels | Hemoglobin variant screening | Separation of hemoglobin types based on electrophoretic mobility |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | PCR primers for HEXA, HBB, HBA genes; Restriction enzymes; DNA sequencing kits | Mutation detection | Amplification and analysis of specific gene mutations |

| Antibodies | Anti-Hex A antibodies, Anti-hemoglobin type-specific antibodies | Protein quantification and localization | Immunoassays and immunohistochemical detection |

| Siponimod-D11 | Siponimod-D11, MF:C29H35F3N2O3, MW:527.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Chlorzoxazone-13C,15N,D2 | Chlorzoxazone-13C,15N,D2, MF:C7H4ClNO2, MW:173.56 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Visualization of Historical Screening Workflow

Tay-Sachs Disease Molecular Pathway

Contemporary Applications and Research Implications

Transition to Expanded Pan-Ethnic Screening

The historical foundation of ethnicity-based screening has progressively evolved toward pan-ethnic approaches, driven by increasing population admixture and advances in genomic technologies [1] [2]. Next-generation sequencing has enabled the development of expanded carrier screening panels that simultaneously assess hundreds of genes associated with recessive disorders without ethnic predilection [10] [2]. Recent large-scale studies demonstrate the clinical utility of this approach, with approximately 24% of individuals identified as carriers of at least one mutation, and 1 in 280 couples at risk of having affected offspring [2].

The implementation of expanded carrier screening in diverse populations is revealing unexpected epidemiological patterns. A 2025 study of 6,308 individuals in Southern Central China utilizing a 147-gene panel found an overall carrier rate of 38.43%, with α-thalassemia, GJB2-associated hearing loss, Krabbe disease, and Wilson's disease representing the most prevalent conditions [10]. This data underscores the importance of population-specific carrier frequency data in designing effective screening programs.

Research Implications and Future Directions

The historical foundations of Tay-Sachs and hemoglobinopathy screening continue to inform contemporary research in several critical areas:

Methodological Development:

- Refinement of high-throughput screening platforms for diverse populations

- Integration of bioinformatics pipelines for variant interpretation

- Development of standardized classification systems for disease severity [2]

Implementation Science:

- Optimization of pre-test and post-test counseling frameworks

- Development of educational resources for healthcare providers and patients

- Establishment of cost-effective screening algorithms for healthcare systems [10] [2]

Ethical and Social Considerations:

- Addressing implications of incidental findings and variants of uncertain significance

- Ensuring equitable access to genetic screening across diverse populations

- Developing culturally competent counseling approaches [2]

The continued evolution of carrier screening from its origins in Tay-Sachs and hemoglobinopathy programs to contemporary pan-ethnic approaches represents a paradigm shift in preventive genetics. These historical foundations provide critical insights for researchers and clinicians working to expand and improve carrier screening protocols, ultimately reducing the burden of recessive genetic disorders through informed reproductive decision-making.

Expanded Carrier Screening (ECS) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in reproductive medicine, moving from a fragmented, ethnicity-based risk assessment to a comprehensive, pan-ethnic approach for identifying carriers of recessive genetic disorders. This transformation is driven by converging advances in genomic technologies, economic evidence, and evolving professional guidelines. Where traditional carrier screening focused on a limited number of conditions in specific high-risk populations, ECS simultaneously analyzes hundreds of genes associated with serious inherited conditions, regardless of an individual's stated ethnic background [10]. This scientific and clinical evolution is occurring within a crucial context: collectively, rare genetic diseases affect an estimated 300-400 million people globally, with approximately 72-80% having a known genetic origin [11]. The implementation of ECS enables at-risk couples to make informed reproductive decisions with the potential to significantly reduce the incidence of these conditions in subsequent generations.

Quantitative Drivers for the Paradigm Shift

Clinical Detection Rates and Carrier Frequencies

Recent large-scale studies demonstrate the superior detection power of ECS compared to traditional approaches. A 2025 study of 6,308 individuals in Southern Central China utilizing a 147-gene panel found that approximately 38.43% (2,424/6,308) of participants were carriers for at least one of 155 genetic conditions [10]. This high carrier prevalence underscores the limitation of ethnicity-based screening, which would have missed many at-risk couples. The study identified 36 at-risk couples from 1,357 tested pairs (2.65%), indicating a substantial number of pregnancies potentially affected without screening [10].

Table 1: Carrier Frequency and At-Risk Couple Identification in a Southern Central China Cohort (2025)

| Screening Parameter | Result | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort Size | 6,308 individuals (5,104 females, 1,204 males) | Large-scale implementation feasibility |

| Panel Size | 147 genes, 155 conditions | Comprehensive coverage beyond traditional panels |

| Overall Carrier Rate | 38.43% (2,424/6,308) | High cumulative frequency of recessive carriers |

| Recall Rate for Partner Testing | 68.93% (1,351/1,960) | Sequential testing acceptance rate |

| At-Risk Couples Identified | 2.65% (36/1,357 tested couples) | Pregnancies with 25% risk for affected offspring |

| Most Prevalent Conditions | α-thalassemia, GJB2-associated hearing loss, Krabbe disease, Wilson's disease | Population-specific findings inform panel design |

Economic Evidence and Cost-Effectiveness

The economic argument for universal ECS has become increasingly compelling. A 2025 microsimulation analysis projected the cost-effectiveness of population-based expanded reproductive carrier screening for 569 genetic diseases in Australia [12]. The model compared different screening strategies over a 40-year horizon and found that at a 50% uptake rate, expanded RCS was cost-saving (delivering higher quality-adjusted life-years at lower costs) compared to both no population screening and limited screening for only three conditions (cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and fragile X syndrome) [12].

Table 2: Cost-Effectiveness Projections of Expanded RCS (569 Conditions) vs. Limited Screening

| Economic Metric | Limited Screening (3 conditions) | Expanded RCS (569 conditions) | Projection Horizon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affected Births Averted (per cohort) | 84 | 2,067 | Single birth cohort |

| Health Service Cost Trajectory | Increase of 20% annually to A$73.4B | Cost-saving | To year 2061 |

| Perspective | Healthcare system & societal | Healthcare system & societal | To year 2061 |

| Key Cost Driver | Lifetime treatment for affected individuals | Upfront screening with averted downstream costs | Lifetime |

The study further highlighted that the direct treatment cost associated with current limited screening would increase by 20% each year, reaching A$73.4 billion to the health system by 2061 without intervention, whereas expanded RCS would avert these costs through prevention [12]. This represents a powerful economic argument for healthcare systems to adopt universal ECS approaches.

Key Implementation Protocols

Core ECS Laboratory Workflow Protocol

The technical implementation of ECS relies on standardized next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows that ensure comprehensive variant detection across multiple genes simultaneously.

Protocol: Expanded Carrier Screening Wet-Lab Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Collect peripheral blood in EDTA tubes from consenting individuals. Extract genomic DNA using validated kits (e.g., QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits). Quantify and quality-check DNA using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) or fluorometry [10].

- Library Preparation and Target Enrichment: Design sequence-enrichment probes to capture coding exons and flanking intronic sequences (typically ± 30 base pairs) for all genes in the screening panel. Use these probes to create sequencer-ready libraries from patient DNA, ensuring high and uniform coverage of all targeted regions [10].

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Perform massively parallel sequencing on an approved NGS platform. The Jiangxi study and commercial providers (e.g., QIAGEN's QIAseq ECS Panel) utilize this approach to achieve the high throughput and accuracy required for population screening [13] [10].

- Variant Calling and Validation: Implement a bioinformatics pipeline for the identification of small nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions or deletions (Indels), and specific copy number variations (CNVs), including exon-level deletions/duplications. For certain genes like HBA/HBB (hemoglobinopathies) and SMN1 (spinal muscular atrophy), special attention is required for technically challenging variants. Orthogonal validation methods (e.g., Sanger sequencing, MLPA) may be used for confirmatory testing [10].

Bioinformatic Analysis and Clinical Interpretation Protocol

The computational analysis and interpretation of sequencing data are critical for accurate carrier identification.

Protocol: Data Analysis and Variant Interpretation

- Variant Annotation and Filtration: Process raw sequencing data through clinical decision support software (e.g., QCI Interpret from QIAGEN) for annotation against curated biomedical literature, professional guidelines, and population databases [13]. Filter variants based on population frequency, predicted pathogenicity, and quality metrics.

- Variant Classification: Classify variants according to established guidelines (e.g., ACMG/AMP 2015 standards) into categories such as "pathogenic," "likely pathogenic," "variant of uncertain significance," "likely benign," or "benign" [10]. Only report pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants for carrier status determination.

- Carrier Status Determination: An individual is identified as a carrier if they harbor at least one pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in an autosomal recessive gene, or if they have a variant in an X-linked gene consistent with carrier status. The laboratory report should clearly state the condition, gene, inherited mode, and specific variants found.

- At-Risk Couple Identification: A couple is identified as being at-risk if both partners are carriers for pathogenic variants in the same autosomal recessive gene, or if the female is a carrier for a pathogenic variant in an X-linked gene [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for ECS Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function in ECS Workflow | Example Product/Technology |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality genomic DNA isolation from clinical samples (e.g., blood). | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (QIAGEN) [10] |

| Targeted Enrichment Panels | Capture coding exons and flanking regions of genes on the ECS panel for sequencing. | QIAseq Expanded Carrier Screening Panel [13] |

| NGS Sequencers | High-throughput platform to simultaneously sequence all target genes from multiple samples. | Illumina, Ion Torrent platforms |

| Variant Databases | Manually curated resource for classifying identified variants as disease-causing. | HGMD Professional [13] |

| Clinical Decision Support Software | Aid in variant annotation, filtering, triage, and interpretation for clinical reporting. | QCI Interpret, QCI Interpret Translational [13] |

| Orthogonal Validation Kits | Confirmatory testing for specific variant types (e.g., CNVs, challenging SNVs). | MLPA kits for SMN1 deletion, Sanger sequencing |

| N-Desmethylthiamethoxam-D4 | N-Desmethylthiamethoxam-D4, MF:C7H8ClN5O3S, MW:281.71 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Linaclotide (Standard) | Linaclotide (Standard), MF:C59H79N15O21S6, MW:1526.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Decision Pathway for Clinical Management of ECS Results

The clinical utility of ECS is realized through structured pathways that guide patients from result disclosure to reproductive decision-making. The following pathway outlines the critical steps following carrier identification.

Discussion: Integrating the Drivers for Change

The paradigm shift toward universal expanded carrier screening is supported by a powerful convergence of evidence. Technological advances in NGS have made simultaneous screening of hundreds of genes technically feasible and increasingly affordable [10]. Clinical utility is demonstrated by large-scale studies showing significant carrier identification rates (~38%) and at-risk couple detection (~2.65%) that would be missed by traditional screening [10]. The economic argument has been solidified by robust modeling showing that population-based ECS is cost-saving for health systems compared to limited screening, primarily by averting the substantial lifetime costs of care for affected individuals [12].

Critical to this shift is the move away from ethnicity-based screening. As professional guidelines like those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) now state, "carrier screening for a particular condition...should be offered to her (regardless of ethnicity and family history)" [14]. This is crucial in an era of increasing multi-ethnic backgrounds, where self-reported ethnicity is a poor predictor of genetic risk [12].

Despite the clear benefits, challenges remain. A 2021 study found that 27% of individuals identified as carriers did not complete subsequent partner screening, and the cost of ECS was not covered by insurance for 54.5% of patients, with nearly half paying over $300 out-of-pocket [15]. Addressing these implementation barriers through improved counseling, insurance coverage, and public health initiatives is essential for realizing the full potential of universal ECS in reducing the burden of recessive genetic disorders.

Current Epidemiology and Global Burden of Recessive Genetic Disorders

Autosomal recessive (AR) disorders constitute a significant global public health burden, affecting an estimated 1.7–5 in 1000 neonates, which surpasses the incidence of autosomal dominant disorders (1.4 in 1000) [16]. Despite their clinical importance, the epidemiology and molecular genetics of many AR diseases remain poorly characterized, creating critical knowledge gaps for researchers and public health professionals [16]. Understanding the genetic underpinnings of AR diseases is paramount for clinical genetics and global health initiatives, particularly as these disorders collectively impact hundreds of millions worldwide [11]. This application note examines the current epidemiological landscape of recessive genetic disorders, highlighting population-specific risk variations, methodological approaches for carrier frequency estimation, and the implications for research and carrier screening programs within the broader context of advancing recessive genetic disorder research.

Epidemiological Landscape of Recessive Disorders

Global Prevalence and Distribution

Recessive genetic disorders, while individually rare, collectively represent a substantial health burden affecting approximately 300–400 million people globally [11]. Epidemiological research reveals striking differences in the prevalence and distribution of these conditions across diverse populations and geographic regions.

Table 1: Global Epidemiology of Selected Autosomal Recessive Disorders

| Disorder | Gene | Overall Carrier Frequency | High-Risk Populations | Population-Specific Carrier Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Anemia | HBB | 1 in 66.6 (1.50%) [17] | African | 1 in 22 (4.54%) [17] |

| Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR | Varies significantly [16] | European, Ashkenazi Jewish | 1 in 40 (2.48%) in Europeans [16] |

| Tay-Sachs Disease | HEXA | Rare in general population [16] | Ashkenazi Jewish | 1 in 3,584 [16] |

| Biotinidase Deficiency | BTD | 1 in 29 (3.5%) [16] | Global | Varies across populations [16] |

| Hemochromatosis | HFE | 1 in 29 (3.4%) [16] | European | 1 in 9 (11.53%) in Europeans [16] |

| Autosomal Recessive Inborn Errors of Metabolism (ARIEM) | 235 genes | 1 in 3 individuals is a carrier [18] | European Finnish | 9 in 10,000 live births [18] |

Analysis of 508 genes associated with 450 AR disorders based on sequencing data from 141,456 individuals across seven major ethnogeographic groups reveals that 101 AR diseases (27%) are limited to specific populations, while an additional 305 diseases (68%) show more than tenfold variation in prevalence across different ethnogeographic groups [16]. This remarkable heterogeneity underscores the importance of population-specific approaches to both research and clinical care.

For rare inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs), recent data suggests that approximately one-third of the global population carries a pathogenic variant responsible for a rare autosomal recessive IEM, with the highest carrier frequency observed in Ashkenazi Jewish populations [18]. Globally, approximately 5 per 1000 live births are affected by an autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism, with European Finnish populations experiencing the highest burden at 9 out of 10,000 live births [18]. Based on these carrier rates, India, with 25 million live births annually, is projected to have at least 8,025 newborns with an ARIEM each year [18].

Population-Specific Genetic Architecture

The molecular genetic underpinnings of AR disorders display remarkable population-specificity, with founder effects and consanguinity driving substantial variations in disease prevalence and mutational spectra.

Table 2: Population-Specific Founder Mutations and Risk Factors

| Population Group | Genetic Risk Factors | Example Disorders with Elevated Frequency | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashkenazi Jewish | Founder mutations [16] | Tay-Sachs, Gaucher, Canavan [16] | Genetic drift, founder effect [19] |

| African Descent | Protective advantage against malaria [19] | Sickle Cell Anemia [16] [19] | Evolutionary selection pressure [19] |

| Arab Populations | High consanguinity rates (20-50% of marriages) [19] | Thalassemia, inborn errors of metabolism [19] | Socio-cultural marriage practices [19] |

| European Finnish | Founder effect, genetic isolation [18] | Various ARIEMs [18] | Population bottleneck, genetic isolation [19] |

| Island Populations (e.g., Iceland, Orkney) | Founder effect [19] | BRCA mutations, various rare disorders [19] | Genetic isolation, limited migration [19] |

| Remote Communities (e.g., Serrinha dos Pintos, Brazil) | High consanguinity (>30% of couples) [19] | SPOAN syndrome [19] | Geographical and cultural isolation [19] |

Population genetics has revealed that rare disease risks are not evenly distributed worldwide but vary significantly between populations due to social, historical, and environmental factors that shape a population's genetic makeup [19]. Consanguineous marriages, defined as unions between second cousins or closer relatives, represent a major risk factor for recessive genetic disorders, as they increase the probability that offspring will inherit identical disease-causing mutations from both parents [19]. In Arab nations, where consanguinity rates range from 20-50% of all marriages, there is a corresponding high incidence of rare Mendelian diseases including intellectual impairments, skeletal dysplasia, and neurodevelopmental problems [19].

Founder effects, where small, isolated populations amplify variants that were rare globally, further contribute to the disparate distribution of AR disorders [19]. Iceland provides a classic example, where a few original settlers carried mutations that became common in later generations [19]. Similar effects have been observed in island populations such as Orkney in Scotland, where BRCA mutations associated with breast cancer occur at higher rates [19].

Methodological Approaches for Epidemiological Research

Population Genomics and Carrier Frequency Estimation

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized the epidemiological study of recessive genetic disorders by enabling comprehensive analysis of genetic variation across diverse populations. The integration of large-scale genomic datasets allows researchers to estimate population-specific carrier frequencies with unprecedented accuracy.

Experimental Protocol: Population-Based Carrier Frequency Estimation

Objective: To determine population-specific carrier rates for autosomal recessive disorders using large-scale genomic datasets.

Materials and Reagents:

- Population genomic datasets (1000 Genomes, gnomAD, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project) [17]

- Variant annotation databases (ClinVar, OMIM, dbSNP) [16]

- Bioinformatics pipeline for variant filtering and annotation

- Pathogenicity prediction algorithms (10 complementary algorithms) [16]

- Statistical analysis software (R, Python) for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium calculations

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain exome or genome sequencing data from diverse population cohorts. The analysis of 141,456 individuals across seven ethnogeographic groups provides robust sample sizes for most populations [16].

- Variant Identification: Extract all variants within 508 genes associated with 450 AR disorders. A typical analysis may encompass 574,524 total variants [16].

- Pathogenicity Assessment: Integrate documented pathogenic variants from ClinVar with stringent computational predictions for variants of unknown significance. This combined approach has been validated to yield the highest accuracy for disease prevalence prediction (r=0.68, p<0.0001) [16].

- Carrier Frequency Calculation: Compute allele frequencies for pathogenic variants in each population group. Under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, carrier frequency can be approximated as 2 × p × q, where p is the minor allele frequency and q is the major allele frequency (for p<0.05; q>0.95) [17].

- Validation: Compare calculated incidences with clinically observed disease frequencies for disorders with established epidemiological data (e.g., 85 validated diseases) [16].

- Disease Burden Estimation: Project disease incidence based on carrier frequencies and population demographics, incorporating live birth data for specific regions or countries [18].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

The epidemiological study of recessive disorders requires careful consideration of several methodological challenges. For conditions with extensive allelic heterogeneity, such as Stargardt disease (ABCA4, 528 pathogenic variants) and cystic fibrosis (CFTR, 408 pathogenic variants), comprehensive variant detection is essential for accurate carrier frequency estimation [16]. Furthermore, the validation of epidemiological models against clinically observed prevalence data is crucial, with recent studies demonstrating strong correlation between predicted and observed disease frequencies (r=0.68, p<0.0001) for 85 well-characterized AR disorders [16].

Population-specific founder mutations require particular attention in research design. For example, while the p.Phe508del mutation in CFTR accounts for 72% of cystic fibrosis cases in Caucasians, the p.Trp1282Ter variant is the most prevalent in Ashkenazi Jews (46% of cases) [16]. Similarly, Wilson disease demonstrates population-specific genetic underpinnings, being primarily attributed to p.His1069Gln in Ashkenazim and Europeans but to p.Arg778Leu in East Asians [16]. These differences highlight the necessity of population-informed research approaches and screening panels.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reproductive Carrier Screening Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Cases | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput analysis of multiple genes simultaneously [20] | Expanded carrier screening panels [20] | Enables comprehensive testing beyond ethnicity-based approaches [20] |

| Population Genomic Datasets | Reference data for allele frequency filtering [16] [17] | Pathogenicity assessment, determining population-specific variants [16] | Must include diverse ethnogeographic groups for global applicability [16] |

| Variant Annotation Databases (ClinVar, OMIM) | Curated information on disease-associated variants [16] | Pathogenicity classification, clinical interpretation [16] | Regular updates essential for incorporating new discoveries [16] |

| Computational Prediction Algorithms | In silico assessment of variant pathogenicity [16] | Interpretation of variants of unknown significance [16] | Combination of multiple algorithms improves accuracy [16] |

| Biobank Samples with Clinical Data | Validation of genotype-phenotype correlations [19] | Association studies, penetrance estimation [19] | Critical for connecting rare disease genetics with real-world healthcare planning [19] |

The research reagents outlined in Table 3 form the foundation for contemporary epidemiological and clinical research on recessive genetic disorders. Next-generation sequencing platforms, in particular, have revolutionized carrier screening by enabling the simultaneous analysis of hundreds of genes, moving beyond the limitations of ethnicity-based screening approaches [20]. The integration of population genomic datasets with advanced computational prediction algorithms has further enhanced the accuracy of carrier risk assessment, particularly for populations historically underrepresented in genetic research [16].

The current epidemiological landscape of recessive genetic disorders reveals significant global burden with marked population-specific variations. The integration of large-scale genomic data has enabled unprecedented resolution in understanding the prevalence, distribution, and genetic complexity of these conditions. Methodological advances in population genomics and bioinformatics now permit accurate estimation of carrier frequencies and disease incidence across diverse populations, providing valuable insights for public health planning and resource allocation. These epidemiological research approaches form the critical foundation for developing targeted carrier screening programs, informing drug development priorities, and advancing global health initiatives aimed at reducing the burden of recessive genetic disorders. Future research directions should prioritize inclusion of underrepresented populations, refinement of pathogenicity prediction algorithms, and translation of epidemiological findings into improved clinical care and prevention strategies.

Reproductive genetic carrier screening (RGCS) has emerged as a powerful tool in clinical genetics, enabling the identification of asymptomatic individuals who carry genetic variants for autosomal recessive or X-linked conditions. The fundamental tension in implementing RGCS programs lies in defining their primary objective: is the goal to enhance individual reproductive autonomy or to achieve public health prevention by reducing the population prevalence of severe genetic disorders? This application note examines these competing paradigms, provides structured quantitative data, and outlines essential protocols for researchers and drug development professionals working in this field.

Quantitative Landscape of Carrier Screening

Analysis of current literature and large-scale studies reveals key quantitative benchmarks essential for program planning and evaluation.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics from Carrier Screening Studies

| Metric | Value | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| General Population Carrier Couple Risk | 1–2% | Risk of having a child with a recessive genetic condition [21] |

| Expanded Carrier Screening (ECS) Couple Risk | 1.9% | Mackenzies Mission study (>9000 couples) [22] |

| Affected Births for Rare Diseases | 1 in 280 births | General population baseline [23] |

| Tay-Sachs Disease Incidence Reduction | >90% | Ashkenazi Jewish populations post-screening [24] |

| Engagement Cancellation Rate | 23% | Couples with positive results in Omani premarital program [22] |

| Planned Risk Avoidance | >75% | Newly identified carrier couples in Mackenzies Mission [22] |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Screening Paradigms

| Feature | Public Health Prevention Paradigm | Reproductive Autonomy Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Aim | Reduce disease prevalence in populations [24] | Enable informed reproductive decision-making [24] [22] |

| Historical Context | Targeted high-risk populations (e.g., Tay-Sachs, β-thalassemia) [24] | Pan-ethnic expanded panels (e.g., Mackenzie's Mission) [22] |

| Key Outcome Measures | Incidence reduction, cost savings [22] | Informed choice, psychological outcomes [24] |

| Ethical Considerations | Potential stigmatization, directive counseling [24] | Equity of access, non-directive counseling [24] [25] |

| Notable Examples | Tay-Sachs in Ashkenazi Jews, thalassemia in India [24] [22] | Mackenzie's Mission (Australia), ECS in Netherlands [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Carrier Screening Research

Protocol: Expanded Carrier Screening Workflow Using Next-Generation Sequencing

Principle: Simultaneous analysis of multiple disease-related genes via high-throughput sequencing to determine carrier status irrespective of ethnicity or family history [23].

Materials & Reagents:

- DNA Sample: 50–100 ng of genomic DNA from peripheral blood or saliva.

- Library Preparation Kit: Illumina Nextera Flex or equivalent.

- Sequence Capture Panel: Commercially available ECS panel (e.g., 100–500+ genes associated with recessive disorders).

- NGS Platform: Illumina NovaSeq, MiSeq, or similar.

- Bioinformatics Pipeline: BWA-GATK or equivalent for variant calling; ANNOVAR or SnpEff for annotation.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Obtain informed consent. Collect venous blood in EDTA tubes or saliva in Oragene kits. Extract DNA using automated magnetic bead-based systems (e.g., QIAsymphony) [23].

- Library Preparation & Target Enrichment: Fragment DNA and attach sequencing adapters. Hybridize to biotinylated probes targeting the ECS gene panel. Perform capture with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads [23].

- Sequencing: Pool libraries and sequence on NGS platform to achieve >50x mean coverage across target regions, with >95% of bases covered at ≥30x [23].

- Variant Calling & Annotation: Align reads to reference genome (GRCh38). Call variants and filter against population databases (gnomAD). Annotate for pathogenicity using ClinVar and disease-specific databases.

- Interpretation & Reporting: Classify variants according to ACMG guidelines. Report pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in genes associated with severe, penetrant, childhood-onset conditions. Exclude variants associated with adult-onset disorders to protect future child autonomy [24].

Protocol: Assessing Outcomes and Psychological Impact

Principle: Evaluate whether screening programs achieve reproductive autonomy through validated measures of informed decision-making and psychological outcomes [24] [25].

Materials:

- Validated Questionnaires:

- Multidimensional Measure of Informed Choice (MMIC): Assesses knowledge, attitudes, and uptake consistency.

- Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS): Measures uncertainty in decision-making.

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): Screens for psychological distress.

- Structured Interview Guides: Qualitative exploration of decision-making processes.

Procedure:

- Pre-Test Assessment (T0): Administer questionnaires assessing baseline knowledge, attitudes toward screening, and anxiety levels before test offer [25].

- Post-Test Counseling Session: Provide results with non-directive genetic counseling. Document reproductive intentions and understanding.

- Post-Test Assessment (T1): Administer follow-up questionnaires within 2–4 weeks after result disclosure, assessing decisional conflict, anxiety, and satisfaction.

- Long-Term Follow-Up (T2): Conduct structured interviews at 6–12 months to document actual reproductive behaviors (e.g., pursuit of PGT-M, prenatal diagnosis, pregnancy outcomes) [22].

- Data Analysis: Quantitative analysis of questionnaire scores; qualitative thematic analysis of interview transcripts. Correlate outcomes with demographic variables and result status.

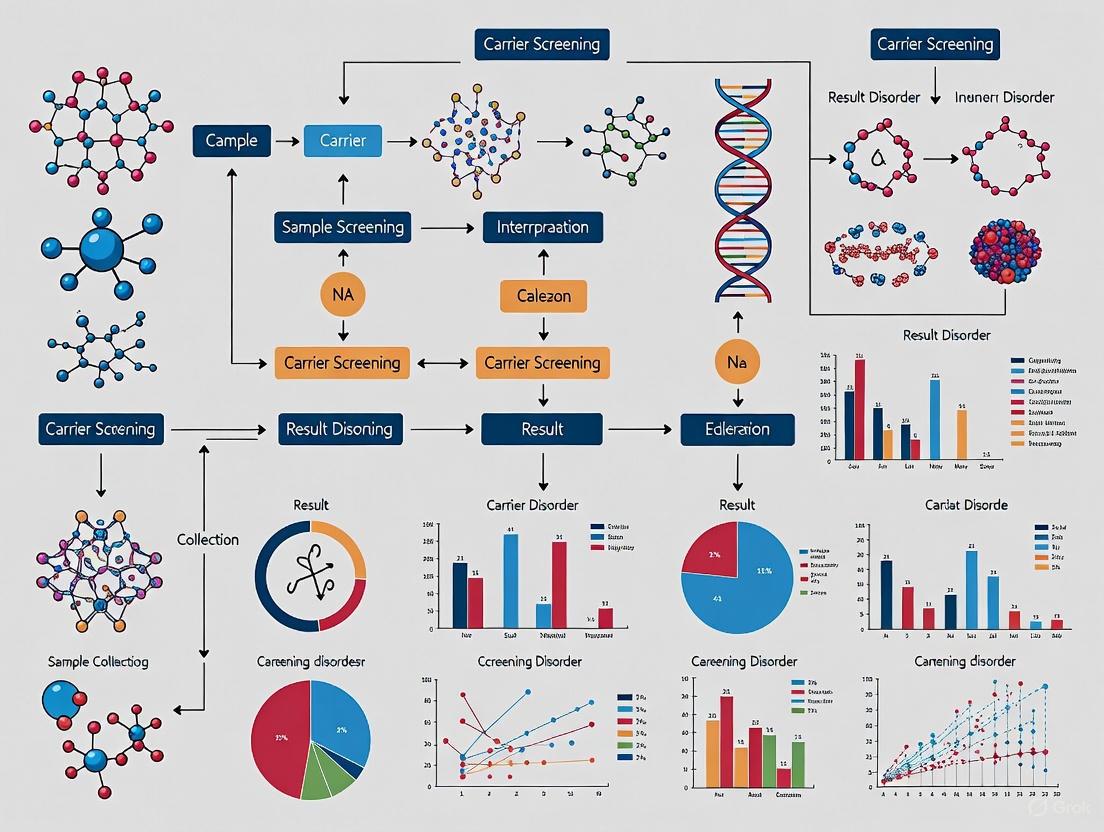

Visualizing Screening Pathways and Decisions

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Carrier Screening Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencer | High-throughput DNA sequencing for ECS panels [23] | Illumina NovaSeq 6000, MiSeq Dx; >50x coverage required |

| Targeted Capture Panels | Enrichment of disease-associated genes prior to sequencing [23] | Commercially available ECS panels (e.g., Illumina, Twist Bioscience); 100–500+ genes |

| Bioinformatics Pipeline | Variant calling, annotation, and interpretation [23] | BWA-MEM, GATK, VEP; integration with population databases (gnomAD) |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from clinical samples | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, MagMAX DNA Multi-Sample Kit |

| Genetic Counseling Protocols | Standardized pre- and post-test counseling to ensure informed choice [25] | Non-directive approach; covers test limitations, reproductive options, psychological impact |

| Decision Aid Tools | Support informed decision-making for screening participants [25] | Visual aids, quantitative risk calculators, value clarification exercises |

Ethical and Societal Considerations in Population-Wide Screening Implementation

Reproductive genetic carrier screening (RGCS) has evolved from a niche practice targeting specific high-risk populations to a comprehensive public health strategy applicable to all prospective parents [24]. This transition toward population-wide screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions raises profound ethical and societal questions that must be addressed for responsible implementation [24] [26]. The core tension lies in balancing the promise of enhanced reproductive autonomy against concerns about potential societal consequences, including the stigmatization of disability and unjust distribution of healthcare resources [24] [27]. This application note examines these complexities within the broader context of carrier screening research, providing frameworks and protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in navigating this rapidly evolving field. The shift from ethnicity-based to pan-ethnic screening represents not merely a technological advancement but a fundamental reorientation of the ethical foundations of carrier screening [22] [28].

Ethical Frameworks and Tensions

Primary Ethical Tensions in RGCS Implementation

The ethical landscape of population-wide RGCS is characterized by several interconnected tensions that researchers and policymakers must navigate. The table below summarizes the core ethical considerations and their practical implications for screening programs.

Table 1: Core Ethical Considerations in Population-Wide RGCS Implementation

| Ethical Principle | Traditional Screening Model | Population-Wide Screening Model | Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Aim | Reduce prevalence of specific genetic disorders [24] | Enhance reproductive autonomy [24] [22] | Tension between public health goals and individual choice [24] |

| Target Population | High-risk groups based on ethnicity/family history [24] [29] | All prospective parents regardless of background [24] [28] | Potential for missing specific at-risk variants in founder populations [24] |

| Equity Considerations | Perpetuated disparities in access [29] | Aims to provide equitable access [24] [28] | Requires addressing historical medical racism and building trust [29] |

| Condition Selection | Limited to conditions prevalent in specific populations [24] | Expanded panels (100+ conditions) [24] [22] | No consensus on definition of "severe" conditions warranting inclusion [24] [27] |

Historical Context and Equity Imperatives

The historical legacy of genetic screening necessitates careful attention to equity in modern RGCS implementation. Early carrier screening initiatives were characterized by targeted approaches based on perceived ethnic risk, which created significant disparities in care [29]. This approach was problematic not only because it overlooked the genetic diversity within all populations but also because it "perpetuated elements of systemic racism within the United States healthcare system" [29]. The movement toward universal, pan-ethnic screening panels presents an opportunity to rectify these historical inequities by offering all individuals the same comprehensive screening regardless of self-reported race or ethnicity [24] [29].

However, simply expanding screening access is insufficient without addressing deeper structural barriers. Historical atrocities including forced sterilizations, immigration restrictions based on eugenic philosophies, and abuses such as the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee have created justifiable distrust of genetic medicine among marginalized communities [29]. Research indicates that minority groups, including Latino communities, may be less well-served by carrier screening education and outreach despite expressing interest in genetic health information [22] [28]. Successful implementation must therefore involve community engagement, cultural competence, and transparent informed consent processes that acknowledge this troubled history [29].

Stakeholder Perspectives and Severity Considerations

Understanding stakeholder perspectives is critical for ethical RGCS implementation. Recent qualitative research involving prospective parents without a personal or family history of genetic conditions reveals strong support for comprehensive screening options, though with important nuances [30]. Participants in a 2025 Australian study expressed desire for a tiered approach to carrier screening that would allow them to select the severity of conditions included based on their personal values and preferences [30].

Table 2: Stakeholder Perspectives on Condition Inclusion in RGCS

| Stakeholder Group | Support for RGCS | Preferences Regarding Condition Inclusion | Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective Parents (general population) | High support for severe conditions; decreases with milder conditions [30] [27] | Preference for tiered approaches allowing personal choice; value in choice and knowledge [30] | Societal impacts of broad screening; potential for eugenic applications [30] |

| Relatives of Patients with genetic conditions | Support offering carrier screening, particularly for severe disorders [22] [28] | Focus on conditions with significant impact on quality of life [22] | - |

| Healthcare Providers | Professional guidelines recommend offering RGCS to all [24] [30] | Emphasis on conditions where results would impact reproductive decision-making [24] [25] | Need for genetic counseling resources; ensuring informed consent [25] |

Defining and Applying Severity Criteria

The concept of condition severity represents a central challenge in designing ethically defensible RGCS programs. International guidelines consistently recommend focusing on "severe" conditions but lack precise definitions for this term [27]. Research indicates that severity is a multidimensional construct influenced by factors including age of onset, impact on daily functioning, life expectancy, availability of treatments, and cognitive impact [27]. A defensible approach to defining severity must incorporate multiple perspectives, including those of clinicians, researchers, and most importantly, individuals with lived experience of genetic conditions [27].

The diagram below illustrates the recommended multidisciplinary approach to defining severity criteria for RGCS programs:

Multidisciplinary Severity Assessment for RGCS

This integrated approach acknowledges that severity cannot be determined by clinical metrics alone but must incorporate the subjective experiences of affected individuals and families while considering broader societal implications [27]. For conditions with highly variable expressivity or incomplete penetrance, such as cystic fibrosis, decisions about inclusion should reflect the likely value of genetic information for reproductive decision-making [27]. Research indicates that as conditions become clinically milder, both support for their inclusion in screening panels and the likelihood that couples would use reproductive options to avoid having children with the condition decrease significantly [27].

Implementation Protocols and Guidelines

Structured Implementation Framework

Successful population-wide RGCS requires careful program design and standardized protocols. The following workflow outlines key stages in RGCS implementation, from pre-test counseling to result management:

RGCS Program Implementation Workflow

Essential Protocol Components

Pre-Test Counseling and Informed Consent Protocol

Effective RGCS implementation requires comprehensive pre-test counseling that addresses several key elements [25]. Counseling should be viewed as an essential component rather than an optional addition, though accessibility to genetic counselors may be limited by resources and social determinants of health [25]. The protocol should include:

- Interpretation of family and medical histories to assess risk of disease occurrence or recurrence, while acknowledging that RGCS is designed for those without known risk factors [25]

- Education about inheritance patterns and disease severity of conditions being screened, including the difference between carrier status and affected status [25]

- Discussion of potential outcomes, including the possibility of identifying variants of uncertain significance, incidental findings, and the limitations of screening [24] [25]

- Explanation of reproductive options available for carrier couples, including prenatal diagnosis, preimplantation genetic testing, use of donor gametes, or adoption [24]

- Review of psychological implications and the potential impact on family dynamics [25]

Laboratory Analysis and Technical Standards

Modern RGCS programs utilize next-generation sequencing technologies to simultaneously analyze hundreds of genes associated with serious genetic conditions [24] [31]. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommends screening for autosomal recessive conditions with a carrier frequency of ≥1 in 200 [30]. Technical protocols should address:

- Gene selection criteria based on severity, penetrance, and population frequency [24] [27]

- Variant interpretation and classification protocols, recognizing the European ancestry bias in many genomic databases [24] [29]

- Specialized approaches for technically challenging genes (e.g., FMR1 for fragile X, SMN1 for spinal muscular atrophy) that may require long-read sequencing technologies [31]

- Quality control measures and participation in proficiency testing programs [25]

Research Tools and Technical Considerations

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines key research reagents and platforms used in advanced carrier screening research:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Carrier Screening

| Research Tool | Manufacturer/Developer | Primary Application in RGCS Research | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| PureTarget Carrier Screening Panel | PacBio [31] | Comprehensive analysis of inherited conditions, including ACMG tier 3 genes | HiFi long-read sequencing resolves challenging genomic regions; replaces multiple legacy assays [31] |

| PureTarget Repeat Expansion Panel | PacBio [31] | High-resolution analysis of neurological disease-associated tandem repeats | Directly captures repeat expansions without PCR; identifies non-canonical repeat motifs [31] |

| PureTarget Control Panel | PacBio [31] | Custom assay design and validation for population-specific research | Enables tailoring to specific populations or research priorities [31] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms | Various [24] [22] | High-throughput screening of multiple gene simultaneously | Scalable; cost-effective for large panels; identifies variants regardless of ethnic background [24] [28] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation Protocols

Accurate interpretation of RGCS results requires robust bioinformatics pipelines and careful consideration of population genetics. Key methodological considerations include:

- Variant annotation and filtering using population frequency databases, with recognition of the limitations posed by under-representation of diverse populations [24] [29]

- Haplotype analysis for conditions where specific haplotype backgrounds impact clinical interpretation (e.g., SMN1/SMN2 in spinal muscular atrophy) [31]

- Copy number variation detection to identify exon-level deletions and duplications that may be missed by sequencing alone [31]

- Risk calculation based on carrier frequencies and residual risk estimates after negative results [25]

Researchers should explicitly document the ethnic composition of reference populations used for frequency filtering and acknowledge limitations in variant interpretation for understudied populations [24]. This transparency is essential for maintaining trust and ensuring equitable application across diverse populations.

Global Perspectives and Future Directions

Population-wide RGCS implementation varies significantly across different healthcare systems and cultural contexts. The Australian "Mackenzie's Mission" study, which screened over 9,000 couples for more than 1,000 genetic conditions, represents one of the largest government-funded research initiatives in this space, identifying 1.9% of screened couples as carrier couples [22] [28]. More than 75% of these newly identified carrier couples indicated they would use this information to avoid the birth of an affected child [22] [28]. In Oman, a premarital screening and counseling program reported that 23% of engaged couples with positive results cancelled their engagements, highlighting the profound personal and social implications of carrier screening [22] [28].

Future developments in RGCS research will likely focus on expanding condition panels while improving the evidence base for inclusion criteria, addressing disparities in genomic databases to ensure equitable benefits across populations, and integrating artificial intelligence for improved variant interpretation and risk prediction [32] [31]. Additionally, research is needed to understand the long-term psychosocial impacts of population-wide carrier screening and to develop best practices for supporting individuals and couples throughout the decision-making process [24] [30].

The successful implementation of population-wide RGCS requires ongoing collaboration between researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and communities to ensure that technological advances translate into ethically responsible and equitable healthcare practices that genuinely enhance reproductive autonomy while respecting the diversity of human experience and values.

Advanced Methodologies and Clinical Workflows in Modern Carrier Screening

Advancements in genomic technologies have fundamentally transformed the landscape of carrier screening for recessive genetic disorders, enabling researchers to move from targeted, ancestry-based testing to comprehensive, pan-ethnic screening approaches [33] [34]. High-throughput technologies—primarily next-generation sequencing (NGS), microarrays, and PCR-based methods—now form the technological foundation for expanded carrier screening (ECS) in research settings [35] [36]. These parallel analysis platforms allow scientists to simultaneously investigate hundreds of genes associated with severe autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions, providing unprecedented insights into population carrier frequencies and the genetic architecture of rare diseases [34] [37]. This application note details the experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and implementation considerations for these core technologies within a research framework focused on preventing severe monogenic diseases.

The selection of an appropriate technological platform depends on the specific research objectives, scale, and variant detection requirements. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary technologies used in high-throughput carrier screening research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Core Technologies in Carrier Screening Research

| Technology | Primary Applications in Carrier Screening | Throughput Capacity | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Full-exon sequencing for 100-500+ genes; novel variant discovery [35] [38] | 100s-1000s of samples per run [35] | Comprehensive mutation detection; pan-ethnic applicability; identifies novel variants [35] [34] | Challenges with pseudogenes, repeat expansions, and structural variants [33] [34] |

| Microarrays | Targeted genotyping of known pathogenic variants; population-specific screening [36] [38] | 96-384 samples per run (array-dependent) [36] | High-throughput; cost-effective for known variants; simplified data analysis [36] | Limited to predefined variants; lower sensitivity for novel mutations [38] |

| PCR-Based Methods | Targeted mutation validation; screening for specific high-frequency mutations; resolving technically challenging loci [36] [37] | 36-384 samples per run (method-dependent) [36] | Rapid, specific detection; gold standard for validation; cost-effective for few targets [37] | Low multiplexing capability; limited scalability [39] |

Each technology platform employs distinct experimental workflows and bioinformatic processes to generate reproducible, high-quality data for research purposes. The following sections provide detailed protocols for their implementation.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Workflow

Protocol: Targeted NGS for Expanded Carrier Screening

Principle: This protocol utilizes hybrid capture or microdroplet PCR-based enrichment of target genes followed by next-generation sequencing to identify pathogenic variants in a high-throughput manner [35].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-Based Carrier Screening

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Target Enrichment System | Captures or amplifies genomic regions of interest | 29,891 RNA baits (120-mer) designed to capture 98.7% of targets across 437 genes [35] |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares DNA fragments for sequencing | Compatible with Illumina, MGI, or PacBio platforms [37] |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline | Variant calling, annotation, and filtration | Stringent bioinformatic filters for SNVs, indels, splicing, and gross deletion mutations [35] |

| Validation Reagents | Confirms positive findings via orthogonal method | Sanger sequencing, MLPA, or qPCR reagents for variant confirmation [37] |

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from peripheral blood using commercial extraction kits (e.g., DNA Extraction Reagent Kit) [37]. Assess DNA quality and quantity via spectrophotometry.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA and ligate platform-specific adapters following manufacturer's protocols. For hybrid capture: Hybridize libraries with biotinylated RNA baits targeting exons, splice sites, and known pathogenic variants of 437 recessive disease genes [35]. For microdroplet PCR: Amplify target regions using primer pairs in water-in-oil emulsion droplets [35].

- Target Enrichment: Capture bait-bound fragments using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (hybrid capture) or break emulsions and pool amplified products (microdroplet PCR).

- Sequencing: Load enriched libraries onto NGS platforms (e.g., MGISEQ-2000, Illumina systems). Sequence to an average depth of ≥100x, with >99% of target bases covered at ≥20x [35] [37].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align sequences to reference genome (e.g., hg19) using BWA or similar tools [37].

- Call variants with SAMtools/GATK and annotate using population and clinical databases [37].

- Apply stringent filters to exclude common polymorphisms and misannotated mutations (27% of literature-cited mutations may require reclassification) [35].

- Validation: Confirm positive mutations using Sanger sequencing for SNVs/indels, gap-PCR for α-thalassemia CNVs, and MLPA/qPCR for other CNVs [37].

Performance Characteristics

In research settings, this NGS approach demonstrates approximately 95% sensitivity and >99.99% specificity for mutation detection when using validated protocols [35] [38]. Research studies report that 93% of targeted nucleotides achieve at least 20x coverage at 160x average depth, enabling reliable variant calling [35]. The average carrier burden for severe pediatric recessive mutations is approximately 2.8 per genome, ranging from 0 to 7 across studied populations [35].

Microarray-Based Screening Workflow

Protocol: High-Throughput Genotyping Array

Principle: This method uses predefined probes on a microarray to simultaneously genotype thousands of known pathogenic variants across hundreds of genes in a single, streamlined assay [36].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microarray-Based Screening

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Carrier Screening Array | Detects predefined pathogenic variants | CarrierScan 1S Assay: >6,000 structural and sequence variants across 600 genes [36] |

| Array Processing Instrument | Automated array hybridization and scanning | Applied Biosystems platforms with compatibility for 96-384 sample formats [36] |

| Data Analysis Software | Interprets fluorescence patterns into genotypes | Custom software for simplified interpretation and reporting of CNVs and SNVs [36] |

Procedure:

- DNA Preparation: Extract DNA and quantify using fluorometric methods. Ensure high-quality DNA (A260/280 ratio 1.8-2.0).

- Whole Genome Amplification: Amplify entire genome using isothermal amplification to generate sufficient material for hybridization.

- Fragmentation and Precipitation: Fragment amplified DNA using controlled enzymatic digestion and precipitate using standard ethanol/salt protocols.

- Resuspension and Hybridization: Resuspend fragmented DNA in hybridization buffer and apply to microarray (e.g., CarrierScan 1S Assay). Incubate 16-24 hours with rotation at appropriate temperature [36].

- Washing and Staining: Perform automated washing and staining using fluorophore-conjugated detection reagents on compatible fluidics stations.

- Scanning and Analysis: Scan arrays using high-resolution scanner and extract fluorescence intensities. Analyze data using manufacturer's software to determine genotype calls for each variant [36].

- Data Interpretation: Apply algorithm-based calling for CNVs and SNVs. Export results in standardized format for research documentation.

Performance Characteristics

Microarray-based screening demonstrates high reproducibility and accuracy for known pathogenic variants, with analytical sensitivity and specificity exceeding 99% for well-characterized SNVs and CNVs [36]. This technology offers a cost-effective solution for large-scale population studies focusing on established mutations, with throughput of 96-384 samples per run depending on the platform configuration [36].

PCR-Based Methods for Targeted Screening

Protocol: High-Throughput Genome Releaser for PCR Screening

Principle: This innovative approach utilizes mechanical disruption for rapid, cost-effective DNA release directly from biological samples, bypassing traditional extraction and enabling efficient PCR screening in high-throughput formats [39].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Collect fungal spores, microbial cells, or other samples in appropriate culture media. For fungal spores, culture for 2-3 days to produce sufficient biomass [39].

- High-Throughput Genome Release: Load samples into custom 96-well plate with solid bottom design. Apply Shear Applicator with cylindrical pins featuring flat bottoms to mechanically disrupt cells through squashing action. Perform side-to-side movement to ensure complete cell disruption [39].

- PCR Setup: Directly use released DNA from squashed samples as PCR template without purification. Combine with PCR master mix, primers, and polymerase.

- Amplification: Run PCR with optimized cycling conditions: Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of: 95°C for 30s, appropriate annealing temperature for 30s, 72°C for 1 min/kb; Final extension: 72°C for 5 min [39].

- Product Analysis: Analyze PCR products by capillary electrophoresis or other detection methods.

Specialized PCR Applications in Carrier Screening

Multiplex PCR for SMN1 Deletions:

- Principle: Amplifies SMN1 exon 7 with simultaneous detection of SMN2 using multiplex PCR and capillary electrophoresis to identify carriers of spinal muscular atrophy [36].

- Procedure: Design primers targeting SMN1/SMN2 homology regions. Perform multiplex PCR with genomic DNA. Analyze products by capillary electrophoresis to distinguish SMN1 from SMN2 amplicons and identify exon 7 deletions [36].

Triplet-Primed PCR for FMR1 Expansion:

- Principle: Detects CGG repeat expansions in FMR1 gene associated with fragile X syndrome using a combination of full-length and triplet-primed PCR [36].

- Procedure: Perform dual PCR system with primers flanking CGG repeat region and (CGG)n-specific primers. Amplify and analyze products by fragment analysis to accurately determine up to 200 CGG repeats and detect larger expansions [36].

Technology Selection Guidelines for Research Applications

The choice between NGS, microarray, and PCR technologies depends on multiple research factors. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate technological approach:

The integration of NGS, microarray, and PCR technologies provides researchers with a powerful toolkit for advancing carrier screening research for recessive genetic disorders. Each platform offers distinct advantages: NGS for comprehensive variant discovery, microarrays for cost-effective high-throughput genotyping, and specialized PCR methods for technically challenging genomic regions. As these technologies continue to evolve, emerging approaches such as long-read sequencing and streamlined workflows promise to further enhance detection capabilities, improve accuracy, and expand the scope of carrier screening research. The protocols and applications detailed in this document provide a foundation for implementing these core technologies in research settings aimed at reducing the incidence of severe recessive genetic disorders through advanced genetic screening approaches.

Carrier screening for recessive genetic disorders represents a cornerstone of modern preventive genetics, empowering individuals with information about their reproductive risks. The accurate detection of carrier status hinges on the precise analysis of key genes, such as SMN1 (spinal muscular atrophy), HBA1/HBA2 (α-thalassemia), and FMR1 (fragile X syndrome) [22]. However, these genes are notoriously challenging for conventional short-read next-generation sequencing (NGS) and Sanger sequencing due to their high genomic complexity, including high homology regions (SMN1/SMN2, HBA1/HBA2), repetitive sequences (FMR1 CGG repeats), and propensity for large structural variants [40] [41] [42]. These technical limitations have historically led to false negatives and incomplete diagnoses, undermining the effectiveness of screening programs [43].

Long-read sequencing (LRS) technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) are revolutionizing the molecular diagnosis of these conditions by generating reads spanning thousands of base pairs. This capability allows for the phased resolution of complex alleles, accurate sizing of repetitive expansions, and comprehensive structural variant detection in a single assay [41] [44]. This application note details specific protocols and data analysis strategies for applying LRS to overcome the persistent technical hurdles in sequencing SMN1, HBA, and FMR1, providing a robust framework for their integration into carrier screening and research.

Technical Challenges and LRS Solutions by Gene

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Challenges and Long-Read Sequencing Advantages by Gene

| Gene | Associated Disorder | Primary Technical Challenge for Short-Reads | Key Long-Read Sequencing Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMN1/SMN2 | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | Near-identical sequence homology (>99.9%) between SMN1 and its paralog SMN2 [40] | Phased sequencing of full-length ~28 kb amplicons distinguishes haplotypes and accurately assigns variants to SMN1 or SMN2 [45] |

| HBA1/HBA2 | α-Thalassemia | High homology (~97%) and complex structural variants arising from misalignment between homologous boxes [46] | Spans entire homologous regions to directly observe large deletions and phase non-deletional variants, identifying cis/trans configurations [47] [43] |

| FMR1 | Fragile X Syndrome | Sizing long CGG triplet repeats (>200 repeats) and detecting AGG interruptions; GC-rich nature causes sequencing failures [42] | Single molecules traverse the entire repeat expansion, providing exact CGG count and AGG interruption patterns without allele dropout [48] [42] |

In-Depth Focus: SMN1 and SMN2

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) carrier screening requires precise determination of SMN1 copy number and identification of intragenic mutations. The c.840C>T difference is the primary paralogous sequence variant used to distinguish SMN1 from SMN2, but conventional NGS cannot phase this variant with distal mutations [40]. The CASMA2 (Comprehensive Analysis of SMA) method utilizes LRS to amplify and sequence two large fragments spanning the entire SMN1/2 genomic loci (~28 kb). This approach directly counts gene copies via haplotype resolution and simultaneously detects point mutations, indels, and silent (2+0) carriers in a single workflow, achieving a >99% concordance with orthogonal methods [45].

In-Depth Focus: HBA1 and HBA2

The α-globin locus is characterized by highly homologous sequences that predispose it to recurrent deletions. Short-read sequencing struggles with unambiguous alignment in this region [46]. LRS overcomes this by spanning the entire duplication unit, allowing for the direct observation of breakpoints for common deletions (e.g., -α3.7, --SEA) and the discovery of novel large deletions, as demonstrated in a Chinese family where a novel 7.4 kb δ/β-globin gene deletion was identified [47]. This capability is critical for determining whether mutations are in cis (on the same chromosome) or trans (on opposite chromosomes), information that is vital for accurate reproductive risk assessment [43].

In-Depth Focus: FMR1

Traditional PCR and Southern blot for FMR1 analysis cannot reliably size large CGG expansions or detect AGG interruptions. LRS provides a comprehensive solution by sequencing single DNA molecules through the entire FMR1 5' UTR. The CAFXS (Comprehensive Analysis of FXS) method simultaneously determines the CGG repeat length, AGG interruption pattern, and methylation status [42]. This comprehensive profiling is crucial for genetic counseling, as AGG interruptions within the CGG repeat tract significantly influence the meiotic stability and transmission risk of premutation alleles to full mutations [42].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive SMN1/2 Analysis (CASMA2)

The CASMA2 protocol is optimized for carrier and newborn screening from both peripheral blood and dried blood spot (DBS) samples [45].

- DNA Extraction: Use high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit). For DBS samples, extract with specialized kits and assess DNA integrity.

- Target Amplification: Perform two long-range PCR reactions using primers specific for:

- Amplicon A (SMN1/2-FL): Covers the full-length ~28.5 kb genomic region of SMN1 and SMN2.

- Amplicon B (SMN1/2-D): Covers a downstream ~26.1 kb region. A third PCR targets the B2M gene as an endogenous reference for normalized copy number analysis.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Pool the PCR products in equimolar ratios. Prepare a SMRTbell library and sequence on the PacBio Sequel II system using the "Circular Consensus Sequencing" mode to generate highly accurate HiFi reads.

- Data Analysis:

- Alignment: Map HiFi reads to a reference genome (GRCh38).