Cross-Validation of Genomic Prediction Models: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation for genomic prediction models, a critical step for ensuring the reliability and generalizability of models in biomedical research and drug development.

Cross-Validation of Genomic Prediction Models: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation for genomic prediction models, a critical step for ensuring the reliability and generalizability of models in biomedical research and drug development. We explore the foundational principles of why cross-validation is indispensable for robust genomic prediction, moving to a detailed examination of core methodologies like k-fold and Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation. The guide addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies, including handling overfitting, data leakage, and computational efficiency. Finally, it offers a framework for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of different models, from traditional BLUP to advanced machine learning methods, empowering scientists to build more accurate and trustworthy predictive tools for clinical and research applications.

The Critical Role of Cross-Validation in Genomic Prediction

In the domain of genomic selection (GS), the primary goal is to predict the genetic merit of breeding candidates using genome-wide molecular markers, thereby accelerating genetic gain in plant and animal breeding programs [1] [2]. Genomic prediction models, however, require robust validation to ensure their predictions will generalize to new, unseen populations. Cross-validation (CV) serves as a fundamental statistical procedure for assessing how the results of a statistical analysis will generalize to an independent data set [3]. It is any of various similar model validation techniques for assessing how the results of a statistical analysis will generalize to an independent data set [3]. In GS, this is critical for estimating the potential accuracy of selections before committing extensive resources to field trials.

The use of cross-validation is particularly important because simply fitting a model to a training dataset and computing the goodness-of-fit on that same data produces an optimistically biased assessment - the model does not need to generalize, it only needs to recall the data it was trained on [3]. This bias is especially pronounced when the number of parameters is large relative to the number of data points, a common scenario in genomic prediction where thousands of markers are used to predict traits [4]. Cross-validation provides an out-of-sample estimate of model performance, which is more indicative of how the model will perform in actual breeding scenarios where selections are made on untested individuals [2] [3].

A Spectrum of Methods: From Simple Holdout to Exhaustive Designs

Cross-validation methods exist on a spectrum, ranging from computationally simple approaches to exhaustive designs that use the entire dataset for both training and validation. These methods can be broadly categorized as non-exhaustive (holdout and k-fold) and exhaustive (leave-p-out and leave-one-out) approaches [3]. The choice among these methods involves trade-offs between bias, variance, computational expense, and suitability for specific data structures commonly encountered in genomic studies, such as family structures or longitudinal measurements [2].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the primary cross-validation methods relevant to genomic prediction research:

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Validation Methods in Genomic Prediction

| Method | Basic Procedure | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Use Cases in Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holdout [3] [5] | Single random split into training and testing sets (e.g., 70%/30%). | • Computational efficiency [6]• Simplicity and ease of implementation [6] | • High variance in performance estimate due to single split [6]• Potentially inefficient use of data [6] | • Initial exploratory analysis with very large datasets [6]• Creating a truly independent validation set for final model assessment [7] |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation [3] | Data partitioned into k equal folds. Iteratively, k-1 folds train the model, and 1 fold tests it. Process repeats k times. | • Reduced bias compared to holdout [4]• All data used for both training and testing [3]• More reliable performance estimate [4] | • Higher computational cost than holdout [7]• Stratification needed for imbalanced data [5] | • Standard for model comparison and hyperparameter tuning [4] [8]• Evaluating genomic prediction models for traits with varying heritability [4] |

| Stratified k-Fold [5] | Enhanced k-fold where each fold preserves the original proportion of target variable classes. | • Handles imbalanced datasets effectively [5]• Prevents folds with missing class representation | • Genomic prediction for case-control studies with unequal group sizes• Classification of disease resistance in plants | |

| Leave-One-Out (LOOCV) [3] | A special case of leave-p-out with p=1. Each single observation serves as the test set once, with the rest as training. | • Virtually unbiased estimate [5]• Uses maximum data for training (n-1 samples) [3] | • Computationally expensive for large n [3] [5]• High variance in estimator [3] | • Small breeding populations or trials with limited samples [5]• Prototyping models with minimal data |

| Leave-p-Out (LpO) [3] | An exhaustive method where all possible training sets are created by leaving out p observations for testing. | • Extremely comprehensive use of data | • Computationally prohibitive for large p and n [3] (e.g., C(100,30) ≈ 3x10^25 combinations [3]) | • Rarely used in genomic prediction due to computational constraints |

| Repeated/Monte Carlo [3] [5] | Repeated random splits of the data into training and testing sets over multiple iterations (e.g., 100-500 times). | • Reduces variability of estimate through averaging [3] | • Computationally intensive• Risk of overlapping samples between training and test sets across iterations | • Providing stable performance estimates for high-value model selection• When the dataset structure doesn't align well with k-fold |

The Holdout Method: Simplicity with Limitations

The holdout method, also known as train-test split or simple validation, is the most fundamental cross-validation approach [3]. It involves randomly splitting the entire dataset into two mutually exclusive subsets: a training set used to build the model and a testing set (or holdout set) used to evaluate its performance [6] [5]. A common partitioning ratio is 70% of data for training and 30% for testing, though this can vary [6].

The primary advantage of the holdout method is its computational efficiency and simplicity, requiring only a single model training cycle [6]. This makes it suitable for initial model building or when working with very large datasets where more complex CV is computationally prohibitive [6]. It is also the only method that can, if implemented with strict data separation, simulate a truly independent test set, which is crucial for assessing a final model's readiness for deployment [7].

However, the holdout approach has significant drawbacks. Its performance estimate can have high variance, meaning it can change substantially depending on which observations are randomly assigned to the training and test sets [6]. This is particularly problematic in genomic studies with limited sample sizes. Furthermore, it is data inefficient, as a portion of the data (the test set) is never used for model training, which can be a critical waste of information in small-scale breeding trials [6].

k-Fold Cross-Validation: The Workhorse for Genomic Model Evaluation

k-Fold cross-validation is arguably the most widely used method for evaluating and tuning genomic prediction models [4] [8]. In this procedure, the dataset is randomly partitioned into k subsets of approximately equal size, known as "folds" [3]. The model is then trained k times, each time using k-1 folds for training and the remaining single fold for validation. The process is repeated until each fold has been used exactly once as the validation set [5]. The final performance metric is typically the average of the k validation results [3].

A key strength of k-fold CV is that it provides a more reliable and less variable estimate of model performance than the holdout method because every observation is used for both training and validation [4]. This makes efficient use of limited data, a common scenario in genomic studies. It is particularly valuable for comparing different prediction models (e.g., G-BLUP vs. BayesA vs. BayesC [4]) and for tuning model hyperparameters without leaking information from the test set into the training process [6].

The value of k is a key choice; common values are 5 or 10 [5]. Lower values (e.g., k=5) are less computationally expensive, while higher values (e.g., k=10) make the training set in each iteration larger and can reduce bias. A special case is Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV), where k equals the number of samples (n) [3]. While LOOCV is nearly unbiased, it is computationally expensive for large n and can have high variance [3]. For imbalanced datasets, Stratified k-fold is recommended, as it ensures each fold has the same proportion of the target variable as the complete dataset [5].

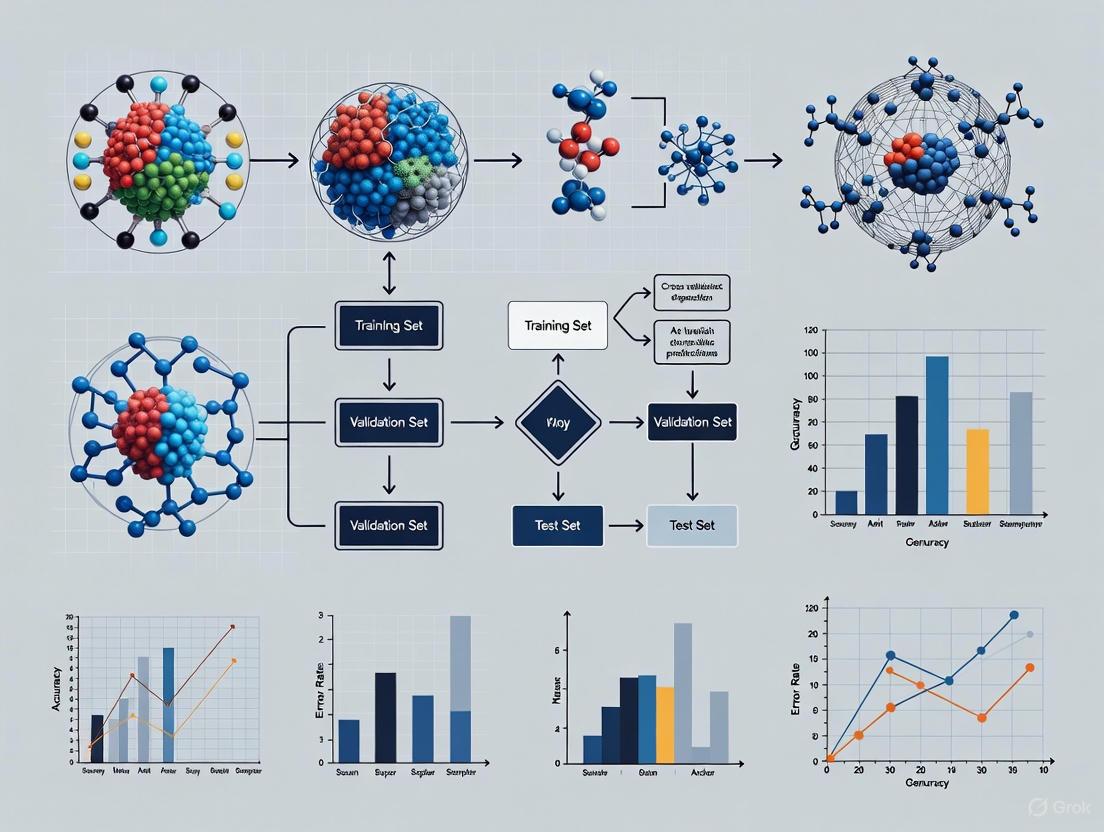

Diagram: Workflow of 5-Fold Cross-Validation

Experimental Protocols: Implementing CV in Genomic Studies

Protocol 1: k-Fold CV for Comparing Genomic Prediction Models

A study comparing the predictive accuracy of various genomic models for crop traits provides a clear protocol for applying k-fold CV in a breeding context [4].

- Objective: To compare the predictive performance of different genomic prediction models (e.g., G-BLUP, BayesA, BayesB, BayesC) and assess the impact of their hyperparameters [4].

- Dataset: Public datasets of wheat (n = 599), rice (n = 1,946), and maize lines with dense marker panels and recorded phenotypes for traits like grain yield [4].

- Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Genotypic data were encoded as allele dosages (0,1,2). Phenotypic data were pre-adjusted for fixed effects (e.g., environments) if necessary.

- Model Definition: Several models from the "Bayesian Alphabet" and mixed linear models (e.g., G-BLUP) were specified [4].

- Cross-Validation: A paired k-fold cross-validation scheme was implemented. The same k-fold partitions were applied to all models to ensure a fair comparison. This "paired" design increases the statistical power to detect differences between models [4].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: For models with hyperparameters (e.g., prior degrees of freedom in BayesA), k-fold CV was used to evaluate different values, selecting the one that optimized predictive accuracy [4].

- Performance Assessment: Predictive accuracy was measured as the correlation between observed and predicted phenotypic values in the validation folds. Statistical tests were proposed to determine if differences in accuracy between models were relevant in the context of expected genetic gain [4].

- Key Findings: The study concluded that k-fold CV is a "generally applicable and statistically powerful methodology to assess differences in model accuracies." It also found that for many models, default hyperparameters or those learned directly from the data (e.g., via REML) were often competitive with extensively tuned values [4].

Protocol 2: Independent Validation for Cross-Generational Prediction

A study on Norway spruce highlights a critical limitation of standard k-fold CV and the need for independent validation in an operational breeding context [2].

- Objective: To assess the accuracy of genomic prediction for wood properties when models are applied across generations and environments, a more realistic breeding scenario [2].

- Dataset: Phenotypic and genomic data from two generations of Norway spruce: parental plus-tree clones (G0) and their progeny (G1) grown in two different trial environments [2].

- Methodology:

- Validation Approaches: Instead of random k-fold splits, the study employed independent validation sets:

- Forward Prediction (Approach A): Models were trained on the parental generation (G0) and used to predict the performance of the progeny generation (G1) in two different environments [2].

- Backward & Across-Environment Prediction (Approaches B & C): Models were trained on one progeny environment to predict the other progeny environment or the parental generation [2].

- Model Fitting: Both pedigree-based (ABLUP) and marker-based (GBLUP) models were fitted [2].

- Performance Metrics: Predictive ability (PA) was measured as the correlation between predicted and observed values, and prediction accuracy (ACC) was calculated by dividing PA by the square root of the trait's heritability [2].

- Validation Approaches: Instead of random k-fold splits, the study employed independent validation sets:

- Key Findings: The study found that while k-fold CV within a single generation can yield optimistic results, forward and backward predictions across generations were feasible for wood density traits but more challenging for growth traits. It emphasized that independent validation "ensuring no individuals were shared between training and validation datasets" is crucial for assessing the real-world utility of genomic prediction models in multi-generational breeding programs [2].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Genomic Prediction Cross-Validation

| Category | Item | Description & Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software & Libraries | R Statistical Environment | Primary platform for implementing custom CV scripts and statistical analyses (e.g., using BGLR, sommer packages) [4] [1]. |

| Python (scikit-learn) | Used for machine learning-based CV workflows, especially with integrated ML and deep learning models [9]. | |

| Specialized Software (SVS) | Commercial software like SNP & Variation Suite (SVS) provides integrated pipelines for genomic prediction (GBLUP, Bayes C) with built-in k-fold cross-validation [8]. | |

| Genomic Prediction Models | G-BLUP / RR-BLUP | A common baseline model using a genomic relationship matrix to model the covariance among genetic effects. Priors assume marker effects follow a normal distribution [4]. |

| Bayesian Alphabet (BayesA, B, C) | A family of models that use different prior distributions (e.g., scaled-t, spike-slab) for marker effects to accommodate various genetic architectures [4]. | |

| Experimental Materials | Plant/Animal Populations | Training populations of known pedigree and phenotype (e.g., wheat, rice, maize lines, Norway spruce pedigrees) for model training [4] [2]. |

| Dense Molecular Marker Panels | Genotyping-by-sequencing or SNP arrays used to obtain genome-wide marker data (e.g., DArT markers, SNPs) for building relationship matrices or feature sets [4] [2]. |

The selection of an appropriate cross-validation method is not a one-size-fits-all decision but a critical strategic choice in genomic prediction research. The holdout method offers simplicity and is useful for creating a truly independent test set or for initial analysis of very large datasets [7] [6]. However, for the more common tasks of model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and reliable performance estimation with limited data, k-fold cross-validation is the recommended and most widely used standard due to its balance of bias, variance, and computational feasibility [4] [3].

For operational breeding programs, where the ultimate goal is to predict the performance of untested individuals in future generations or new environments, the most rigorous approach is independent external validation [2] [10]. While k-fold CV within a single population provides a useful initial benchmark, it can produce optimistically biased estimates of real-world performance. Therefore, the most robust genomic prediction pipelines employ k-fold CV for internal model development and comparison, followed by a final assessment using an independent holdout set or, ideally, a population from a different generation or environment to confirm the model's generalizability and practical utility [2].

Why Cross-Validation is Non-Negotiable in Genomic Prediction

In the two decades since the seminal introduction of genomic selection, the field has witnessed an explosion of statistical models and machine learning algorithms designed to predict complex traits from dense genetic marker panels. For researchers and breeders, this abundance creates a critical question: how does one objectively select the most appropriate model for a specific prediction task? Cross-validation (CV) has emerged as the indispensable methodology for this model evaluation and selection process. By providing a robust framework for estimating how well models will perform on unseen data, CV enables data-driven decisions that directly impact the efficiency of breeding programs and the acceleration of genetic gain. Its proper implementation is not merely a statistical formality but a fundamental requirement for credible genomic prediction.

The Critical Role of Cross-Validation in Genomic Prediction

Fundamental Principles and Importance

Cross-validation is a resampling technique used to evaluate the performance of predictive models by partitioning data into training sets (for model calibration) and testing sets (for model validation). In genomic prediction, this process is crucial because it provides a realistic estimate of a model's ability to generalize to new, unseen genotypes—the ultimate goal in plant and animal breeding programs [11]. By simulating how a model will perform in practice, CV helps prevent overfitting, where a model learns the noise and specifics of the training data rather than the underlying genetic architecture, thus failing to perform well on new data [11] [12].

The non-negotiable status of CV stems from its direct impact on genetic gain. Predictive accuracy estimates obtained through CV directly inform selection decisions, influencing the speed and efficiency of breeding cycles [13]. Without rigorous CV procedures, breeders risk making suboptimal selections based on overly optimistic performance estimates, potentially wasting significant resources and delaying genetic improvement.

Cross-Validation Protocols and Methodologies

Several CV strategies have been developed, each with specific advantages for particular genomic prediction scenarios:

K-Fold Cross-Validation: The dataset is divided into K equal-sized folds. The model is trained on K-1 folds and tested on the remaining fold. This process is repeated K times, with each fold serving as the test set once. The final performance metric is the average across all iterations [11] [12]. This method offers a good balance between bias and computational efficiency.

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV): A special case of K-fold CV where K equals the number of observations in the dataset. In each iteration, a single observation is used for testing and the remaining observations for training [11] [12]. While LOOCV provides nearly unbiased estimates, it is computationally intensive for large datasets.

Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation: Preserves the percentage of samples for each class (or important biological groups) in each fold, which is particularly valuable for imbalanced datasets [11] [14].

Paired K-Fold Cross-Validation: Emphasized in genomic prediction research, this approach ensures that comparisons between candidate models are conducted using the same data partitions, thereby increasing the statistical power to detect meaningful differences in model performance [13].

Nested Cross-Validation: Employed for both model selection and hyperparameter tuning, this approach features two layers of CV: an inner loop for parameter optimization and an outer loop for performance assessment, effectively preventing information leakage and over-optimistic estimates [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Cross-Validation Techniques in Genomic Prediction

| Technique | Best Use Cases | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-Fold CV | Standard genomic prediction scenarios with moderate dataset sizes | Balanced bias-variance tradeoff; computationally efficient | Performance can vary with different random partitions |

| Leave-One-Out CV (LOOCV) | Small datasets where maximizing training data is critical | Low bias; uses maximum data for training | Computationally expensive; high variance in estimates |

| Stratified K-Fold CV | Imbalanced datasets (e.g., case-control studies) | Maintains class distribution; improves estimate reliability | More complex implementation; not for regression tasks |

| Paired K-Fold CV | Comparing multiple models on the same dataset | Enables powerful statistical comparisons between models | Requires careful implementation of identical splits |

| Nested CV | Hyperparameter tuning and model selection | Prevents optimistic bias; robust performance estimates | Computationally intensive; complex implementation |

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying Cross-Validation Impact

Benchmarking Model Performance

The necessity of CV is clearly demonstrated in systematic benchmarking studies. The EasyGeSe resource, which facilitates standardized comparison of genomic prediction methods across multiple species, relies on CV to evaluate performance. In one comprehensive assessment, predictive performance measured by Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) varied significantly by species and trait (p < 0.001), ranging from -0.08 to 0.96 across different datasets, with a mean accuracy of 0.62 [15]. Without standardized CV protocols, such objective comparisons between methods would be impossible.

The same benchmarking revealed modest but statistically significant (p < 1e-10) gains in accuracy for non-parametric methods including random forest (+0.014), LightGBM (+0.021), and XGBoost (+0.025) compared to traditional parametric approaches [15]. These subtle but important differences would be difficult to detect without the statistical power provided by rigorous CV procedures.

Advanced Genomic Prediction Applications

Cross-validation plays an equally critical role in more specialized genomic prediction applications. For genomic predicted cross-performance (GPCP), which predicts the performance of parental combinations rather than individual breeding values, CV is essential for model validation. Studies have demonstrated GPCP's superiority over traditional genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for traits with significant dominance effects, effectively identifying optimal parental combinations and enhancing crossing strategies [1].

In predicting progeny variance—a crucial component for long-term genetic gain—research has shown that predictive ability increases with heritability and progeny size and decreases with QTL number [16]. For instance, in experimental validations using winter bread wheat, parental mean (PM) and usefulness criterion (UC) estimates were significantly correlated with observed values for all traits studied (yield, grain protein content, plant height, and heading date), while standard deviation (SD) was correlated only for heading date and plant height [16]. These nuanced insights into model performance across different trait architectures depend entirely on robust CV frameworks.

Table 2: Cross-Validation Performance Across Genomic Prediction Applications

| Application | Trait/Species | Key Finding | Impact of Proper CV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Benchmarking [15] | Multiple species (barley, maize, rice, wheat, etc.) | Significant variation in predictive performance across species and traits (r: -0.08 to 0.96) | Enabled fair comparison of 10+ prediction methods across diverse biological contexts |

| GPCP for Cross Performance [1] | Yam (clonal crop) | Superior to GEBV for traits with significant dominance effects | Validated new tool for identifying optimal parental combinations |

| Progeny Variance Prediction [16] | Winter bread wheat (yield, quality traits) | SD predictions required large progenies and were trait-dependent | Identified limitations for complex traits, guiding appropriate method application |

| Multi-Environment Trials [17] | Rye (grain yield) | Spatial models with row/column effects yielded highest predictive ability | Optimized phenotypic data analysis for genomic prediction |

Implementation Protocols and Computational Considerations

Standardized Experimental Workflows

Implementing CV in genomic prediction requires careful experimental design. The following workflow illustrates a standard k-fold cross-validation process:

Computational Innovations

A significant innovation in genomic prediction CV addresses the computational burden, particularly for complex Bayesian models and large datasets. Research has demonstrated that it is feasible to obtain exact CV results without model retraining for many linear models, including ridge regression, GBLUP, and reproducing kernel Hilbert spaces regression [18]. For Bayesian models, importance sampling techniques can produce CV results using a single Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) run, dramatically reducing computational requirements [18].

These computational advances make extensive CV feasible even for resource-constrained breeding programs, removing a significant barrier to proper model evaluation. The ability to conduct powerful CV without prohibitive computation time reinforces its non-negotiable status in genomic prediction.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Prediction Cross-Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| BGLR R Package [13] | Bayesian regression models with various priors | Fitting Bayesian alphabet models (BayesA, BayesB, BayesC) |

| Sommer R Package [1] | Mixed model analysis | Fitting mixed linear models with additive and dominance relationship matrices |

| Scikit-Learn [12] [14] | Machine learning and cross-validation | Implementing k-fold CV, stratified CV, and nested CV |

| AlphaSimR [1] | Breeding program simulations | Generating synthetic datasets for method validation |

| EasyGeSe [15] | Benchmarking dataset collection | Standardized comparison of genomic prediction methods |

| BreedBase [1] | Breeding database management | Implementing genomic predicted cross-performance (GPCP) tool |

Cross-validation represents the cornerstone of reliable genomic prediction. Its non-negotiable status is rooted in both theoretical principles and empirical evidence across countless studies. Through rigorous CV, researchers can objectively compare competing models, optimize hyperparameters, estimate true predictive accuracy, and ultimately make informed decisions that accelerate genetic gain. As genomic prediction continues to evolve with increasingly complex models and larger datasets, the proper implementation of cross-validation will remain essential for translating genetic data into meaningful breeding progress.

Genomic prediction has revolutionized breeding and genetic research by enabling the selection of individuals based on their genetic potential. However, the reliability of these predictions hinges on effectively addressing three core challenges: overfitting, selection bias, and limited generalizability. Overfitting occurs when models capture noise instead of true biological signals, leading to impressive performance on training data that fails to translate to new populations. Selection bias emerges from non-random sampling in training populations, while generalizability limitations arise when models trained on one population perform poorly on genetically distinct groups.

Cross-validation has emerged as the cornerstone methodology for detecting these issues, providing a framework for robust model evaluation and comparison. This guide objectively compares the performance of mainstream genomic prediction models—from traditional GBLUP to advanced machine learning approaches—in addressing these critical challenges, supported by experimental data from recent studies.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Genomic Prediction Models

The table below summarizes the predictive performance of different genomic prediction models across multiple species and traits, as reported in recent benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Comparative performance of genomic prediction models across diverse species

| Model Category | Specific Models | Average Accuracy Range | Performance Notes | Computational Efficiency | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Mixed Models | GBLUP, rrBLUP | 0.62-0.755 | Most balanced performance; robust across traits | Highest - Fastest computation, minimal tuning | [19] [20] [21] |

| Bayesian Methods | BayesA, BayesBÏ€, BayesCÏ€, BayesR | 0.622-0.755 | Highest accuracy for some polygenic traits | Low - Computationally intensive, slow convergence | [22] [19] [4] |

| Machine Learning | RF, SVR, XGBoost, KRR | 0.62-0.755 | Competitive for complex, non-linear traits | Variable - RF/XGBoost faster than Bayesian; SVR slower | [19] [20] [21] |

| Deep Learning | MLP, CropARNet, DNNGP | 0.62-0.741 | Excels with large datasets and complex architectures | Lowest - Requires significant resources and tuning | [20] [23] |

Table 2: Model performance across trait architectures and data scenarios

| Scenario | Recommended Model | Accuracy Advantage | Risk Considerations | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Heritability Traits | GBLUP, BayesCÏ€ | All models perform similarly | ML models show no significant advantage | [19] [21] |

| Low Heritability/Complex Traits | Deep Learning, Bayesian Methods | +1.1-3.0% over GBLUP | High overfitting risk with small sample sizes | [19] [20] [23] |

| Small Sample Sizes (<500) | GBLUP, Bayesian LASSO | More stable predictions | Deep learning severely overfits | [20] [24] |

| Large Sample Sizes (>5,000) | Deep Learning, Bayesian Methods | +2.2-3.0% over GBLUP | Computational constraints become limiting | [19] [20] |

| Across-Generation Prediction | GBLUP with relationship matrices | More stable than complex models | All models show accuracy decay | [2] [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Evaluation

Standard Cross-Validation Framework

Robust evaluation of genomic prediction models requires systematic cross-validation protocols that directly address overfitting and generalizability concerns. The most widely adopted approach involves k-fold cross-validation with independent validation sets to simulate real-world prediction scenarios [4]. In this framework, the available data is partitioned into k subsets (typically k=5 or k=10), with k-1 folds used for model training and the remaining fold used for validation. This process is repeated until all folds have served as the validation set, and the predictive performance is averaged across all iterations [4].

For assessing generalizability across generations or environments, forward prediction protocols are essential, where models are trained on earlier generations (e.g., parental lines) and validated on subsequent generations (e.g., progeny) [2]. This approach was effectively implemented in a Norway spruce study that trained models on parental generation (G0) plus-trees and validated on progeny (G1) across two different environments, Höreda (G1H) and Erikstorp (G1E) [2]. This design directly tests model performance against genetic recombination and generation turnover, providing a realistic assessment of practical utility.

Benchmarking Study Designs

Large-scale benchmarking studies provide the most reliable evidence for model performance comparisons. The EasyGeSe initiative has established a standardized framework for such evaluations across multiple species, including barley, maize, rice, wheat, and livestock species [15]. Their protocol involves:

- Curated Datasets: Collecting and standardizing datasets from diverse species and traits to enable fair comparisons [15].

- Uniform Evaluation: Applying the same cross-validation splits and performance metrics (Pearson's correlation) across all models [15].

- Computational Assessment: Tracking both predictive accuracy and resource requirements (computation time, memory usage) [15].

Another comprehensive evaluation compared GBLUP, Bayesian methods, and machine learning models on 14 real-world plant breeding datasets representing different genetic architectures, population sizes, and marker densities [20]. This study employed careful hyperparameter tuning for each model and dataset combination, followed by five-fold cross-validation with five repetitions to ensure statistical reliability of the accuracy estimates [20].

Diagram: Experimental workflow for robust genomic prediction model evaluation

Addressing Core Challenges

Overfitting: Model Complexity versus Data Structure

Overfitting represents the most persistent challenge in genomic prediction, particularly with complex models applied to high-dimensional genomic data. The relationship between model complexity, dataset size, and overfitting risk follows a consistent pattern across studies.

Deep learning models demonstrate remarkable capacity to capture non-linear relationships and epistatic interactions, but this strength becomes a liability with limited training data. In the comprehensive plant breeding study, deep learning models frequently provided superior predictive performance compared to GBLUP, particularly in smaller datasets, but this advantage was highly dependent on careful parameter optimization [20]. Without extensive hyperparameter tuning, these complex models consistently underperformed due to overfitting.

GBLUP provides inherent protection against overfitting through its simplifying assumptions. By treating all markers as equally contributing to genetic variance, GBLUP avoids the overparameterization that plagues more flexible models [19]. This makes GBLUP particularly valuable when working with limited sample sizes. In canine breeding studies, GBLUP's performance was statistically indistinguishable from more complex machine learning models across traits with varying heritabilities, suggesting that its simplicity provides a favorable bias-variance tradeoff in many practical scenarios [21].

Bayesian methods occupy a middle ground, offering more flexibility than GBLUP while incorporating regularization through their prior distributions. Models like BayesBÏ€ and BayesCÏ€ include spike-slab priors that assume only a subset of markers have nonzero effects, effectively performing feature selection during model fitting [4]. This approach can improve accuracy while mitigating overfitting, as demonstrated in Holstein cattle where BayesR achieved the highest average prediction accuracy among all tested methods [19].

Selection Bias: Training Population Composition and Genetic Architecture

Selection bias occurs when training populations non-representatively sample the target genetic diversity, leading to systematically skewed predictions. This challenge manifests differently across breeding contexts.

In crop breeding, selection bias often arises from convenience sampling of elite breeding lines that overrepresent favorable alleles. The genomic predicted cross-performance (GPCP) tool addresses this by explicitly modeling both additive and dominance effects, allowing breeders to identify optimal parental combinations that might be overlooked by models focusing solely on additive breeding values [1]. For traits with significant dominance effects, GPCP outperformed traditional genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) by effectively identifying heterosis potential in parental combinations [1].

In forest tree breeding, where generations span decades, selection bias can result from environmental differences between training and validation populations. The Norway spruce study addressed this through across-environment predictions, where models trained in one location (Höreda) were validated in another (Erikstorp) [2]. The results showed that while wood properties maintained reasonable prediction accuracy across environments, growth traits exhibited significant genotype-by-environment interactions, highlighting the need for environment-specific models when such interactions are pronounced [2].

Weighted GBLUP (WGBLUP) approaches can mitigate selection bias by incorporating prior biological knowledge. By assigning higher weights to markers likely to be functionally important, these models can improve signal detection within biased training populations. In simulated livestock populations, WGBLUP accuracy increased as included quantitative trait loci (QTL) explained up to 80% of genetic variance, after which accuracy declined due to the inclusion of uninformative markers [24].

Generalizability: Across-Generation and Cross-Species Performance

Generalizability remains the most challenging hurdle for genomic prediction models, with performance typically decaying as genetic distance increases between training and target populations.

Across-generation predictions systematically demonstrate this decay, though the magnitude varies by trait architecture. In Norway spruce, forward prediction (training on parents, predicting progeny) achieved reasonable accuracy for wood density and tracheid properties but proved challenging for growth and low-heritability traits [2]. This pattern reflects the more polygenic architecture of growth traits, where linkage disequilibrium between markers and causal variants is more susceptible to breakdown through recombination.

Cross-population predictions face even greater challenges. The EasyGeSe benchmarking initiative revealed that predictive performance varied significantly by species and trait, with correlations ranging from -0.08 to 0.96 across diverse organisms [15]. This extreme variation highlights the fundamental limitation of genomic prediction: models capture patterns of linkage disequilibrium specific to particular populations, and these patterns are not conserved across genetically distinct groups.

Bayesian models have demonstrated relatively better generalizability in some contexts, particularly for traits with major effect genes. In Holstein cattle, BayesR achieved the highest predictive accuracy across multiple traits, suggesting that its flexible effect distribution can better capture the underlying genetic architecture across different subsets of the population [19]. However, no model completely overcomes the fundamental biological constraints on generalizability imposed by population-specific linkage disequilibrium patterns.

Diagram: Model selection workflow for balancing performance and generalizability

Table 3: Essential research tools and resources for genomic prediction studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R/BGLR, R/sommer, Python | Model implementation and fitting | Universal for all genomic prediction studies [1] [4] |

| Genomic Relationship | G-matrix, A-matrix | Quantifying genetic relationships | GBLUP, population structure analysis [2] [19] |

| Benchmarking Platforms | EasyGeSe | Standardized model evaluation | Cross-species model validation [15] |

| Simulation Tools | AlphaSimR, QMSim | Generating synthetic genomes | Method development and testing [1] [24] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | CropARNet, DNNGP | Non-linear pattern detection | Complex trait prediction [20] [23] |

| Cross-validation | k-fold, forward prediction | Model validation | Assessing overfitting and generalizability [2] [4] |

The comparative analysis of genomic prediction models reveals a consistent trade-off between predictive potential and robustness. While advanced machine learning and deep learning models can achieve superior accuracy for complex traits in large datasets, they require extensive tuning and computational resources while remaining vulnerable to overfitting. GBLUP maintains its position as a robust, computationally efficient baseline that performs consistently across diverse scenarios. Bayesian methods offer a promising middle ground, particularly when prior biological knowledge can be incorporated.

The optimal model selection depends critically on the specific research context: dataset size, trait complexity, genetic architecture, and computational resources. For most practical applications, GBLUP provides the best balance of performance, interpretability, and computational efficiency. As the field progresses toward Breeding 4.0, integrating biological knowledge into flexible modeling frameworks like weighted GBLUP and Bayesian methods appears most likely to deliver sustainable improvements in genomic prediction while maintaining generalizability across generations and environments.

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff in Model Evaluation

In the field of genomic selection, where models predict complex traits from dense molecular marker data, the bias-variance tradeoff is not merely a theoretical concept but a practical consideration directly impacting genetic gain and breeding efficiency [13]. Genomic prediction models essentially relate genotypic variation to phenotypic variation, and practitioners must navigate numerous modeling decisions where optimizing this tradeoff becomes paramount for predictive accuracy [13] [4]. The challenge is particularly acute in genomic applications where the number of markers (p) typically far exceeds the number of genotypes (n), creating inherent over-parameterization that must be managed through appropriate regularization techniques [13]. This guide examines how the bias-variance tradeoff manifests across different genomic prediction approaches, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers and breeding professionals.

Theoretical Framework: Decomposing Prediction Error

Fundamental Concepts

- Bias: Error from simplifying real-world complexity when a model cannot capture the underlying patterns in data. High-bias models oversimplify and typically underfit, showing poor performance on both training and testing data [25] [26] [27].

- Variance: Error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set. High-variance models overfit to training data noise, showing excellent training performance but poor generalization to unseen data [25] [26].

- Mathematical Decomposition: The expected prediction error can be decomposed as:

Error = Bias² + Variance + Irreducible Error[27]. This relationship underscores that reducing one component often increases the other, creating the essential "tradeoff" [28].

The Tradeoff in Model Complexity

The relationship between model complexity, bias, and variance follows a predictable pattern visualized below:

Visualization of how bias decreases while variance increases with model complexity, creating a U-shaped total error curve with an optimal balance point [25] [28] [27].

Comparative Analysis of Genomic Prediction Models

Model Families in Genomic Selection

Genomic prediction methods fall into three main categories with distinct bias-variance characteristics [15]:

- Parametric Methods: Include GBLUP and Bayesian models (BayesA, BayesB, BayesC, Bayesian Lasso). These explicitly assume distributions for marker effects and typically demonstrate moderate bias and variance [13] [15].

- Semi-Parametric Methods: Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces (RKHS) uses kernel functions to model complex relationships with flexible bias-variance profiles depending on kernel choice [15].

- Non-Parametric Methods: Machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machines) typically have lower bias but higher variance, especially with limited training data [15].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent benchmarking across multiple species provides empirical evidence of how different model families perform in practical genomic selection scenarios:

Table 1: Genomic Prediction Performance Across Model Families and Species [15]

| Species | Trait | GBLUP | BayesA | RKHS | Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley | Disease Resistance | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.71 |

| Common Bean | Days to Flowering | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| Maize | Grain Yield | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| Rice | Plant Height | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

| Wheat | Grain Quality | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.73 |

| Average Accuracy | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.70 |

The data reveals modest but consistent accuracy improvements from non-parametric methods, with XGBoost showing approximately 0.025 higher correlation coefficients on average compared to GBLUP, though these gains must be weighed against increased complexity and potential variance [15].

Bias-Variance Profiles by Model Type

Table 2: Bias-Variance Characteristics of Genomic Prediction Models

| Model | Bias Tendency | Variance Tendency | Best Application Context | Regularization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBLUP | Moderate-High | Low | Traits with additive architecture | Genetic relationship matrix |

| BayesA | Moderate | Moderate | Traits with some large-effect QTL | Heavy-tailed priors on markers |

| BayesB | Moderate | Moderate | Sparse genetic architectures | Spike-slab priors |

| Bayesian Lasso | Moderate | Low-Moderate | Polygenic traits | L1 regularization |

| RKHS | Low-Moderate | Moderate-High | Non-additive genetic effects | Kernel bandwidth tuning |

| Random Forest | Low | High | Complex trait architectures | Tree depth, sample bootstrapping |

| XGBoost | Low | High | Large datasets with complex patterns | Learning rate, tree constraints |

The Bayesian alphabet models specifically address the "n ≪ p" problem in genomics through their prior distributions, which act as regularization devices to balance the bias-variance tradeoff [13]. For instance, BayesB uses spike-slab priors that assume many markers have zero effect, making it suitable for traits with sparse genetic architectures [13].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluation

Cross-Validation in Genomic Studies

Proper evaluation of the bias-variance tradeoff in genomic prediction requires robust cross-validation protocols. The standard approach in plant breeding applications involves:

Paired k-Fold Cross-Validation [13] [4]:

- Data Partitioning: Randomly divide the genotype and phenotype data into k folds (typically k=5 or k=10)

- Iterative Training/Testing: For each iteration, use k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for testing

- Paired Comparisons: Ensure identical folds when comparing different models to reduce variability in accuracy estimates

- Performance Aggregation: Calculate average prediction accuracy across all folds

The visualization below illustrates this process:

K-fold cross-validation workflow for genomic prediction models, ensuring reliable estimation of generalization error [13] [25].

Multi-Omics Integration Protocols

Recent advances incorporate multiple omics layers to improve prediction accuracy. A 2025 study evaluated 24 integration strategies combining genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics using this protocol [29]:

- Data Collection: Acquire matched genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic profiles for breeding populations

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize each omics layer separately, handle missing values, and perform quality control

- Integration Approaches:

- Early Fusion: Concatenate features from multiple omics layers before model training

- Model-Based Integration: Use hierarchical models or kernel methods to combine omics layers while preserving their unique structures

- Validation: Employ cross-validation within the training set to tune hyperparameters, then evaluate on held-out test sets

This study found that model-based integration approaches consistently outperformed genomic-only models, particularly for complex traits, while simple concatenation methods often underperformed due to increased variance without corresponding bias reduction [29].

Table 3: Key Resources for Genomic Prediction Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R/BGLR [13], Python/scikit-learn [25] | Implement genomic prediction models with cross-validation | General model development and evaluation |

| Benchmarking Platforms | EasyGeSe [15] | Standardized datasets for comparing prediction methods | Method benchmarking across species |

| Genomic Relationship | G-matrices [13] [4], E-GBLUP [13] | Model covariance among genetic values | GBLUP and related mixed models |

| Bayesian Priors | Bayesian Alphabet [13] [4] | Regularize marker effects in high-dimensional settings | BayesA, BayesB, BayesC models |

| Machine Learning | XGBoost [15], Random Forest [15] | Capture complex non-linear relationships | Non-parametric prediction |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Early fusion, Model-based fusion [29] | Combine complementary biological data layers | Enhanced prediction for complex traits |

The bias-variance tradeoff represents a fundamental consideration in genomic prediction model selection. While non-parametric machine learning methods show modest accuracy improvements in benchmarking studies [15], their increased complexity and potential variance may not justify the gains in all breeding contexts. The optimal model choice depends on trait architecture, training population size, and computational resources.

Future directions point toward sophisticated multi-omics integration approaches that strategically balance bias and variance through model-based data fusion [29], potentially moving beyond simple tradeoffs to genuine improvements in predictive performance. As genomic selection continues to evolve, the deliberate management of the bias-variance relationship remains essential for maximizing genetic gain in crop and livestock breeding programs.

Implementing Core Cross-Validation Techniques in Genomic Studies

In genomic selection (GS), the primary goal is to predict complex traits using dense molecular marker information, enabling the selection of superior genotypes without direct phenotypic selection [9]. The accuracy of these genomic prediction (GP) models determines the speed of genetic gain, making robust model assessment critical for breeding programs. Genomic prediction presents unique challenges for model validation, including often limited population sizes, high-dimensional data, and complex trait architectures influenced by additive and dominance effects [1]. In this context, k-fold cross-validation has emerged as a foundational methodology for obtaining realistic performance estimates and guiding model selection.

Understanding k-Fold Cross-Validation

The Core Methodology

K-fold cross-validation (k-fold CV) is a resampling technique that assesses how a predictive model will generalize to an independent dataset [30] [31]. The standard procedure involves:

- Random Partitioning: The dataset is randomly divided into k approximately equal-sized subsets (folds).

- Iterative Training and Validation: For each of the k iterations, one fold is held out as the validation set, while the remaining k-1 folds are used to train the model.

- Performance Averaging: The model's performance metric (e.g., prediction accuracy) is calculated for each validation fold. The final performance estimate is the average of the k individual metrics [32] [33].

This process is illustrated in the following workflow:

Purpose in the Model Development Workflow

It is crucial to distinguish between model assessment and model building. K-fold CV is primarily used for model assessment—evaluating how well a given modeling procedure (including data preprocessing, algorithm choice, and hyperparameters) will perform on unseen data [34]. The k individual models trained during cross-validation (surrogate models) are typically discarded after evaluation. The final production model is then trained on the entire dataset using the procedure validated as best [34].

Comparative Analysis of Model Validation Techniques

k-Fold Cross-Valdiation vs. Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation

Leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) is a special case of k-fold CV where k equals the number of samples in the dataset (n) [35] [31]. While related, these techniques have distinct characteristics and applications, particularly in genomic prediction contexts with typically small to moderate sample sizes.

Table 1: Comparison of k-Fold Cross-Validation and Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation

| Aspect | k-Fold Cross-Validation | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Splits data into k subsets (folds); each fold serves as validation once [30]. | Uses a single observation as validation and the rest for training; repeated n times [35]. |

| Bias | Tends to have higher pessimistic bias, especially with small k, as training sets are smaller [35]. | Approximately unbiased because training sets use n-1 samples [35]. |

| Variance | Generally has lower variance due to less correlation between performance estimates [35]. | Higher variance because performance estimates are highly correlated [35]. |

| Computational Cost | Trains k models (typically 5-10); feasible for large datasets [31]. | Trains n models; prohibitive for large datasets [35] [31]. |

| Recommended Use Case | Large datasets; computationally intensive models; standard practice in genomic prediction [32] [31]. | Very small datasets where maximizing training data is critical [35] [31]. |

k-Fold Cross-Validation vs. Bootstrapping

Bootstrapping is another resampling technique that involves repeatedly drawing samples with replacement from the original dataset [30].

Table 2: Comparison of k-Fold Cross-Validation and Bootstrapping

| Aspect | k-Fold Cross-Validation | Bootstrapping |

|---|---|---|

| Data Partitioning | Mutually exclusive folds; no overlap between training and test sets in any iteration [30]. | Samples with replacement; creates bootstrap samples that may contain duplicates [30]. |

| Primary Purpose | Estimate model performance and generalize to unseen data [30]. | Estimate the variability of a statistic or model performance [30]. |

| Bias-Variance Trade-off | Better balance between bias and variance for performance estimation [30]. | Can provide lower bias but may have higher variance [30]. |

| Advantages | Reduces overfitting by validating on unseen data; helps in model selection and tuning [30] [6]. | Captures uncertainty in model estimates; useful for small datasets or unknown distributions [30]. |

| Disadvantages | Computationally intensive for large k or datasets [30]. | May overestimate performance due to sample similarity [30]. |

Experimental Evidence in Genomic Prediction

Validation in Genomic Predicted Cross-Performance Tool Development

A 2025 study implementing the Genomic Predicted Cross-Performance (GPCP) tool provides a relevant example of k-fold CV in action. Researchers used simulated datasets of varying sizes (N = 250, 500, 750, and 1000 individuals) with 18 chromosomes and 56 quantitative trait loci (QTLs) to evaluate prediction accuracy [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset: Four founder populations with distinct dominance architectures simulated using AlphaSimR package [1].

- Traits: Five uncorrelated trait scenarios with varying dominance effects (mean DD: 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4) [1].

- Breeding Pipeline: Multi-stage clonal evaluation reflecting typical breeding practice [1].

- Validation: K-fold cross-validation applied to compare GEBV and GPCP methods over 40 selection cycles [1].

- Metrics: Useful criterion (UC) and mean heterozygosity (H) tracked per cycle to quantify genetic gain and diversity maintenance [1].

Key Finding: GPCP demonstrated superiority over traditional genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for traits with significant dominance effects, effectively identifying optimal parental combinations and enhancing crossing strategies [1].

Evidence from Financial Risk Prediction

A 2025 study on bankruptcy prediction provides external validation of k-fold CV's effectiveness. The research employed a nested cross-validation framework to assess the relationship between CV and out-of-sample (OOS) performance across 40 different train/test data partitions [32].

Key Results:

- K-fold cross-validation was found to be a valid selection technique when applied within a model class on average [32].

- However, for specific train/test splits, k-fold CV may fail to select the best-performing model, with 67% of model selection regret variability explained by the particular train/test split [32].

- The study highlighted that large values of k may overfit the test fold for XGBoost models, leading to improvements in CV performance with no corresponding gains in OOS performance [32].

Implementation Guidelines for Genomic Prediction

Selecting the Appropriate k Value

The choice of k represents a trade-off between computational expense and estimation accuracy. Common practices in genomic prediction include:

- k=5 or k=10: Most frequently used values, providing a good balance between bias and variance [32] [6].

- Small k (e.g., 5): Results in higher bias but lower variance and computational cost [35].

- Large k (e.g., 10 or more): Reduces bias but increases variance and computational requirements [35].

- Stratified k-fold: Recommended for imbalanced datasets to maintain class distribution in each fold [30].

Recent evidence suggests that very large k values (approaching LOOCV) may overfit the test fold for certain algorithms, providing misleading performance estimates [32].

Special Considerations for Multi-Omics Integration

With the emergence of multi-omics integration in genomic prediction, proper validation becomes increasingly critical. A 2025 study evaluating 24 integration strategies combining genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics highlights these challenges [9].

Key Considerations:

- Data Dimensionality: Multi-omics datasets present significant heterogeneity in dimensionality, measurement scales, and noise levels across platforms [9].

- Model Complexity: Advanced machine learning approaches required to capture non-additive, nonlinear, and hierarchical interactions across omics layers necessitate robust validation [9].

- Standardized Protocols: The implementation of standardized cross-validation procedures is essential for benchmarking across model types and ensuring reproducible results [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Genomic Prediction Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaSimR | Individual-based simulation of breeding programs; generates synthetic genomes with predefined genetic architecture [1]. | Creating simulated datasets for method validation and power analysis. |

| BreedBase | Integrated breeding platform; hosts implementation of GPCP tool for predicting cross-performance [1]. | Managing crossing strategies and predicting parental combinations in breeding programs. |

| Sommer R Package | Fitting mixed linear models using Best Linear Unbiased Predictions (BLUPs); handles additive and dominance relationship matrices [1]. | Genomic prediction model fitting with complex variance-covariance structures. |

| Ranger R Package | Efficient implementation of random forests for high-dimensional data [32]. | Benchmarking machine learning approaches for genomic prediction. |

| XGBoost | Gradient boosting framework with optimized implementation and built-in cross-validation [32]. | State-of-the-art tree-based modeling for complex trait prediction. |

| 2-Phenylhexan-3-one | 2-Phenylhexan-3-one, CAS:646516-86-1, MF:C12H16O, MW:176.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Chlorooctadecylsilane | Chlorooctadecylsilane, CAS:86949-75-9, MF:C18H37ClSi, MW:317.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Validation Frameworks

Nested Cross-Validation for Hyperparameter Tuning

For comprehensive model selection that includes hyperparameter optimization, nested (or double) cross-validation provides a more robust framework:

Leave-Source-Out Validation for Multi-Source Data

When dealing with data from multiple sources (e.g., different research institutions, breeding locations), leave-source-out cross-validation provides more realistic generalization estimates [36]. A 2025 study on cardiovascular disease classification found that standard k-fold CV systematically overestimates prediction performance when the goal is generalization to new sources, while leave-source-out CV provides more reliable performance estimates, though with greater variability [36].

K-fold cross-validation represents the industry standard for model assessment in genomic prediction due to its balanced approach to bias-variance trade-offs, computational feasibility, and proven effectiveness across diverse breeding scenarios. While alternatives like LOOCV offer lower bias for small datasets and bootstrapping provides robust variance estimation, k-fold CV strikes the optimal balance for most practical applications in genomic selection.

The evidence from recent genomic studies confirms that when properly implemented with appropriate k values and consideration for dataset structure, k-fold CV delivers reliable performance estimates that guide effective model selection. As genomic prediction evolves to incorporate multi-omics data and more complex modeling approaches, robust validation methodologies like k-fold CV will remain foundational to ensuring accurate, reproducible, and biologically meaningful predictions that accelerate genetic gain in breeding programs.

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) represents a special case of k-fold cross-validation where k equals the number of observations (n) in the dataset. Within genomic prediction models, LOOCV is particularly valued for its nearly unbiased estimation of predictive performance, making it a benchmark method for model assessment in fields with limited sample sizes, such as animal breeding and plant genomics. This guide provides an objective comparison of LOOCV against alternatives like k-fold cross-validation, detailing its operational mechanisms, advantages, disadvantages, and optimal use cases, supported by experimental data and tailored for research applications in genomics and drug development.

Cross-validation is a fundamental model assessment technique used to estimate how a statistical model will generalize to an independent dataset, crucial for preventing overfitting and selection bias [3]. In genomic selection, which leverages genome-wide marker data to predict complex traits, cross-validation is indispensable for evaluating the predictive ability of models before deploying them in breeding programs or clinical settings [4]. LOOCV is an exhaustive cross-validation method wherein the model is trained on all data points except one, which is used for validation; this process is repeated n times until each observation has served as the test set once [3]. The final performance metric, such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression, is the average of all n iterations [37]. Its mathematical formulation is:

[\textrm{MSE}{LOOCV} = \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^N (yi - \hat{y}i)^2]

where ( \hat{y}_i ) is the prediction for the i-th observation when it is left out of the training process [37]. In the context of genomic best linear unbiased prediction (GBLUP) and other genomic models, LOOCV provides a robust framework for quantifying the accuracy of breeding value predictions [38] [39].

How LOOCV Works: A Detailed Workflow

The LOOCV process is methodical, ensuring each data point contributes to validation. The workflow below illustrates the iterative process of LOOCV, which is particularly useful for understanding model stability in genomic applications.

Figure 1: The LOOCV Iterative Process. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps in leave-one-out cross-validation, where each data point is sequentially used as a validation set.

Experimental Protocol for Genomic Prediction Models

Implementing LOOCV in genomic prediction studies, such as those employing GBLUP or Bayesian models, follows a specific protocol:

- Data Preparation: Obtain a genotype matrix (e.g., SNPs) and a phenotype vector for

nindividuals. Pre-correct phenotypes for fixed effects like population structure or environment if necessary [38] [39]. - Model Definition: Specify the genomic model. For example:

- Efficient Computation: A naive approach of refitting the model

ntimes is computationally prohibitive. Efficient strategies leverage matrix identities to avoid repeated model fitting.- For MEM when

n ≥ p, the prediction residual for thej-th observation can be computed directly as: [ \hat{ej} = \frac{yj - \boldsymbol{x}^{\prime}{j}\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}^{}}}{1 - H{jj}} ] whereH_jjis thej-th diagonal element of the hat matrixH = X*(X*'X* + Dλ)â»Â¹X*'[38] [39]. This leverages the fact that the model needs to be fit only once to the entire dataset to obtain all LOOCV residuals. - Similarly, for BVM when

p ≥ n, an efficient strategy exists where: [ \hat{ej} = \frac{yj - \boldsymbol{z}^{\prime}{j}\hat{\boldsymbol{u}^{}}}{1 - C{jj}} ] whereC_jjis thej-th diagonal element ofC = Z*(Z*'Z* + Gλ)â»Â¹Z*'[38] [39].

- For MEM when

- Performance Evaluation: Calculate the final LOOCV metric. The most common is the Predicted Residual Sum of Squares (PRESS):

PRESS = Σ(ê_j)². Predictive accuracy is often reported as the correlation between the predicted valuesŷ_j = y_j - ê_jand the observed valuesy_j[38] [39].

Advantages and Disadvantages of LOOCV

LOOCV offers distinct benefits and drawbacks compared to other cross-validation methods, which are summarized in the table below and detailed thereafter.

Table 1: Pros and Cons of LOOCV

| Aspect | Advantages of LOOCV | Disadvantages of LOOCV |

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Very Low: Nearly unbiased estimate of test error, as training set size (n-1) is almost the full dataset [35] [40]. | N/A |

| Variance | N/A | High: Estimates can have high variance because training sets are extremely similar across folds, leading to correlated error estimates [35] [41]. |

| Data Usage | Maximized: Uses every data point for both training and validation, ideal for scarce data [42]. | N/A |

| Computational Cost | N/A | Very High: Naively requires n model fits. Though efficient shortcuts exist for some models (e.g., linear regression, GBLUP) [38] [39] [37]. |

| Result Stability | Deterministic: Produces a unique, non-random result for a given dataset [40]. | N/A |

Key Advantages

- Minimized Bias: The primary advantage of LOOCV is that it produces an almost unbiased estimate of the test error. Since each training set uses

n-1observations—virtually the entire dataset—the performance estimate closely approximates what would be obtained from training on the entire available data [35] [40]. This is particularly valuable in genomic studies where sample sizes are often limited due to the high cost of phenotyping. - Maximized Data Efficiency: LOOCV is ideal for small datasets because it reserves only one sample for testing, allowing the model to learn from the maximum amount of data available [42]. This avoids the problem of the validation set approach, which can overestimate the test error by training on a significantly smaller subset [37].

Key Disadvantages

- High Computational Cost: The most cited drawback is computational expense. A naive implementation requires fitting the model

ntimes, which is prohibitive for largenor complex models [12] [41]. However, as shown in genomic prediction, efficient computational strategies can reduce this cost dramatically—by a factor of 99 to 786 times for datasets with 1,000 observations [38] [39]. - High Variance: The LOOCV estimate can have high variance. Because the

ntraining sets overlap significantly, the resulting prediction errors are highly correlated. Averaging these correlated errors can lead to a higher variance in the final performance estimate compared to k-fold CV with a smallerk[35]. This is critical in scenarios where model performance needs to be stable across different data samples.

LOOCV vs. k-Fold Cross-Validation: A Quantitative Comparison

The choice between LOOCV and k-fold cross-validation involves a direct trade-off between bias and variance. The table below synthesizes experimental comparisons from the literature, highlighting their performance differences.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of LOOCV and k-Fold Cross-Validation

| Study / Context | Metric | LOOCV Performance | k-Fold (k=10) Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Model Evaluation [35] [41] | Bias | Very Low | Slightly Higher | k-fold trains on a smaller (~90%) sample, mildly overestimating test error. |

| General Model Evaluation [35] [41] | Variance | Higher | Lower | Fewer folds in k-fold reduce correlation between training sets, lowering variance. |

| Imbalanced Data (RF, Bagging) [41] | Sensitivity | 0.787, 0.784 | Up to 0.784 (RF) | LOOCV achieved high sensitivity but with lower precision and higher variance. |

| Balanced Data (SVM) [41] | Sensitivity | 0.893 | Not Reported | With parameter tuning, LOOCV can achieve high performance. |

| Computational Efficiency [41] | Processing Time | High | Efficient (e.g., SVM: 21.48s) | k-fold is significantly faster, especially for large n or complex models. |

The Bias-Variance Trade-off in Practice

The core trade-off is statistical, not just computational. LOOCV is low-bias but high-variance, while k-fold CV (especially with k=5 or 10) is slightly higher-bias but lower-variance [35]. For small datasets (n < 1000), the reduction in bias from LOOCV often outweighs the increase in variance. For larger datasets, the benefit of lower bias diminishes, and the computational cost and potential instability of LOOCV make k-fold CV a more pragmatic choice [35] [12].

Essential Research Toolkit for Cross-Validation

Implementing cross-validation in genomic research requires a suite of statistical models, software, and data components.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Cross-Validation

| Tool Category | Examples | Function in Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Models | G-BLUP (BVM) [4], Bayesian Alphabet (BayesA, BayesB, BayesC) [4], Marker Effect Models (MEM) [38] | These are the predictive models whose performance is being evaluated. They relate genotype data to phenotypic traits. |

| Software & Libraries | R (BGLR package) [4], Python (scikit-learn) [12] [37] | Provide built-in functions for efficient model fitting and cross-validation, including LOOCV and k-fold. |

| Data Components | Genotype Matrix (X), Phenotype Vector (y), Genomic Relationship Matrix (G) [38] [4] | The fundamental inputs for any genomic model. The GRM is used in G-BLUP to model genetic covariance. |

| Performance Metrics | PRESS / MSE [38], Predictive Correlation (Accuracy) [38] [4], Sensitivity & Specificity [41] | Quantify the agreement between predicted and observed values, determining model utility. |

| Morphine hydrobromide | Morphine Hydrobromide | High-purity Morphine Hydrobromide for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 2,6-Di-o-methyl-d-glucose | 2,6-Di-o-methyl-d-glucose, CAS:16274-29-6, MF:C8H16O6, MW:208.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

When to Use LOOCV: Key Use Cases and Recommendations

The decision to use LOOCV depends on dataset size, computational resources, and the need for low bias. The following diagram provides a logical flowchart to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate cross-validation method.

Figure 2: Cross-Validation Method Selection Guide. A decision flowchart for choosing between LOOCV and k-fold cross-validation based on dataset characteristics and research goals.

Based on this logic, the primary use cases for LOOCV are:

- Small Datasets: With limited data (e.g.,

nin the hundreds), LOOCV is optimal because it maximizes the information used for training in each fold, providing the most reliable error estimate [35] [42]. This is common in preliminary genomic studies or for traits with expensive phenotyping. - Model Assessment Requiring Low Bias: When an unbiased estimate is critical, and variance is a secondary concern, LOOCV is the preferred method [35].

- Specific Genomic Prediction Applications: As demonstrated in GBLUP, when efficient algorithms are available that make LOOCV computationally feasible even for thousands of observations, it becomes a viable and attractive option [38] [39].

For most other situations, particularly with large datasets (n > 10,000) or when computational efficiency is paramount, k=10-fold cross-validation is recommended as a robust default, offering a good balance between bias and variance [35] [12] [41].

Repeated and Stratified k-Fold for Enhanced Reliability

In genomic prediction (GP), the primary goal is to build statistical models that use dense molecular marker information to predict the breeding values of individuals for complex traits. The accuracy of these models directly influences the rate of genetic gain in plant and animal breeding programs, making reliable model validation indispensable [43]. Cross-validation (CV) has emerged as the cornerstone methodology for assessing how well a trained GP model will perform on unseen genotypes, providing critical insights before committing resources to costly field trials [13] [3]. The fundamental principle of CV involves partitioning a sample of data into complementary subsets, performing the analysis on one subset (the training set), and validating the analysis on the other subset (the validation or testing set) [3]. In genomic selection (GS), this process helps estimate the model's predictability, which reflects its potential applicability in a real breeding population [44].

However, standard CV techniques can produce misleading results when faced with the unique challenges of genomic data, such as population structure, class imbalance in categorical traits, and the high-dimensional nature of genotypic information (where the number of markers p far exceeds the number of individuals n) [45] [44]. These challenges can lead to problems like overfitting, where a model performs well on the data it was trained on but fails to generalize to new, independent data [44]. To address these issues, advanced CV strategies like Stratified k-Fold (SKF) and Repeated Stratified k-Fold (RSKF) have been developed. These methods are particularly vital for enhancing the reliability and robustness of performance estimates in genomic prediction, ensuring that selection decisions are based on accurate and realistic model assessments [45] [46].

Understanding the Core Methods

Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation (SKF)

Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation is an enhancement of the standard k-fold approach specifically designed for classification tasks or scenarios with imbalanced data. It ensures that each fold of the CV process preserves the same proportion of class labels as the full dataset [46] [12]. In the context of genomic prediction, this is crucial for phenotypes such as disease resistance (e.g., resistant vs. susceptible) where one class might be severely underrepresented. Preserving the class distribution in each fold prevents a situation where a fold contains no members of the minority class, which would make it impossible to evaluate the model's performance for that class [45].

The algorithm for SKF, as outlined in scientific literature, operates as follows. First, for each class in the dataset, it calculates the number of samples to be allocated to each of the k folds. It then randomly selects the appropriate number of samples from that class and assigns them to each fold. This process is repeated for every class, ensuring that every fold maintains the original dataset's class distribution [45]. This stratification is vital for obtaining a realistic estimate of model performance on imbalanced genomic datasets, a common occurrence in plant and animal breeding.

Repeated Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation (RSKF)

Repeated Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation builds upon the foundation of SKF by repeating the entire stratification and splitting process multiple times. In each repetition, the data is randomly shuffled and then split into k stratified folds, but with a different random initialization [46]. For example, with 5 repeats (n_repeats=5) of 10-fold CV, 50 different models would be fitted and evaluated. The final performance estimate is the mean of the results across all folds from all runs [46].

The key benefit of this repetition is the significant reduction in the variance of the performance estimate. A single run of k-fold CV can yield a noisy estimate because the model's performance might be particularly good or bad due to a specific, fortunate, or unfortunate random split of the data [46]. By repeating the process with different random splits, RSKF averages out this randomness, leading to a more stable and reliable measure of a model's predictive ability. While this comes at the cost of increased computational expense, the resulting gain in estimate reliability is often essential for making robust comparisons between different genomic prediction models [13] [46].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

To objectively compare the performance and utility of Stratified and Repeated Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation, their characteristics and reported outcomes are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stratified vs. Repeated Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation