From Association to Action: A Comprehensive Guide to Candidate Gene Discovery in GWAS

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the critical transition from genome-wide association study (GWAS) signals to biologically validated candidate genes.

From Association to Action: A Comprehensive Guide to Candidate Gene Discovery in GWAS

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the critical transition from genome-wide association study (GWAS) signals to biologically validated candidate genes. It covers foundational principles, state-of-the-art computational and functional methodologies, strategies for overcoming common challenges like linkage disequilibrium and false positives, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging techniques, this guide aims to enhance the efficiency and success rate of translating statistical genetic associations into meaningful biological insights and therapeutic targets.

Beyond the Hype: Decoding GWAS Signals and the Fundamental Challenge of Gene Assignment

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revolutionized human genetics, successfully identifying thousands of statistical associations between genetic variants and complex traits and diseases [1] [2]. This "GWAS promise" has provided invaluable biological insights and guided drug target discovery. However, a significant bottleneck remains: the "Gene Assignment Problem." The vast majority of GWAS variants are located in non-coding regions of the genome and are in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with many other variants, making it difficult to pinpoint the causal variant and, more importantly, the causal gene it affects [1] [3]. This challenge is a central focus in modern candidate gene discovery. Moving from a statistical locus to a biologically and therapeutically relevant causal gene requires a sophisticated integration of computational methods and functional evidence. This guide details the methodologies and resources enabling this critical transition.

The Scale and Nature of the Gene Assignment Problem

The challenge of gene assignment is intrinsic to the structure of the human genome and study design.

- Non-Coding Variants and Linkage Disequilibrium: Typically, a GWAS identifies a lead single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that serves as a statistical marker for a genomic locus. This locus, due to LD, can contain numerous correlated SNPs. Furthermore, most of these SNPs are non-coding, meaning they likely influence gene regulation rather than protein function directly, and their target genes may be hundreds of kilobases away [3] [4]. This makes simple proximity-based gene assignment error-prone.

- The Problem of Fine-Mapping: Fine-mapping is the process of distinguishing the true causal variant(s) from other non-causal but correlated variants in a locus. This is a major challenge because nearby variants on the same chromosome are often inherited together without recombination [1]. A study that provided systematic fine-mapping across 133,441 published GWAS loci identified only 729 loci that could be fine-mapped to a single coding causal variant and colocalized with a single gene, highlighting the difficulty of this task [5].

Methodologies for Prioritizing Causal Genes

Researchers use a multi-faceted approach, integrating genetic and functional genomic data to prioritize genes within a GWAS locus.

Computational Prioritization Tools and Frameworks

Several sophisticated tools have been developed to systematically evaluate and rank candidate genes. These tools are typically trained on "gold-standard" sets of known causal genes and use machine learning to identify features predictive of causality.

Table 1: Key Features for Computational Gene Prioritization

| Feature Category | Specific Data Type | Description and Role in Prioritization |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Evidence | Fine-mapping Probability (PIP) | The posterior probability that a variant is causal from statistical fine-mapping; a higher PIP increases confidence [3] [5]. |

| Distance to GWAS Lead Variant | A simple but adjusted-for-bias feature; closer genes are somewhat more likely, but tools correct for this inherent bias [3]. | |

| Functional Genomic Evidence | Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL/pQTL) | Colocalization analysis tests if the GWAS signal and a gene expression (eQTL) or protein abundance (pQTL) signal share the same causal variant, directly linking a variant to a target gene [5]. |

| Chromatin Interaction (Hi-C, PCHi-C) | Data from assays capturing 3D chromatin structure can physically connect a distal variant to the promoter of a gene it regulates [3] [5]. | |

| Epigenomic Marks (ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq) | Evidence of open chromatin (ATAC-seq) or specific histone marks (H3K27ac) in relevant cell types can indicate a variant lies in a functional regulatory element [5]. | |

| Gene-Based Features | Constraint (pLI, hs) | Metrics like probability of being loss-of-function intolerant (pLI) indicate that a gene is sensitive to mutational burden and may be critical for biological processes [3]. |

| Network Connectivity | Methods like GRIN leverage the principle that true positive genes for a complex trait are more likely to be functionally interconnected in biological networks than random genes [4]. |

Leading Tools:

- CALDERA: A state-of-the-art tool that uses a simpler logistic regression model with LASSO, trained on a data-driven truth set while correcting for potential confounders like proximity bias. It has been shown to outperform other methods like FLAMES and L2G in benchmarks [3].

- Open Targets Genetics: A comprehensive, open resource that integrates GWAS summary statistics (from the GWAS Catalog and UK Biobank) with transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data. It employs a machine-learning model to systematically prioritize causal genes and variants across thousands of traits [5].

- GRIN (Gene set Refinement through Interacting Networks): This approach does not prioritize single genes initially. Instead, it starts with a broader set of candidate genes (e.g., from a relaxed GWAS threshold) and refines the set by retaining only those genes that are strongly interconnected within a large, multiplex biological network. This effectively filters out false positives that are not functionally related to the core gene set [4].

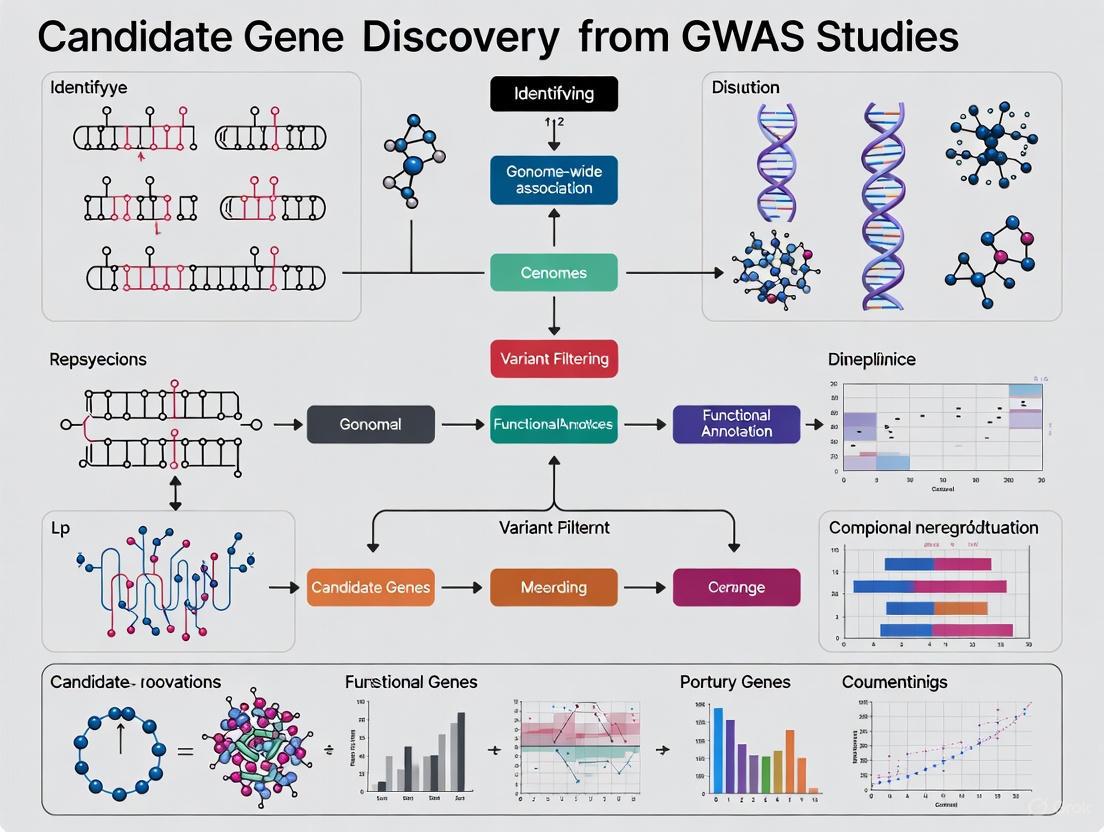

Diagram 1: The GRIN workflow for refining candidate gene sets based on biological network interconnectedness [4].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Computational prioritization generates hypotheses that must be tested experimentally. Below are detailed protocols for key functional validation experiments.

Protocol 1: Massively Parallel Reporter Assay (MPRA) Objective: To empirically test thousands of genetic variants for their regulatory potential (e.g., enhancer activity) in a high-throughput manner.

- Oligo Library Design: Synthesize a library of oligonucleotides (~200 bp) centered on each candidate SNP, including both the reference and alternative alleles.

- Library Cloning: Clone the oligo library into a reporter plasmid upstream of a minimal promoter and a barcoded reporter gene (e.g., GFP, luciferase).

- Cell Transfection: Transfect the pooled plasmid library into relevant cell lines (e.g., neuronal cells for psychiatric traits) using an appropriate method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation). Include a sample for input DNA quantification.

- RNA Extraction & Sequencing: After 48 hours, extract total RNA and convert to cDNA. Use high-throughput sequencing to quantify the abundance of each barcode from the input DNA (representing potential) and the cDNA (representing expressed RNA).

- Data Analysis: For each variant, calculate the ratio of RNA barcodes to DNA barcodes. A significant difference in this ratio between the reference and alternative alleles indicates the variant has allele-specific regulatory activity.

Protocol 2: CRISPR-based Functional Validation in Cell Models Objective: To determine the phenotypic consequence of perturbing a candidate gene or regulatory element in a biologically relevant context.

- gRNA Design and Delivery: Design and synthesize guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the candidate causal SNP or the promoter of the candidate gene. A non-targeting gRNA serves as a control. Package gRNAs with a Cas9 nuclease (for knockout) or dCas9-KRAB (for repression) into a lentiviral vector.

- Cell Line Selection and Infection: Select a cell line that is relevant to the disease (e.g., iPSC-derived neurons, hepatocytes). Infect the cells with the lentivirus at a low MOI to ensure single-copy integration. Select transduced cells using a antibiotic resistance marker (e.g., puromycin).

- Phenotypic Assay: Perform a tailored assay 5-7 days post-infection.

- For Gene Knockout: Measure changes in relevant pathways via RNA-seq (transcriptome) or Western blot (protein).

- For Regulatory Element Perturbation: Measure the expression of the putative target gene via qPCR or a targeted RNA-seq assay.

- Analysis: Compare the phenotype of cells with the targeted perturbation to the non-targeting control. A significant change in the expected direction provides strong evidence for the gene's or element's role in the disease-associated pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Candidate Gene Discovery

| Reagent / Resource | Category | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank Summary Statistics | Data Resource | Provides large-scale GWAS summary statistics for a vast array of phenotypes, serving as a primary source for discovery and fine-mapping [5]. |

| GWAS Catalog | Data Resource | A curated, public repository of all published GWAS, allowing researchers to query known trait-variant associations and access summary statistics [6]. |

| GTEx / eQTL Catalog | Data Resource | Databases of genetic variants associated with gene expression across human tissues; crucial for colocalization analyses [5]. |

| SuSiE | Software | A statistical tool for fine-mapping credible sets of causal variants from GWAS summary statistics [3]. |

| Open Targets Platform | Web Portal | An integrative platform for target identification and prioritization, linking genetic associations with functional genomics and drug information [5]. |

| CALDERA / GRIN | Software | Gene prioritization tools that use machine learning and network biology, respectively, to identify the most likely causal genes from GWAS loci [3] [4]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Experimental Reagent | Enables precise genome editing for functional validation of candidate genes and regulatory elements in cellular models. |

| iPSC Differentiation Kits | Experimental Reagent | Allows for the generation of disease-relevant cell types (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes) from induced pluripotent stem cells for functional studies. |

| Tri-GalNAc(OAc)3 TFA | Tri-GalNAc(OAc)3 TFA, MF:C81H129F3N10O38, MW:1907.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anemarsaponin E | Anemarsaponin E, MF:C46H78O19, MW:935.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: A holistic workflow from GWAS locus to validated causal gene.

The journey from a GWAS statistical signal to a confirmed causal gene is complex but increasingly tractable. The gene assignment problem is being systematically addressed by a powerful synergy of advanced statistical genetics, integrative bioinformatics, and high-throughput functional genomics. By leveraging open resources like the Open Targets Platform, employing robust computational tools like CALDERA and GRIN, and following up with rigorous experimental validation, researchers can confidently identify causal genes. This progress is transforming the initial "GWAS promise" into a tangible pipeline for elucidating disease biology and discovering novel, genetically validated therapeutic targets.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the genetic architecture of complex traits and diseases. A pivotal discovery emerging from nearly two decades of GWAS research is that over 90% of disease- and trait-associated variants map to non-coding regions of the genome [7]. This observation challenges the long-standing candidate gene approach, which predominantly focused on protein-coding mutations and often assumed linear proximity implied functional relevance. This technical review examines the molecular mechanisms whereby non-coding variants exert regulatory effects over vast genomic distances, explores advanced methodologies for variant interpretation, and discusses the implications for therapeutic development. By synthesizing recent advances in functional genomics, we provide a framework for moving beyond the nearest gene paradigm toward a more accurate, systems-level understanding of gene regulation in health and disease.

The GWAS Revolution and the Demise of the Candidate Gene Approach

The Statistical Power of GWAS Over Candidate Gene Studies

The candidate gene approach, which dominated genetic research prior to the GWAS era, was built on pre-selecting genes based on presumed biological relevance to a phenotype. This method suffered from high rates of false positives and irreproducibility due to limited statistical power and incomplete understanding of disease biology [2]. In contrast, GWAS employs a hypothesis-free framework that systematically tests hundreds of thousands to millions of genetic variants across the genome for association with traits or diseases. This agnostic approach has revealed that the genetic architecture of most complex traits is:

- Highly polygenic: Influenced by thousands of variants with small effect sizes rather than a few major genes [2]

- Enriched in non-coding regions: >90% of disease-associated variants lie outside protein-coding exons [7]

- Diffusely distributed: Risk variants are spread across the genome rather than clustered in biologically obvious candidate genes [2]

The Problem with "Nearest Gene" Annotations

The persistent practice of annotating GWAS hits by their nearest gene reflects computational convenience rather than biological accuracy. Several key findings demonstrate why this approach is fundamentally flawed:

- Long-range regulation: Enhancers can physically interact with promoters located megabases away, sometimes skipping multiple intervening genes [7]

- Complex architecture: A single non-coding variant may regulate multiple genes, while a single gene may be influenced by numerous distal regulatory elements [8]

- Tissue-specific effects: Regulatory relationships are highly context-dependent, with the same variant potentially affecting different genes in different cell types [9]

Table 1: Key Limitations of the Nearest Gene Approach

| Limitation | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Proximity Assumption | Assumes regulatory elements primarily influence closest gene | Misses long-range regulatory interactions |

| Context Ignorance | Fails to account for tissue- and cell-type-specific regulation | Incorrect gene assignment across biological contexts |

| Oversimplification | Collapses complex many-to-many relationships into one-to-one mappings | Loss of polygenic and pleiotropic effects |

| Static Annotation | Uses fixed genomic coordinates without considering 3D architecture | Inaccurate functional predictions |

Molecular Mechanisms of Long-Range Gene Regulation

Cis-Regulatory Elements and Their Disruption by Non-Coding Variants

Non-coding DNA contains multiple classes of cis-regulatory elements (CREs) that precisely control spatial, temporal, and quantitative gene expression patterns. These include:

- Enhancers: Distal regulatory elements that enhance transcription of target genes through physical looping interactions [7]

- Promoters: Regions surrounding transcription start sites that recruit basal transcriptional machinery [7]

- Insulators: Elements that block inappropriate enhancer-promoter interactions [8]

- Silencers: Sequences that repress gene expression in specific contexts [7]

Non-coding variants can disrupt these elements by altering transcription factor (TF) binding sites, either creating novel sites (gain-of-function) or eliminating existing ones (loss-of-function) [7]. Even single-nucleotide changes can significantly impact TF binding affinity, with downstream consequences for gene expression networks.

Chromatin Architecture and 3D Genome Organization

Higher-order chromatin structure enables regulatory elements to act over large genomic distances. Key mechanisms include:

- DNA looping: Mediated by protein complexes including CTCF and cohesin, bringing distal elements into physical proximity with promoters [8]

- Topologically associating domains (TADs): Self-interacting genomic regions that constrain enhancer-promoter interactions [8]

- Nuclear organization: Subnuclear localization to transcriptionally active or repressed compartments [8]

Non-coding variants can alter these architectural features, leading to dysregulated gene expression. For example, structural variants that disrupt TAD boundaries can cause pathogenic enhancer hijacking, where enhancers inappropriately activate oncogenes [8].

Diagram: Molecular mechanisms linking non-coding variants to disease phenotypes. Non-coding variants disrupt gene regulation through multiple interconnected pathways including transcription factor binding, chromatin organization, and RNA processing.

The Expanding Role of Non-Coding RNAs

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) represent another crucial mechanism of gene regulation that can be disrupted by non-coding variants. These RNA molecules, defined as >200 nucleotides with no protein-coding potential, function through diverse mechanisms:

- Chromatin modification: Recruiting or blocking histone-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci [8]

- Transcriptional interference: Physically impeding transcription machinery assembly [8]

- Nuclear organization: Serving as scaffolds for nuclear bodies or facilitating chromosomal looping [8]

- Post-transcriptional regulation: Sequestering miRNAs or modulating RNA stability [8]

Variants in lncRNA genes or their regulatory elements can disrupt these functions, with disease consequences. For example, the lncRNA CCAT1-L regulates long-range chromatin interactions at the MYC locus, and its dysregulation is associated with colorectal cancer [8].

Advanced Methodologies for Mapping Variant-to-Gene Relationships

Experimental Approaches for Functional Validation

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Validating Non-Coding Variant Function

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| TF Binding assays | EMSA [7], HiP-FA [7], BET-seq [7], STAMMP [7] | Quantifying TF-DNA binding affinity | High-resolution energy measurements; some enable massively parallel testing |

| Reporter Assays | MPRAs [7], NaP-TRAP [10] | Functional screening of variant effects | High-throughput assessment of transcriptional/translational consequences |

| Chromatin Conformation | Hi-C, ChIA-PET, HiChIRP [8] | Mapping 3D genome architecture | Identifies physical enhancer-promoter interactions |

| CRISPR screens | CRISPRi, CRISPRa, base editing | Functional validation of regulatory elements | Enables targeted perturbation of specific variants |

Detailed Protocol: Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs)

MPRAs enable high-throughput functional characterization of thousands of non-coding variants in a single experiment:

- Library Design: Synthesize oligonucleotides containing reference and alternative alleles of target variants within their native genomic context (typically 150-500bp fragments)

- Vector Construction: Clone oligonucleotide library into reporter vectors upstream of a minimal promoter and barcoded reporter gene (e.g., GFP, luciferase)

- Cell Transduction: Deliver library to relevant cell types via viral transduction or transfection

- Expression Quantification: After 24-72 hours, extract RNA and quantify barcode abundance via sequencing to measure transcriptional output

- Data Analysis: Compare barcode counts between alternative alleles to calculate effect sizes on regulatory activity

Recent advancements like NaP-TRAP (Nascent Peptide-Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification) extend this approach to specifically measure translational consequences of 5'UTR variants, capturing post-transcriptional regulatory effects [10].

Detailed Protocol: HiChIRP for RNA-Chromatin Interactions

HiChIRP (Hi-C with RNA Pull-down) maps genome-wide interactions between specific lncRNAs and chromatin:

- Cell Fixation: Crosslink cells with formaldehyde to preserve RNA-chromatin interactions

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Digest chromatin with restriction enzyme or via sonication

- Probe Hybridization: Incubate with biotinylated antisense oligonucleotides targeting specific lncRNAs

- Affinity Purification: Capture RNA-DNA complexes using streptavidin beads

- Library Preparation: Process purified complexes for Hi-C sequencing to identify chromatin interactions

- Data Analysis: Map sequencing reads to generate contact matrices and identify statistically significant interactions

This approach revealed that the lncRNA Firre anchors the inactive X chromosome to the nucleolus by binding CTCF, maintaining H3K27me3 methylation [8].

Computational Prediction Frameworks

Computational methods have evolved from simple motif-based analyses to sophisticated deep learning models that predict variant effects from sequence alone:

- Traditional approaches: Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) and tools like SNP2TFBS and atSNP predict TF binding disruption but assume nucleotide independence [7] [11]

- kmer-based models: gkm-SVM and Delta-SVM use k-mer frequencies to predict regulatory potential without predefined motifs [11]

- Deep learning models: DeepSEA, Basset, and DanQ employ convolutional neural networks to predict functional genomic profiles from DNA sequence [11]

- Foundation models: Emerging approaches like EMO use transformer architectures pretrained on large genomic datasets then fine-tuned for specific prediction tasks [9] [11]

These computational tools are essential for prioritizing non-coding variants for functional validation, with the most advanced models integrating DNA sequence with epigenomic data across tissues and single-cell contexts [9].

Diagram: Computational workflow for predicting non-coding variant effects. Modern approaches have evolved from simple motif scanning to deep learning models that integrate multiple genomic signals for accurate variant interpretation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Non-Coding Variant Functionalization

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | dbSNP [7], gnomAD [12] [10], ClinVar [12] | Cataloging human genetic variation | Population allele frequencies, clinical annotations |

| Functional Genomics | ENCODE [11], Roadmap Epigenomics [11], GTEx [9] | Reference regulatory element annotations | Multi-assay epigenomic profiles across tissues/cell types |

| Variant Prediction | ESM1b [13], DeepSEA [11], FunsEQ2 [11] | Computational effect prediction | Deep learning models for pathogenicity scoring |

| Experimental Reagents | Oligo libraries [7], CRISPR guides [10], Antibodies (CTCF, histone modifications) [8] | Functional validation | Enable targeted perturbation and measurement |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The accurate assignment of non-coding variants to their target genes has profound implications for therapeutic development:

- Target identification: Misassignment of variants to incorrect genes leads to wasted resources pursuing biologically irrelevant targets [2]

- Patient stratification: Proper understanding of regulatory mechanisms enables more precise genetic stratification for clinical trials [10]

- Modality selection: Variants affecting different regulatory mechanisms (e.g., TF binding vs. chromatin structure) may require different therapeutic approaches [8]

- Safety assessment: Understanding pleiotropic effects of non-coding variants helps predict potential on-target toxicities [2]

Emerging evidence suggests that non-coding variants with strong effects on translation in oncogenes and tumor suppressors are enriched in cancer databases like COSMIC, highlighting their clinical relevance as potential therapeutic targets [10].

The nearest gene approach represents an outdated heuristic that fails to capture the complex regulatory architecture of the human genome. GWAS has revealed a landscape dominated by non-coding variants that regulate gene expression through sophisticated mechanisms acting over large genomic distances. Moving forward, the field requires integrated approaches that combine computational predictions based on deep learning with experimental validation using high-throughput functional assays. By embracing this multi-modal framework, researchers can accurately connect non-coding variants to their target genes, unlocking the full potential of GWAS for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutics. The era of candidate gene studies is over; we must now embrace the complexity of regulatory genomics to fully decipher the genetic basis of human disease.

This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding the interconnected roles of linkage disequilibrium (LD), population diversity, and statistical power in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Focusing on candidate gene discovery, we detail methodological considerations for designing robust genetic association studies, including quantitative approaches for calculating sample size requirements, protocols for assessing population structure, and strategies for leveraging LD patterns to enhance discovery potential. The integration of these core concepts enables more effective navigation of the analytical challenges inherent in GWAS and promotes the identification of biologically relevant candidate genes for therapeutic development.

Linkage Disequilibrium in Evolutionary and Genetic Context

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) is formally defined as the non-random association of alleles at different loci within a population [14]. This phenomenon represents a significant departure from the expectation of independent assortment and serves as a critical foundation for mapping disease genes. The fundamental measure of LD is quantified by the coefficient D, calculated as DAB = pAB - pApB, where pAB is the observed haplotype frequency of alleles A and B, and pApB is the product of their individual allele frequencies [14] [15]. When D = 0, loci are in linkage equilibrium, indicating no statistical association between them. Importantly, LD decays predictably over generations at a rate determined by the recombination frequency (c) between loci: D(t+1) = (1-c)D(t) [14]. This predictable decay pattern enables researchers to make inferences about the temporal proximity of selective events or population bottlenecks.

The persistence of LD across genomic regions provides a valuable mapping tool as it reflects the population's evolutionary history, including demographic events, mating systems, selection pressures, and recombination patterns [14]. In GWAS, the presence of LD allows researchers to detect associations between genotyped markers and untyped causal variants, significantly reducing the number of polymorphisms that need to be directly assayed [14] [16]. However, this same property also limits mapping resolution, as associated regions may contain multiple genes in high LD with each other, complicating the identification of truly causal variants [17].

Population Diversity and Genetic Architecture

Population diversity profoundly influences both LD structure and study power in GWAS. The genetic architecture of a population—shaped by its demographic history, migration patterns, effective population size, and natural selection—creates distinctive patterns of LD across the genome [17] [15]. Populations with recent bottlenecks or extensive admixture typically exhibit longer-range LD, while historically larger populations show more rapid LD decay [17]. These differences have practical implications for GWAS design, as the number of markers required to capture genetic variation depends on the extent of LD in the study population [16].

The historical focus on European-ancestry populations in GWAS has created significant gaps in our understanding of genetic architecture across diverse human populations [18] [19]. This lack of diversity not only limits the generalizability of findings but also reduces the power to detect associations in underrepresented groups. Furthermore, populations with different LD patterns can provide complementary information for fine-mapping causal variants, as regions with shorter LD blocks enable higher-resolution mapping [19]. Initiatives such as All of Us, Biobank Japan, and H3Africa are addressing these disparities by collecting genomic data from diverse populations, creating new opportunities for more inclusive and powerful genetic studies [18].

Statistical Power in Genetic Association Studies

Statistical power in GWAS represents the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis when a true genetic effect exists [20]. In practical terms, it reflects the likelihood that a study will detect genuine genetic associations at a specified significance level. Power depends on multiple factors including sample size, effect size of the variant, allele frequency, disease prevalence (for binary traits), and the stringency of multiple testing correction [20] [21] [16]. The complex interplay of these factors necessitates careful power calculations prior to study initiation to ensure adequate sample collection and appropriate design implementation.

Underpowered studies represent a critical concern in GWAS, as they frequently fail to detect true associations and generate irreproducible results [20] [16]. Conversely, overpowered studies may waste resources without meaningful scientific gain [20]. The polygenic architecture of most complex traits further complicates power calculations, as the distribution of effect sizes across the genome must be considered rather than focusing on single variants in isolation [21]. Advanced power calculation methods now account for this complexity by modeling the entire distribution of genetic effects, enabling more accurate predictions of GWAS outcomes [21].

Table 1: Key Parameters Affecting GWAS Power

| Parameter | Impact on Power | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Increases with larger samples | Diminishing returns; cost considerations |

| Effect Size | Increases with larger effects | OR > 2.0 provides reasonable power with moderate samples |

| Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) | Highest for intermediate frequencies (MAF ~0.5) | Very rare variants (MAF <0.01) require extremely large samples |

| Significance Threshold | Decreases with more stringent thresholds | Genome-wide significance typically p < 5×10-8 |

| LD with Causal Variant | Increases with stronger LD (r2) | Power ≈ N×r2 for indirect association |

| Trait Heritability | Increases with higher heritability | Affected by measurement precision |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

LD Assessment and Visualization Protocols

Comprehensive assessment of LD patterns represents a critical first step in GWAS design and interpretation. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for LD analysis:

Step 1: Data Quality Control Begin with genotype data in PLINK format (.bed, .bim, .fam). Apply quality control filters to remove markers with high missingness (>5%), significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 1×10-6), and minor allele frequency below the chosen threshold (typically MAF <0.01 for population-specific analyses) [18]. Sample-level filtering should exclude individuals with excessive missingness (>10%) and unexpected relatedness (pi-hat >0.2) [17].

Step 2: Population Stratification Assessment Perform multidimensional scaling (MDS) or principal component analysis (PCA) to identify potential population substructure [17] [22]. Visualize the first several principal components to detect clustering patterns that may correspond to ancestral groups. For structured populations, include principal components as covariates in association tests to minimize spurious associations [22].

Step 3: LD Calculation

Using quality-controlled genotypes, calculate pairwise LD between SNPs using the r² metric implemented in PLINK (--r2 command) or specialized tools like Haploview [17]. The r² parameter represents the squared correlation coefficient between alleles at two loci and directly measures the statistical power of indirect association [15] [16]. For a genomic region of interest, compute LD in sliding windows (typically 1 Mb windows with 100 kb steps) to balance computational efficiency with comprehensive coverage.

Step 4: LD Decay Analysis Calculate physical or genetic distances between SNP pairs and model the relationship between distance and LD. Plot r² values against inter-marker distance and fit a nonlinear decay curve (often a loess smooth or exponential decay function) [17]. Determine the LD decay distance by identifying the point at which r² drops below a predetermined threshold (commonly 0.2 or the half-decay point) [17]. This distance estimate informs the density of markers needed for comprehensive genomic coverage.

Step 5: Haplotype Block Definition Apply block-partitioning algorithms (such as the confidence interval method) to identify genomic regions with strong LD and limited historical recombination [14]. These haplotype blocks represent chromosomal segments that are inherited as units and may contain multiple correlated variants. Define block boundaries where pairwise LD drops below a specific threshold (commonly D' <0.7) [14].

Step 6: Visualization Generate LD heatmaps using tools like Haploview or dedicated R packages (e.g., ggplot2, LDheatmap) [14]. These visual representations use color-coded matrices to display pairwise LD statistics, enabling rapid identification of haplotype blocks and recombination hotspots. Complement with LD decay plots that show the relationship between genetic distance and LD strength [17].

Diagram 1: LD Assessment Workflow

Power Calculation Methods for Study Design

Robust power calculation ensures that GWAS are adequately sized to detect genetic effects of interest while using resources efficiently. The following methods provide comprehensive power assessment:

Analytical Power Calculation For simple genetic association studies, closed-form analytical solutions exist to compute power. The non-centrality parameter (NCP) for a quantitative trait can be derived as NCP = N × β², where N is sample size and β is the effect size [20]. The statistical power is then calculated from the non-central chi-squared distribution with this NCP. For case-control designs with binary outcomes, power calculations incorporate disease prevalence, case-control ratio, and the genetic model (additive, dominant, recessive) [21]. Tools like the Genetic Power Calculator (GPC) implement these analytical approaches for standard study designs [21] [16].

Polygenic Power Calculation For complex traits with polygenic architecture, methods that account for the joint distribution of effect sizes across the genome provide more accurate power estimates [21]. Under the point-normal model, effect sizes follow a mixture distribution:

β ∼ π₀δ₀ + (1-π₀)N(0, h²/m(1-π₀))

where π₀ is the proportion of null SNPs, δ₀ is a point mass at zero, h² is SNP heritability, and m is the number of independent SNPs [21]. This model enables calculation of the expected number of genome-wide significant hits, the proportion of heritability explained by these hits, and the predictive accuracy of polygenic scores [21].

Simulation-Based Approaches When analytical solutions are infeasible due to study complexity, simulation methods provide a flexible alternative [20] [23]. These approaches involve: (1) generating genotype data based on existing reference panels or population genetic models; (2) simulating phenotypes conditional on genotypes according to specified genetic models; (3) performing association tests on the simulated data; and (4) repeating the process multiple times to estimate empirical power as the proportion of simulations where significant associations are detected [23]. Tools like PowerBacGWAS implement such approaches for specialized applications [23].

Sample Size Calculation Protocol

- Define Target Parameters: Specify the minimum detectable effect size (odds ratio or variance explained), minor allele frequency, significance threshold (typically p < 5×10â»â¸ for genome-wide significance), and desired power (conventionally 80%) [20] [21].

- Select Calculation Method: Choose analytical, polygenic, or simulation-based approaches based on study complexity and trait architecture.

- Incorporate LD Structure: For indirect association studies, adjust for LD between tag SNPs and causal variants using the r² metric, as power is approximately proportional to N × r² [16].

- Account for Multiple Testing: Apply Bonferroni correction based on the effective number of independent tests or use more sophisticated approaches that consider the correlation structure among tests [16].

- Consider Practical Constraints: Balance statistical requirements with available resources, including genotyping costs, sample availability, and recruitment timelines.

Table 2: Sample Size Requirements for GWAS (80% Power, α = 5×10â»â¸)

| Minor Allele Frequency | Odds Ratio = 1.2 | Odds Ratio = 1.5 | Odds Ratio = 2.0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | >100,000 | ~25,000 | ~10,000 |

| 0.05 | ~50,000 | ~12,000 | ~5,000 |

| 0.20 | ~20,000 | ~6,000 | ~2,500 |

| 0.50 | ~15,000 | ~4,500 | ~2,000 |

Population Diversity Assessment Protocol

Comprehensive characterization of population diversity ensures proper interpretation of GWAS results and enables cross-population validation. The following protocol standardizes diversity assessment:

Step 1: Genotype Data Collection and QC Obtain high-quality genotype data for all study participants, applying standard QC filters as described in Section 2.1. For diverse populations, ensure balanced representation of all ancestral groups and careful handling of admixed individuals [19].

Step 2: Ancestry Inference Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., ADMIXTURE) to genome-wide data to estimate individual ancestry proportions [19]. Use reference panels from the 1000 Genomes Project or the Human Genome Diversity Project to provide ancestral context. Visualize results using bar plots showing individual ancestry proportions.

Step 3: Population Structure Quantification Perform principal component analysis on the combined study sample and reference populations [17] [22]. Retain significant principal components that capture population structure for use as covariates in association analyses. Compute FST statistics to quantify genetic differentiation between subpopulations [19].

Step 4: LD Pattern Comparison Calculate and compare LD decay patterns across different ancestral groups within the study [17]. Document differences in extent and block structure of LD, as these affect fine-mapping resolution and tag SNP selection [16] [19].

Step 5: Genetic Diversity Metrics Compute standard diversity measures including observed and expected heterozygosity, nucleotide diversity (Ï€), and Tajima's D for each population subgroup [17]. These metrics provide insight into the demographic history and selective pressures that have shaped each population's genetic architecture.

Step 6: Association Testing in Context For each identified genetic association, test for heterogeneity of effect sizes across populations [19]. Evaluate whether associations replicate across diverse groups, which provides stronger evidence for true biological effects and reduces the likelihood of population-specific confounding.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Software | PLINK [18], SNPTEST [18] | Genome-wide association analysis | Core association testing, quality control, basic population stratification control |

| Power Calculation | Genetic Power Calculator [21] [16], Polygenic Power Calculator [21], PowerBacGWAS [23] | Sample size and power estimation | Study design, sample size determination, resource allocation |

| LD Analysis | Haploview, PLINK LD functions [18] | Linkage disequilibrium calculation and visualization | LD assessment, haplotype block definition, tag SNP selection |

| Population Structure | ADMIXTURE, FastStructure [17], EIGENSTRAT [22] | Population stratification inference | Ancestry estimation, structure correction, diversity assessment |

| Genetic Databases | HapMap [14] [18], 1000 Genomes [22], UK Biobank [18], gnomAD | Reference genotype data | LD reference, frequency data, imputation panels |

| Fine-Mapping | CAVIAR [18], PAINTOR [18] | Causal variant identification | Prioritizing likely causal variants from association signals |

| Imputation Tools | Beagle [18], IMPUTE2, Minimac3 | Genotype imputation | Increasing marker density, meta-analysis, cross-platform integration |

| Visualization | QQman [18], LocusZoom, ggplot2 | Result visualization | Manhattan plots, QQ plots, regional association plots |

Integration for Candidate Gene Discovery

The successful identification of candidate genes from GWAS requires thoughtful integration of LD patterns, population diversity considerations, and statistical power optimization. The following integrative approach enhances discovery potential:

LD-Informed Fine-Mapping Strategy

After identifying associated regions through GWAS, implement a fine-mapping protocol to narrow candidate intervals [18]. Leverage population differences in LD patterns to improve resolution; variants that show association across multiple populations with different LD structures help narrow the candidate region [19]. Incorporate functional genomic annotations (e.g., chromatin state, regulatory elements) to prioritize variants within LD blocks that overlap biologically relevant genomic features. Use statistical fine-mapping tools (e.g., CAVIAR, PAINTOR) to compute posterior probabilities of causality for each variant in the associated region [18].

Cross-Population Validation Framework

Establish a systematic approach for validating associations across diverse populations [19]. This includes testing for heterogeneity of effect sizes, which may indicate population-specific genetic effects or environmental interactions. Associations that replicate consistently across diverse populations provide stronger evidence for true biological effects and reduce the likelihood of false positives due to population stratification [19]. Furthermore, cross-population meta-analysis can boost power for detection of associations that have consistent effects across ancestries [19].

Power-Optimized Study Designs

Implement power-enhancing strategies throughout the study lifecycle. For fixed budgets, consider the trade-off between sample size and marker density; in many cases, power is improved by genotyping more individuals at moderate density rather than fewer individuals at high density [16]. Utilize genotype imputation to increase marker density cost-effectively, leveraging reference panels from diverse populations to improve imputation accuracy across ancestries [18] [22]. For rare variants, consider burden tests or aggregation methods that combine signals across multiple variants within functional units [23] [22].

Diagram 2: Candidate Gene Discovery Pipeline

Interpretation Framework for Candidate Gene Prioritization

Develop a systematic scoring system to prioritize candidate genes within associated loci. This framework should incorporate: (1) functional genomic evidence (regulation in relevant tissues, protein-altering consequences); (2) biological plausibility (pathway membership, known biology); (3) cross-species conservation; (4) replication across diverse populations; and (5) concordance with other omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) [22]. This multi-dimensional approach increases confidence in candidate gene selection for downstream functional validation and therapeutic targeting.

The integration of linkage disequilibrium understanding, population diversity considerations, and statistical power optimization forms the foundation of successful candidate gene discovery in GWAS. By implementing the methodologies and frameworks outlined in this technical guide, researchers can design more robust association studies, interpret results within appropriate genetic contexts, and prioritize candidate genes with greater confidence. As GWAS continue to expand in scale and diversity, these core concepts will remain essential for translating statistical associations into biological insights and therapeutic opportunities. The ongoing development of more sophisticated analytical methods and more diverse genomic resources promises to further enhance our ability to decipher the genetic architecture of complex traits and diseases across human populations.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and rare-variant burden tests are foundational tools for identifying genes associated with complex traits and diseases. Despite their conceptual similarities, these methods systematically prioritize different genes, leading to distinct biological interpretations and implications for downstream applications like drug target discovery [24] [25]. This divergence stems from fundamental differences in what each method measures and the biological constraints acting on different variant types. Understanding these systematic differences is crucial for accurately interpreting association study results and developing effective gene prioritization strategies.

Recent research analyzing 209 quantitative traits from the UK Biobank has demonstrated that burden tests and GWAS rank genes discordantly [25]. While a majority of burden hits fall within GWAS loci, their rankings show little correlation, with only 26% of genes with burden support located in top GWAS loci [25]. This technical guide examines the mechanistic bases for these divergent rankings, their implications for biological inference, and methodological considerations for researchers leveraging these approaches in candidate gene discovery.

Fundamental Mechanisms Driving Divergent Gene Rankings

Conceptual Frameworks of GWAS and Burden Tests

GWAS and burden tests operate on distinct principles despite their shared goal of identifying trait-associated genes. GWAS tests common variants (typically with minor allele frequency > 1%) individually across the genome, identifying associations whether variants fall in coding or regulatory regions [26] [27]. In contrast, burden tests aggregate rare variants (MAF < 1%) within a gene, creating a combined "burden genotype" that is tested for association with phenotypes [25] [26]. This fundamental methodological difference shapes what each approach can detect.

Table 1: Key Methodological Differences Between GWAS and Burden Tests

| Feature | GWAS | Rare-Variant Burden Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Frequency | Common variants (MAF > 1%) | Rare variants (MAF < 1%) |

| Unit of Analysis | Single variants | Gene-based variant aggregates |

| Variant Impact | Coding and regulatory variants | Primarily protein-altering variants |

| Statistical Power | High for common variants | Increased power for rare variants |

| Primary Signal | Trait-associated loci | Trait-associated genes |

The statistical properties of these tests further differentiate their applications. Burden tests gain power by aggregating multiple rare variants but require careful selection of which variants to include through "masks" that typically focus on likely high-impact variants like protein-truncating variants or deleterious missense variants [26]. GWAS maintains power for common variants but faces multiple testing challenges and difficulties in linking non-coding variants to causal genes [25].

Biological Constraints: Selective Pressures and Pleiotropy

Natural selection exerts distinct pressures on the variant types detected by each method, fundamentally shaping their results. Rare protein-altering variants detected by burden tests are often subject to strong purifying selection because they frequently disrupt gene function [25] [28]. This selection keeps deleterious alleles rare and influences which genes show association signals.

Pleiotropy - where genes affect multiple traits - differently impacts each method. Genes affecting many traits (high pleiotropy) are often constrained by selection, reducing the frequency of severe protein-disrupting variants [25] [27]. Burden tests thus struggle to detect highly pleiotropic genes. Conversely, GWAS can identify pleiotropic genes through regulatory variants that may affect gene activity in more limited contexts or tissues, allowing these variants to escape evolutionary removal [25] [27].

Figure 1: Evolutionary constraints shape which variants are detectable by each method. High-impact variants are kept rare by selection, making them optimal for burden tests, while regulatory variants can persist at higher frequencies, enabling GWAS detection.

Theoretical Foundations: Ideal Gene Prioritization Criteria

Defining Trait Importance and Specificity

To understand why GWAS and burden tests prioritize different genes, researchers have proposed two fundamental criteria for ideal gene prioritization: trait importance and trait specificity [25].

Trait importance quantifies how much a gene affects a trait of interest, defined mathematically as the squared effect of loss-of-function (LoF) variants on that trait (denoted as γ₲ for genes) [25]. A gene with high trait importance substantially influences the trait when disrupted.

Trait specificity measures a gene's importance for the trait of interest relative to its importance across all traits, defined as ΨG := γ₲ / ∑γt² for genes [25]. A gene with high specificity primarily affects one trait with minimal effects on others.

These criteria help explain the systematic differences between methods. Burden tests preferentially identify genes with high trait specificity - those primarily affecting the studied trait with little effect on other traits [25]. GWAS can detect both high-specificity genes and genes with broader pleiotropic effects, as regulatory variants can affect genes in context-specific ways.

Method-Specific Prioritization Patterns

The preference of burden tests for trait-specific genes stems from population genetic constraints. For burden tests, the expected strength of association (z²) for a gene depends on both its trait importance (γ₲) and the aggregate frequency of LoF variants (pLoF), with E[z²] ∠γ₲ pLoF(1-pLoF) [25]. Under strong natural selection, pLoF(1-pLoF) becomes proportional to μL/shet, where μ is the mutation rate, L is gene length, and s_het is selection strength [25].

This relationship means burden tests effectively prioritize based on trait specificity rather than raw importance, as genes affecting multiple traits face stronger selective constraints (higher s_het), reducing their variant frequencies and statistical power for detection [25].

Table 2: How Gene Properties Influence Detection by Method

| Gene Property | Impact on GWAS Detection | Impact on Burden Test Detection |

|---|---|---|

| High Trait Specificity | Detectable | Strongly preferred |

| High Pleiotropy | Readily detectable | Poorly detected |

| Large Effect Size | Detectable | Detectable |

| Gene Length | Minimal influence | Strong influence (longer genes have more targets for mutation) |

| Selective Constraint | Minimal influence | Major influence (highly constrained genes have fewer rare variants) |

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Study Design and Data Processing Pipelines

Implementing robust GWAS and burden test analyses requires careful study design and data processing. The general workflow for sequencing-based association studies involves multiple critical steps [28]:

- Platform Selection: Choosing between whole-genome sequencing, exome sequencing, targeted sequencing, or genotyping arrays based on research goals and budget

- Variant Calling and Quality Control: Implementing rigorous quality control measures including contamination checks, read depth assessment, and variant quality filtering

- Functional Annotation: Using bioinformatic tools to predict variant impacts (synonymous, missense, nonsense, splicing)

- Association Testing: Applying appropriate statistical methods for variant burden testing or single-variant association

- Replication and Validation: Designing follow-up studies to confirm associations

For burden tests, defining the variant mask - which specifies which rare variants to include - is particularly critical. Masks typically focus on likely high-impact variants such as protein-truncating variants and putatively deleterious missense variants [26]. The choice of mask significantly influences power and specificity.

Figure 2: Generalized workflow for genetic association studies, highlighting parallel paths for GWAS and burden test analyses after initial data processing.

Power Considerations and Statistical Trade-offs

The relative power of burden tests versus single-variant tests depends on several genetic architecture factors:

- Proportion of causal variants: Burden tests require a high proportion of causal variants in a gene to achieve power advantage over single-variant tests [26]

- Sample size: Burden tests generally require larger sample sizes to achieve sufficient power for rare variants

- Effect direction: Burden tests perform best when rare variants in a gene have effects in the same direction, while suffering power loss with mixed effect directions [26]

- Variant frequency spectrum: Single-variant tests maintain advantage for very rare variants even in large samples [26]

For quantitative traits, the non-centrality parameter (NCP) - which determines statistical power - differs between methods. For single-variant tests, the NCP depends on sample size, variant frequency, and effect size. For burden tests, the NCP additionally depends on the proportion of causal variants and the correlation between variants' effect sizes and frequencies [26].

Technical Protocols for Association Analysis

GWAS Implementation Protocol

Implementing a robust GWAS requires the following key steps:

Genotype Data Processing: Quality control should include filtering for call rate, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, population stratification, and relatedness. Principal component analysis should be performed to account for population structure [29] [30].

Association Testing: Fit a mixed linear model for each SNP:

Where y is the phenotype, x is the genotype vector, β is the effect size, g is the polygenic effect, and ε is the residual [30].

Significance Thresholding: Apply genome-wide significance threshold (typically p < 5×10â»â¸) with multiple testing correction.

Locus Definition: Define associated loci by merging significant SNPs within specified distance (e.g., 1Mb windows) and accounting for linkage disequilibrium [25].

Variant Annotation: Annotate significant variants with functional predictions and link to nearby genes using genomic databases.

Burden Test Implementation Protocol

Implementing a robust burden test analysis involves:

Variant Filtering and Mask Definition: Select rare variants (MAF < 1%) with predicted functional impact using annotation tools. Common masks include:

- Protein-truncating variants (nonsense, frameshift, splice-site)

- Deleterious missense variants (e.g., CADD > 20, PolyPhen-2 "probably damaging")

- Custom masks based on functional predictions [26]

Variant Aggregation: Calculate burden score for each sample i in gene j:

Where K is the set of variants in the mask, wk are weights (often based on frequency or function), and Gijk is the genotype [26].

Association Testing: Regress phenotype on burden score using generalized linear models:

Accounting for relatedness and population structure [26].

Gene-Based Significance: Apply multiple testing correction across genes (e.g., Bonferroni correction for number of genes tested).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Association Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Whole-genome sequencing, Whole-exome sequencing, Targeted panels | Generate variant data across frequency spectrum |

| Genotyping Arrays | GWAS chips, Exome chips | Cost-effective variant interrogation at scale |

| Functional Annotation | CADD, PolyPhen-2, SIFT, ANNOVAR | Predict functional impact of coding and non-coding variants |

| Reference Databases | gnomAD, UK Biobank, NHLBI ESP | Provide population frequency data and comparator datasets |

| Statistical Packages | REGENIE, SAIGE, PLINK, SKAT, STAAR | Perform association testing for common and rare variants |

| Quality Control Tools | VCFtools, BCFtools, FastQC | Ensure data quality and identify technical artifacts |

| DSPE-PEG2-mal | DSPE-PEG2-mal, MF:C55H100N3O14P, MW:1058.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzyl-PEG11-Boc | Benzyl-PEG11-Boc, MF:C35H62O14, MW:706.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Biological Interpretation and Translational Applications

Complementary Biological Insights

GWAS and burden tests provide complementary views of trait biology, each highlighting distinct aspects [25]. Burden tests identify trait-specific genes with direct, often interpretable connections to disease mechanisms. These genes typically have limited pleiotropy and represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention with potentially fewer side effects [25] [27].

GWAS reveals both trait-specific genes and pleiotropic genes that influence multiple biological processes. These pleiotropic genes often play fundamental regulatory roles and may highlight core biological pathways, though their manipulation carries higher risk of unintended consequences [25].

The NPR2 and HHIP loci from height analyses exemplify this divergence. NPR2 ranks as the second most significant gene in burden tests but only the 243rd locus in GWAS, while HHIP shows the reverse pattern - third in GWAS but no burden signal [25]. Both are biologically relevant but highlight different aspects of height genetics.

Implications for Drug Discovery

The systematic differences in gene ranking have profound implications for drug target identification. Burden tests prioritize genes with high trait specificity, making them excellent candidates for drug targets with potentially favorable safety profiles [25] [27]. The identified genes often have clear mechanistic links to disease pathology.

GWAS identifies both specific targets and pleiotropic genes that may represent higher-risk therapeutic targets but could enable drug repurposing across conditions [27]. The p-values from either method alone are poor indicators of a gene's biological importance for disease processes, necessitating integrated approaches [25] [27].

Current research aims to develop methods that combine GWAS and burden test results with experimental functional data to better prioritize genes by their true biological importance rather than statistical significance alone [27]. This integration promises to streamline drug development by identifying the most promising targets while anticipating potential side effects.

GWAS and rare-variant burden tests systematically prioritize different genes due to their distinct sensitivities to trait importance versus trait specificity and the varying selective constraints acting on different variant types. Rather than viewing one method as superior, researchers should recognize their complementary nature - burden tests excel at identifying trait-specific genes with clear biological interpretations, while GWAS captures both specific and pleiotropic influences [25].

Future directions involve developing integrated approaches that leverage both methods alongside functional genomic data to better estimate true gene importance [27]. As biobanks expand and functional annotation improves, combining these approaches will enhance our ability to identify causal genes and prioritize therapeutic targets, ultimately advancing precision medicine and drug development.

The Candidate Gene Toolbox: Computational and Functional Genomics Approaches for Prioritization

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have successfully identified hundreds of thousands of genetic variants associated with complex traits and diseases. However, a persistent challenge has been moving from statistical associations to biological mechanisms, particularly when approximately 95% of disease-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) reside in non-coding regions of the genome [31]. These non-coding variants likely disrupt gene regulatory elements, but assigning them to their target genes based solely on linear proximity often leads to incorrect annotations. The discovery that eukaryotic genomes are organized into three-dimensional (3D) structures has provided a critical framework for addressing this challenge. At the heart of this organizational principle are Topologically Associating Domains (TADs)—self-interacting genomic regions where DNA sequences within a TAD physically interact with each other more frequently than with sequences outside the TAD [32]. This architectural feature has profound implications for interpreting GWAS signals and prioritizing candidate genes, leading to the development of specialized methodologies such as TAD Pathways that leverage TAD organization to illuminate the functional genomics underlying association studies [33].

Fundamental Biology of Topologically Associating Domains

Definition and Core Properties

Topologically Associating Domains are fundamental units of chromosome organization, typically spanning hundreds of kilobases in mammalian genomes. The average TAD size is approximately 880 kb in mouse cells and 1000 kb in humans, though significant variation exists across species, with fruit flies exhibiting smaller domains averaging 140 kb [32]. These domains are not arbitrary structures but represent highly conserved architectural features. TAD boundaries—the genomic regions that separate adjacent domains—show remarkable conservation between different mammalian cell types and even across species, suggesting they are under evolutionary constraint and perform essential functions [32] [34].

Table 1: Core Properties of Topologically Associating Domains Across Species

| Property | Human | Mouse | Fruit Fly (D. melanogaster) | Plants (Oryza sativa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average TAD Size | 1000 kb | 880 kb | 140 kb | Varies by genome size |

| Boundary Conservation | High between cell types | High between cell types | ~30-40% over 49 million years | Varies by evolutionary distance |

| Key Boundary Proteins | CTCF, Cohesin | CTCF, Cohesin | BEAF-32, CP190, M1BP | Cohesin (no CTCF) |

| Boundary Gene Enrichment | Housekeeping genes, tRNA genes | Housekeeping genes, tRNA genes | Active genes | Active genes, low TE content |

| Formation Mechanism | Loop extrusion | Loop extrusion | Boundary pairing, phase separation | Under investigation |

Mechanisms of TAD Formation

The prevailing model for TAD formation in mammals is the loop extrusion mechanism, where the cohesin complex binds to chromatin and progressively extrudes DNA loops until it encounters chromatin-bound CTCF proteins in a convergent orientation, typically located at TAD boundaries [32]. This process effectively defines discrete topological domains by establishing loop anchors that bring boundary regions into proximity while insulating the interior of domains from neighboring regions. The loop extrusion model is supported by in vitro observations that cohesin can processively extrude DNA loops in an ATP-dependent manner and stalls at CTCF binding sites [32]. It is important to note that TADs are dynamic, transient structures rather than static architectural features, with cohesin complexes continuously binding and unbinding from chromatin [32].

In other organisms, different mechanisms may contribute to TAD formation. In Drosophila, evidence suggests that boundary pairing and chromatin compartmentalization driven by phase separation may play important roles [35]. Plants, which lack CTCF proteins, nevertheless form TAD-like domains through mechanisms that likely involve cohesin and other as-yet unidentified factors [35]. Despite these mechanistic differences, the functional consequences appear conserved across eukaryotes—TADs establish regulatory neighborhoods that constrain enhancer-promoter interactions within defined genomic territories.

Functional Role in Gene Regulation

TADs primarily function to constrain gene regulatory interactions within discrete chromosomal neighborhoods. Enhancer-promoter contacts occur predominantly within the same TAD, while sequences in different TADs are largely insulated from each other [32] [31]. This organizational principle ensures that regulatory elements appropriately interact with their target genes while preventing ectopic interactions with genes in adjacent domains. When TAD boundaries are disrupted through structural variants or targeted deletions, these insulating properties can be compromised, leading to inappropriate enhancer-promoter interactions and gene misregulation [34] [31].

Evidence from diverse systems indicates that genes within the same TAD tend to be co-regulated and show correlated expression patterns. In rice, for instance, a significant correlation of expression levels has been observed for genes within the same TAD, suggesting they function as genomic domains with shared regulatory features [35]. This organizational principle appears to be a conserved feature of eukaryotic genomes, despite variations in the specific protein machinery involved.

Diagram 1: TAD Organization and Boundary Disruption. Normal TAD architecture (top) constrains enhancer-promoter interactions within domains. Boundary disruption (bottom) can lead to ectopic interactions and gene misregulation.

TAD Pathways: A Methodology for Candidate Gene Prioritization

Conceptual Framework and Implementation

The TAD Pathways method represents an innovative computational approach that addresses a critical challenge in GWAS follow-up studies: how to prioritize causal genes underlying association signals, particularly when those signals fall in non-coding regions [33]. Traditional approaches often default to assigning association signals to the nearest gene, an assumption that frequently leads to incorrect annotations due to the complex nature of gene regulatory landscapes.

The TAD Pathways methodology operates on a fundamental insight: if a GWAS signal falls within a specific TAD, then all genes contained within that same TAD represent plausible candidate genes, as they share the same regulatory neighborhood [33]. The method performs Gene Ontology (GO) analysis on the collective genetic content of TADs containing GWAS signals through a pathway overrepresentation test. This approach leverages the conserved architectural organization of the genome to generate biologically informed hypotheses about which genes and pathways might be driving association signals.

In practice, the method involves several key steps. First, GWAS signals are mapped to their corresponding TADs based on established TAD boundary annotations. Second, all protein-coding genes within these TADs are compiled. Third, pathway enrichment analysis is performed on this gene set to identify biological processes that are statistically overrepresented. This approach effectively expands the search space beyond immediately adjacent genes while constraining it within biologically relevant regulatory domains.

Application Example: Bone Mineral Density

The utility of the TAD Pathways approach was demonstrated in a study of bone mineral density (BMD), where it enabled the re-evaluation of previously suggested gene associations [33]. A GWAS signal at variant rs7932354 had been traditionally assigned to the ARHGAP1 gene based on proximity. However, application of the TAD Pathways method implicated instead the ACP2 gene as a novel regulator of osteoblast metabolism located within the same TAD [33]. This example highlights how 3D genomic information can refine candidate gene prioritization and challenge conventional assignments based solely on linear proximity.

This approach is particularly valuable for studying phenotypes that lack adequate animal models or involve human-specific regulatory mechanisms, such as age at natural menopause or traits associated with imprinted genes [33]. By leveraging the conserved nature of TAD organization across cell types and species, researchers can generate more reliable hypotheses about causal genes even when functional validation is challenging.

Experimental Evidence: In Vivo Validation of TAD Function

Targeted Deletion of TAD Boundaries

Recent research has provided compelling experimental evidence for the functional importance of TAD boundaries in normal genome function and organismal development. A comprehensive study published in Communications Biology used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in mice to individually delete eight different TAD boundaries ranging in size from 11 to 80 kb [34]. These targeted deletions specifically removed all known CTCF and cohesin binding sites in each boundary region while leaving nearby protein-coding genes intact, allowing researchers to assess the specific contribution of boundary sequences to genome function.

The results were striking: 88% (7 of 8) of the boundary deletions caused detectable changes in local 3D chromatin architecture, including merging of adjacent TADs and altered contact frequencies within TADs neighboring the deleted boundary [34]. Perhaps more significantly, 63% (5 of 8) of the boundary deletions were associated with increased embryonic lethality or other developmental phenotypes, demonstrating that these genomic elements are not merely structural features but play essential roles in normal development [34].

Table 2: Phenotypic Consequences of TAD Boundary Deletions in Mice

| Boundary Locus | Size Deleted | 3D Architecture Changes | Viability Phenotype | Additional Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 (Smad3/Smad6) | Not specified | TAD merging | Complete embryonic lethality (E8.5-E10.5) | Partially resorbed embryos |

| B2 | Not specified | TAD merging | ~65% reduction in homozygotes | Not specified |

| B3 | Not specified | TAD merging | 20-37% depletion of homozygotes | Not specified |

| B4 | Not specified | Reduced long-range contacts | 20-37% depletion of homozygotes | Not specified |

| B5 | Not specified | Not specified | 20-37% depletion of homozygotes | Not specified |

| B6 | Not specified | TAD merging | No significant effect | Not specified |

| B7 | Not specified | Reduced long-range contacts | No significant effect | Not specified |

| B8 | Not specified | Loss of insulation | No significant effect | Not specified |

Molecular and Organismal Consequences

The phenotypic severity observed in these boundary deletion experiments appeared to correlate with both the number of CTCF sites affected and the magnitude of resulting changes in chromatin conformation [34]. The most severe organismal phenotypes coincided with pronounced alterations in 3D genome architecture. For example, deletion of a boundary near Smad3/Smad6 caused complete embryonic lethality, while deletion of a boundary near Tbx5/Lhx5 resulted in severe lung malformation [34].

These findings have important implications for clinical genetics. They reinforce the need to carefully consider the potential pathogenicity of noncoding deletions that affect TAD boundaries during genetic screening [34]. As genomic sequencing becomes more routine in clinical practice, understanding the functional consequences of structural variants that disrupt 3D genome organization will be essential for accurate diagnosis and interpretation of variants of uncertain significance.

Advanced Computational Methods: Integrating 3D Genomics with TWAS

The PUMICE Framework

Beyond the TAD Pathways approach, more sophisticated computational methods have emerged that integrate 3D genomic and epigenomic data to enhance gene expression prediction and association testing. PUMICE (Prediction Using Models Informed by Chromatin conformations and Epigenomics) represents one such advanced framework that incorporates both 3D genomic information and epigenomic annotations to improve the accuracy of transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) [36].

The PUMICE method utilizes epigenomic information to prioritize genetic variants likely to have regulatory functions. Specifically, it incorporates four broadly available epigenomic annotation tracks: H3K27ac marks (associated with active enhancers), H3K4me3 marks (associated with active promoters), DNase hypersensitive sites (indicating open chromatin), and CTCF marks (indicating insulator binding) from the ENCODE database [36]. Variants overlapping these annotation tracks are designated as "essential" genetic variants and receive differential treatment in the gene expression prediction model.

A key innovation in PUMICE is its consideration of different definitions for regions harboring cis-regulatory variants, including not only linear windows surrounding gene start and end sites but also 3D genomics-informed regions such as chromatin loops, TADs, domains, and promoter capture Hi-C (pcHi-C) regions [36]. This approach acknowledges that regulatory elements can act over long genomic distances through 3D contacts rather than being constrained by linear proximity.

Performance and Applications

In comprehensive simulations and empirical analyses across 79 complex traits, PUMICE demonstrated superior performance compared to existing methods. The PUMICE+ extension (which combines TWAS results from single- and multi-tissue models) identified 22% more independent novel genes and increased median chi-square statistics values at known loci by 35% compared to the second-best method [36]. Additionally, PUMICE+ achieved the narrowest credible interval sizes, indicating improved fine-mapping resolution for identifying putative causal genes [36].

These advanced methods represent the evolving frontier of integrative approaches that leverage 3D genome organization to bridge the gap between genetic association signals and biological mechanisms. By incorporating multiple layers of genomic annotation and considering the spatial organization of the genome, they provide more powerful and precise frameworks for candidate gene discovery in complex traits.

Diagram 2: Integrative Analysis Workflow for 3D Genomics in Candidate Gene Discovery. Multiple data types are integrated to prioritize candidate genes from GWAS signals using different methodological approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for TAD Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Conformation Technologies | Hi-C, Micro-C, HiChIP, PLAC-seq | Genome-wide mapping of chromatin interactions and TAD identification |

| Epigenomic Profiling Tools | H3K27ac ChIP-seq, H3K4me3 ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, DNase-seq | Mapping active enhancers, promoters, and open chromatin regions |

| Boundary Protein Antibodies | CTCF antibodies, Cohesin (SMC1/3) antibodies | Identification of TAD boundary proteins via ChIP-seq |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, gRNA design tools | Targeted deletion of TAD boundaries for functional validation |

| Computational Tools | Juicer, HiCExplorer, Cooler | Processing and analysis of Hi-C data |

| TAD Callers | Arrowhead, DomainCaller, InsulationScore | Computational identification of TAD boundaries from Hi-C data |

| Visualization Platforms | Juicebox, HiGlass, 3D Genome Browser | Visualization and exploration of chromatin interaction data |

| Reference Datasets | ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics, 4D Nucleome | Reference epigenomic and 3D genome annotations across cell types |

Evolutionary Conservation and Variation

The evolutionary dynamics of TADs provide important insights into their functional significance. Comparative analyses across species reveal a complex pattern of conservation and divergence that reflects both functional constraint and evolutionary flexibility. Studies in Drosophila species separated by approximately 49 million years of evolution show that 30-40% of TADs remain conserved [37]. Similarly, in mammals, a substantial proportion of TAD boundaries are conserved between mouse and human, though estimates vary depending on the specific criteria and methods used [32] [35].

The distribution of structural variants and genome rearrangement breakpoints provides evidence for evolutionary constraint on TAD organization. Analyses across multiple Drosophila species have revealed that chromosomal rearrangement breakpoints are enriched at TAD boundaries but depleted within TADs [37]. This pattern suggests that disruptions within TADs are generally deleterious, while breaks at boundaries may be more tolerated or even serve as substrates for evolutionary innovation.