Genomic Arms Race: Unraveling NBS Domain Gene Diversification in Plant Immunity and Biomedical Potential

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the diversification of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) domain genes, the largest family of plant disease resistance (R) genes.

Genomic Arms Race: Unraveling NBS Domain Gene Diversification in Plant Immunity and Biomedical Potential

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the diversification of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) domain genes, the largest family of plant disease resistance (R) genes. Covering recent advances from 2024-2025, we explore the foundational genomic architecture and evolutionary mechanisms driving the expansion of NBS genes, from mosses to dicots. We detail cutting-edge methodological pipelines for genome-wide identification and characterization, address common challenges in functional analysis, and present case studies validating the role of specific NBS genes in conferring resistance to pathogens like Fusarium wilt and viral diseases. Synthesizing findings from comparative genomics across species including cotton, pepper, and tobacco, this review is tailored for researchers and scientists seeking to understand plant adaptive immunity and its implications for developing disease-resistant crops and novel biomedical strategies.

The Genomic Landscape and Evolutionary Drivers of Plant NBS Gene Families

Domain Architecture and Molecular Function of NBS-LRR Proteins

Nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins, also known as NLRs (NOD-like receptors), constitute the largest and most prominent class of disease resistance (R) proteins in plants, with approximately 80% of cloned R genes encoding members of this family [1] [2]. These proteins function as intracellular immune receptors that form a critical component of the plant's innate immune system, specifically mediating effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [3] [1]. Upon detection of pathogen effector proteins, NBS-LRR activation initiates robust defense signaling, often culminating in a hypersensitive response (HR) characterized by localized programmed cell death at the infection site, thereby restricting pathogen spread [1] [4].

The modular architecture of NBS-LRR proteins typically includes three core domains: a variable N-terminal domain, a central nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain [5] [2]. The N-terminal domain determines association with specific signaling pathways and exists in three major forms: TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor), CC (Coiled-Coil), or RPW8 (Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8) [6] [7]. The NBS domain, also called the NB-ARC (Nucleotide-Binding Adaptor shared by APAF-1, R proteins, and CED-4) domain, belongs to the STAND (Signal Transduction ATPases with Numerous Domains) family of ATPases and functions as a molecular switch regulated by nucleotide (ATP/ADP) binding and hydrolysis [5] [1]. The LRR domain provides versatility in protein-protein interactions and is primarily responsible for pathogen recognition specificity [5] [4] [2].

Beyond the typical tripartite structure, plants also encode "irregular" or "atypical" NBS-LRR proteins that lack one or more domains. These include TN (TIR-NBS), CN (CC-NBS), NL (NBS-LRR), and N (NBS-only) proteins, which may function as adaptors or regulators within immune signaling networks rather than primary pathogen sensors [8] [1].

Structural Domains of NBS-LRR Proteins

The N-terminal Domain: TIR, CC, and RPW8

The N-terminal domain is a key determinant in NBS-LRR classification and signaling pathway specificity, with three major types conferring distinct functional properties.

TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor) Domain:

- Structure and Function: The TIR domain is characterized by four conserved motifs spanning approximately 175 amino acids [5]. It is involved in protein-protein interactions for downstream signal transduction [5]. Some TNL proteins feature an alanine-polyserine motif adjacent to the N-terminal methionine, potentially contributing to protein stability [5].

- Phylogenetic Distribution: TNL proteins are predominantly found in dicotyledonous plants but are completely absent from cereal genomes and some eudicot lineages, indicating lineage-specific loss during evolution [5] [1] [9]. For instance, Salvia miltiorrhiza possesses only two TNL proteins, while Vernicia fordii lacks them entirely [1] [9].

CC (Coiled-Coil) Domain:

- Structure and Function: The CC domain typically spans about 175 amino acids N-terminal to the NBS domain and facilitates protein-protein interactions through its coiled-coil structure [5]. Some CNLs exhibit large N-terminal extensions; for example, the tomato Prf protein contains 1,117 amino acids preceding its NBS domain [5].

- Signaling Specificity: CNLs and TNLs represent distinct evolutionary lineages with different downstream signaling partners, enabling diversified immune response capabilities [5].

RPW8 (Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8) Domain:

- Structure and Function: The RPW8 domain contains a putative N-terminal transmembrane domain and a coiled-coil motif [7]. Unlike TNLs and CNLs that primarily function in pathogen recognition, RNL proteins typically operate downstream in immune signaling cascades, transducing signals from other NBS-LRR sensors [6] [7].

- Evolutionary Origin: The RPW8 domain first emerged in early land plants, specifically in bryophytes like Physcomitrella patens, likely originating de novo from non-coding sequences or through domain divergence after duplication events [7]. RNL proteins are absent in monocot species but have undergone significant expansion in certain dicot families, particularly Rosaceae [1] [7].

The NBS (NB-ARC) Domain

The NBS domain serves as the conserved molecular switch governing NBS-LRR protein activation through nucleotide-dependent conformational changes.

Conserved Motifs and Molecular Mechanism: The NBS domain contains several highly conserved, strictly ordered motifs essential for nucleotide binding and hydrolysis [5] [3]. Key motifs include:

- P-loop (Phosphate-binding loop): Involved in phosphate binding during nucleotide hydrolysis [3].

- RNBS-A, RNBS-B, RNBS-C, RNBS-D (Resistance NBS motifs): Contribute to nucleotide binding specificity and domain stability [5] [3].

- Kinase 2: Participates in nucleotide-dependent conformational changes [2].

- GLPL (Gly-Leu-Pro-Leu, also called Kinase 3): Structural motif important for domain integrity [3] [2].

- MHDV (Met-His-Asp-Val): Critical for nucleotide binding and exchange [3].

Functional Significance: The NBS domain binds and hydrolyzes ATP/GTP, with energy derived from hydrolysis driving conformational changes that regulate downstream signaling [5] [1]. Specific ATP binding and hydrolysis have been experimentally demonstrated for NBS domains of tomato CNLs I2 and Mi [5]. Distinct sequence signatures in RNBS-A, RNBS-C, and RNBS-D motifs differentiate TNL and CNL subfamilies, reflecting their divergent evolutionary paths and signaling mechanisms [5].

The LRR Domain

The C-terminal LRR domain represents the most variable region of NBS-LRR proteins and serves as the primary determinant of recognition specificity.

Structural Characteristics:

- Repeat Organization: LRR domains typically consist of multiple 20-30 amino acid repeats that form solenoid-like structures with solvent-exposed β-sheets, creating extensive protein interaction surfaces [5] [4].

- Sequence Diversity: The number of LRR repeats varies significantly among proteins, averaging approximately 14 repeats per protein with substantial sequence variation [5]. This diversity generates immense recognition potential; in Arabidopsis thaliana alone, the theoretical combinatorial variability exceeds 9×10^11 different LRR configurations [5].

Functional Mechanisms: The LRR domain enables specific pathogen recognition through multiple strategies [8]:

- Direct Interaction: Binding directly to pathogen effector proteins.

- Guard Mechanism: Monitoring the status of host proteins targeted by pathogen effectors.

- Decoy Function: Using integrated domains that mimic pathogen targets to detect effector activity.

Evolutionary Dynamics: The LRR domain evolves under diversifying selection, particularly at solvent-exposed residues, maintaining variation critical for adapting to evolving pathogen challenges [5]. Unequal crossing-over and gene conversion events generate significant variation in repeat number, position, and orientation, further expanding recognition capabilities [5].

Table 1: Key Domains of NBS-LRR Proteins and Their Characteristics

| Domain | Key Features | Conserved Motifs | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIR | ~175 amino acids, 4 conserved motifs | TIR-1, TIR-2, TIR-3, TIR-4 | Protein-protein interaction, signaling initiation |

| CC | ~175 amino acids, coiled-coil structure | Variable, sometimes large unique extensions | Protein oligomerization, signaling transduction |

| RPW8 | N-terminal TM, CC motif | Coiled-coil motif | Downstream signal transduction, broad-spectrum resistance |

| NBS | ~300 amino acids, STAND ATPase | P-loop, RNBS-A, RNBS-B, RNBS-C, RNBS-D, Kinase-2, GLPL, MHDV | Molecular switch, ATP/GTP binding/hydrolysis |

| LRR | Multiple 20-30 aa repeats, β-sheet structure | Highly variable, leucine-rich | Pathogen recognition, protein-protein interaction |

Genomic Distribution and Evolutionary Patterns

Genomic Organization and Family Size

NBS-LRR genes represent one of the largest and most dynamic gene families in plant genomes, exhibiting remarkable variation in family size across species.

Family Size Variation: The number of NBS-LRR genes varies substantially among plant species, reflecting diverse evolutionary histories and selective pressures:

- Arabidopsis thaliana: ~150 genes [5]

- Oryza sativa (rice): ~400-500 genes [5] [10]

- Nicotiana benthamiana: 156 genes [8]

- Solanum tuberosum (potato): ~447 genes [1]

- Salvia miltiorrhiza: 196 NBS-domain genes (62 with complete N-terminal and LRR domains) [1]

- Rosa chinensis: 96 intact TNL genes [3]

- Manihot esculenta (cassava): 228 NBS-LRR genes plus 99 partial NBS genes [4]

- Vernicia fordii: 90 NBS-LRR genes; Vernicia montana: 149 NBS-LRR genes [9]

- Capsicum annuum (pepper): 252 NBS-LRR genes [2]

This variation results from lineage-specific gene expansions and contractions driven by diverse selective pressures from pathogen communities [6].

Genomic Clustering: NBS-LRR genes frequently occur in clustered arrangements, with approximately 54-63% residing in tandem arrays across plant genomes [4] [2]. For example:

- In pepper, 136 NBS-LRR genes (54% of the family) form 47 distinct clusters, with chromosome 3 containing the largest cluster of 8 genes [2].

- In cassava, 63% of 327 R genes are organized into 39 clusters distributed across chromosomes [4]. These clusters are often homogeneous, containing recently duplicated paralogs, though heterogeneous clusters with phylogenetically diverse members also occur [4]. Clustered organization facilitates rapid evolution through unequal crossing-over, gene conversion, and ectopic recombination, generating novel recognition specificities [5] [4].

Evolutionary Dynamics and Mechanisms

NBS-LRR gene families evolve through complex birth-and-death processes involving gene duplication, diversifying selection, and frequent gene loss.

Evolutionary Patterns Across Plant Lineages: Comparative genomics reveals distinct evolutionary trajectories in different plant families [6]:

- Rosaceae: Multiple patterns including "first expansion and then contraction" (Rubus occidentalis, Potentilla micrantha, Fragaria iinumae), "continuous expansion" (Rosa chinensis), and "early sharp expanding to abrupt shrinking" (Prunus species, Maleae species) [6].

- Poaceae: A general "contracting" pattern observed in rice, maize, sorghum, and Brachypodium distachyon [6].

- Fabaceae: A "consistently expanding" pattern in Medicago truncatula, pigeon pea, common bean, and soybean [6].

- Solanaceae: Diverse patterns with potato exhibiting "consistent expansion," tomato showing "expansion followed by contraction," and pepper demonstrating a "shrinking" pattern [6] [2].

Molecular Evolutionary Mechanisms:

- Birth-and-Death Evolution: New genes are created by duplication while others are eliminated by pseudogenization or deletion, maintaining family size equilibrium over evolutionary time [5] [2].

- Diversifying Selection: Strong positive selection acts on solvent-exposed residues of the LRR domain, indicated by elevated ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous nucleotide substitutions (dN/dS) [5].

- Domain-Specific Evolutionary Rates: Different protein domains experience distinct selective pressures, with LRR domains evolving rapidly under positive selection, while NBS domains are predominantly under purifying selection with occasional positive selection [5].

- Frequent Domain Rearrangements: Domain fusions, fissions, and losses generate novel architectural configurations, such as the de novo origin of the RPW8 domain in early land plants and its subsequent fusion with NBS domains [7].

Table 2: NBS-LRR Gene Family Size and Composition Across Selected Plant Species

| Plant Species | Total NBS genes | TNL | CNL | RNL | Atypical | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | ~150 | 62 | 88 | 7 | 58 | [5] [10] |

| Oryza sativa (rice) | ~400-500 | 0 | ~500 | 0 | - | [5] [1] |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | 156 | 5 | 25 | - | 124 | [8] |

| Solanum tuberosum (potato) | ~447 | - | - | - | - | [1] |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza | 196 | 2 | 61 | 1 | 132 | [1] |

| Rosa chinensis | 96 (TNL only) | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [3] |

| Manihot esculenta (cassava) | 327 | 34 | 128 | - | 165 | [4] |

| Capsicum annuum (pepper) | 252 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 245 | [2] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genome-Wide Identification of NBS-LRR Genes

Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Search Protocol:

- Domain Profile Acquisition: Obtain the HMM profile for the NBS (NB-ARC) domain (PF00931) from the Pfam database [8] [4].

- Initial Gene Identification: Perform HMMER search against the target proteome using conservative E-value cutoff (typically E-value < 1×10â»Â²â°) [8] [4].

- Candidate Verification: Validate identified sequences using Pfam, SMART, and NCBI-CDD databases to confirm presence of complete NBS domains (E-value < 0.01) [8] [4].

- Domain Architecture Annotation: Identify additional domains (TIR, CC, RPW8, LRR) using:

Phylogenetic Analysis Workflow:

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Extract NBS domain regions and align using ClustalW or MAFFT under default parameters [8] [4].

- Model Selection: Determine best-fit substitution model (e.g., Whelan and Goldman + freq. model) using model selection tools [8].

- Tree Construction: Build maximum likelihood phylogeny with bootstrap validation (typically 1000 replicates) using MEGA or FastTreeMP [8] [10].

- Subfamily Classification: Categorize sequences into TNL, CNL, and RNL clades based on phylogenetic positioning and domain composition [8] [6].

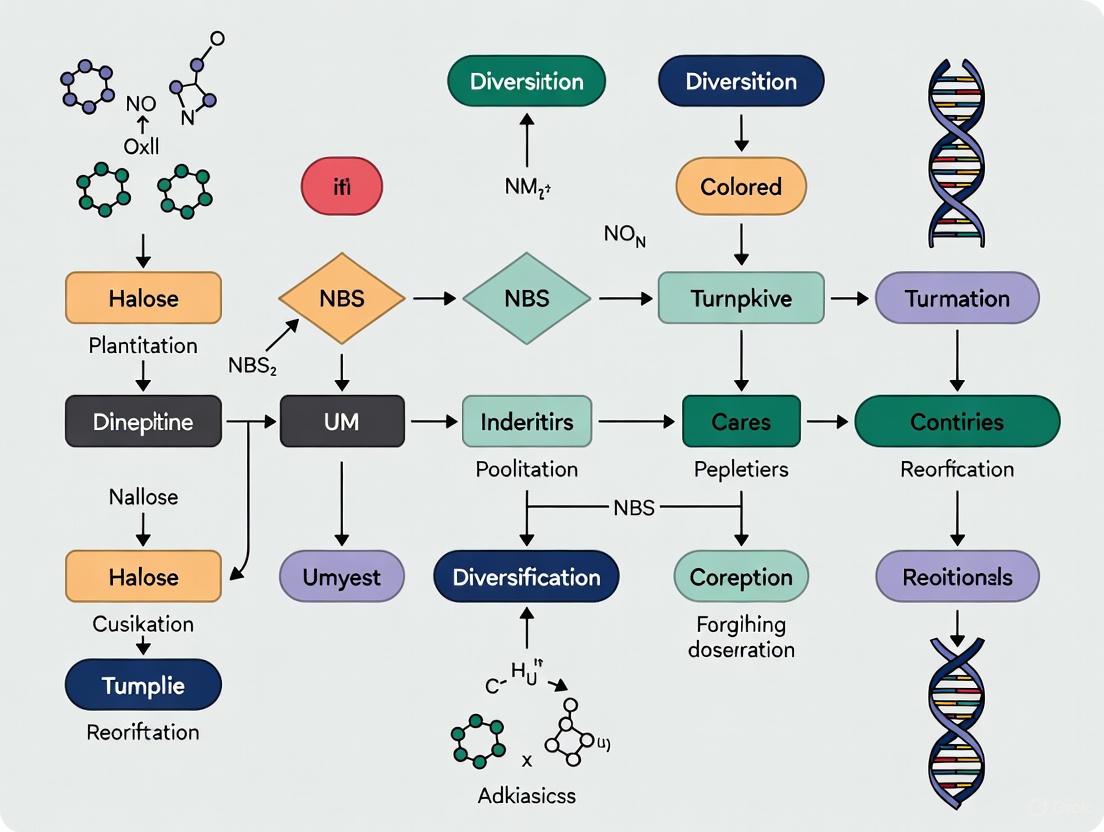

Figure 1: Genome-wide identification workflow for NBS-LRR genes

Functional Characterization Methods

Expression Analysis:

- Transcriptome Profiling: Utilize RNA-seq data to examine tissue-specific expression patterns and responses to biotic/abiotic stresses, calculating FPKM values for quantitative comparisons [10] [3].

- qRT-PCR Validation: Design gene-specific primers to verify expression patterns identified in transcriptome data, particularly under pathogen challenge or hormone treatments [3].

- Promoter Analysis: Identify cis-regulatory elements in 1500 bp upstream regions using PlantCARE database, focusing on hormone-responsive and stress-related elements [8] [3].

Functional Validation:

- Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS):

- Design specific fragment (300-500 bp) from target NBS-LRR gene [10] [9].

- Clone into TRV-based VIGS vector (e.g., pTRV1/pTRV2 system) [9].

- Agroinfiltrate into plant leaves using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 [9].

- Monitor silencing efficiency 2-3 weeks post-infiltration and challenge with target pathogen [9].

- Assess disease symptoms and measure pathogen biomass to quantify resistance changes [9].

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies:

Genetic Transformation:

Figure 2: Functional characterization pipeline for NBS-LRR genes

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NBS-LRR Gene Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMM Profiles | PF00931 (NB-ARC), PF01582 (TIR), PF05659 (RPW8) | Domain identification and gene family annotation | [8] [4] |

| Software Tools | HMMER, MEME, ClustalW, MEGA, TBtools | Sequence analysis, motif discovery, phylogenetics | [8] [4] |

| Genome Databases | Phytozome, NCBI, Plaza, Rosaceae.org, CottonFGD | Genomic data retrieval and comparative analysis | [10] [6] |

| VIGS Vectors | TRV-based pTRV1/pTRV2 system | Functional validation through gene silencing | [10] [9] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | GV3101, LBA4404 | Plant transformation and VIGS delivery | [9] |

| Expression Databases | IPF Database, CottonFGD, NCBI BioProjects | Expression pattern analysis across tissues/stresses | [10] |

| Pathogen Isolates | Fusarium oxysporum, Marssonina rosae, TMV | Disease phenotyping and resistance assays | [3] [9] |

NBS-LRR proteins represent a sophisticated plant immune receptor system characterized by modular domain architecture, diverse recognition specificities, and dynamic evolutionary patterns. Their conserved NBS domain functions as a molecular switch regulated by nucleotide-dependent conformational changes, while variable LRR and N-terminal domains provide recognition specificity and signaling pathway diversification. The intricate genomic organization of NBS-LRR genes into tandem clusters facilitates rapid evolution through recombination and duplication events, enabling plants to maintain effective immune recognition despite rapidly evolving pathogen populations. Continuing research on NBS-LRR protein structure, function, and evolution provides critical insights for developing durable disease resistance in crop species through marker-assisted breeding and biotechnological approaches.

The evolutionary history of land plants, spanning over 500 million years, is characterized by profound genomic changes that underlie their adaptation to diverse ecological niches. Among the most dynamic components of plant genomes are Nucleotide-Binding Site-Leucine Rich Repeat (NBS-LRR) genes, which constitute the largest family of disease resistance (R) genes in plants. These genes encode intracellular immune receptors that recognize pathogen effectors and activate effector-triggered immunity (ETI), playing a crucial role in plant survival and evolutionary success [11] [10]. The diversification of these genes follows distinct evolutionary trajectories across different plant lineages, from early-diverging bryophytes to recently evolved angiosperms, revealing a complex pattern of lineage-specific expansion and loss that mirrors the adaptation challenges faced by each plant group.

This whitepaper examines the evolutionary patterns of NBS domain genes across the plant kingdom, focusing on the mechanistic drivers of gene family diversification and its functional consequences for plant immunity. Understanding these patterns provides fundamental insights into plant evolutionary biology and offers potential applications for crop improvement through the engineering of disease resistance.

Evolutionary Patterns of NBS Genes Across Plant Lineages

Genomic Diversity in Early Land Plants

Recent genomic analyses have revolutionized our understanding of bryophyte evolution. A comprehensive super-pangenome analysis incorporating 123 newly sequenced bryophyte genomes reveals that despite their morphological simplicity, bryophytes possess a substantially larger gene family space than vascular plants, with 637,597 versus 373,581 nonredundant gene families [12] [13] [14]. This expanded genetic toolkit includes unique immune receptors that have facilitated their adaptation to diverse habitats, including extreme environments.

Bryophytes exhibit a notably different pattern of NBS-LRR gene evolution compared to vascular plants. While flowering plants often possess hundreds of NBS-LRR genes, the bryophyte Physcomitrella patens contains only approximately 25 NLRs (NBS-LRR genes), and the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii has a mere 2 NLRs [10]. This suggests that the massive expansion of NLR repertoires occurred primarily after the divergence of vascular plants from the bryophyte lineage.

Table 1: NBS-LRR Gene Distribution Across Major Plant Lineages

| Plant Lineage | Representative Species | Approximate NBS-LRR Count | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bryophytes | Physcomitrella patens | ~25 | Minimal expansion; lineage-specific Kin-NLRs and Hyd-NLRs |

| Lycophytes | Selaginella moellendorffii | ~2 | Drastic contraction |

| Ferns | Pteris vittata | Diverse repertoire | TIR-NLRs, CC-NLRs, RPW8-NLRs; subfamilies lost in angiosperms |

| Monocots | Oryza sativa (rice) | ~500 | Loss of TNL genes; dominance of CNL-type |

| Eudicots | Arabidopsis thaliana | ~210 | Both TNL and CNL types present |

Lineage-Specific Patterns in Angiosperms

Within angiosperms, NBS-LRR genes exhibit remarkable variation in copy number and evolutionary patterns. A genome-wide analysis of 12 Rosaceae species identified 2,188 NBS-LRR genes with distinct evolutionary trajectories across different genera [6]. These patterns include:

- "Continuous expansion" in Rosa chinensis

- "First expansion and then contraction" in Rubus occidentalis, Potentilla micrantha, and Fragaria iinumae

- "Expansion followed by contraction, then further expansion" in F. vesca

- "Early sharp expanding to abrupt shrinking" in three Prunus species and three Maleae species

In orchids, another distinct evolutionary pattern emerges. Analysis of 655 NBS genes from seven orchid species reveals significant degeneration of NBS-LRR genes, with type changing and NB-ARC domain degeneration being common [15]. Notably, no TNL-type genes were identified in any of the six orchids studied, consistent with the absence of this subclass in most monocots.

Genomic and Experimental Methodologies for Studying NBS Gene Evolution

Genome-Wide Identification and Classification

The standard workflow for identifying and classifying NBS domain genes involves multiple bioinformatic approaches:

Identification Workflow:

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain whole genome sequences and annotation files from databases such as NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza, Rosaceae Genome Database, or other lineage-specific resources [10] [6].

- Candidate Gene Identification: Perform dual-method screening using:

- BLASTP search with known NBS proteins as queries (e-value threshold typically 1.0)

- HMMER search with the NB-ARC domain hidden Markov model (PF00931) from Pfam database

- Domain Verification: Confirm the presence of characteristic domains using:

- Pfam database for NB-ARC (PF00931) and N-terminal domains (TIR: PF01582, CC: PF18052, RPW8: PF05659)

- NCBI-CDD search for additional domain validation

- Classification: Categorize validated NBS-LRR genes into subclasses (TNL, CNL, RNL) based on N-terminal domains [10] [6].

Evolutionary Analysis Methods

Orthogroup and Phylogenetic Analysis:

- Orthogroup Inference: Use OrthoFinder v2.5.1 with DIAMOND for sequence similarity searches and MCL clustering algorithm to identify orthogroups [10].

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Employ maximum likelihood algorithms (FastTreeMP) with bootstrap validation (typically 1000 replicates) for phylogenetic tree construction [15].

- Gene Family Evolution: Map gene gain/loss events using computational frameworks like DendroBLAST to infer evolutionary trajectories across lineages [10].

Expression and Functional Analysis:

- Transcriptomic Profiling: Analyze RNA-seq data from various tissues and stress conditions to determine expression patterns.

- Functional Validation: Implement virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) to confirm gene function, as demonstrated in the validation of GaNBS (OG2) in resistant cotton [10].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for NBS Gene Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| NB-ARC HMM Profile (PF00931) | Identification of NBS domain genes | Initial screening of candidate NBS genes |

| OrthoFinder v2.5.1 | Orthogroup inference and comparative genomics | Evolutionary analysis across multiple species |

| MEME Suite | Conserved motif analysis | Identification of NBS domain sub-structures |

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Functional validation of candidate genes | Testing role of GaNBS in cotton disease resistance |

| Salicylic acid treatment | Induction of defense response pathways | Studying NBS-LRR gene expression in Dendrobium |

Molecular Mechanisms Driving NBS Gene Diversification

Gene Duplication and Divergence

The expansion and contraction of NBS gene families are primarily driven by various duplication mechanisms:

- Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD): Provides raw genetic material for neofunctionalization, particularly important in mosses where successive WGDs have contributed to gene family innovation since the early Cretaceous (~100 Mya) [12].

- Tandem Duplications: Frequently observed in NBS-LRR gene clusters, leading to rapid expansion of specific subfamilies, as documented in grass species where NBS-LRR genes show high aggregation and duplication due to local duplications [15].

- Small-Scale Duplications (SSD): Including segmental and transposon-mediated duplications, contributing to the birth of new resistance specificities [10].

Following duplication, NBS genes undergo diversifying selection, particularly in the LRR domain, which creates novel resistance specificities as part of the host's evolutionary arms race with pathogens [16].

Regulatory Evolution and miRNA-Mediated Control

A sophisticated regulatory system involving microRNAs (miRNAs) has evolved to control NBS-LRR gene expression. This system helps balance the benefits of pathogen recognition against the fitness costs of maintaining large NBS-LRR repertoires [11]. Key aspects include:

- Lineage-Specific miRNA Emergence: New miRNAs periodically emerge from duplicated NBS-LRR sequences, predominantly targeting conserved protein motifs like the P-loop region [11].

- Expression Regulation: miRNAs typically target highly duplicated NBS-LRRs, while heterogeneous NBS-LRR families are less frequently targeted, as observed in Poaceae and Brassicaceae [11].

- Compensatory Evolution: Nucleotide diversity in the wobble position of codons in miRNA target sites drives miRNA diversification, suggesting a co-evolutionary model between NBS-LRRs and their regulatory miRNAs [11].

Comparative Analysis of NBS Gene Evolution in Major Plant Lineages

Bryophytes: Minimal Expansion with Lineage-Specific Innovations

Despite their extensive gene family space overall, bryophytes maintain relatively small NBS-LRR repertoires. However, they possess unique immune receptor types not found in vascular plants, including lineage-specific kinase NLRs (Kin-NLRs) and α/β-hydrolase NLRs (Hyd-NLRs) [17]. This suggests that while bryophytes have not extensively expanded classical NBS-LRR genes, they have evolved alternative immune receptor architectures.

The large gene family space in bryophytes originates from extensive new gene formation and continuous horizontal transfer of microbial genes over their long evolutionary history [12]. These newly acquired genes include novel physiological innovations like unique immune receptors that likely facilitated their spread across different biomes.

Ferns: Intermediate Diversity with Ancestral Features

Ferns represent a critical transitional group in plant immunity evolution, possessing a diverse repertoire of putative immune receptors that include TIR-NLRs, CC-NLRs, and RPW8-NLRs, along with non-canonical NLRs and NLR sub-families lost in angiosperms [17]. Genomic mining indicates that ferns encode numerous receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and receptor-like proteins (RLPs) resembling those required for cell-surface immunity in angiosperms, suggesting conservation of core immune components across vascular plants.

Interestingly, fern gametophytes and sporophytes show differential responses to pathogens, indicating that life stage-specific regulation of immunity represents an important layer of disease resistance in these plants [17].

Angiosperms: Extensive Diversification with Lineage-Specific Patterns

Angiosperms exhibit the most dynamic evolution of NBS-LRR genes, with several distinct patterns emerging:

Monocots vs. Eudicots Divergence:

- Monocots: Generally lack TNL-type genes, potentially driven by NRG1/SAG101 pathway deficiency [15]. For example, comprehensive analysis of six orchid species identified no TNL-type genes [15].

- Eudicots: Maintain both TNL and CNL types, with varying ratios across families.

Family-Specific Evolutionary Patterns:

- Rosaceae: Exhibit at least four distinct evolutionary patterns across different genera, from continuous expansion to contraction-expansion-contraction dynamics [6].

- Orchidaceae: Show significant degeneration of NBS-LRR genes, with type changing and NB-ARC domain degeneration being common evolutionary mechanisms [15].

- Poaceae: Display a "contracting" pattern in species like maize, sorghum, and Brachypodium distachyon [6].

Table 3: Evolutionary Patterns of NBS-LRR Genes Across Angiosperm Families

| Plant Family | Representative Species | Evolutionary Pattern | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosaceae | Rosa chinensis | Continuous expansion | High NBS-LRR diversity |

| Rosaceae | Prunus species | Early expansion to abrupt shrinking | Rapid evolution followed by stabilization |

| Solanaceae | Potato | Consistent expansion | Large NBS-LRR repertoires |

| Solanaceae | Tomato | Expansion followed by contraction | Moderate NBS-LRR numbers |

| Solanaceae | Pepper | Shrinking | Limited NBS-LRR diversity |

| Fabaceae | Medicago, soybean | Consistent expansion | Large and diverse NBS-LRR collections |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumber, melon | Frequent lineage losses | Low copy number |

The evolutionary history of NBS domain genes across land plants reveals a complex tapestry of lineage-specific expansion and loss events driven by diverse molecular mechanisms. From the minimal but innovative immune repertoires of bryophytes to the highly diversified and dynamically evolving NBS-LRR genes of angiosperms, each plant lineage has forged distinct evolutionary paths in response to pathogen pressure.

These patterns reflect alternating cycles of expansion through various duplication mechanisms and contraction through pseudogenization and gene loss, shaped by the balance between selective advantages of new resistance specificities and the fitness costs of maintaining large immune receptor repertoires. The recent discovery of bryophytes' extensive gene family space alongside their limited NBS-LRR expansion suggests that different plant lineages have evolved alternative strategies for pathogen defense, with profound implications for understanding plant immunity evolution.

Future research directions should include more comprehensive sampling of early-diverging plant lineages, functional characterization of lineage-specific immune receptors, and exploration of how different evolutionary trajectories contribute to disease resistance outcomes. Such investigations will not only deepen our understanding of plant evolution but may also reveal novel genetic resources for engineering disease resistance in crop plants.

Plant immunity relies heavily on a diverse and sophisticated arsenal of intracellular immune receptors, predominantly the nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins, also known as NLR (NOD-like receptor) proteins [18]. These proteins are modular and function as key sentinels in effector-triggered immunity (ETI), directly or indirectly recognizing pathogen-derived effector molecules and initiating robust defense responses, often including a form of programmed cell death known as the hypersensitive response (HR) [19]. The central nucleus of these proteins is the NBS (Nucleotide-Binding Site) domain, also referred to as the NB-ARC (Nucleotide-Binding Adaptor shared with APAF-1, R proteins, and CED-4) domain [10]. This domain is evolutionarily ancient and is responsible for nucleotide (ATP/ADP) binding and hydrolysis, which acts as a molecular switch for activation and signaling [19] [18].

The diversification of NBS domain genes is a cornerstone of plant adaptation, driven by evolutionary pressures from rapidly evolving pathogens. This diversification occurs through mechanisms such as whole-genome duplication (WGD), small-scale duplications (including tandem, segmental, and transposon-mediated duplications), and domain shuffling, leading to an enormous variety of domain architectures [10]. While the TNL (TIR-NBS-LRR) and CNL (CC-NBS-LRR) classifications represent the two major canonical classes, recent genomic studies have uncovered a surprising array of non-canonical architectures that expand the functional repertoire of plant immune receptors [10]. This whitepaper details the major classification systems based on domain architecture, framing this diversity within the broader context of NBS domain gene evolution and its critical implications for plant pathogen resistance.

Canonical NBS-LRR Architectures: The Two Major Classes

The primary classification of NBS-LRR proteins is defined by the structure of their N-terminal domains. This domain is a key determinant in downstream signaling pathway activation.

CC-NBS-LRR (CNL) Proteins

- N-terminal Domain: A predicted Coiled-Coil (CC) domain [19] [10].

- Prevalence: CNLs are one of the most abundant groups of NBS-LRR proteins in flowering plants. For example, a broad genomic survey identified 70,737 CNL genes across 304 angiosperm genomes, significantly outnumbering TNLs [10].

- Function: The CC domain is often involved in signaling and protein-protein interactions. In the potato Rx protein (a CNL), the CC domain is sufficient to complement a version of the protein lacking this domain, restoring function [19].

TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) Proteins

- N-terminal Domain: A Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) domain [10].

- Prevalence: TNLs are less common than CNLs in many angiosperms, with the same survey reporting 18,727 TNL genes [10]. They are absent from most monocot genomes [10].

- Function: The TIR domain is believed to possess enzymatic activity and is crucial for initiating specific signaling cascades. TIR domains can function in pathogen recognition and are essential for the HR cell death response [19].

The Third Subclass: RPW8-NBS-LRR (RNL) Proteins

A third, smaller subclass of NLRs is characterized by an N-terminal Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8 (RPW8) domain [10]. These RNL proteins often play a conserved role as helper components in the immune network, facilitating the signaling of other sensor NLRs [10].

Table 1: Canonical NBS-LRR Protein Classes and Their Characteristics

| Class | N-terminal Domain | Central Domain | C-terminal Domain | Prevalence | Proposed Signaling Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNL | Coiled-Coil (CC) | NBS (NB-ARC) | LRR | High in angiosperms; ~70,737 genes in a survey of 304 species [10] | Activates specific downstream signaling pathways; can function with CC domain in trans [19] |

| TNL | TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor) | NBS (NB-ARC) | LRR | Lower than CNLs in many angiosperms; ~18,707 genes in a survey of 304 species [10] | Activates distinct defense pathways; involved in HR cell death [19] |

| RNL | RPW8 | NBS (NB-ARC) | LRR | Smaller, conserved subclass [10] | Often acts as a helper component in immune signaling [10] |

Beyond CNL and TNL: A Spectrum of Novel Domain Combinations

Genome-wide analyses have revealed that the architectural landscape of NBS-domain-containing genes is far more complex than the canonical CNL/TNL/RNL models. A recent study identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species, which were classified into 168 distinct domain architecture classes [10]. This indicates immense diversification and the evolution of numerous non-canonical resistance genes.

Common Non-Canonical Architectures

Many common variants involve the presence or absence of the canonical domains:

- NBS-LRR: Proteins lacking a defined N-terminal TIR or CC domain.

- TIR-NBS: Proteins lacking the C-terminal LRR domain.

- CC-NBS: Proteins with a CC and NBS domain but no LRR.

- Standalone NBS: Proteins consisting primarily of the NBS domain.

Species-Specific and Complex Architectures

The discovery of species-specific domain patterns highlights the dynamic evolution of this gene family. Examples identified include [10]:

- TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1

- TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf

- Sugar_tr-NBS

These novel combinations likely confer new functional specificities, potentially linking pathogen recognition to other metabolic or signaling processes within the cell. The LRR domain, in particular, is the most variable region and is a major determinant of recognition specificity [19].

Table 2: Examples of Non-Canonical and Complex NBS Domain Architectures

| Architecture Class | Domain Composition | Significance / Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|

| TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1 | TIR, NBS, TIR, two Cupin_1 domains | Suggests integration of immune signaling with secondary metabolic processes. |

| TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf | TIR, NBS, Prenyltransferase domain | Potential for direct modification of signaling molecules via prenylation. |

| Sugar_tr-NBS | Sugar transporter, NBS | Links nutrient/sugar sensing directly to immune activation. |

| NBS-LRR | NBS, LRR | LRR for recognition, but uses an unknown N-terminal signaling mechanism. |

| TIR-NBS | TIR, NBS | May represent a signaling-optimized protein that relies on other components for recognition. |

Experimental Dissection of NBS Protein Architecture and Function

Understanding the function of these diverse architectures requires robust experimental methodologies. Research on the potato Rx protein, a canonical CNL that confers resistance to Potato Virus X (PVX), provides a classic paradigm for dissecting the functional roles of NBS protein domains.

Key Experimental Protocol: Domain Complementation and Protein Interaction Assays

The following methodology, derived from seminal work on the Rx protein, is used to test the functional autonomy and interdependence of NBS protein domains [19].

1. Objective: To determine if different domains of an NBS-LRR protein can function in trans (as separate molecules) and to map the physical interactions between these domains.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Plasmid Constructs: Epitope-tagged (e.g., HA-tag) constructs for full-length Rx and its separate domains (CC, NBS, LRR, CC-NBS, NBS-LRR, ARC-LRR) in appropriate expression vectors [19].

- Plant Material: Leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana for transient expression via Agrobacterium infiltration.

- Elicitor: Plasmid expressing the PVX coat protein (CP), the specific elicitor for Rx [19].

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Reagents: Antibodies against the epitope tags, protein A/G beads, lysis, and wash buffers.

- HR Cell Death Assay Reagents: Tools for visual documentation and scoring of the hypersensitive response.

3. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1: Transient Co-expression in N. benthamiana.

- Co-infiltrate Agrobacterium strains containing different combinations of domain constructs (e.g., CC-NBS + LRR; CC + NBS-LRR) with and without the PVX CP elicitor.

- Step 2: Functional Complementation Assay.

- Monitor infiltrated leaf patches for the appearance of a hypersensitive response (HR), a rapid cell death indicating successful immune activation.

- Key Finding: Co-expression of CC-NBS and LRR as separate polypeptides resulted in a CP-dependent HR, demonstrating functional complementation in trans [19].

- Step 3: Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) for Physical Interaction.

- Extract proteins from leaf tissue expressing the domain combinations.

- Immunoprecipitate one tagged domain and probe for the co-precipitation of the other tagged partner.

- Key Finding: CC-NBS physically interacted with LRR, and CC interacted with NBS-LRR. These interactions were disrupted in the presence of the CP elicitor [19].

- Step 4: Mutational Analysis.

- Introduce point mutations (e.g., in the P-loop motif of the NBS domain) to assess the requirement for nucleotide binding in domain interactions and function.

4. Interpretation: The Rx study demonstrated that the intact protein maintains an auto-inhibited state through intramolecular interactions (e.g., CC with NBS-LRR, and CC-NBS with LRR). Pathogen perception is proposed to cause sequential disruption of these interactions, leading to activation [19]. This experimental framework can be applied to novel domain architectures to determine if and how their unique domains participate in this regulation and signaling.

Genome-Wide Identification Workflow

For the initial identification and annotation of NBS-encoding genes on a genomic scale, bioinformatic pipelines like NLGenomeSweeper are essential [18]. This tool uses the BLAST suite to identify the conserved NB-ARC domain and returns candidate gene locations with InterProScan ORF and domain annotations for manual curation, with a focus on complete functional genes and relatively intact pseudogenes [18].

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for identifying and functionally characterizing NBS domain genes, from genomic discovery to experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Research into NBS domain gene diversification relies on a specific set of reagents and methodologies. The following table details key resources for studies in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for NBS Gene Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Description / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Assemblies & Databases | NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza databases; ANNA: Angiosperm NLR Atlas [10] | Source of genomic sequences and curated annotations for identification and comparative genomics. |

| Bioinformatic Tools | NLGenomeSweeper [18], PfamScan [10], OrthoFinder [10] | Identifying NBS genes, defining domain architecture, and determining evolutionary relationships (orthogroups). |

| Cloning & Expression Vectors | Epitope-tagged (e.g., HA) constructs in binary vectors for Agrobacterium [19] | Transient or stable expression of full-length and truncated NBS proteins in plant cells. |

| Plant Transformation Systems | Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation in N. benthamiana [19] | Rapid functional assays for cell death and protein interaction. |

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | VIGS vectors targeting candidate NBS genes [10] | Functional validation through knockdown of gene expression and subsequent pathogen challenge. |

| Pathogen/Elicitor Stocks | Purified pathogen effectors or clones (e.g., PVX Coat Protein) [19] | Specific activation of NBS-mediated immune responses for functional assays. |

| Antibodies for Protein Analysis | Anti-HA, Anti-Myc, etc. for Western Blot and Co-IP [19] | Detection and immunoprecipitation of tagged NBS proteins and their interaction partners. |

| Flufenoxuron | Flufenoxuron | Benzoylurea Chitin Synthesis Inhibitor | Flufenoxuron is a benzoylurea insect growth regulator for agricultural research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Tma-dph | Tma-dph | Fluorescent Membrane Probe | Tma-dph is a hydrophobic fluorescent probe for studying membrane fluidity and dynamics. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The classification of plant NBS domain genes has evolved from a simple CNL/TNL dichotomy to a complex spectrum encompassing 168+ architectural classes. This diversity, driven by relentless pathogen pressure, is a hallmark of the plant immune system's evolutionary strategy. Canonical CNL and TNL architectures, with their distinct signaling pathways, form the backbone of intracellular immunity, while the explosion of non-canonical forms—from truncated variants to complex fusions with domains like Cupin or Prenyltransferase—suggests a massive functional innovation and diversification [10].

Framing this architectural diversity within the broader thesis of NBS gene evolution reveals a dynamic genetic landscape. The large NLR repertoires in flowering plants, which can number in the hundreds per genome, starkly contrast with the few dozen found in ancestral lineages like bryophytes, indicating a massive expansion coinciding with plant terrestrialization and radiation [10]. This expansion is fueled by duplication mechanisms, with gene families evolving through whole-genome duplications (WGD) seldom undergoing small-scale duplications (SSD), suggesting separate modes of evolution [10]. Furthermore, emerging evidence points to a role for microRNAs in the transcriptional suppression of NLRs, which may offset the fitness costs of maintaining such large repertoires, thereby enabling their persistence and diversification [10].

Understanding this intricate diversity is not merely an academic exercise. It is fundamental for future crop improvement. By deciphering the genetic codes of resistance, from the core NBS domain to the highly variable LRR and the novel integrated domains, researchers can identify new sources of disease resistance. The experimental frameworks and tools outlined here provide a pathway to functionally validate these genes. Ultimately, this knowledge empowers the development of durable disease-resistant crops through molecular breeding or biotechnological approaches, leveraging the natural architectural diversity of NBS genes to safeguard global food security.

The Impact of Whole-Genome and Tandem Duplication Events on Repertoire Size

The expansion of gene repertoires is a fundamental process in evolutionary genomics, particularly for gene families central to plant adaptation and defense. Within the context of NBS domain gene diversification in plants, the mechanisms of whole-genome duplication (WGD) and tandem duplication (TD) represent two primary drivers of repertoire size evolution. These duplication mechanisms operate at different genomic scales and temporal frequencies, resulting in distinct patterns of gene retention, functional divergence, and evolutionary dynamics [20] [21]. Understanding how these processes collectively and independently shape the NBS domain gene repertoire provides crucial insights into plant genome evolution and the molecular basis of disease resistance.

Comparative genomic analyses across diverse plant lineages have revealed that duplicate genes are exceptionally prevalent in plant genomes, with an average of 65% of annotated genes having a duplicate copy [20]. The proportion of duplicated genes varies substantially across species, ranging from approximately 45.5% in the bryophyte Physcomitrella patens to 84.4% in apple (Malus domestica) [20]. This abundance of genetic redundancy provides the raw material for evolutionary innovation, with different duplication mechanisms favoring the retention of distinct functional categories of genes that ultimately shape the adaptive landscape of plant genomes.

Mechanisms of Gene Duplication and Their Genomic Signatures

Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD)

WGD, or polyploidization, represents the most dramatic mechanism of gene duplication, simultaneously doubling the entire gene complement of an organism. Plant genomes have experienced recurrent WGD events throughout their evolutionary history, with some lineages exhibiting multiple rounds of polyploidization [20]. These events create massive genomic redundancy and provide opportunities for substantial evolutionary innovation. Evidence from myosin motor protein analyses supports at least 23 documented WGDs across angiosperm evolution, with several additional events predicted in specific lineages including Manihot esculenta, Nicotiana benthamiana, and Gossypium raimondii [22].

The genomic signature of WGD is characterized by duplicated chromosomal segments distributed throughout the genome. These segmental duplications often form identifiable syntenic blocks that can be traced through comparative genomics. Following WGD, most duplicated genes are rapidly lost, with retention rates showing significant functional biases [20]. Genes involved in transcriptional regulation, signal transduction, and multiprotein complexes demonstrate higher retention probabilities, likely due to dosage balance constraints [20].

Tandem Duplication (TD)

In contrast to WGD, tandem duplication events affect localized genomic regions, producing clusters of paralogous genes in close physical proximity. This mechanism operates at a much finer genomic scale but occurs with greater frequency than WGD. In Arabidopsis, approximately 14% of all duplicates are arranged in tandem arrays [21]. Each TD event typically affects a small number of genes, but cumulative effects over evolutionary time can substantially expand specific gene families.

The genomic signature of TD is characterized by clustered gene arrangements with high sequence similarity located within confined genomic regions. These tandem arrays are particularly prevalent in plant genomes, with studies of 205 Archaeplastida genomes revealing evidence of convergent adaptation through TD across different lineages of root plants [23]. TDs exhibit a strong functional bias, frequently expanding genes involved in environmental interactions and stress responses [21] [23].

Table 1: Characteristics of Whole-Genome and Tandem Duplication Mechanisms

| Feature | Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD) | Tandem Duplication (TD) |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic scale | Entire genome | Localized genomic regions |

| Frequency | Rare, episodic (~1-100 MY) | Frequent, continuous |

| Number of genes affected | All genes in genome (~20,000-50,000) | Few to dozens of genes |

| Genomic organization | Dispersed syntenic blocks | Clustered arrays |

| Key identifying features | Synteny, synonymous substitution (Ks) peaks | Gene clusters, physical proximity |

| Prevalence in plants | 100% of angiosperms have evidence of ancient WGD | ~14% of Arabidopsis genes in tandem arrays |

Quantitative Impact on Gene Repertoire Size

Comparative Analysis of Duplication Mechanisms

The relative contributions of WGD and TD to repertoire expansion vary across plant lineages and gene families. Analysis of Populus trichocarpa revealed striking differences in the properties of genes retained following different duplication mechanisms. Genes derived from WGD are 700 bp longer on average and expressed in 20% more tissues compared to tandem duplicates [24]. This pattern suggests that WGD-derived genes may be subject to different selective constraints than TD-derived genes.

The functional composition of duplicated genes also differs markedly between mechanisms. Certain functional categories are consistently over-represented in each duplication class. Specifically, disease resistance genes and receptor-like kinases commonly occur in tandem but are significantly under-retained following WGD [24]. Conversely, WGD-derived duplicate pairs are enriched for members of signal transduction cascades and transcription factors [24]. This fundamental division in functional retention highlights how duplication mechanisms collectively shape genome content by expanding complementary functional categories.

Lineage-Specific Variations in NBS Gene Repertoires

The impact of duplication mechanisms on repertoire size is particularly evident in NBS-LRR gene families, which are crucial for plant immunity. Genomic analyses across diverse species reveal tremendous variation in NBS-LRR family sizes, from approximately 50 in papaya and cucumber to over 1,000 in Aegilops tauschii [25]. This variation reflects lineage-specific evolutionary trajectories driven by differential duplication and retention.

Research on Rosaceae species demonstrates distinct evolutionary patterns for NBS-LRR genes, including "first expansion and then contraction" in Rubus occidentalis and Potentilla micrantha, "continuous expansion" in Rosa chinensis, and "early sharp expanding to abrupt shrinking" in Prunus and Maleae species [6]. These patterns result from independent gene duplication and loss events following species divergence, with WGD and TD playing complementary roles in shaping these trajectories.

Table 2: Evolutionary Patterns of NBS-LRR Genes Across Plant Families

| Plant Family | Species | NBS-LRR Count | Evolutionary Pattern | Primary Duplication Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosaceae | Rosa chinensis | 2188 total across 12 species | Continuous expansion | WGD and TD |

| Rosaceae | Prunus species | 2188 total across 12 species | Early expansion then sharp contraction | WGD and TD |

| Poaceae | Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | 96 | Tandem clusters | Predominantly TD |

| Solanaceae | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Not specified | Expansion followed by contraction | WGD and TD |

| Fabaceae | Soybean (Glycine max) | ~500 | Consistent expansion | WGD and TD |

| Orchidaceae | Dendrobium catenatum | 115 | Not specified | Not specified |

| Orchidaceae | Gastrodia elata | 5 | Not specified | Not specified |

Functional and Evolutionary Consequences

Divergent Functional Retention Patterns

The mechanism of duplication profoundly influences the functional fate of retained genes. Genomic convergence analyses across Archaeplastida reveal that TD-derived genes are enriched in enzymatic catalysis and biotic stress responses [23]. This pattern is particularly pronounced in root plants, where TD frequency correlates with environmental factors, especially those related to soil microbial pressures [23]. Conversely, plants that transitioned to aquatic, parasitic, halophytic, or carnivorous lifestyles—reducing interaction with soil microbes—exhibit a consistent decline in TD frequency [23].

Whole-genome duplicates show contrasting functional biases, with preferential retention of genes involved in nucleic acid binding, transcription factor activity, and signal transduction [21] [26]. This division reflects fundamental differences in how natural selection acts on duplicates from different origins. Tandem duplicates appear to drive adaptation to rapidly changing environmental challenges, while whole-genome duplicates are more likely to retain fundamental regulatory functions constrained by dosage sensitivity.

Evolutionary Dynamics and Gene Fate

Following duplication, genes may undergo several possible evolutionary fates: non-functionalization (loss), neofunctionalization (acquiring new functions), or subfunctionalization (partitioning ancestral functions). The duplication mechanism influences which fate predominates. For WGD-derived duplicates, nearly half exhibit expression patterns consistent with random degeneration, while the remainder show more conserved expression than expected by chance, supporting a role for selection under gene balance constraints [24].

Tandem duplicates experience distinct evolutionary pressures, often including asymmetric expansion across lineages [21]. This pattern suggests that tandem genes undergo lineage-specific selection, potentially driving adaptive divergence. Additionally, tandem arrays provide substrates for ectopic recombination, facilitating the emergence of novel alleles through gene conversion and unequal crossing over [25]. These mechanisms generate diversity in plant immune receptors, enabling rapid co-evolution with pathogens.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Duplication Events

Genomic Identification of Duplication Events

Detailed Methodologies for Duplication Analysis

Whole-Genome Duplication Detection

Syntery Analysis: Identification of WGD events begins with the detection of syntenic blocks across the genome using tools like MCScanX or SynMap [22]. These blocks represent homologous chromosomal regions derived from ancestral duplication events. The methodology involves:

- Whole-genome alignment to identify homologous regions

- Collinearity assessment to verify preserved gene order

- Statistical validation to distinguish true synteny from background similarity

Ks Distribution Analysis: The age of duplication events can be estimated by calculating the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) between paralogous gene pairs [22]. This approach involves:

- Pairwise alignment of coding sequences from paralogs

- Ks calculation using models of codon substitution (e.g., Yang-Nielsen method)

- Peak identification in Ks distributions indicating episodic duplication

Phylogenetic Reconciliation: Gene family trees are reconstructed and reconciled with species trees to identify duplication events [22] [6]. The protocol includes:

- Multiple sequence alignment of gene family members

- Gene tree construction using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods

- Reconciliation analysis to map duplication events to specific phylogenetic branches

Tandem Duplication Detection

Gene Cluster Identification: Tandemly duplicated genes are identified as paralogs located in close physical proximity on chromosomes [25] [6]. The standard criteria include:

- Physical proximity (typically ≤ 10 genes apart)

- Sequence similarity (BLAST e-value ≤ 1e-10)

- Functional relatedness (similar domain architecture)

Orthogroup Analysis: Genes are clustered into orthologous groups across multiple species using tools like OrthoFinder [10]. Lineage-specific expansions indicate potential tandem duplication events. The methodology involves:

- All-vs-all BLAST of proteomes from multiple species

- Orthogroup clustering using MCL algorithm

- Expansion detection through comparison of gene counts across lineages

Expression and Functional Validation

Expression Divergence Analysis: Microarray or RNA-seq data are used to assess expression pattern evolution between duplicates [24]. The protocol includes:

- Expression profiling across multiple tissues and conditions

- Correlation analysis between duplicate pairs

- Divergence classification into conservation, specialization, or degeneration

Functional Characterization: Experimental validation of duplicate gene functions involves both computational and laboratory approaches:

- Domain architecture analysis using Pfam and CDD

- Subcellular localization prediction or validation

- Mutant analysis using gene silencing (e.g., VIGS) or knockout lines

- Interaction studies using yeast-two-hybrid or co-immunoprecipitation

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Gene Duplication

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Genomic DNA | Reference genome assembly and duplication detection | Identifying syntenic blocks and tandem arrays [10] |

| RNA-seq Data | Expression divergence analysis between duplicates | Assessing subfunctionalization after duplication [24] |

| OrthoFinder Software | Orthogroup inference across species | Identifying lineage-specific expansions [10] |

| Pfam/CDD Databases | Protein domain annotation | Classifying NBS-LRR genes into TNL, CNL, RNL subclasses [6] |

| VIGS (Virus-Induced Gene Silencing) | Functional validation of duplicate genes | Testing role of specific NBS genes in disease resistance [10] |

| MicroRNA Target Prediction Tools | Regulatory network analysis | Identifying post-transcriptional regulation of NBS-LRR genes [11] |

Whole-genome and tandem duplication events have distinct but complementary impacts on gene repertoire size in plants. WGD provides the evolutionary substrate for large-scale genomic reorganization and the retention of dosage-sensitive regulatory genes, while TD drives the rapid expansion of environmentally responsive gene families, particularly those involved in biotic stress responses like NBS domain genes. The interplay between these mechanisms creates a dynamic genomic landscape where repertoire size reflects both deep evolutionary history and recent adaptive pressures. Understanding these processes illuminates the evolutionary forces that shape plant genomes and provides insights for engineering disease resistance in crop species through manipulation of duplication-derived gene families. Future research integrating pan-genomic approaches with functional studies will further elucidate how duplication mechanisms collectively contribute to plant diversification and adaptation.

Chromosomal Distribution and the Formation of Resistance Gene Clusters

Within the plant immune system, nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes constitute one of the largest and most critical gene families for disease resistance. The proteins encoded by these genes recognize diverse pathogen effectors and initiate robust defense responses, often culminating in a hypersensitive reaction to restrict pathogen spread [8] [19]. A hallmark of these genes is their non-random genomic distribution; they are frequently organized into complex clusters within plant chromosomes [27] [28] [29]. This clustered arrangement is not merely structural but is fundamentally linked to the evolutionary dynamics that enable plants to keep pace with rapidly evolving pathogens. The genomic organization and evolution of these resistance (R) gene clusters are therefore central to understanding plant-pathogen interactions and for developing sustainable disease resistance strategies in crops. This guide examines the patterns and processes governing the chromosomal distribution and formation of R-gene clusters, providing a framework for their study within the broader context of NBS domain gene diversification.

Chromosomal Distribution Patterns of R-Genes

Preferential Localization in Telomeric Regions

Resistance genes are non-randomly distributed across plant chromosomes, showing a strong preference for telomeric regions. A study in hexaploid wheat analyzing Fusarium-responsive gene clusters (FRGCs) found that 56% were located in the distal telomeric zones of chromosome arms, while 44% were in interstitial regions, and none were found in centromeric regions [30]. This distribution correlates with the overall higher gene density in telomeric regions, but also highlights that R-genes are enriched in genomic areas known for higher recombination rates [30].

Subgenome Bias in Allopolyploids

In allopolyploid species, R-genes often show an uneven distribution between subgenomes. In wheat, the D subgenome contains significantly more Fusarium-responsive genes (10.7% of its total genes) compared to the A (9.7%) and B (9.3%) subgenomes [30]. Similarly, the D subgenome harbors 50% of the identified Fusarium-responsive gene clusters, despite the three subgenomes having roughly similar total gene numbers [30]. This suggests selective pressure has shaped R-gene content differently across subgenomes following polyploidization.

Cluster Size and Gene Density

R-gene clusters can vary substantially in physical size and gene content. In wheat, FRGCs range from 18 to 1268 kb in physical size and contain between 5 and 11 responsive genes [30]. The average distance between genes within these clusters (58 kb) is significantly smaller than the genomic average (132 kb), indicating high gene density within these specialized genomic regions [30].

Table 1: Chromosomal Distribution of Resistance Gene Clusters in Selected Plant Species

| Species | Cluster Location | Subgenome Bias | Cluster Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | 56% Telomeric, 44% Interstitial, 0% Centromeric | D subgenome enrichment (50% of FRGCs) | 5-11 genes per cluster; 18-1268 kb size | [30] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Terminal end of chromosome 11L | Higher in indica (Kasalath) than japonica (Nipponbare) | 1.2-1.9 Mb region; Up to 53 NBS-LRR genes in Kasalath | [27] |

| Coffee (Coffea arabica) | Distal position on homeologous group 1 | - | 800 kb SH3 locus; 3-5 CNL genes per haplotype | [29] |

| Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) | - | - | 156 NBS-LRR genes identified genome-wide | [8] |

Evolutionary Mechanisms Driving Cluster Formation

The Birth-and-Death Evolution Model

R-gene clusters primarily evolve through a birth-and-death process, where new resistance specificities are generated by gene duplication, followed by functional diversification, while some copies are silenced or lost from the genome [28] [29]. This model is supported by phylogenetic analyses showing that orthologous R-genes between species are more similar than paralogous genes within the same cluster, indicating a low rate of sequence homogenization through unequal crossing-over [28]. Rather than concerted evolution, the birth-and-death model emphasizes divergent selection acting on arrays of solvent-exposed residues in the LRR domain, driving the evolution of individual R genes within a haplotype [28].

Role of Gene Duplication Events

Various duplication mechanisms contribute to the expansion of R-gene clusters:

- Tandem Duplication: This is a primary mechanism for local cluster expansion. In rice, cultivated varieties possess more NBS-LRR genes in specific chromosomal regions compared to their wild ancestors, indicating selection for increased copy number during domestication [27].

- Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD): Allopolyploidization events contribute significantly to R-gene repertoire expansion. In Nicotiana tabacum, an allotetraploid, 76.62% of NBS genes could be traced back to their parental genomes (N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis), demonstrating the impact of WGD [31].

- Segmental Duplication: Large chromosomal duplications can transfer entire R-gene clusters to new genomic locations, creating additional complexity in the R-gene landscape.

Table 2: Evolutionary Mechanisms in Resistance Gene Cluster Formation

| Mechanism | Molecular Process | Impact on Cluster Formation | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth-and-Death Evolution | Gene duplication followed by divergent selection and gene loss | Generates new resistance specificities while maintaining diversity | Phylogenetic analysis showing orthologs > paralogs similarity [28] |

| Tandem Duplication | Local duplication of genes in close proximity | Expands gene numbers within existing clusters | Increased NBS-LRRs in cultivated vs. wild rice [27] |

| Whole-Genome Duplication | Duplication of entire genomes | Provides raw genetic material for neofunctionalization | NBS gene inheritance in allopolyploid tobacco [31] |

| Gene Conversion | Non-reciprocal transfer of sequence information | Homogenizes sequences or creates new chimeric genes | Sequence exchange between paralogs in coffee SH3 locus [29] |

| Positive Selection | Diversifying selection on specific residues | Drives amino acid variation in ligand-binding sites | Elevated Ka/Ks ratios in LRR solvent-exposed residues [29] |

Diversifying Selection on Specific Domains

Different domains of NBS-LRR proteins experience distinct selective pressures. The LRR domain, particularly codons encoding solvent-exposed residues, shows significantly elevated ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks > 1), indicating positive selection for amino acid diversification [28] [29]. This diversifying selection likely enables recognition of evolving pathogen effectors. In contrast, the NBS domain, crucial for nucleotide binding and signal transduction, is predominantly under purifying selection (Ka/Ks < 1) to maintain its core signaling function [29].

Ectopic Recombination and Gene Conversion

Gene conversion events between paralogous genes within clusters and even between homoeologous clusters in allopolyploids contribute to R-gene evolution. In coffee, gene conversion has been detected between paralogs in all three analyzed genomes and between the two subgenomes of C. arabica [29]. This process can create new resistance specificities by generating chimeric genes or can homogenize sequences, maintaining functional conservation.

Evolutionary Workflow of R-Gene Clusters

Functional Significance of Clustered Arrangement

Facilitated Co-Adaptation of Signaling Components

The clustered arrangement of R-genes enables the coordinated evolution and functional interaction of resistance proteins. Research on the potato Rx CC-NBS-LRR protein demonstrated that separate protein domains (CC-NBS and LRR) can physically interact and function in trans to confer a hypersensitive response upon pathogen recognition [19]. This domain complementation suggests that clustering facilitates the co-adaptation of signaling components that must physically interact for proper immune function.

Synergistic Functionality in Disease Resistance

Gene clusters can encode proteins that function synergistically to provide resistance. The rice Pikm locus requires two adjacent NBS-LRR genes (Pikm1-TS and Pikm2-TS) working in combination to confer complete blast resistance [27]. This paired-gene resistance mechanism demonstrates how clustering maintains genetic linkages between co-adapted genes that function together in plant immunity.

Variation Reservoir for Pathogen Recognition

R-gene clusters serve as reservoirs of genetic variation from which new pathogen recognition specificities can evolve. The hypervariability of solvent-exposed residues in the LRR domains, maintained through diversifying selection, enables a broad recognition capacity against diverse pathogens [28] [29]. The clustered arrangement facilitates the generation of new specificities through recombination and gene conversion between paralogous sequences [28].

Research Methodologies for Studying R-Gene Clusters

Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization

Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Searches: Using profile HMMs of conserved domains (e.g., NB-ARC: PF00931 from Pfam) to identify candidate NBS-LRR genes [8] [31]. Command-line tools like HMMER are used with expectation value cutoffs (E-values < 1*10â»Â²â°) [8].

Domain Architecture Analysis: Confirming identified candidates using multiple domain databases (Pfam, SMART, NCBI CDD) to classify genes into structural subfamilies (TNL, CNL, RNL, TN, CN, N) [8] [31].

Manual Curation: Removing duplicates and verifying domain completeness through manual inspection to generate high-confidence gene sets [8].

Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Analysis

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Using tools like Clustal W or MUSCLE with default parameters to align protein sequences [8] [31].

Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Implementing maximum likelihood methods in MEGA or FastTreeMP with bootstrap testing (1000 replicates) to infer evolutionary relationships [8] [31].

Selection Pressure Analysis: Calculating non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates using KaKs_Calculator to detect positive or purifying selection [31].

Genomic Distribution and Cluster Analysis

Physical Mapping: Constructing BAC-based chromosomal physical maps and complete sequencing of target regions to uncover structural variations [27].

Sliding Window Analysis: Scanning chromosomes with a sliding window (e.g., 10 genes) to calculate gene density and consecutiveness, compared to random permutations to identify significant clustering [30].

Synteny Analysis: Using MCScanX with reciprocal BLASTP searches to identify syntenic blocks and homologous clusters across genomes [31].

R-Gene Cluster Research Workflow

Experimental Validation Approaches

Expression Analysis: RNA-seq differential expression analysis to identify pathogen-responsive genes within clusters. Typical parameters include fold-change ≥ 1.5 and false discovery rate < 0.05 [31] [30].

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS): Transient silencing of candidate genes in resistant plants to validate function, as demonstrated in cotton where silencing of GaNBS reduced virus resistance [10].

Protein Interaction Studies: Co-immunoprecipitation and yeast two-hybrid assays to investigate physical interactions between R-protein domains and with pathogen effectors [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Sources/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| HMM Profile (PF00931) | Identification of NBS domain-containing genes | Pfam Database [8] |

| Domain Databases | Verification of domain architecture and classification | SMART, NCBI CDD, Pfam [8] [31] |

| BAC Libraries | Physical mapping and sequencing of cluster regions | Species-specific genomic libraries [27] |

| Multiple Alignment Tools | Phylogenetic analysis and evolutionary relationships | Clustal W, MUSCLE [8] [31] |

| Synteny Analysis Software | Detection of homologous regions and evolutionary history | MCScanX, BLASTP [31] |

| RNA-seq Datasets | Expression profiling under pathogen stress | Public repositories (NCBI SRA) [31] [30] |

| VIGS Vectors | Functional validation through transient gene silencing | TRV-based vectors for Solanaceae [10] |

The chromosomal distribution of R-genes into clustered arrangements represents a fundamental genomic strategy for plant immunity. Their preferential localization in recombination-active telomeric regions, coupled with evolutionary mechanisms like birth-and-death evolution, tandem duplication, and diversifying selection, enables the rapid generation of novel recognition specificities. The functional significance of this organization extends beyond mere physical proximity to encompass coordinated expression, functional interaction, and synergistic activity against pathogens. Research methodologies spanning bioinformatic identification, evolutionary analysis, and experimental validation continue to reveal the complex dynamics of these critical genomic regions. Understanding the principles governing R-gene cluster formation and maintenance provides not only fundamental insights into plant-pathogen co-evolution but also practical strategies for engineering durable disease resistance in crop plants.

Advanced Pipelines for Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Characterization of NBS Genes

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for investigating the diversification of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) domain genes in plants. We present integrated bioinformatic workflows combining HMMER-based domain identification using the PF00931 model and OrthoFinder phylogenetic orthology inference to elucidate evolutionary patterns, gene family expansion mechanisms, and functional diversification in plant immunity genes. The methodologies outlined enable systematic analysis of NBS gene families across multiple plant species, facilitating insights into tandem duplication events, whole-genome triplication impacts, and species-specific evolutionary trajectories. This pipeline has been successfully applied to species including apple, cassava, Brassica, and tomato, demonstrating its utility for comparative genomic studies of plant disease resistance mechanisms.

NBS domain genes constitute one of the largest and most critical gene families in plant immune systems, encoding intracellular receptors that recognize pathogen effectors and activate defense responses [32] [11]. These genes typically contain a nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain and frequently C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRRs), forming the NBS-LRR gene family that represents the predominant class of plant resistance (R) genes [33] [34]. The NBS domain, approximately 300 amino acids in length, functions as a molecular switch that binds and hydrolyzes ATP/GTP during plant defense signaling [32] [11]. Based on N-terminal domain architecture, NBS-LRR genes are classified into two major subfamilies: TNLs, containing Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domains, and CNLs, containing coiled-coil (CC) domains [32] [33].

Plant NBS gene families exhibit remarkable diversity in size, organization, and evolutionary patterns across species [10] [11]. Genomic studies have identified 1,015 NBS-LRRs in apple, 228 in cassava, 245 in wild tomato, 157 in Brassica oleracea, and 206 in Brassica rapa [32] [33] [34]. This diversity arises from various duplication mechanisms including tandem duplication, segmental duplication, and whole-genome multiplication events [32] [10]. The bioinformatic workflows presented in this guide provide standardized approaches for identifying, classifying, and comparing these important immune receptors across plant species, enabling researchers to decipher the evolutionary mechanisms driving NBS gene diversification in plants.

HMMER-Based Identification of NBS Domain Genes

Protocol for Domain Identification Using PF00931

The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile for the NBS domain (PF00931) provides the foundation for comprehensive identification of NBS-encoding genes from plant proteomes. The following protocol outlines the standard workflow:

Table 1: Key Tools and Resources for HMMER-based NBS Gene Identification

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER3 Suite | Hidden Markov Model searches | Identification of candidate NBS domains with e-value < 1e-04 [32] [35] |

| Pfam Database | Protein family database | Source of PF00931 (NBS/ NB-ARC) HMM profile [32] [34] |