Genomic BLUP and Relationship Matrices: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the implementation of Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP) and genomic relationship matrices (G-matrices) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Genomic BLUP and Relationship Matrices: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the implementation of Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP) and genomic relationship matrices (G-matrices) for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts, from the limitations of pedigree-based models to the advantages of marker-based genomic relationships. The guide details practical methodological considerations for G-matrix construction and implementation, including single-step approaches for integrating genotyped and non-genotyped individuals. It further explores advanced optimization strategies, such as weighted matrices and feature selection, to enhance prediction accuracy for complex traits. Finally, the article presents a comparative analysis of GBLUP performance against alternative methods like machine learning, validating its application across diverse species and genetic architectures to inform its potential in human biomedical research and clinical applications.

From Pedigree to Genomics: The Foundational Shift in Genetic Prediction

Limitations of Pedigree-Based Relationship Matrices (A-Matrix) and Shallow Pedigrees

In genetic evaluation and selective breeding, accurately quantifying the genetic relationships between individuals is fundamental for estimating heritability, predicting breeding values, and managing genetic diversity. For decades, the pedigree-based relationship matrix (A-matrix), which calculates the expected proportion of the genome shared between individuals based on known ancestry, has been the cornerstone of these analyses [1]. However, the A-matrix relies on critical assumptions: pedigrees are complete and accurate over many generations, and genes are transmitted from parents to offspring following Mendelian sampling without selection. In practice, these conditions are often violated, especially in species with shallow pedigrees or where tracking parentage is biologically or logistically challenging, such as in forest trees and some livestock populations [2] [1].

These limitations necessitate a shift towards marker-based genomic relationship matrices (G-matrices), which use genome-wide molecular markers to measure the actual proportion of alleles shared between individuals, thereby capturing realized genetic similarities [3] [1]. This application note details the specific drawbacks of the A-matrix, provides experimental evidence of its inadequacies, and outlines protocols for implementing more robust genomic evaluation methods, contextualized within broader research on Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (G-BLUP).

Key Limitations of the A-Matrix and Shallow Pedigrees

The use of the A-matrix in populations with shallow or incomplete pedigrees introduces significant biases and inaccuracies in genetic parameter estimates. The table below summarizes the core limitations and their consequences.

Table 1: Core Limitations of Pedigree-Based Relationship Matrices (A-Matrix) in Shallow Pedigrees

| Limitation | Description | Impact on Genetic Estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Hidden Relatedness [2] [1] | Undetected familial relationships (e.g., full-sibs, selfing) due to incomplete pedigree tracking (e.g., in open-pollinated designs). | Overestimation of additive genetic variance; breeding values are shrunk toward the population mean, reducing accuracy and leading to inaccurate selection [2]. |

| Ignored Mendelian Sampling [1] | The A-matrix treats all family members (e.g., half-sibs) as having identical relatedness, ignoring variation from the random segregation of alleles. | Inflated breeding values; fails to capture true genetic differences between siblings, lowering prediction accuracy [1]. |

| Incompatibility with Genomic Data [4] | The scale and level of the A-matrix often do not align with the G-matrix, as pedigrees cannot account for changes in allele frequency due to selection or drift. | Biased genomic predictions in single-step evaluations; requires statistical rescaling to harmonize matrices, adding complexity [2] [4]. |

| Inability to Capture Inbreeding [5] | Pedigree-based inbreeding coefficients ((F_{PED})) underestimate actual autozygosity, especially with limited ancestral depth. | Underestimation of realized inbreeding and its detrimental effects (inbreeding depression), risking the long-term health of managed populations [5]. |

| No Resolution of Non-Additive Effects [1] | The A-matrix is typically used to estimate only additive genetic variance, confounding it with non-additive effects (dominance, epistasis). | Overestimation of narrow-sense heritability; inability to decompose genetic variance, limiting understanding of trait architecture [1]. |

Quantitative Evidence: A-Matrix vs. G-Matrix

Empirical studies across multiple species directly demonstrate the consequences of these limitations. The following table compiles key findings from the literature.

Table 2: Empirical Comparisons of Pedigree-Based (A-Matrix) and Genomic (G-Matrix) Evaluations

| Species (Trait) | Pedigree-Based Estimate (A-Matrix) | Genomic Estimate (G-Matrix) | Outcome and Improvement with G-Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|

| White Spruce (Wood Density) [1] | Additive variance confounded with non-additive variances. | Realistic additive variance; dominance and epistatic variances estimated. | Heritability estimates more realistic; non-additive variances quantified for the first time in an open-pollinated test. |

| Eucalyptus nitens (Stem Diameter) [2] | Accumulated unrecognized relatedness shrunk breeding values. | Sib-ship reconstruction resolved hidden relatedness. | Increased prediction accuracy; profound impact on traits with inbreeding depression. |

| Slovenian Lipizzan Horse (Inbreeding) [5] | Pedigree-based inbreeding ((F_{PED})) underestimated autozygosity. | Genomic estimators ((F{ROH}), (F{HBD})) revealed higher inbreeding, often from distant ancestors. | Genomic tools provided a fuller picture of inbreeding, enabling better conservation management. |

| Commercial Pigs & Bulls (Production Traits) [3] | Lower theoretical accuracy of breeding values. | GBLUP with optimized G-matrix (e.g., GD for pigs). | Superior prediction accuracy for various traits; method efficacy is species- and trait-dependent. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Hidden Relatedness and Inbreeding Depression in a Eucalyptus OP Population

This protocol is adapted from Klápště et al. (2018) [2].

Objective: To evaluate the impact of hidden relatedness on genetic parameters and breeding values in an advanced-generation open-pollinated (OP) breeding population, and to implement a single-step genetic evaluation using a sib-ship reconstructed relationship matrix.

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant Material: 3,593 individuals from a third-generation Eucalyptus nitens population, structured into 116 documented half-sib families.

- Phenotypic Data: Measurements for diameter at breast height (DBH), straightness (STR), and malformation (MAL).

- Genotyping: EUChip60K SNP chip. Filter SNPs for GenTrain score > 0.5, GenCall > 0.15, minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05, and SNP call rate > 0.6, resulting in 13,844 high-quality SNPs for analysis.

Software: Statistical software capable of mixed linear models and genomic evaluation (e.g., ASReml-R).

Methodology:

- Sib-ship Reconstruction: Use the high-quality SNP set and a likelihood-based approach to infer the true familial relationships (full-sibs, half-sibs, selfs) among the 691 genotyped individuals, correcting the documented pedigree.

- Relationship Matrix Construction:

- Scenario A (Documented Pedigree): Construct the traditional pedigree-based relationship matrix (A).

- Scenario B (Sib-ship Reconstruction): Construct a more accurate relationship matrix based on the sib-ship reconstruction.

- Single-Step Genetic Evaluation:

- Implement a single-step model that integrates both pedigree and genomic information into a combined relationship matrix (H).

- Use the relationship matrix from Step 2 to rescale the marker-based relationship matrix (G).

- Fit the following linear mixed model for each trait:

y = Xβ + Za + Zr + Zr(s) + ewhereyis the vector of phenotypes,βis the vector of fixed effects (e.g., seed orchard),ais the vector of random animal effects ~ (N(0, H\sigma^2_a)),ris the replication effect,r(s)is the set effect, andeis the residual.

- Analysis: Compare the two scenarios for model fit, theoretical accuracy of breeding values, and estimated heritability, particularly for DBH, a trait known to be affected by inbreeding depression.

Protocol 2: Genetic Variance Decomposition in White Spruce OP Families

This protocol is based on the study by Beaulieu et al. (2016) [1].

Objective: To decompose the total genetic variance into additive and non-additive components using a genomic model, overcoming the limitations of the A-matrix in an OP family test.

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant Material: 1,694 individuals from 214 white spruce OP families grown in a randomized complete block design with six blocks.

- Phenotypic Data: 30-year wood density measurements from increment cores.

- Genotyping: Illumina Infinium HD iSelect bead chip (PgAS1) with 7,338 SNP loci. Apply standard quality control (MAF, call rate).

- Software: Software capable of REML estimation using a genomic relationship matrix (e.g., GCTA, ASReml).

Methodology:

- Relationship Matrix Construction:

- Pedigree-based A-matrix: Constructed assuming all OP families are independent half-sib families.

- Genomic G-matrix: Construct the additive genomic relationship matrix ( G{add} ) using the VanRaden (2008) Method 1 [1]: ( G{add} = \frac{ZZ'}{2\sum pi(1-pi)} ) where ( Z ) is the matrix of genotypes coded as 0, 1, 2 adjusted by allele frequencies ( p_i ).

- Statistical Modeling:

- Fit separate models using the A-matrix and the G-matrix.

- The basic model is:

y = Xβ + Za + e - For the pedigree model,

a~ (N(0, A\sigma^2_a)). - For the genomic model,

a~ (N(0, G{add}\sigma^2a)). The genomic model implicitly accounts for Mendelian sampling and hidden relatedness.

- Variance Component Estimation: Use Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) to estimate the additive genetic variance ((\sigma^2a)) and residual variance ((\sigma^2e)) for both models.

- Comparison: Calculate narrow-sense heritability as (h^2 = \sigma^2a / (\sigma^2a + \sigma^2e)) for both models. Compare the estimates. The model using ( G{add} ) is expected to provide a less inflated and more realistic estimate of heritability by accounting for hidden non-additive genetic structures.

- Relationship Matrix Construction:

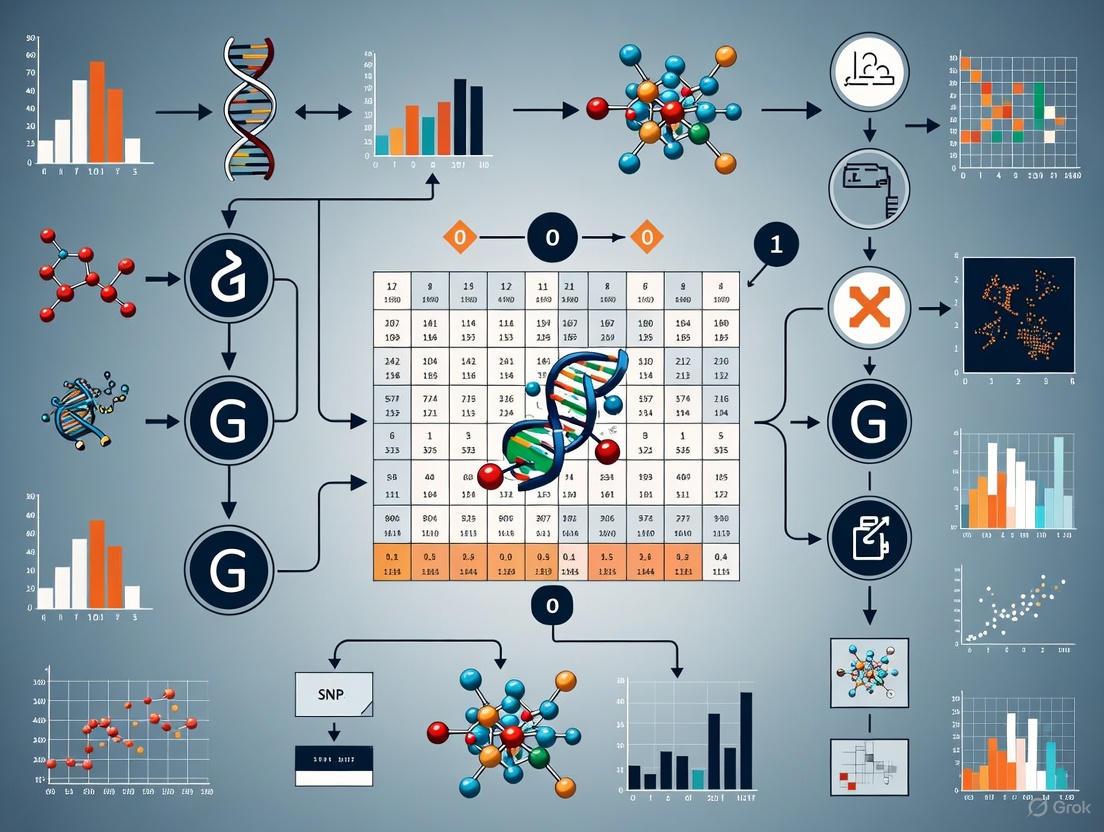

Workflow Visualization: From Pedigree to Genomic Evaluation

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual and practical shift from traditional pedigree-based evaluation to a more accurate genomic framework, highlighting key steps and outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Implementing Genomic Evaluations

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density SNP Array | Genome-wide genotyping to determine individual genetic makeup for constructing the G-matrix. | Illumina Infinium SNP chips (e.g., PorcineSNP60, Equine 70K, PgAS1 for white spruce) [3] [1] [5]. |

| Genomic Relationship Matrix (G) Methods | Formulas to calculate the realized genetic similarity between individuals from marker data. | VanRaden Method 1 [1], various scaling methods (G05, GOF, GN, GD) - choice is species-dependent [3]. |

| Sib-ship Reconstruction Software | To infer correct familial relationships from genotype data and correct pedigree errors. | Used in Eucalyptus study to resolve hidden relatedness [2]. |

| Single-Step Evaluation Software | Software that can integrate A and G matrices into a single H matrix for unified genetic evaluation. | Essential for combining historical pedigree data with new genomic information [2] [6] [4]. |

| PLINK / R (AGHmatrix, BGLR) | Open-source software for extensive genomic data quality control, analysis, and relationship matrix computation. | PLINK used for ROH analysis [5]; R packages for statistical genetics and genomic prediction [3] [5]. |

| Ethyl 3-Methyl-2-butenoate-d6 | Ethyl 3-Methyl-2-butenoate-d6, CAS:53439-15-9, MF:C7H12O2, MW:134.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Diethyl propylmalonate | Diethyl Propylmalonate|2163-48-6|CAS 2163-48-6 | Diethyl propylmalonate (CAS 2163-48-6), a high-purity malonic acid derivative for organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The limitations of the pedigree-based A-matrix in the presence of shallow pedigrees are severe and well-documented, leading to biased estimates that can compromise the effectiveness of breeding programs and conservation efforts. The empirical evidence and protocols outlined herein demonstrate that transitioning to marker-based genomic relationship matrices (G-matrices) is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental necessity for accurate genetic evaluation. The implementation of single-step methods and genomic models allows researchers to overcome the issues of hidden relatedness, Mendelian sampling, and inflated variance estimates, paving the way for more precise and accelerated genetic gain. Future research should focus on optimizing G-matrix construction methods for specific population structures and further integrating these approaches into routine genetic evaluation workflows.

The Genomic Relationship Matrix (G-matrix) is a foundational component in modern genomic selection, enabling the estimation of breeding values using genome-wide molecular markers. By quantifying the genetic similarity between individuals based on their single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiles, the G-matrix has revolutionized the field of genetic evaluation. This cornerstone technology allows breeders and researchers to make more accurate selections early in an organism's life, significantly accelerating genetic progress in plant and animal breeding programs. The implementation of the G-matrix within Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (G-BLUP) models has become a standard approach in genomic prediction, offering substantial advantages over traditional pedigree-based methods by more precisely capturing the genetic relationships and Mendelian sampling variation among individuals [3].

Principles of the G-Matrix

Fundamental Mathematical Construction

The G-matrix is constructed from molecular marker data, typically SNPs, which are coded numerically to represent individual genotypes. The basic formulation begins with a genotype matrix M, of dimensions n × m (where n is the number of individuals and m is the number of markers), containing values of 0, 1, or 2 representing the count of alternative alleles for each SNP. An initial, unscaled relationship matrix can be simply derived as MM′, which counts the number of alleles shared between individuals [3].

To make this matrix comparable to the traditional numerator relationship matrix (A) from pedigree records, the M matrix is typically centered and scaled. The centered genotype matrix is calculated as Z = M - P, where P is a matrix containing 2páµ¢ for each column i, and páµ¢ is the frequency of the second allele at locus i. The final scaled G-matrix is then computed as [3]:

G = ZZ′ / {2∑[pᵢ(1-pᵢ)]}

This scaling ensures that the elements of G are approximately on the same scale as the elements of the pedigree-based relationship matrix A, with average diagonal elements close to 1 [3].

Allele Frequency Considerations

The choice of allele frequencies used in centering the genotype matrix significantly impacts the properties of the resulting G-matrix. In an ideal scenario, allele frequencies from the unselected base population would be used, but these are rarely available in practice. Researchers have proposed several alternative approaches [3]:

- G05: Uses 0.5 for all markers, equivalent to assuming equal allele frequencies across all loci

- GOF: Uses the observed allele frequencies from the genotyped individuals

- GMF: Uses the average minor allele frequency across all markers

- GN: Applies normalization to ensure the average diagonal element is 1

- GD: Weights markers by the reciprocals of their expected variance, giving more weight to rare alleles

These different approaches accommodate various breeding scenarios and population structures, with the optimal choice depending on the specific application and available data.

Figure 1: Workflow for constructing a genomic relationship matrix, showing key steps from raw genotype data to the final G-matrix ready for analysis. The process involves quality control, genotype coding, matrix centering and scaling, and selection of an appropriate construction method based on the breeding context and population structure.

Key Advantages of the G-Matrix

Enhanced Accuracy of Genetic Values

The G-matrix provides a more precise estimate of genetic relationships between individuals compared to pedigree-based relationships. While the pedigree-based A matrix estimates expected genetic similarity based on ancestry, the G matrix captures the actual proportion of the genome shared between individuals, accounting for Mendelian sampling variation. This leads to more accurate estimates of breeding values, particularly for traits with complex inheritance patterns [3].

In commercial pig breeding programs, the single-step GBLUP (ssGBLUP) approach, which integrates both genomic and pedigree data, has demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to traditional GBLUP and various Bayesian models. For carcass and body measurement traits, ssGBLUP achieved prediction accuracies ranging from 0.371 to 0.502, outperforming other methods across all traits studied [7].

Species-Specific Optimization

The G-matrix framework allows for species-specific optimization to maximize prediction accuracy. Research has shown that different G-matrix construction methods perform variably across species, with population structure being a key determining factor. For instance, the GD matrix, which weights markers by the reciprocals of their expected variance, demonstrated significant improvements in prediction accuracy for pig traits, while most scaled G-matrices showed minimal effects on mice, wheat, and bull data [3].

This species-specific performance highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate G-matrix construction method based on the breeding population. In bull populations with large reference sizes and high-density genetic markers, the choice of G-matrix construction method had minimal impact on prediction accuracy, suggesting that the influence of G-matrix construction diminishes in large-scale, high-density genomic datasets [3].

Accommodation of Complex Genetic Architectures

Advanced G-matrix formulations can account for varying genetic architectures across different traits. The standard GBLUP model assumes all markers contribute equally to genetic variation, which may not be biologically realistic for traits influenced by major genes. The GD matrix addresses this limitation by weighting markers differently based on their expected contribution to genetic variance [3].

Further innovations include the GWABLUP approach, which uses genome-wide association study (GWAS) results to differentially weight all SNPs in a weighted GBLUP analysis. This method has demonstrated reliability improvements of up to 10% for milk yield traits compared to standard GBLUP, effectively bridging the gap between GWAS and genomic prediction [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Relationship Matrix Construction Methods

| Method | Allele Frequency Source | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G05 | Fixed at 0.5 for all markers | Simple, no need for frequency estimation | When base population is unknown; some allele frequencies unknown | Minimal effect in mice, wheat, bulls; species-dependent [3] |

| GOF | Observed frequencies in genotyped individuals | Most widely used method | General purpose applications | Widely applied but performance varies by population [3] |

| GMF | Average minor allele frequency | Gives more weight to rare alleles | When rare alleles are important | Similar to G05 but more emphasis on rare variants [3] |

| GN | Various, with normalization | Average diagonal elements close to 1 | When compatibility with pedigree matrix A is needed | Recommended for single-step BLUP for A-matrix compatibility [3] |

| GD | Various, with variance weighting | Weights markers by reciprocal of expected variance | Traits with major genes; human genetic diseases | Significant improvement for pig traits [3] |

| GWABLUP | GWAS-informed weighting | Uses posterior probabilities from GWAS as weights | Traits with known QTL regions; complex architectures | 10% more reliable than GBLUP for milk yield [8] |

G-Matrix Implementation Protocols

Basic GBLUP Implementation

The standard GBLUP model is implemented using the following mixed model equation:

y = Xb + Zg + e

Where:

- y is the vector of phenotypic observations

- X is the design matrix for fixed effects

- b is the vector of fixed effects

- Z is the design matrix for random animal effects

- g is the vector of random additive genetic effects ~N(0, Gσ²g)

- e is the vector of random residuals ~N(0, Iσ²e)

- G is the genomic relationship matrix

- σ²g is the genomic variance

- σ²e is the residual variance [7]

The mixed model equations are then solved to obtain estimates of the fixed effects and predicted genomic breeding values. Variance components (σ²g and σ²e) are typically estimated using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) methods [7].

Single-Step GBLUP (ssGBLUP) Protocol

The single-step approach seamlessly integrates genomic and pedigree information by combining the genomic relationship matrix for genotyped animals with the pedigree-based relationship matrix for non-genotyped animals. The key steps include:

Construct the H Matrix Inverse: The inverse of the combined relationship matrix Hâ»Â¹ is constructed as follows:

Hâ»Â¹ = Aâ»Â¹ + [ \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \ 0 & Gâ»Â¹ - Aâ‚‚â‚‚â»Â¹ \end{bmatrix} ]

Where Aâ»Â¹ is the inverse of the pedigree relationship matrix, Gâ»Â¹ is the inverse of the genomic relationship matrix, and Aâ‚‚â‚‚â»Â¹ is the inverse of the pedigree relationship matrix for genotyped animals [9].

Blending and Tuning: To ensure numerical stability and compatibility between G and Aâ‚‚â‚‚, blending and tuning are often applied:

- Blending: Gb = wG + (1-w)Aâ‚‚â‚‚, where w is typically 0.80-0.95

- Tuning: Adjusts G to have the same average diagonal and off-diagonal elements as Aâ‚‚â‚‚ [9]

Parameter Optimization: Optimal blending (β = 0.30-0.40), tuning (τ), and scaling (ω = 0.60-1.00) parameters should be determined through validation to maximize prediction accuracy for specific populations and traits [9].

Multi-Breed Genomic Evaluation

For numerically small breeds, multi-breed genomic evaluation using a shared G-matrix can significantly improve prediction accuracy. The protocol involves:

Assess Genetic Similarity: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and evaluate Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) decay patterns to identify genetically similar breeds that can be combined in a multi-breed reference population [10].

Construct Multi-Breed G-Matrix:

- Shared GRM Approach: Use a single genomic relationship matrix for all animals across breeds, assuming SNPs have identical effects

- Non-Shared GRM Approach: Model breed-specific SNP effects, accounting for breed-wise allele frequencies

- Metafounder Approach: Use pseudo-individuals to establish genetic relationships between base populations [10]

Validate Prediction Accuracy: Compare GEBV accuracies between single-breed and multi-breed approaches using validation populations [10].

Table 2: Impact of Multi-Breed Reference Populations on Genomic Prediction Accuracy in Cattle

| Breed Combination | Single-Breed Accuracy | Shared GRM Approach | Non-Shared GRM Approach | Metafounder Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gir (Single) | 0.65 | - | - | - |

| Sahiwal (Single) | 0.60 | - | - | - |

| Kankrej (Single) | 0.49 | - | - | - |

| Gir-Kankrej Multi-breed | - | 0.605 (+23.6%) | 0.611 (+24.6%) | 0.573 (+16.9%) |

| Gir-Sahiwal-Kankrej Multi-breed | - | 0.592 (+20.8%) | 0.598 (+22.0%) | 0.565 (+15.3%) |

Note: Percentage improvements for Kankrej breed shown in parentheses relative to single-breed accuracy of 0.49 [10]

Advanced Applications and Integration

Multi-Omics Integration

The G-matrix concept can be extended to incorporate multiple layers of biological information beyond genomics. Multi-omics integration combines genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic, and other molecular data to provide a more comprehensive view of the biological pathways underlying complex traits. Model-based integration techniques that capture non-additive, nonlinear, and hierarchical interactions across omics layers have shown consistent improvements in predictive accuracy over genomic-only models, particularly for complex traits [11].

Covariance-Adjusted Models

For populations with specific structures, such as backcross populations, covariance-adjusted models can improve prediction accuracy by accounting for marker correlations resulting from linkage disequilibrium. The Covariance-Adjusted Genomic BLUP (CAG-BLUP) incorporates a covariance matrix R developed for full sibs to capture marker correlations:

GCAG = ZRZ′ · (1/s), where s = 1′R1

Where R is the covariance matrix with elements rᵢⱼ = exp(-2dᵢⱼ) calculated using Haldane's mapping function, and dᵢⱼ is the genetic distance between markers in morgans [12].

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting appropriate genomic prediction approaches based on population structure, data availability, and trait complexity. Advanced applications include weighted GBLUP using GWAS information, covariance-adjusted models for structured populations, and multi-omics integration for complex traits.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for G-Matrix Construction and Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLUPF90 Suite | Mixed model analysis | Implements various BLUP models including GBLUP and ssGBLUP | Routine genetic evaluations; supports single-step approaches [9] |

| GCTA | Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis | Estimates variance components; constructs GRM; REML analysis | Heritability estimation; genetic parameter estimation [7] |

| PLINK | Genome Data Management | Quality control; data management; basic association analysis | SNP dataset filtering; MAF and HWE calculations [9] [7] |

| BGLR | Bayesian Regression | Bayesian generalized linear regression | Genomic prediction with various prior distributions [3] |

| PREGSF90 | Genomic relationship matrix construction | Computes G matrices following Method 1 of VanRaden | Preparation of genomic relationship matrices [9] |

| SWIM | Genotype Imputation | Haplotype-based imputation to whole genome sequence level | Increasing marker density from chip to sequence data [7] |

| FImpute | Genotype Imputation | Accurate genotype imputation using family and population information | Preparing high-density genotypes from various platforms [8] |

Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (G-BLUP) has become a cornerstone method in modern genetic evaluation for both plant and animal breeding, as well as in human genetics research. A critical component of the G-BLUP framework is the genomic relationship matrix (G-matrix), which quantifies the genetic similarities between individuals based on genome-wide marker data. The G-matrix fundamentally shifts the paradigm from pedigree-based inferred relatedness to marker-based realized relatedness, thereby capturing the true genetic relationships and inbreeding coefficients that arise from Mendelian sampling and historical recombination events. This document explores the theoretical foundations, construction methodologies, and practical implementations of G-matrices, with particular emphasis on how they overcome the limiting assumptions of traditional pedigree-based approaches. Framed within broader G-BLUP implementation research, this review serves as a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage genomic data for accurate genetic value prediction.

Theoretical Foundations of Genomic Relationship Matrices

From Pedigree to Genomic Relationships

Traditional pedigree-based relationship matrices (A-matrices) estimate relatedness using expected probabilities of identity by descent based on lineage information. These matrices operate under several simplifying assumptions, including random mating and the absence of selection, which are frequently violated in real populations. This can lead to inaccurate relatedness estimates, particularly for inbreeding coefficients, as pedigree methods cannot account for the random nature of allele transmission during meiosis [3].

The genomic relationship matrix (G-matrix) replaces these expected values with realized relatedness measured directly from molecular marker data. The basic form of the G-matrix is derived from a centered genotype matrix. Let M be an n × m matrix of genotype scores (coded as 0, 1, or 2 copies of a reference allele) for n individuals and m markers. The matrix is centered by subtracting P, a matrix containing twice the allele frequency (2pᵢ) for each locus i [3]. The unscaled G-matrix is then calculated as [3]:

To make this matrix comparable to the numerator relationship matrix A (which has an average diagonal of approximately 1 + F, where F is the inbreeding coefficient), a scaling factor is typically applied. A common scaling method divides by the sum of the expected variances across all loci [3] [13]:

This scaling ensures that the elements of G are approximately equivalent to the coancestry coefficients found in the A-matrix, thereby facilitating direct comparison and combination of genomic and pedigree information.

Capturing True Relatedness and Inbreeding

The G-matrix provides several advantages over pedigree-based approaches for quantifying relatedness and inbreeding:

Realized Relatedness: The G-matrix measures the actual proportion of the genome shared between individuals, which can differ significantly from the expected pedigree-based values due to recombination and random segregation during gamete formation [3]. This is particularly valuable for estimating the genetic relationships between individuals with incomplete or unknown pedigree records.

Detection of Inbreeding Depression: Diagonal elements of the G-matrix (Gᵢᵢ) reflect individual autozygosity—the proportion of the genome that is homozygous due to identity by descent. This provides a direct, genome-wide measure of inbreeding that is more accurate than pedigree-based estimates, especially in populations with complex kinship structures or selection history [3]. This accurate estimation is crucial for detecting and mitigating inbreeding depression in breeding programs.

Accounting for Population Structure: The construction of G inherently accounts for the population allele frequencies, making it more robust for analyzing structured populations where relatedness estimates might otherwise be confounded by stratification [3].

Methodological Approaches for G-Matrix Construction

Common G-Matrix Parameterizations

Several methodological variations exist for constructing G-matrices, primarily differing in how allele frequencies are estimated and how scaling factors are applied. The choice of method can significantly impact the accuracy of genomic predictions, particularly in populations with specific characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Relationship Matrix Construction Methods

| Method | Allele Frequency | Scaling Approach | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G05 [3] | Fixed at 0.5 for all markers | Variance-weighted | Does not require known allele frequencies; simple computation | Base population frequencies unknown; some genotypes missing |

| GOF [3] | Observed frequencies in the genotyped population | Variance-weighted | Currently the most widely used method; uses actual sample frequencies | Large, randomly sampled genotyped populations |

| GMF [3] | Average minor allele frequency | Variance-weighted | Compromise between G05 and GOF; uses population-level frequency | Base population unavailable; unbalanced data |

| GN [3] | Observed frequencies | Normalized by trace of numerator matrix | Ensures average diagonal close to 1; better corresponds to A-matrix | Integration with pedigree information; low inbreeding populations |

| GD [3] | Observed frequencies | Weighting by reciprocals of expected variances | Higher weight on rare alleles; accounts for unequal marker effects | Traits influenced by major genes; human genetic diseases |

Addressing Computational and Statistical Challenges

Singularity and Blending

When the number of genotyped animals (N_g) exceeds the number of markers (m), the G-matrix becomes singular (non-invertible), preventing its use in mixed model equations [14]. A common solution involves "blending" G with another positive definite matrix to ensure invertibility. The blended matrix G* is calculated as [15]:

Where K is typically either the pedigree-based relationship matrix for genotyped animals (A₂₂) or an identity matrix (I), and α and β are blending parameters (e.g., 0.95 and 0.05, or 0.99 and 0.01) [15]. Research on US Holstein populations has shown that blending G with 0.001I performs similarly to blending with 0.30A₂₂ but with significantly reduced computational requirements [15].

Single-Step GBLUP (ssGBLUP)

The single-step approach allows for the simultaneous analysis of genotyped and non-genotyped individuals by combining the pedigree-based relationship matrix A with the genomic relationship matrix G into a single matrix H [16] [13]. The inverse of H, which is needed for mixed model equations, can be efficiently computed as [16] [13]:

This approach eliminates the need for a multi-step evaluation process and allows genomic information to be implicitly imputed from genotyped to non-genotyped animals based on pedigree relationships [16] [13].

Algorithm for Proven and Young (APY)

For large genotyped populations, constructing and inverting G becomes computationally prohibitive. The APY algorithm partitions genotyped animals into core (c) and non-core (n) groups and enables the direct construction of Gâ»Â¹ without explicitly inverting the entire G matrix [13]. This results in a sparse matrix that significantly reduces computational demands while maintaining accuracy (correlations >0.99 with regular ssGBLUP) [13].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Comparative Evaluation Across Species

A comprehensive study evaluated the impact of different G-matrix construction methods on prediction accuracy across four species: pigs, bulls, wheat, and mice [3]. The experimental framework utilized the GBLUP model:

where y is the phenotype vector, X and Z are design matrices, b represents fixed effects, g is the random additive genetic effect ~N(0, Gσ²g), and e is the residual error ~N(0, Iσ²e) [3].

Table 2: Dataset Characteristics for Multi-Species G-Matrix Evaluation

| Species | Population Size | Marker Count | Traits Analyzed | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigs [3] | 820 | 44,580 SNPs | Backfat thickness, loin muscle area | GD matrix showed significant improvement |

| Bulls [3] | 5,024 | 42,551 SNPs | Milk fat %, milk yield, somatic cell score | Minimal G-matrix effect with large reference population |

| Wheat [3] | 599 | 1,279 DArT markers | Grain yield in four environments | Minimal differences between methods |

| Mice [3] | 1,814 | 10,346 polymorphic markers | Body mass index, body weight, body length | Minimal G-matrix effect |

The results demonstrated that the optimal G-matrix construction method is species-dependent. The GD matrix, which weights markers by the reciprocals of their expected variances, showed significant improvements for pig traits [3]. In contrast, most scaled G-matrices had minimal effects on prediction accuracy in mice, wheat, and bull populations [3]. For bull data, which had a large reference population size and high marker density, the choice of G-matrix had minimal impact on prediction accuracy, suggesting that the influence of G-matrix construction diminishes with sufficiently large and dense genomic datasets [3].

Protocol: Implementing GBLUP with BLUPF90 Suite

For researchers implementing GBLUP in practice, the following protocol provides a step-by-step guide using the widely-adopted BLUPF90 software suite [17]:

Data Preparation:

- Create a data file with columns for: animal ID, fixed effect(s), phenotype, and optional weight.

- Prepare a marker file containing all genotyped animals with their SNP genotypes.

- For standard GBLUP (all animals genotyped), create a dummy pedigree file where all animals have unknown parents. This results in Aâ»Â¹ = Aâ‚‚â‚‚â»Â¹ = I, which cancels out in the single-step equations, effectively yielding Hâ»Â¹ = Gâ»Â¹ [17].

Parameter File Specification:

- Use RENUMF90 to create an instruction file specifying the analysis parameters [17]:

Matrix Construction and Analysis:

- Run BLUPF90 with the parameter file generated by RENUMF90.

- The software will automatically construct the G-matrix using the specified method (default is similar to GOF).

- Solutions for breeding values and fixed effects are obtained by solving the mixed model equations.

Output Interpretation:

- Breeding values are provided for all genotyped animals in the solutions file.

- The accuracy of predictions can be calculated using approximation methods based on the diagonal elements of the mixed model equations [13].

Advanced Integration: DeepGBLUP

A novel algorithm called deepGBLUP has been developed to integrate deep learning networks with the GBLUP framework [18]. This approach uses locally-connected layers to capture marker effects while considering their distinct loci, then combines these with GBLUP-estimated additive, dominance, and epistatic genomic values [18]. In evaluations on Korean native cattle, deepGBLUP outperformed conventional GBLUP and Bayesian methods across diverse traits, marker densities, and training population sizes [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for G-Matrix Research

| Item | Function | Example Tools/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platforms | Generate genome-wide marker data | Illumina PorcineSNP60 BeadChip, Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip [3], DArT technology [3] |

| Quality Control Software | Filter and clean raw genotype data | PLINK1.9 [18] |

| Imputation Algorithms | Predict missing genotypes | Eagle v2.4 [18] |

| Genomic Prediction Software | Implement GBLUP/ssGBLUP models | BLUPF90 suite [17], BGLR R package [3] |

| Variance Component Estimation | Estimate genetic parameters | REML through BLUPF90 [17] |

| Relationship Matrix Tools | Construct and manipulate relationship matrices | PreGSf90 (part of BLUPF90 suite) |

| Indantadol hydrochloride | Indantadol hydrochloride, CAS:202914-18-9, MF:C11H15ClN2O, MW:226.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| gypsogenin 3-O-glucuronide | gypsogenin 3-O-glucuronide, CAS:105762-16-1, MF:C36H54O10, MW:646.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

G-Matrix Implementation Workflow

Single-Step GBLUP Conceptual Framework

The genomic relationship matrix represents a fundamental advancement in statistical genetics, effectively overcoming key assumption violations inherent in pedigree-based methods. By capturing realized rather than expected relatedness, the G-matrix provides more accurate estimates of both relatedness and inbreeding, leading to improved accuracy in genomic predictions. The optimal implementation of G-matrices requires careful consideration of construction methods, with the GD matrix showing particular promise for traits influenced by major genes, while traditional methods like GOF perform adequately in large, randomly mating populations. As genomic technologies continue to evolve, methodologies such as single-step GBLUP and advanced computational approaches like APY inversion and deepGBLUP integration will further enhance our ability to leverage genomic information for accurate genetic prediction across diverse species and breeding contexts.

Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP) has become a cornerstone of genetic evaluation in animal and plant breeding, as well as in human genetics. The central component of the GBLUP framework is the Genomic Relationship Matrix (G-matrix), which quantifies the genetic similarity between individuals based on genome-wide marker data rather than pedigree information. Among the various methods proposed for constructing this matrix, VanRaden's Method 1 has emerged as a standard approach due to its computational efficiency and theoretical properties. This formulation allows the G-matrix to be directly compatible with the classical numerator relationship matrix (A-matrix) used in traditional BLUP, facilitating its integration into established genetic evaluation systems. The accurate implementation of this matrix is critical for genomic prediction, inbreeding management, and the estimation of genetic parameters in breeding programs and genetic studies [3] [19] [20].

Mathematical Foundations

Core Formulation of VanRaden's Method 1

The standard genomic relationship matrix (G) according to VanRaden's Method 1 is calculated as follows:

G = (M - P)(M - P)' / 2∑(pj(1-pj))

Where:

- M is an

n × mmatrix of genotype scores, wherenis the number of individuals andmis the number of markers. Genotypes are typically coded as 0 (homozygous for allele A), 1 (heterozygous), and 2 (homozygous for allele B). - P is an

n × mmatrix where each columnjcontains the value2p<sub>j</sub>, wherep<sub>j</sub>is the frequency of the second allele (usually the alternative or minor allele) at locusjin the base population. - The denominator

2∑(p<sub>j</(1-p<sub>j</sub>)scales the matrix so that the relationships are comparable to the pedigree-based numerator relationship matrix [21] [19].

This formulation centers the genotype scores by subtracting twice the allele frequency, which effectively measures the deviation of an individual's genotype from the population mean. The scaling factor ensures that the expected variance of genetic relationships is consistent with the additive genetic variance under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Key Theoretical Properties

VanRaden's Method 1 possesses several important theoretical properties:

- It provides an unbiased estimate of the numerator relationship matrix when using base population allele frequencies

- The matrix is positive semi-definite, ensuring its mathematical validity in mixed model equations

- The average diagonal elements are approximately 1 + F, where F is the inbreeding coefficient, making it directly comparable to the pedigree-based relationship matrix

- It assumes equal variance contributions from all markers, which is consistent with the infinitesimal model of quantitative genetics [19] [20]

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Relationship Matrix Construction Methods

| Method | Key Formula | Allele Frequency Usage | Weighting of Markers | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VanRaden Method 1 (VR1) | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / 2∑pj(1-pj) | Base population frequencies | Equal variance contribution | Standard GBLUP |

| VanRaden Method 2 (VR2) | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / m, with locus-specific denominator | Base population frequencies | Inverse of expected heterozygosity | Emphasis on rare alleles |

| G05 | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / 2∑0.5(1-0.5) | Fixed at 0. for all markers | Equal variance, simple implementation | Unknown base population |

| GOF | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / 2∑pj(1-pj) with observed frequencies | Current population frequencies | Adjusted for current diversity | Compatibility with current kinship |

| GN | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / trace[(M-P)(M-P)']/n | Any frequency source | Average diagonal of 1 | Direct scaling to A-matrix |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Statistical Properties Across Methods

The choice of G-matrix construction method significantly impacts the statistical properties of the resulting matrix and its behavior in genomic prediction. VanRaden's Method 1 typically produces relationship estimates where both diagonal and off-diagonal elements are, on average, greater than pedigree-based coefficients when using fixed or base population allele frequencies. This method tends to be more efficient than pedigree-based relationships for managing inbreeding while maximizing genetic gain, particularly in small populations under optimum contribution selection (OCS) schemes [21] [19].

Research has demonstrated that genomic relationships were more efficient than pedigree-based relationships at managing inbreeding, with VR1 being slightly more efficient than VR2, though the difference was not always statistically significant. When comparing reference allele frequency sources, those computed from base animals were more efficient compared to frequencies computed from recent animals [21].

Prediction Accuracy Across Species

The performance of VanRaden's Method 1 varies across species and genetic architectures:

Table 2: Performance of VanRaden's Method 1 Across Species and Traits

| Species | Trait Category | Performance of VR1 | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy Cattle | Production traits (milk yield, fat) | High accuracy | Minimal impact of G-matrix choice with large reference populations |

| Swine | Litter size | Moderate to high accuracy | Correlation of 0.79 between EBV and GEBV |

| Plants (Wheat) | Grain yield | Variable accuracy | Species-specific optimization beneficial |

| Mouse | Body composition | High accuracy | Effective in controlled breeding designs |

| Korean Native Cattle | Carcass traits | State-of-the-art | Strong performance in GBLUP frameworks |

In cattle populations, one study found that the choice of G-matrix had minimal impact on prediction accuracy when the reference population size and genetic marker density reached a sufficient threshold. However, for populations with limited reference sizes or specific genetic architectures, the method of G-matrix construction remained important [3].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Implementation Protocol

Protocol 1: Construction of VanRaden's Method 1 G-Matrix

Genotype Data Preparation

- Obtain genotype data in the form of an

n × mmatrix M, wherenis the number of individuals andmis the number of markers - Code genotypes as 0, 1, or 2 representing the number of alternative alleles

- Perform quality control: exclude markers with minor allele frequency < 0.05, significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and high missing genotype rates

- Impute missing genotypes using appropriate algorithms (e.g., Eagle v2.4)

- Obtain genotype data in the form of an

Allele Frequency Calculation

- Estimate allele frequencies (pj) for each marker j

- For base population frequencies, use historical genotypes if available

- Alternatively, use the current population frequencies, though this may reduce compatibility with pedigree relationships

Matrix Construction

- Compute matrix P where each column j contains the value 2pj

- Calculate the difference matrix: Z = M - P

- Compute the scaling factor: s = 2Σj=1mpj(1-pj)

- Construct G-matrix: G = ZZ' / s

Quality Assessment

Application in Optimum Contribution Selection

Protocol 2: Implementation in Breeding Program with OCS

This protocol is adapted from studies on Icelandic Cattle populations [21]:

Population Structure Analysis

- Define the breeding population and selection candidates

- Genotype all selection candidates using appropriate SNP arrays

- Calculate the G-matrix using VanRaden's Method 1 with base population allele frequencies

Genetic Parameter Estimation

- Estimate variance components using REML with the G-matrix

- Calculate breeding values using GBLUP

- Define selection constraints based on inbreeding targets

OCS Implementation

- Apply optimization algorithms to maximize genetic gain while constraining the rate of inbreeding

- Use the G-matrix to calculate average kinship between potential matings

- Select parent combinations that maximize genetic gain while maintaining kinship below the desired threshold

Validation and Monitoring

- Monitor actual versus predicted genetic gain

- Track the rate of inbreeding accumulation

- Adjust selection constraints as needed based on population parameters

Computational Implementation

Workflow for G-Matrix Construction and Application

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for constructing and applying VanRaden's Method 1 G-matrix in genomic prediction:

Integration in Single-Step Genomic Evaluation

For populations where not all individuals are genotyped, VanRaden's Method 1 can be integrated into a single-step evaluation approach:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Resources for G-Matrix Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Key Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platforms | Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip, PorcineSNP60 BeadChip | Generate raw genotype data | Standardized SNP arrays ensure consistent coding |

| Quality Control Tools | PLINK 1.9, R/genetics packages | Filter markers by MAF, HWE, missingness | Critical for removing problematic variants |

| Imputation Software | Eagle v2.4, BEAGLE | Fill in missing genotypes | Improves marker completeness and matrix stability |

| Matrix Computation | R, Python NumPy, MATLAB | Perform matrix operations | Efficient handling of large matrices required |

| Variance Component Estimation | DMU, AIREML, BLUPF90 | Estimate genetic parameters | REML provides unbiased variance estimates |

| Specialized Packages | MoBPS, GMATRIX, EVA | Simulate breeding programs, optimize contributions | Specialized for advanced breeding applications |

| 2-Amino-3-Hydroxypyridine | 2-Amino-3-Hydroxypyridine, CAS:16867-03-1, MF:C5H6N2O, MW:110.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Methoxytryptamine hydrochloride | 5-Methoxytryptamine Hydrochloride|CAS 66-83-1 | 5-Methoxytryptamine hydrochloride is a potent, non-selective serotonin receptor agonist for neuroscience and psychopharmacology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Inbreeding Estimation

VanRaden's Method 1 can be used to estimate genomic inbreeding coefficients through the diagonal elements of the G-matrix. The inbreeding coefficient F for an individual i is calculated as:

FVR1 = Gii - 1

However, it is important to note that this measure differs from other genomic inbreeding coefficients. Compared to the Nejati-Javaremi allelic relationship matrix (FNEJ), which simply measures homozygosity, FVR1 gives greater weight to rare alleles, as rare homozygous genotypes contribute more to the inbreeding measure than common homozygous genotypes [20].

Weighted G-Matrices

Advanced implementations of VanRaden's Method 1 may incorporate marker weights to account for unequal variance contributions:

Gw = ZDZ'

Where D is a diagonal matrix containing weights for each marker. This approach can be useful when integrating prior information about marker effects or when dealing with traits influenced by major genes [22].

Compatibility with Pedigree Relationships

For optimal performance in single-step evaluations, the G-matrix should be compatible with the pedigree-based relationship matrix (A). This can be achieved by:

- Using base population allele frequencies when available

- Scaling G to have average diagonal elements equal to 1

- Blending G with A22 to avoid singularity: Gadj = wG + (1-w)A22, where w is typically 0.95 [19]

VanRaden's Method 1 represents a robust, theoretically sound approach for constructing genomic relationship matrices in GBLUP applications. Its mathematical formulation provides compatibility with traditional pedigree-based models while leveraging the rich information contained in genome-wide marker data. The method has demonstrated consistent performance across species and breeding contexts, particularly when implemented with appropriate allele frequency estimates and quality control procedures. As genomic selection continues to evolve, VanRaden's Method 1 remains a fundamental tool in the quantitative geneticist's toolkit, forming the foundation for more advanced methodologies including single-step evaluations, optimized breeding strategies, and comprehensive genetic analyses.

In modern genetics and breeding programs, accurately estimating the components of genetic variance—additive, dominance, and epistatic effects—is crucial for understanding complex trait architecture and predicting phenotypic outcomes. Traditional methods struggled to disentangle these components, but genomic approaches, particularly those utilizing Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (G-BLUP) with various genomic relationship matrices (G-matrices), now enable more precise estimation. These advancements allow researchers to partition the total genetic variance into its constituent parts, providing insights that inform selection strategies in animal and plant breeding, as well as human genetics. This protocol details the implementation of genomic models for variance component estimation, framed within broader research on G-BLUP and genomic relationship matrices.

Theoretical Foundation: Genetic Variance Components in Genomic Models

Genomic prediction models have revolutionized quantitative genetics by enabling the separation of genetic variance components using genome-wide marker information. In the context of hybrid crops, for example, a dedicated GCA-model (General Combining Ability model) allows the separation of general combining ability (GCA) into within-line additive effects and within-line additive-by-additive epistatic deviations, while the specific combining ability (SCA) can be split into dominance and across-groups epistatic deviations [23].

The additive genetic variance represents the sum of individual allele effects and forms the basis for estimating breeding values. Dominance variance arises from interactions between alleles at the same locus, while epistatic variance results from interactions between alleles at different loci. In standard genomic models, the covariance between hybrids can be analytically derived to account for additive substitution effects, dominance deviations, and epistatic deviations [23].

The genomic best linear unbiased prediction (G-BLUP) method serves as a cornerstone for this analysis, relying on the construction of a genomic relationship matrix (G-matrix) that quantifies the genetic similarity between individuals based on marker data [3] [24]. Different constructions of this matrix can significantly impact the accuracy of variance component estimation, particularly for traits with contrasting genetic architectures.

Computational Approaches and Model Specifications

G-BLUP Framework and G-Matrix Construction

The foundational G-BLUP model follows the specification:

y = Xb + Zg + e

Where y is the phenotypic vector, X is the design matrix for fixed effects (b), Z is the design matrix for random genetic effects (g), and e is the residual vector [3] [24]. The random genetic effects are assumed to follow a normal distribution: g ~ N(0, Gσ²g), where G is the genomic relationship matrix and σ²g is the genomic variance.

Multiple methods exist for constructing the G-matrix, each with distinct properties and applications. The choice of method depends on the population structure, genetic architecture of the trait, and available genomic data. The performance of these different G-matrices varies across species, with population structure being a key determining factor [3] [24].

Table 1: Methods for Genomic Relationship Matrix (G-matrix) Construction

| Method | Formula | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unscaled (MM') | G = MM' | Simple computation; counts shared alleles | Preliminary analysis; large, diverse populations |

| G05 | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / 2∑pᵢ(1-pᵢ) with pᵢ=0.5 | Assumes equal allele frequencies; standardized diagonal | When base population frequencies unknown |

| GOF | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / 2∑pᵢ(1-pᵢ) with pᵢ=observed | Uses observed allele frequencies; most widely used | General purpose; diverse populations |

| GMF | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / 2∑pᵢ(1-pᵢ) with pᵢ=mean MAF | Uses average minor allele frequency | Balanced approach for unknown base population |

| GN | G = (M-P)(M-P)' / k with k=trace of numerator | Normalized matrix; average diagonal close to 1 | Compatibility with pedigree matrices; low inbreeding |

| GD | G = (M-P)D(M-P)' with D=diagonal of expected variance weights | Weights markers by reciprocal of expected variance | Traits influenced by major genes; uneven marker effects |

Advanced Models for Variance Component Estimation

For hybrid breeding contexts, more sophisticated models have been developed that explicitly account for different variance components:

Model 1 (M1) - GCA Model: yᵢⱼ = μ + Eⱼ + gP1ᵢ + gP2ᵢ + eᵢⱼ

This model includes general combining ability effects from both parents but does not account for specific combining ability [25].

Model 2 (M2) - GCA + SCA Model: yᵢⱼ = μ + Eⱼ + gP1ᵢ + gP2ᵢ + gP1×P2ᵢ + eᵢⱼ

This extended model incorporates both general and specific combining ability, where gP1×P2 represents the interaction effect between parent 1 and parent 2 [25].

Model 3 (M3) - GCA + SCA + Environment Interaction Model: yᵢⱼ = μ + Eⱼ + gP1ᵢ + gP2ᵢ + gP1×P2ᵢ + gEP1ᵢⱼ + gEP2ᵢⱼ + gEP1×P2ᵢⱼ + eᵢⱼ

This comprehensive model accounts for all genetic effects and their interactions with environments, providing the most complete partitioning of variance components [25].

Experimental Protocol for Variance Component Estimation

Sample Preparation and Genotypic Data Processing

Materials and Reagents:

- Tissue samples for DNA extraction (leaf, blood, or saliva depending on species)

- DNA extraction kits

- SNP genotyping platforms (e.g., Illumina BeadChip, DArT technology)

- Quality control tools for genomic data

Protocol Steps:

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect tissue samples from all individuals in the breeding population or study cohort

- Extract DNA using standardized protocols appropriate for the species

- Quantify DNA concentration and quality using spectrophotometry

Genotyping and Quality Control:

- Genotype all samples using an appropriate SNP array or sequencing technology

- Perform quality control filtering: remove markers with call rate <95%, minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.05, and significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- Impute missing genotypes using appropriate algorithms (e.g., Beagle, FImpute)

- Format the genotype matrix M, where rows represent individuals and columns represent markers, coded as 0, 1, 2 for the number of minor alleles

Phenotypic Data Collection and Processing

Materials:

- Standardized measurement tools for target traits

- Environmental monitoring equipment

- Data recording systems

Protocol Steps:

Trait Measurement:

- Measure target traits of interest in replicated trials or environments

- Record environmental covariates that may influence trait expression

- For hybrid crops, ensure balanced representation of crosses between heterotic groups

Data Adjustment:

- Adjust raw phenotypic data for fixed effects (e.g., trial, location, block) using mixed models

- Calculate best linear unbiased estimators (BLUEs) for genotypes if needed

- For multi-environment trials, account for genotype-by-environment interaction

Model Implementation and Variance Component Estimation

Computational Tools:

- Statistical software with mixed model capabilities (R, ASReml, SAS)

- Specialized packages for genomic prediction (BGLR, sommer, rrBLUP)

- High-performance computing resources for large datasets

Protocol Steps:

G-matrix Construction:

- Choose appropriate G-matrix construction method based on population structure and trait architecture (refer to Table 1)

- Compute the genomic relationship matrix using the selected method

- Validate that the G-matrix properties are reasonable (diagonal elements ≈1, off-diagonal elements reflect relatedness)

Model Fitting:

- Implement the basic G-BLUP model for initial variance component estimation

- For hybrid crops, implement the GCA-model (M1) to separate within-line additive effects from epistatic deviations

- Fit extended models (M2, M3) to estimate dominance and epistatic variances

- Use restricted maximum likelihood (REML) for variance component estimation

Model Comparison and Validation:

- Compare models using information criteria (AIC, BIC) or cross-validation

- Perform cross-validation by partitioning data into training and validation sets

- Calculate predictive accuracy as the correlation between predicted and observed values in the validation set

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental protocol for disentangling genetic variance components:

Specialized Approaches for Specific Breeding Contexts

For Hybrid Crops (e.g., Maize):

- Ensure balanced representation of crosses between heterotic groups (e.g., Dent × Flint)

- Implement the GCA-model to appropriately separate additive from non-additive effects

- Use the specific combining ability (SCA) component to capture dominance and epistasis

For Backcross Populations:

- Consider specialized models like CAG-BLUP that account for correlated markers due to linkage disequilibrium

- Implement genomic-architecture-specific BLUP (GAS-BLUP) for traits with major genes

For Structured Populations with Admixture:

- Account for group-specific allele effects using multi-group GWAS approaches

- Include admixed individuals to disentangle local genomic differences from epistatic interactions

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Variance Component Estimation

After model fitting, the estimated variance components can be interpreted as follows:

- Additive Genetic Variance (σ²a): Represents the heritable portion of genetic variation attributable to average allele effects

- Dominance Variance (σ²d): Captures non-additive interactions between alleles at the same locus

- Epistatic Variance (σ²i): Represents non-additive interactions between alleles at different loci

- Residual Variance (σ²e): Includes environmental variance and measurement error

Table 2: Example Variance Component Estimates from a Maize Hybrid Study Using the GCA-Model

| Variance Component | Estimate | Percentage of Total Genetic Variance | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive (GCA) | 45.2 | 68.5% | Primary genetic effects determining breeding values |

| Dominance | 12.1 | 18.3% | Intra-locus allelic interactions |

| Epistatic | 8.7 | 13.2% | Inter-locus interactions |

| Total Genetic | 66.0 | 100% | Sum of all genetic effects |

| Residual | 34.5 | - | Environmental and error variance |

Advanced Analytical Approaches

For temporal analysis of genetic variance, the framework proposed by Sorensen et al. (2001) can be extended to marker-based models, allowing partitioning of genetic variance into genic variance and linkage disequilibrium components across different stages of a breeding program [26]. This approach involves:

- Fitting a marker-based model to the data

- Sampling realizations of marker effects from the fitted model

- Calculating the variance of sampled genetic values by time and genome partitions

This analysis can reveal how different population processes (selection, drift) change the genome over time and affect the sustainability of breeding programs.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Variance Component Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platforms | Illumina SNP BeadChips (PorcineSNP60, BovineSNP50), DArT technology | Genome-wide marker genotyping for relationship matrix construction |

| Statistical Software | R/BGLR package, ASReml, SAS, sommer package | Implementation of mixed models for variance component estimation |

| Quality Control Tools | PLINK, VCFtools, TASSEL | Filtering and processing of genomic data |

| Reference Datasets | Publicly available maize (CIMMYT), cattle (VIT), mouse datasets | Benchmarking and method validation |

| Computational Resources | High-performance computing clusters, cloud computing platforms | Handling large-scale genomic data and computationally intensive models |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Challenges and Solutions:

- Inflated Additive Variance Estimates: This may occur when using standard models instead of the GCA-model in hybrid crops. Solution: Implement the GCA-model which appropriately separates additive from non-additive components [23].

- Low Precision of Epistatic Variance Estimates: Often due to limited sample size or genetic diversity. Solution: Increase population size and ensure balanced representation of crosses.

- Computational Limitations: Large datasets with high marker density can be computationally demanding. Solution: Use dimensionality reduction approaches like singular value decomposition (SVD) of marker genotypes [26].

- Model Convergence Issues: Can occur with complex models including multiple variance components. Solution: Use Bayesian approaches with appropriate priors or simplify the model structure.

Disentangling genetic variance into additive, dominance, and epistatic components is essential for understanding the genetic architecture of complex traits and optimizing breeding strategies. The genomic prediction frameworks outlined in this protocol, particularly those utilizing various G-matrix constructions and specialized models like GCA-model for hybrid crops, provide powerful tools for this purpose. The choice of appropriate models based on the breeding context and population structure is crucial for accurate variance component estimation. As genomic technologies continue to advance, these approaches will become increasingly refined, enabling more precise dissection of genetic variance components across diverse species and breeding programs.

Building and Implementing Genomic Relationship Matrices in Practice

Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP) is a cornerstone method in modern genomic prediction, widely used in animal and plant breeding as well as human genetics [3]. Unlike traditional BLUP, which relies on pedigree information, GBLUP utilizes genome-wide genetic markers to construct a genomic relationship matrix (G-matrix). This matrix directly reflects the genetic similarity between individuals based on their DNA profiles, leading to more accurate estimates of breeding values by better capturing Mendelian sampling deviations [3] [24]. The accuracy of predicting breeding values using genomic data has been shown to be significantly higher than that achieved using genealogical records alone [3]. The general GBLUP model is represented as:

y = Xb + Zg + e

where y is the phenotypic vector, X is the design matrix for fixed effects (b), Z is the design matrix for random additive genetic effects (g), and e is the random residual vector [3] [24]. The random effect g is assumed to follow a normal distribution ( N(0, G\sigmag^2) ), where ( \sigmag^2 ) is the genomic additive variance and G is the genomic relationship matrix [3] [24]. The construction of the G-matrix is therefore a critical step that significantly influences the accuracy of genomic predictions [3] [19].

Core Mathematical Framework for G-Matrix Construction

Foundation and Common Formula

The construction of genomic relationship matrices begins with a genotype matrix M, where entries correspond to the number of minor alleles (0, 1, or 2) for each individual and each genetic marker [3] [24]. The most fundamental approach involves a simple cross-product, resulting in the matrix MM′, which counts alleles shared between individuals [3].

A more refined general formula, which forms the basis for several major methods, centralizes the genotype matrix using allele frequencies and scales it to be comparable to the pedigree-based relationship matrix (A-matrix) [3] [24] [19]. This formula is expressed as:

[ G = \frac{(M - P)(M - P)'}{2\sum{i=1}^{m} pi(1-p_i)} ]

Here, M is the ( n \times m ) genotype matrix (( n ) individuals, ( m ) markers), P is a matrix where each column ( i ) contains the value ( 2pi ) (( pi ) is the frequency of the second allele at locus ( i )), and the denominator scales the matrix [3] [24] [19]. The term ( (M - P) ) centers the allele effects around zero [3]. The primary differences between methods revolve around the choice of allele frequency ( p_i ) and the scaling approach [3].

Methodologies and Algorithmic Variations

Table 1: Summary of Major G-Matrix Construction Methods

| Method | Allele Frequency (páµ¢) | Key Feature | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| G05 | Fixed at 0.5 for all markers [3] [19] | Does not require known allele frequencies; simple computation [3] | Base population when allele frequencies are unknown [3] |

| GOF | Observed allele frequency from the genotyped population [3] [19] | Most widely used method; average off-diagonal elements close to 0 [3] [19] | Standard applications with representative population data [3] |

| GMF | Average minor allele frequency across all markers [3] | Uses a single frequency value for all markers [3] | Base population when some allele frequencies are unknown [3] |

| GN | Varies (often observed frequency) | Scaled to have an average diagonal of 1 [3] [19] | Better compatibility with A-matrix; low inbreeding [3] [19] |

| GD | Varies (often observed frequency) | Weights markers by reciprocals of expected variance [3] | Traits influenced by major genes or human genetic diseases [3] |

G05 (Allele Frequency Fixed at 0.5): This method assumes all allele frequencies are 0.5, effectively treating every locus as equally informative [3] [19]. It does not require prior knowledge of allele frequencies, making it suitable for situations where the base population is unavailable or genotypes are missing [3]. A potential limitation is that it may overestimate relationships when the actual allele frequencies deviate substantially from 0.5 [19].

GOF (Observed Allele Frequency): This approach uses the actual observed allele frequencies from the genotyped population [3] [19]. It is currently the most widely used method in practice [3]. A key characteristic is that the average of its off-diagonal elements is approximately zero, reflecting the assumption that the average genetic relationship between unrelated individuals in a population is zero [19].

GMF (Average Minor Allele Frequency): Similar to G05, this method employs a single frequency value for all markers but uses the average minor allele frequency instead of 0.5 [3]. This provides a slightly more population-specific adjustment than G05 while maintaining computational simplicity [3].

GN (Normalized Matrix): This method applies a normalization step to ensure the average of the diagonal elements is approximately 1, making it more directly comparable to the pedigree-based relationship matrix (A) [3] [19]. The general formula is:

[ G_N = \frac{(M - P)(M - P)'}{\text{trace}[(M - P)(M - P)'] / n} ]

where ( n ) is the number of genotyped individuals [3] [19]. This scaling helps control estimates of additive variance, particularly with smaller datasets [3].

GD (Variance-Weighted Matrix): This method addresses a key limitation of the previous approaches—the assumption that all markers contribute equally to genetic variation [3]. Instead, it weights markers by the reciprocals of their expected variance, allowing markers with larger effects to contribute more strongly to the relationship estimates [3]. This is particularly beneficial for traits influenced by genes of major effect [3].

Comparative Performance Across Species

A comprehensive 2025 study systematically evaluated these G-matrix methods across four species (pigs, bulls, wheat, and mice), revealing that optimal method choice is highly species-dependent [3] [27] [24].

Table 2: Performance of G-Matrix Methods Across Different Species

| Species | Sample Size | Markers | Optimal Method(s) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pig | 820 | 44,580 | GD [3] | GD showed significant prediction accuracy improvements for traits like backfat and loin muscle area [3] |

| Bull | 5,024 | 42,551 | All methods similar [3] | G-matrix choice had minimal impact with large reference population and high marker density [3] |

| Wheat | 599 | 1,279 | Minimal differences [3] | Most scaled G-matrices showed minimal effects compared to unscaled baseline [3] |

| Mice | 1,814 | 10,346 | Minimal differences [3] | Scaled G-matrices showed minimal effects on prediction accuracy [3] |

The study found that population structure and dataset scale significantly influence method performance [3]. For bull data, which had the largest population size and high marker density, the choice of G-matrix construction method had minimal impact on prediction accuracy, suggesting that the influence of G-matrix construction diminishes when reference population size and genetic marker density reach a sufficient threshold [3]. Conversely, in pigs, the GD matrix demonstrated significant advantages, likely because the studied traits were influenced by genes with major effects [3]. For mice and wheat with smaller datasets, most scaled G-matrices showed minimal effects compared to the original unscaled matrix [3].

Experimental Protocols for G-Matrix Implementation

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Materials:

- Genotype Data: Raw intensity files or pre-called genotypes from platforms such as Illumina PorcineSNP60 BeadChip or Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip [3] [19].

- Quality Control Software: PLINK, R/Bioconductor packages, or custom scripts for genotype filtering [19].

- Computing Resources: Workstation or high-performance computing cluster with sufficient memory for large matrix operations [3].

Procedure:

- Genotype Calling: Convert raw intensity data to genotype calls (0, 1, 2) using platform-specific algorithms [3].

- Marker Filtering: Remove markers with:

- Individual Filtering: Remove individuals with:

- High missing genotype rate (> 10%)

- Unusual heterozygosity rates indicating potential sample contamination

- Data Formatting: Convert filtered genotypes to a standardized numeric matrix format (M-matrix) for G-matrix computation [3].

G-Matrix Construction Workflow

G-Matrix Construction Workflow

Procedure:

- Method Selection: Choose the appropriate G-matrix construction method based on population characteristics and research objectives (refer to Table 1 for guidance) [3].

- Frequency Calculation:

- Matrix Centralization: Compute ( M - P ), where P contains columns of ( 2p_i ) [3] [24]

- Cross-Product Calculation: Compute ( (M - P)(M - P)' ) [3]

- Scaling Application:

- Compatibility Adjustment: For single-step applications, blend G with the pedigree relationship matrix ( A{22} ) using: ( G = wGr + (1 - w)A_{22} ), where w is typically 0.95-0.98 [19]

Validation and Evaluation Protocol

Procedure:

- Comparison with Pedigree Relationships: Calculate summary statistics (mean, variance) for diagonal and off-diagonal elements of G and compare with the pedigree-based relationship matrix (A) [19]. Well-scaled matrices should have similar means [19].

- Genomic Prediction Accuracy: Implement GBLUP using the different G-matrices and evaluate prediction accuracy through:

- Variance Component Estimation: Use REML procedures to estimate variance components with different G-matrices and compare estimates [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Arrays | Illumina PorcineSNP60 BeadChip [3] [19] | ~60,000 SNP markers for pigs | Porcine genomic studies |

| Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip [3] | ~54,000 SNP markers for cattle | Bovine genomic studies | |

| Software Tools | R Statistical Environment with BGLR package [3] | Implementation of GBLUP and Bayesian methods | Genomic prediction analysis |

| PLINK [19] | Genome association analysis toolset | Genotype quality control and basic analysis | |