Genotype to Phenotype Prediction: Overcoming Biological Complexity with Machine Learning and Cross-Species Data

This article explores the critical challenges and advanced methodologies in predicting phenotypic outcomes from genotypic data, a cornerstone of modern precision medicine and drug development.

Genotype to Phenotype Prediction: Overcoming Biological Complexity with Machine Learning and Cross-Species Data

Abstract

This article explores the critical challenges and advanced methodologies in predicting phenotypic outcomes from genotypic data, a cornerstone of modern precision medicine and drug development. We examine the fundamental gap between statistical associations and biological mechanisms, highlighting how cross-species differences and non-linear genetic interactions limit predictability. The review details how machine learning frameworks, including Random Forest and explainable AI (XAI), are revolutionizing prediction accuracy by integrating multimodal data from genomics, transcriptomics, and phenomics. We address key optimization strategies for tackling dataset bias and improving model interpretability, and present standardized validation frameworks for benchmarking algorithmic performance. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides a comprehensive roadmap for developing more accurate, clinically relevant genotype-to-phenotype models to enhance therapeutic safety and efficacy.

The Fundamental Gap: Why Genotype to Phenotype Prediction Remains a Core Challenge in Biology

A foundational challenge in genetics is accurately predicting complex traits and diseases from genetic information. For decades, much of genetic epidemiology has been guided by a simplifying assumption of linear additivity, where phenotypic outcomes are modeled as the cumulative sum of individual genetic variant effects [1] [2]. While this paradigm has enabled the discovery of thousands of trait-associated variants through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), it fundamentally overlooks the complex biological reality encapsulated by non-linearity, pleiotropy, and epistasis. The genotype-phenotype map is not a simple linear function but a complex network of interacting elements whose relationships shape evolutionary trajectories, disease risk, and treatment outcomes [3] [4] [5].

The limitations of linear models become particularly evident when considering that global estimators like genetic correlations are entirely uninformative about the underlying shape of bivariate genetic relationships, potentially masking significant nonlinear dependencies [1]. Furthermore, the widespread assumption that phenotypes arise from the cumulative effects of many independent genes fails to account for the dependent and nonlinear biological relationships that are now increasingly recognized as fundamental to accurate phenotype prediction [2]. As we move toward precision medicine and improved genomic selection in agriculture, understanding and modeling these complex genetic architectures becomes paramount for enhancing predictive accuracy and clinical utility.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Non-Linearity in Genetic Effects

Non-linearity in genetics manifests when the relationship between genetic variants and phenotypic outcomes does not follow a straight-line pattern. This encompasses U-shaped or J-shaped associations where both low and high levels of a genetic predisposition are associated with adverse outcomes, as observed in the relationships between body mass index (BMI) and depression, and between sleep duration and mental health [1]. These nonlinear associations mean that genetic effects estimated across the entire phenotypic spectrum may cancel each other out, leading to misleading null findings in linear models. For instance, both short and long sleep duration are associated with depression symptoms, while average sleep duration shows no genetic correlation, indicating opposing effects that neutralize each other in linear aggregate models [1].

Pleiotropy: One Variant, Multiple Effects

Pleiotropy occurs when a single genetic polymorphism affects two or more distinct phenotypic traits [5]. We can distinguish between:

- True pleiotropy, where a polymorphism directly influences multiple traits either independently ("horizontal pleiotropy") or through a mediating pathway ("mediating pleiotropy")

- Apparent pleiotropy, which arises when different polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium (LD) independently affect different traits, creating the illusion of a single pleiotropic variant [5]

Pleiotropy is not uniformly distributed across the genome; some genes are highly pleiotropic, affecting many traits, while others have more limited effects [5]. Understanding the structure of pleiotropy is crucial for disentangling shared genetic architectures of comorbid diseases and anticipating unintended consequences when targeting specific pathways.

Epistasis: Non-Linear Interactions Between Variants

Epistasis refers to non-linear interactions between genetic polymorphisms that affect the same trait, where the effect of one genetic variant depends on the presence or absence of other variants [3] [4] [5]. Two primary forms include:

- Functional epistasis: Inter-dependency of biological functionality between genomic regions

- Statistical epistasis: Deviations from additivity in statistical models that result in changes to phenotypic variation [6]

A particularly important challenge in human genetics is distinguishing genuine biological epistasis from joint tagging effects, where apparent interactions arise because multiple variants tag the same causal variant due to linkage disequilibrium [6]. Epistasis can significantly alter evolutionary trajectories by opening or closing adaptive paths and collectively shifting the entire distribution of fitness effects of new mutations [4].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Non-Linear Genetics

| Concept | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linearity | Non-straight-line relationship between genetic variants and phenotypes | Reveals complex dependencies masked by linear models; explains U/J-shaped associations |

| Pleiotropy | Single genetic variant affecting multiple distinct traits | Connects seemingly unrelated traits; reveals shared biological pathways |

| Epistasis | Interaction between genetic variants where effect of one depends on others | Shapes evolutionary trajectories; alters distribution of fitness effects |

Methodological Approaches for Detecting Non-Linearity

Trigonometric Methods for Bivariate Genetic Relationships

Novel statistical approaches based on trigonometry have been developed to infer the shape of non-linear bivariate genetic relationships without imposing linear assumptions. The TriGenometry method works by performing a series of piecemeal GWAS of segments of a continuous trait distribution and estimating genetic correlations between these GWAS and a second trait [1]. The methodological workflow can be summarized as follows:

- Binning: Divide a continuous trait (e.g., BMI) into 30 quantile-based bins to ensure sufficient sample size in each bin

- Pairwise GWAS: Perform GWAS for all pairwise combinations of bins (435 comparisons for 30 bins)

- Genetic Correlation Estimation: Estimate genetic correlations between each bin-pair GWAS and an external trait

- Trigonometric Transformation: Convert genetic correlations to angles and calculate estimated distances on the second trait

- Function Fitting: Use cubic spline or 5th-degree polynomial functions to interpolate the shape of the relationship [1]

This approach has successfully revealed non-linear genetic relationships between BMI and psychiatric traits (depression, anorexia nervosa), and between sleep duration and mental health outcomes (depression, ADHD), while finding no underlying nonlinearity in the genetic relationship between height and psychiatric traits [1].

Deep Learning and Hybrid Modeling

Deep learning approaches offer a powerful framework for detecting non-linearity without prior assumptions about the data structure. A promising hybrid model (DLGBLUP) combines traditional genomic best linear unbiased prediction (GBLUP) with deep learning, using the GBLUP output and enhancing predicted genetic values by accounting for nonlinear genetic relationships between traits using deep learning [7]. When applied to simulated data with nonlinear genetic relationships between traits, DLGBLUP consistently provided more accurate predicted genetic values for traits with strong nonlinear relationships and enabled greater genetic progress over multiple generations of selection compared to standard GBLUP [7].

However, the application of neural networks to polygenic prediction presents challenges. A comprehensive evaluation of deep-learning-based approaches found only small amounts of nonlinear effects in real traits from the UK Biobank, with neural network models generally being outperformed by linear regression models [6]. This highlights the technical difficulty of distinguishing genuine epistasis from confounding joint tagging effects due to linkage disequilibrium.

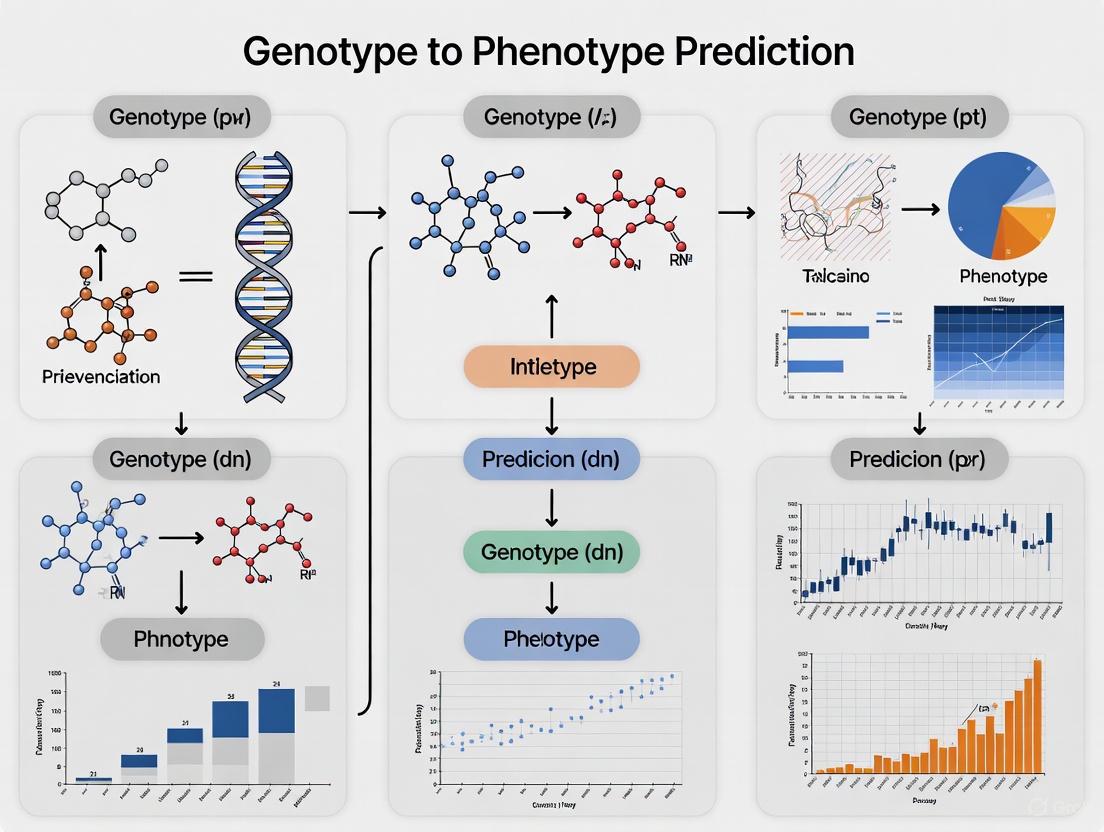

Diagram 1: Methods for detecting non-linearity. Two complementary approaches for identifying non-linear genetic relationships.

Uncertainty Quantification in Non-Linear Prediction

Accurately quantifying uncertainty in predicted phenotypes from polygenic scores is essential for reliable clinical interpretation. PredInterval is a nonparametric method for constructing well-calibrated prediction intervals that is compatible with any PGS method and relies on information from quantiles of phenotypic residuals through cross-validation [8]. In analyses of 17 traits, PredInterval was the sole method achieving well-calibrated prediction coverage across traits, offering a principled approach to identify high-risk individuals using prediction intervals and leading to substantial improvements in identification rates compared to existing approaches [8].

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Non-Linear Genetic Analysis

| Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TriGenometry | Trigonometric transformation of genetic correlations between trait segments | Bivariate trait relationships (e.g., BMI-depression) | Detects shape of relationship; minimal prior assumptions | Requires continuous trait; computationally intensive |

| Deep Learning Hybrid (DLGBLUP) | Neural networks to capture non-linearity in traditional model outputs | Multitrait genomic prediction | Detects complex patterns; integrates with existing methods | Risk of detecting joint tagging effects rather than biological epistasis |

| PredInterval | Nonparametric prediction intervals using phenotypic residuals | Uncertainty quantification for any PGS method | Well-calibrated coverage; identifies high-risk individuals | Does not directly model biological mechanisms |

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Non-Linear Genetic Relationships in Human Complex Traits

Application of trigonometric methods to data from approximately 450,000 individuals in the UK Biobank has revealed significant non-linear genetic dependencies in several important trait relationships:

- The relationship between BMI and depression follows a nonlinear pattern, with genetic effects varying across the BMI spectrum [1]

- Similarly, BMI and anorexia nervosa exhibit a nonlinear genetic relationship [1]

- Sleep duration and depression show a U-shaped association where both short and long sleep duration are genetically correlated with depression, while average sleep duration shows no correlation [1]

- Sleep duration and ADHD also demonstrate a nonlinear genetic relationship [1]

- In contrast, the genetic relationship between height and psychiatric traits showed no evidence of nonlinearity [1]

These findings demonstrate that genetic associations are not uniform across the phenotypic spectrum and challenge the assumption of linearity in genetic epidemiology. They further suggest that global estimators like genetic correlations can mask important complexities in genetic relationships, potentially explaining contradictory findings in the literature regarding directions of association [1].

Epistasis in Model Organisms and Microbial Evolution

Studies in model organisms and microbial systems have provided compelling evidence for the ubiquity and evolutionary significance of epistasis:

- In HIV-1 evolution, epistasis increases the pleiotropic degree of single mutations and provides modularity to the genotype-phenotype map of drug resistance, with modules of epistatic pleiotropic effects matching phenotypic modules of correlated replicative capacity among drug classes [3]

- Diminishing-returns epistasis is commonly observed in microbial evolution experiments, where beneficial mutations tend to be less beneficial in fitter genetic backgrounds, explaining patterns of declining adaptability in evolving populations [4]

- Increasing-costs epistasis has been documented in yeast, whereby deleterious insertion mutations tend to become more deleterious over the course of evolution, reducing mutational robustness [4]

- Deep mutational scanning studies of proteins frequently observe global epistasis, where mutations have additive effects on an unobserved biophysical property that maps nonlinearly to the observed phenotype [4]

A striking difference emerges between model organisms and humans: while epistasis is commonly observed between polymorphic loci associated with quantitative traits in model organisms, it is rarely detected for human quantitative traits and common diseases [5]. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in statistical power, the ability to control genetic background and environment in model organisms, or fundamental differences in genetic architecture.

Pleiotropy Across Biological Systems

Large-scale analyses across multiple species have revealed the ubiquity of pleiotropy:

- In Drosophila melanogaster, P-element insertional mutations have been shown to affect multiple organismal quantitative traits, with significant variation in the degree of pleiotropy across genes [5]

- The yeast deletion collection has been used to quantify pleiotropy through gene-by-environment interactions, demonstrating that most mutations affect multiple traits but with varying degrees of pleiotropy [5]

- In laboratory mice, genome-wide mutagenesis coupled with high-throughput phenotyping has revealed widespread pleiotropic effects on organismal-level phenotypes [5]

- Studies of gene expression as molecular phenotypes have shown that most genetic mutations affect the expression of multiple genes, indicating extensive pleiotropy at the molecular level [5]

These findings consistently show that pleiotropic effects are ubiquitous but not uniform—some genes are highly pleiotropic while others have more limited effects—and this distribution has important implications for evolutionary processes and disease risk.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank Data | Population-scale dataset | Provides genetic and phenotypic data for ~500,000 individuals | Large-scale discovery of non-linear genetic relationships in human complex traits [1] [6] |

| HapMap 3 Reference Set | Curated variant panel | Reference for genome-wide association studies | Controls for population structure in GWAS; used in TriGenometry method [1] |

| TriGenometry R Package | Software tool | Implements trigonometric method for detecting non-linear bivariate genetic relationships | Analysis of non-linear genetic dependencies between trait pairs [1] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Computational libraries | Enable implementation of neural network models for genetic data | Modeling complex non-linear relationships in genotype-phenotype maps [6] [7] |

| PredInterval | Statistical method | Constructs calibrated prediction intervals for polygenic scores | Uncertainty quantification in phenotype prediction [8] |

| Yeast Deletion Collection | Mutant library | Comprehensive set of gene knockout strains | Systematic assessment of pleiotropic effects across environments [5] |

| Drosophila P-element Insertion Collection | Mutant library | Genome-wide collection of insertion mutations | High-throughput phenotyping for pleiotropy quantification [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Detecting Non-Linear Genetic Relationships Using Trigonometric Methods

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing the TriGenometry approach to detect non-linear bivariate genetic relationships [1]:

Sample and Data Requirements:

- Genome-wide genotyping data for a large cohort (minimum N ≈ 10,000, ideally >100,000)

- A continuous target trait (e.g., BMI, sleep duration)

- A secondary trait (binary, ordinal, or continuous) of interest

Procedure:

- Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Apply standard GWQC filters to genetic data

- Adjust continuous trait for covariates (age, sex, principal components)

- Ensure secondary trait is appropriately coded

Binning of Continuous Trait

- Divide the continuous trait distribution into 30 quantile-based bins

- Ensure sufficient sample size in each bin (minimum N > 100)

- Calculate the median value of the trait in each bin

Pairwise GWAS

- For each of the 435 possible pairs of bins, perform a GWAS comparing the two bins

- Use the model:

px_bin_i = 1; x_bin_j = 0 = β0 + β1 * SNP + e - Apply standard GWAS quality control and significance thresholds

Genetic Correlation Estimation

- For each bin-pair GWAS, estimate genetic correlation with the secondary trait

- Use LD score regression or similar methods

- Record both the genetic correlation and distance between bin medians

Trigonometric Transformation

- Transform genetic correlations to angles:

angle = 90 - acos(cor/dx) * 180/Ï€ - Calculate estimated distance on secondary trait:

dy = tan(angle/180 * π) * dx

- Transform genetic correlations to angles:

Function Fitting and Visualization

- Fit a cubic spline or 5th-degree polynomial to the set of paired distances

- Visualize the resulting function to interpret the shape of the relationship

- Assess statistical significance through permutation testing

Interpretation:

- U-shaped or J-shaped curves indicate non-linear relationships where both extremes of the continuous trait are associated with the secondary trait

- Monotonic curves suggest linear relationships

- Flat curves indicate no relationship

Protocol for Evaluating Epistasis Using Neural Networks

This protocol describes an approach for detecting genuine epistasis while controlling for joint tagging effects [6]:

Sample and Data Requirements:

- Genotype data with appropriate LD structure information

- Phenotypic measurements

- Training, validation, and test partitions (recommended ratio: 6:2:2)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Partitioning

- Split data into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets

- Apply quality control filters to genetic data

- Adjust phenotypes for relevant covariates

LD-adjusted SNP Weighting

- Calculate LD-aware per-SNP PGS coefficients from a reference method

- Multiply these weights into the NN input to control for joint tagging effects

- This step is crucial for distinguishing genuine epistasis from LD artifacts

Neural Network Architecture Specification

- Design both linear (without activation functions) and nonlinear (with activation functions) NN models

- Use identical architectures except for the presence/absence of nonlinear activation functions

- Include appropriate regularization to prevent overfitting

Model Training and Validation

- Train both linear and nonlinear models on the training set

- Tune hyperparameters using the validation set

- Monitor for overfitting and convergence

Performance Comparison

- Evaluate both models on the held-out test set

- Compare predictive performance using appropriate metrics (r², AUC, etc.)

- Significant improvement in nonlinear models suggests genuine epistatic effects

Interpretation and Validation

- Perform statistical testing on the performance difference

- Use permutation approaches to establish significance thresholds

- Interpret findings in the context of known biology and potential confounding

Discussion and Future Directions

The evidence for non-linearity, pleiotropy, and epistasis challenges the additive linear model that has dominated complex trait genetics for decades. These phenomena have profound implications for genotype to phenotype prediction, affecting everything from the design of GWAS studies to the clinical application of polygenic scores.

The detection of non-linear genetic relationships between traits like BMI and mental health outcomes suggests that current genetic correlation estimates may substantially oversimplify the true genetic architecture of complex traits [1]. This has direct implications for pleiotropy analysis, as apparent genetic correlations between traits may vary across the phenotypic spectrum rather than representing uniform relationships. Understanding the shape of these relationships could improve risk prediction models by accounting for context-dependent genetic effects.

The discrepancy between the prevalence of epistasis in model organisms versus humans remains a puzzle [5]. Possible explanations include differences in statistical power, the impact of linkage disequilibrium structure in human populations, greater environmental heterogeneity in humans, or fundamental differences in genetic architecture. Resolving this discrepancy represents an important frontier in genetics research.

Methodologically, future advances will likely come from improved integration of functional genomics data with statistical approaches, better methods for distinguishing biological epistasis from technical artifacts, and the development of more powerful non-linear modeling techniques that can scale to biobank-sized datasets. The integration of deep learning with traditional genetic models shows particular promise for capturing complex genetic relationships while maintaining interpretability [7].

As we move beyond linear assumptions, we must also develop new frameworks for clinical translation of these more complex models. This includes methods for uncertainty quantification like PredInterval [8], approaches for visualizing and interpreting non-linear relationships, and guidelines for applying these models in personalized medicine and public health contexts.

In conclusion, embracing the complexity introduced by non-linearity, pleiotropy, and epistasis represents both a formidable challenge and a tremendous opportunity for improving our understanding of the genotype-phenotype map. By developing and applying methods that capture these phenomena, we can build more accurate predictive models, gain deeper insights into biological mechanisms, and ultimately enhance the utility of genetics in medicine and public health.

The fundamental challenge in modern genetics lies in accurately predicting phenotypic outcomes from genotypic information. While technological advances have generated unprecedented volumes of genomic data, our ability to translate these data into mechanistic understanding remains limited. This gap is epitomized by the "black box problem," where statistical associations identified through machine learning and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) fail to reveal underlying biological mechanisms. The field now stands at a crossroads, balancing the powerful predictive capabilities of data-driven approaches with the fundamental scientific need for causal explanation.

The expansion of large-scale biobanks has stimulated extensive work on predicting complex human traits such as height, body mass index, and coronary artery disease [9]. These resources have enabled researchers to ask whether big data can finally shrink the missing heritability gap that has long plagued complex trait genetics [9]. However, as the volume of data grows, so does the complexity of the models required to analyze it, often at the expense of interpretability. This whitepaper examines the critical distinction between statistical association and mechanistic understanding in genotype-to-phenotype research, providing frameworks for bridging this divide through innovative methodologies that maintain predictive power while enhancing biological interpretability.

The Limits of Correlation: Statistical Associations in Complex Trait Genetics

The Dominance of Association Studies

Genome-wide association studies have identified thousands of loci linked to complex traits, but they have historically concentrated on small variants, mainly single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), due to constraints in detecting larger, more complex variants [10]. This approach has yielded valuable insights but has proven insufficient for complete phenotypic prediction. The primary limitation of conventional GWAS is their focus on correlation rather than causation, which leaves researchers with statistical associations that lack mechanistic explanations.

The problem is further compounded by the fact that statistical associations, no matter how strong, do not necessarily imply causality. Spurious correlations can arise from population stratification, cryptic relatedness, or technical artifacts. Furthermore, even genuine associations may reflect indirect effects or be influenced by confounding variables not accounted for in the analysis. This limitation has significant implications for translating genetic discoveries into biological insights and therapeutic applications.

The Structural Variant Blind Spot

Recent research has demonstrated that focusing exclusively on SNPs provides an incomplete picture of the genetic architecture of complex traits. A landmark study involving near telomere-to-telomere assemblies of 1,086 natural yeast isolates revealed that inclusion of structural variants (SVs) and small insertion–deletion mutations improved heritability estimates by an average of 14.3% compared with analyses based only on single-nucleotide polymorphisms [10]. This finding indicates that a significant portion of "missing heritability" may reside in these more complex genomic variants that have been historically challenging to detect and characterize.

Table 1: Impact of Different Variant Types on Phenotypic Heritability in Yeast

| Variant Type | Frequency of Trait Association | Pleiotropy Level | Average Heritability Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Small Insertion-Deletion Mutations (Indels) | 1.2x SNPs | 1.1x SNPs | +7.2% |

| Structural Variants (SVs) | 1.8x SNPs | 1.6x SNPs | +14.3% |

| Presence-Absence Variations (PAVs) | 1.7x SNPs | 1.5x SNPs | +12.1% |

The study further found that structural variants were more frequently associated with traits and exhibited greater pleiotropy than other variant types [10]. Notably, the genetic architecture of molecular and organismal traits differed markedly, suggesting that different biological processes may be differentially influenced by various classes of genetic variation. These findings underscore the limitation of approaches that focus exclusively on one type of genetic variant and highlight the need for comprehensive variant detection in genotype-to-phenotype studies.

Black Box Machine Learning in Genomics and Drug Discovery

The Proliferation of Non-Interpretable Models

Machine learning algorithms have become indispensable tools for analyzing high-dimensional genomic data and predicting phenotypic outcomes. Deep learning approaches in particular have demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting drug resistance, cancer detection, and various genotype-phenotype associations [11]. However, these models often function as "black boxes" – they provide predictions without revealing the underlying logic or biological mechanisms behind their outputs.

In drug discovery, the black box effect presents a significant barrier to adoption. As Martin Akerman, Chief Technology Officer at Envisagenics, explained: "The Black Box Effect suggests that it's not always easy, relatable, or actionable to work with machine learning when there is an evident lack of understanding about the logic behind such predictions" [12]. This limitation is particularly problematic in pharmaceutical development, where understanding mechanism of action is crucial for both regulatory approval and scientific advancement.

Performance Versus Interpretability Trade-Offs

The fundamental tension in applying machine learning to biological problems lies in the trade-off between predictive performance and model interpretability. Complex models such as deep neural networks can capture non-linear relationships and complex interactions that elude simpler statistical approaches, but this capability comes at the cost of transparency.

Tools such as deepBreaks exemplify the ML approach to genotype-phenotype associations, using multiple machine learning algorithms to detect important positions in sequence data associated with phenotypic traits [11]. The software compares model performance and prioritizes positions based on the best-fit models, but the biological interpretation of these positions still requires additional experimentation and validation. Similarly, PhenoDP leverages deep learning for phenotype-based diagnosis of Mendelian diseases, employing a Ranker module that integrates multiple similarity measures to prioritize diseases based on Human Phenotype Ontology terms [13]. While these tools demonstrate impressive diagnostic accuracy, their decision-making processes can remain opaque to end-users.

Table 2: Comparison of Black Box vs. Glass Box Approaches in Genomics

| Feature | Black Box Approaches | Glass Box Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy | High for complex patterns | Variable; often slightly lower |

| Interpretability | Low | High |

| Mechanistic Insight | Limited | Directly provided |

| Biological Validation Required | Extensive | Minimal |

| Domain Expert Integration | Challenging | Straightforward |

| Examples | Deep neural networks, ensemble methods | Logistic regression, probabilistic models |

Methodologies for Mechanistic Understanding

Causal Inference Frameworks

Moving beyond correlation requires formal frameworks for causal inference. The counterfactual approach, based on ideas of intervention described in Judea Pearl's work on causality, aims to analyze observational data in a way that mimics randomized experiments [14]. This methodology uses tools such as marginal structural models with inverse probability weighting and causal diagrams (directed acyclic graphs) to estimate causal effects from observational data.

In epidemiology, these approaches have been applied to unravel complex relationships between socioeconomic status, health, and employment outcomes [14]. The same principles can be adapted to genetic studies to distinguish causal variants from merely correlated ones. Dynamic path analysis represents another method for estimating direct and indirect effects, particularly useful when time-to-event is the outcome [14]. These approaches explicitly model the pathways through which genetic variation influences phenotypic outcomes, thereby providing mechanistic insights rather than mere associations.

Explainable AI and Glass Box Methodologies

A promising alternative to black box approaches is the development of "glass box" or explainable AI (XAI) methods that prioritize visibility and interpretability. In drug discovery, glass box approaches emphasize probabilistic methods that provide guidelines about what chemical groups to include and avoid in future syntheses, quantifying relationships in probabilistic terms [15]. These methods demonstrate comparable predictive power to black box approaches while offering transparent decision-making processes.

Envisagenics has implemented this approach in their SpliceCore platform, which identifies drug targets in RNA splicing-related diseases. They achieve transparency by incorporating domain knowledge as a key component of the predictive engine, creating a feedback loop where prior understanding of targets and their functionalities improves model relatability [12]. As noted by their CTO, "It is preferable to sacrifice a little bit of predictive accuracy for transparency during digitisation because if we cannot articulate what the features are showing in the predictive model, it will be even more difficult to interpret them retroactively" [12].

Comprehensive Variant Integration

Methodologies that capture the full spectrum of genetic variation represent another approach to enhancing mechanistic understanding. The yeast telomere-to-telomere genome study exemplifies this approach, utilizing long-read sequencing strategies and pangenome approaches to enable high-resolution detection of structural variants at the population level [10]. This comprehensive variant mapping allows researchers to move beyond SNP-centric models and develop more complete models of genetic architecture.

The experimental protocol for this approach involves:

- Sample Preparation: 1,086 natural isolates sequenced using Oxford Nanopore technology (ONT) with average depth of 95× and N50 of 19.1 kb [10]

- Assembly Pipeline: Hybrid assembly pipeline to maximize contiguity and completeness, yielding chromosome-scale assemblies

- Variant Detection: Pairwise alignment of assemblies with reference genome to identify structural variants (>50 bp)

- Variant Classification: Categorization into presence-absence variations, copy-number variations, inversions, and translocations

- Association Testing: Integration with phenotypic data across 8,391 molecular and organismal traits

This methodology revealed 262,629 redundant structural variants across the 1,086 isolates, corresponding to 6,587 unique events, highlighting the extensive genomic diversity that had been previously overlooked in SNP-focused studies [10].

Experimental Protocols for Bridging the Divide

The deepBreaks Framework for Genotype-Phenotype Association

The deepBreaks software provides a generic approach to detect important positions in sequence data associated with phenotypic traits while maintaining interpretability [11]. The experimental protocol consists of three phases:

Phase 1: Preprocessing

- Input: Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) file and phenotypic metadata

- Missing value imputation and handling of ambiguous reads

- Removal of zero-entropy columns (non-informative positions)

- Clustering of correlated positions using DBSCAN algorithm

- Selection of representative features from each cluster

- Normalization using min-max normalization to mean 0 and scale 1

Phase 2: Modeling

- For continuous phenotypes: Adaboost, Decision Tree, Random Forest, and other regressors

- For categorical phenotypes: Multiple classifiers including ensemble methods

- Model comparison using k-fold cross-validation (default: tenfold)

- Performance metrics: Mean absolute error (regression) or F-score (classification)

Phase 3: Interpreting

- Feature importance calculation using the best-performing model

- Scaling of importance values between 0 and 1

- Assignment of importance values to features clustered together

- Output of prioritized positions based on their discriminative power

This approach addresses challenges such as noise components from sequencing, nonlinear genotype-phenotype associations, collinearity between input features, and high dimensionality of input data [11].

PhenoDP Diagnostic Platform for Mendelian Diseases

PhenoDP represents a comprehensive approach to phenotype-driven diagnosis that integrates multiple methodologies for enhanced interpretability [13]. The system consists of three modules:

Summarizer Module Protocol:

- Fine-tune Bio-Medical-3B-CoT model using HPO term definitions from OMIM and Orphanet databases

- Apply low-rank adaptation (LoRA) technology for efficient parameter adjustment

- Generate patient-centered clinical summaries from HPO terms

- Output structured clinical reports combining symptoms with probable diagnoses

Ranker Module Protocol:

- Compute similarity between patient HPO terms and disease HPO terms using three measures:

- Information content-based similarity (Jiang and Conrath method)

- Phi-correlation coefficient-based similarity

- Semantic similarity using cosine similarity in embedding space

- Combine similarity measures using ensemble learning

- Generate ranked list of potential Mendelian diseases

Recommender Module Protocol:

- Employ contrastive learning to identify missing HPO terms

- Suggest additional symptoms for differential diagnosis

- Validate suggestions against clinical databases

- Refine recommendations based on Ranker output

This protocol has demonstrated state-of-the-art diagnostic performance, consistently outperforming existing phenotype-based methods across both simulated and real-world datasets [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Mechanistic Studies

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application in Genotype-Phenotype Research |

|---|---|---|

| SpliceCore | Cloud-based, exon-centric AI/ML platform | Identifies splicing-derived drug targets; quantifies RNA splicing [12] |

| deepBreaks | Machine learning software for sequence analysis | Prioritizes important genomic positions associated with phenotypes [11] |

| PhenoDP | Deep learning-based diagnostic toolkit | Prioritizes Mendelian diseases using HPO terms; suggests additional symptoms [13] |

| BGData R Package | Suite for genomic analysis with big data | Enables handling of extremely large genomic datasets [9] |

| BGLR R Package | Bayesian generalized linear regression | Enables joint analysis from multiple cohorts without sharing individual data [9] |

| GenoTools | Python package for population genetics | Integrates ancestry estimation, quality control, and GWAS capabilities [9] |

| Oxford Nanopore Technology | Long-read sequencing platform | Enables telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies for structural variant detection [10] |

| Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | Standardized vocabulary of phenotypic abnormalities | Facilitates phenotype-driven analysis and diagnosis of Mendelian diseases [13] |

| Pentafluorophenol | Pentafluorophenol | High-Purity Reagent for Synthesis | Pentafluorophenol (PFP) is a key reagent for peptide coupling & material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Ibutamoren | Ibutamoren | High-Purity Growth Hormone Secretagogue | Ibutamoren (MK-677), a potent growth hormone secretagogue for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The distinction between statistical association and mechanistic understanding represents a fundamental challenge in genotype-to-phenotype research. While black box approaches offer powerful predictive capabilities, their inability to provide biological insights ultimately limits their utility for advancing fundamental knowledge and developing targeted interventions. The research community must continue to develop and adopt methodologies that balance predictive power with interpretability, leveraging comprehensive variant detection, causal inference frameworks, and explainable AI.

The future of genotype-phenotype research lies in approaches that seamlessly integrate statistical rigor with biological plausibility. By prioritizing mechanistic understanding alongside predictive accuracy, researchers can transform the black box of statistical association into the glass box of causal understanding, ultimately enabling more effective personalized medicine, drug development, and fundamental biological insight. As the field moves forward, the integration of multiple data types – from structural variants to molecular phenotypes – will be essential for developing complete models of genetic architecture that fulfill the promise of the genomic era.

The field of genotype-to-phenotype (G2P) prediction stands as a central challenge in modern biology, with profound implications for crop breeding, personalized medicine, and evolutionary studies [16]. Despite revolutionary advances in genome sequencing technologies that have generated vast amounts of genetic data, our ability to accurately predict phenotypic outcomes from genotypic information remains critically constrained. The core limitation lies not in the genomic data itself, but in the scarcity and complexity of high-quality, annotated phenotypic datasets required to train and validate predictive models [16] [17].

This technical guide examines the multifaceted nature of data scarcity in G2P research, quantifying the scale of the problem, analyzing its underlying causes, and presenting innovative computational and experimental frameworks designed to overcome these limitations. Within the broader context of G2P prediction challenges, the issue of phenotypic data scarcity represents a fundamental bottleneck that impedes the development of accurate, generalizable models capable of deciphering the complex relationships between genetic makeup and observable traits across diverse biological systems and environmental conditions [18] [17].

The Genotype-Phenotype Data Landscape

Quantifying the Data Imbalance

The disparity between the abundance of genomic data and the scarcity of high-quality phenotypic data creates a fundamental asymmetry in G2P research. The following table quantifies this imbalance across different biological scales and research domains.

Table 1: The Genotype-Phenotype Data Imbalance Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Genomic Data Scale | Phenotypic Data Limitations | Impact on Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Plants | Billions of genetic markers identified; Pangenomes for multiple species [16] [19] | High-quality phenotyping prohibitively expensive; Multi-environment trials scarce [16] [20] | ML models fail to capture G×E interactions; Limited transferability across environments [16] |

| Human Populations | 1.5 billion variants identified in UK Biobank WGS study [21] | Phenotypes often subjective, manually scored; Scarce molecular trait data [21] | Poor resolution for complex traits; Missing heritability problems persist [21] |

| Model Organisms (Yeast) | 1,086 near telomere-to-telomere genomes; 262,629 structural variants [10] | Comprehensive phenotyping for 8,391 traits required massive coordinated effort [10] | Structural variants poorly characterized without comprehensive phenotyping [10] |

Dimensions of Phenotypic Data Scarcity

The challenge of phenotypic data scarcity manifests across multiple dimensions, each presenting distinct methodological hurdles:

Volume and Comprehensiveness: Even in extensively studied model organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, capturing the full phenotypic landscape requires enormous systematic effort. The recent yeast phenotyping initiative measured 8,391 molecular and organismal traits across 1,086 isolates to create a sufficiently comprehensive dataset [10]. In clinical genetics, databases like NMPhenogen for neuromuscular disorders must aggregate phenotypes across 1,240 different conditions linked to 747 genes, highlighting the sheer scale of phenotypic diversity that must be captured [22].

Annotation Consistency: Inconsistent metadata annotation represents a critical barrier to data integration and model training. Plant phenotyping studies note that "inconsistent metadata annotation" substantially reduces the utility of aggregated datasets [16] [19]. This problem is particularly acute in medical genetics, where the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines provide standardization frameworks, but implementation varies significantly across institutions and platforms [22].

Temporal Resolution: Many phenotypes are dynamic, yet most datasets capture only single timepoints. Plant growth traits, disease progression in neuromuscular disorders, and developmental phenotypes all require longitudinal assessment to be meaningful, dramatically increasing data collection costs and complexity [16] [22].

Root Causes of Phenotypic Data Scarcity

Technical and Methodological Constraints

The acquisition of high-quality phenotypic data faces numerous technical barriers that limit dataset scale and quality:

Phenotyping Throughput Limitations: Traditional phenotyping methods for visual or morphological traits require labor-intensive manual assessment. In crop breeding, traits requiring "visual assessments or physical measurements" create significant bottlenecks [17]. Similarly, clinical diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders relies on "invasive procedures like muscle biopsy" and expert assessment, limiting throughput [22].

Multidimensional Phenotype Complexity: Comprehensive phenotyping requires capturing data at multiple biological levels. The PhyloG2P matrix framework emphasizes that "intermediate traits layered in between genotype and the phenotype of interest, including but not limited to transcriptional profiles, chromatin states, protein abundances, structures, modifications, metabolites, and physiological parameters" are essential for mechanistic understanding but enormously increase data acquisition challenges [23].

Standardization and Interoperability Gaps: Without community-wide standards, phenotypic data collected by different research groups cannot be effectively aggregated. Plant phenotyping studies note "inconsistent metadata annotation" as a major limitation [16], while clinical genetics faces challenges with "population-specific genetic databases" and variant interpretation standards [22].

Resource and Economic Factors

Beyond technical challenges, significant resource constraints impede the collection of comprehensive phenotypic data:

Cost Disparities: Genome sequencing costs have decreased dramatically, while high-quality phenotyping remains expensive and labor-intensive. In plant breeding, "phenotyping large cohorts of plants can be prohibitively expensive, restricting the number of samples" [16] [19]. This economic reality creates fundamental constraints on dataset balance.

Domain Expertise Requirements: Accurate phenotype annotation often requires specialized expertise that does not scale efficiently. Clinical phenotyping for neuromuscular disorders demands "medical geneticists and other health care professionals to provide quality medical genetic services" [22], creating workforce limitations.

Infrastructure Demands: Advanced phenotyping technologies such as unmanned aerial vehicles for crop monitoring [16] or specialized equipment for molecular phenotyping [10] represent substantial investments beyond the reach of many research groups.

Experimental Frameworks for Data-Efficient G2P Prediction

Innovative Experimental Designs

Several innovative experimental approaches address data scarcity challenges through strategic design:

- The Near Telomere-to-Telomere Yeast Genome Initiative: This project demonstrates how extreme completeness in genomic characterization can partially compensate for phenotypic data limitations. By generating 1,086 near-complete genomes with comprehensive structural variant mapping, researchers created a resource where "the inclusion of structural variants and small insertion–deletion mutations improved heritability estimates by an average of 14.3% compared with analyses based only on single-nucleotide polymorphisms" [10]. The experimental workflow for this approach is detailed below:

Diagram 1: High-Quality Genome Assembly Workflow

- Multi-Trait Phenotyping Strategies: Simultaneous measurement of multiple related phenotypes increases data efficiency by capturing pleiotropic effects and trait correlations. In yeast, coordinated measurement of "8,391 molecular and organismal traits" enabled detection of pleiotropy where "structural variants were more frequently associated with traits and exhibited greater pleiotropy than other variant types" [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for Data-Efficient G2P Studies

The following table details essential research reagents and computational tools that enable data-efficient G2P studies:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Data-Efficient G2P Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Function in Addressing Data Scarcity |

|---|---|---|

| Near Telomere-to-Telomere Assemblies | 1,086 S. cerevisiae isolates; 95× ONT coverage; median 1.06 contigs per chromosome [10] | Provides complete variant spectrum including structural variants that improve heritability estimates by 14.3% [10] |

| Pangenome References | Graph pangenome with 2.5 Mb non-reference sequence; 6,587 unique SVs [10] | Captures species-wide diversity beyond reference genome, improving association power for rare variants [10] |

| Denoising Autoencoder Framework | Two-tiered architecture; phenotype-phenotype encoder followed by genotype-phenotype mapping [18] | Enables data-efficient training by learning compressed phenotypic representations; robust to missing data [18] |

| Generative AI Phenotype Sequencer | AIPheno framework; unsupervised extraction from imaging data [21] | Creates quantitative digital phenotypes from images, bypassing manual annotation bottlenecks [21] |

| Diffusion Models for Morphology | G2PDiffusion; environment-enhanced DNA conditioner; dynamic alignment [17] | Generates visual phenotypes from genotypes, augmenting limited training data [17] |

Computational Strategies for Data Scarcity Mitigation

Data-Efficient Machine Learning Architectures

Novel computational frameworks specifically designed for data-limited biological contexts offer promising approaches to overcome phenotypic data scarcity:

G–P Atlas Neural Network Framework: This two-tiered denoising autoencoder architecture addresses data scarcity through improved data efficiency. The framework first learns a low-dimensional representation of phenotypes through denoising autoencoding, then maps genetic data to these representations. This approach "leads to a data-efficient training process" and demonstrates robustness to missing and corrupted data, which are common in biological datasets [18]. The architecture is particularly valuable because it can "capture nonlinear relationships among parameters even with minimal data" [18].

Generative AI for Digital Phenotyping: The AIPheno framework represents a paradigm shift in phenotyping through "high-throughput, unsupervised extraction of digital phenotypes from imaging data" [21]. By transforming imaging modalities into quantitative traits without manual intervention, this approach dramatically increases phenotyping throughput. Critically, it includes a generative module that "decodes AI-derived phenotypes by synthesizing variant-specific images to yield actionable biological insights" [21], addressing the interpretability challenges of unsupervised approaches.

Integration of Intermediate Traits

The PhyloG2P matrix framework proposes leveraging intermediate molecular traits to bridge the genotype-phenotype gap. This approach recognizes that "intermediate traits layered in between genotype and the phenotype of interest, including but not limited to transcriptional profiles, chromatin states, protein abundances, structures, modifications, metabolites, and physiological parameters" can provide crucial connecting information [23]. By explicitly modeling these intermediate layers, researchers can achieve "a deep, integrated, and predictive understanding of how genotypes drive phenotypic differences" [23] even when direct genotype-to-phenotype mapping is limited by data scarcity.

The following diagram illustrates how this integration of multi-scale data creates a more complete predictive framework:

Diagram 2: Multi-Scale Data Integration Framework

Cross-Species and Transfer Learning Approaches

Cross-species frameworks increase effective dataset sizes by leveraging evolutionary conservation. G2PDiffusion demonstrates this approach by using "images to represent morphological phenotypes across species" and "redefining phenotype prediction as conditional image generation" across multiple species [17]. This strategy "increases the data scale and diversity, ultimately improving the power of our models in diverse biological contexts" [17] by identifying conserved genetic patterns and pathways shared among species.

The integration of innovative experimental designs with data-efficient computational frameworks represents the most promising path forward for overcoming the challenges of phenotypic data scarcity in G2P prediction. Strategic priorities include:

Development of Community-Wide Standards: Widespread adoption of standardized phenotyping protocols and metadata annotation schemas is essential for data integration across research groups and species [16] [22].

Investment in Automated Phenotyping Technologies: Technologies that enable high-throughput, quantitative phenotyping—such as the AI-driven "phenotype sequencer" [21] and image-based phenotyping [17]—must be prioritized to address the fundamental throughput disparities between genotyping and phenotyping.

Advancement of Data-Efficient Algorithms: Computational frameworks specifically designed for data-limited contexts, such as the two-tiered denoising autoencoder approach of G–P Atlas [18], will be essential for maximizing insights from limited phenotypic data.

The critical bottleneck in genotype-to-phenotype prediction has clearly shifted from genomic data acquisition to phenotypic data scarcity and complexity. By addressing this challenge through integrated experimental and computational strategies that enhance data quality, completeness, and utility, the research community can unlock the full potential of G2P prediction to advance fundamental biological understanding and enable transformative applications across medicine, agriculture, and conservation biology.

Methodological Revolution: Machine Learning and Integrative Frameworks for Enhanced Prediction

A fundamental hurdle in biomedical research and drug development lies in the poor translatability of preclinical findings to human outcomes. This translational gap arises primarily from biological differences between model organisms and humans, leading to high clinical trial attrition rates and post-marketing drug withdrawals. Existing toxicity prediction methods have predominantly relied on chemical properties, typically overlooking these critical inter-species differences [24]. The genotype to phenotype prediction challenge represents a core problem in translational medicine, where understanding how genetic information manifests as observable traits across different species is paramount. This whitepaper presents a machine learning framework that incorporates Genotype-Phenotype Differences (GPD) between preclinical models and humans to significantly improve the prediction of human drug toxicity.

Theoretical Foundation: Genotype-Phenotype Relationships

Defining Genotype and Phenotype

The terms genotype and phenotype represent fundamental concepts in genomic science. A genotype constitutes the entire set of genes that an organism carries—its unique DNA sequence that is hereditary material passed from one generation to the next [25]. In contrast, a phenotype encompasses all observable characteristics of an organism, influenced both by its genotype and its environmental interactions [25]. While the genotype is the genetic blueprint, the phenotype represents how that blueprint is expressed in reality, which can depend on factors ranging from cellular environment to dietary influences.

The Cross-Species Disconnect

The critical challenge in translational research emerges from discordant genotype-phenotype relationships across species. A genetic variant or pharmaceutical intervention that produces a particular phenotype in a model organism (e.g., mouse or cell line) may yield a dramatically different phenotypic outcome in humans due to evolutionary divergence in gene function, expression patterns, and biological networks [24]. This discordance is particularly problematic for drug development, where toxicity phenotypes observed in humans often fail to manifest in preclinical models, leading to unexpected adverse events in clinical trials.

The GPD Framework: Methodology and Implementation

Core Conceptual Approach

The GPD-based prediction framework addresses the cross-species translatability gap by systematically quantifying differences in how genotypes manifest as phenotypes between preclinical models and humans. Rather than relying solely on chemical structure-based predictions, this approach incorporates fundamental biological differences through three specific biological contexts [24]:

- Gene Essentiality Differences: Variations in how critical specific genes are for survival and function between species

- Tissue Expression Profiles: Divergent gene expression patterns across homologous tissues

- Network Connectivity: Differences in protein-protein interaction networks and biological pathway architectures

Experimental Design and Data Curation

The development and validation of the GPD framework followed a rigorous experimental methodology:

Dataset Composition: The model was trained and validated using a comprehensive dataset of 434 risky drugs (associated with severe adverse events in clinical trials or post-marketing surveillance) and 790 approved drugs with acceptable safety profiles [24]. This balanced dataset ensured robust model training while representing real-world clinical risk distributions.

Feature Engineering: GPD features were quantitatively assessed for each drug target across the three biological contexts (gene essentiality, tissue expression, network connectivity). These biological features were integrated with conventional chemical structure descriptors to create a multidimensional feature space.

Machine Learning Framework: A Random Forest algorithm was implemented to integrate GPD features with chemical properties. This ensemble learning approach was selected for its ability to handle high-dimensional data, capture complex non-linear relationships, and provide feature importance metrics [24].

GPD Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive experimental workflow for implementing the GPD framework in drug toxicity assessment:

Performance Benchmarks and Validation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The GPD framework was rigorously benchmarked against state-of-the-art toxicity prediction methods using independent datasets and chronological validation to assess its real-world predictive capabilities [24].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Toxicity Prediction Models

| Model Type | AUROC | AUPRC | Key Strengths | Major Toxicity Types Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPD-Based Model (Random Forest) | 0.75 | 0.63 | Superior cross-species translatability; Biological interpretability | Neurotoxicity, Cardiovascular toxicity |

| Chemical Structure-Based Baseline | 0.50 | 0.35 | Standard industry approach; Rapid prediction | Limited to chemical similarity |

| Enhanced GPD Model (with chemical features) | 0.75+ | 0.63+ | Combines biological relevance with chemical properties | Comprehensive coverage including previously challenging toxicity types |

Validation on Specific Toxicity Endpoints

The GPD framework demonstrated particular efficacy in predicting complex toxicity phenotypes that have traditionally challenged conventional models:

- Neurotoxicity: Improved identification of compounds causing adverse neurological effects, a major cause of clinical trial failures

- Cardiovascular Toxicity: Enhanced prediction of drug-induced cardiovascular complications, which often emerge only in human populations

- Organ-Specific Toxicity: Better translatability for tissue-specific adverse events due to incorporation of tissue expression differences

The model's practical utility was confirmed through its ability to anticipate future drug withdrawals in real-world settings, demonstrating significant improvement over existing methods [24].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of the GPD framework requires specific research reagents and computational tools that enable robust genotype-phenotype analyses across species.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GPD Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in GPD Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Tools | rhAmp SNP Genotyping System | Accurate determination of genetic variants | Preclinical model characterization; Human genotype-phenotype association studies |

| Sequencing Technologies | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Comprehensive genome and transcriptome profiling | Whole-genome sequencing for genotype determination; Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping |

| Computational Packages | GenoTools (Python) | Streamlines population genetics research | Ancestry estimation; Quality control; Genome-wide association studies [9] |

| Statistical Software | BGLR R-package | Bayesian analysis of biobank-size data | Efficient handling of large-scale genotype-phenotype datasets; Meta-analysis of multiple cohorts [9] |

| Data Integration Platforms | BGData R-package | Management and analysis of large genomic datasets | Handling extremely large genotype-phenotype datasets efficiently [9] |

Analytical Framework for GPD Assessment

The GPD analytical process involves multiple computational steps to transform raw biological data into meaningful cross-species difference metrics that can predict human drug toxicity.

Implementation Protocol for GPD Analysis

Step-by-Step Experimental Methodology

Implementing the GPD framework requires a systematic approach to data collection, processing, and analysis:

Biological Data Acquisition

- Collect gene essentiality data from CRISPR screens in human and model organism cell lines

- Acquire tissue-specific expression profiles from RNA-seq datasets for homologous tissues across species

- Obtain protein-protein interaction networks from curated databases for both human and model organisms

GPD Metric Calculation

- Compute quantitative difference scores for each biological context using appropriate distance metrics

- Normalize difference scores to account for varying scales across data types

- Integrate multiple difference metrics into composite GPD features for each drug target

Machine Learning Integration

- Concatenate GPD features with chemical descriptors into a unified feature matrix

- Train Random Forest classifier using stratified k-fold cross-validation

- Optimize hyperparameters through grid search with performance evaluation on hold-out sets

Model Validation

- Assess performance using independent validation sets not seen during training

- Conduct chronological validation to simulate real-world deployment scenarios

- Perform ablation studies to quantify the specific contribution of GPD features to predictive accuracy

Interpretation Guidelines

The GPD framework generates interpretable biological insights alongside predictive outputs:

- Feature Importance: The relative contribution of different GPD contexts (essentiality, expression, networking) indicates which biological mechanisms drive cross-species differences for specific compounds

- Risk Stratification: Compounds can be categorized into risk tiers based on both the magnitude of GPD signals and predicted toxicity probabilities

- Mechanistic Hypotheses: High GPD features for specific targets generate testable hypotheses about species-specific biological mechanisms that could explain differential toxicity

The incorporation of Genotype-Phenotype Differences between preclinical models and humans represents a biologically grounded strategy for improving drug toxicity prediction. By addressing the fundamental challenge of cross-species translatability, the GPD framework enables earlier identification of high-risk compounds during drug development, with potential to reduce development costs, improve patient safety, and increase therapeutic approval success rates [24]. Future advancements will likely focus on refining GPD metrics through single-cell resolution data, incorporating additional biological contexts such as epigenetic regulation, and expanding to complex disease models beyond toxicity prediction. As genomic technologies continue to evolve and multi-species datasets grow more comprehensive, GPD-based approaches will play an increasingly critical role in bridging the species gap and realizing the promise of precision medicine.

The challenge of predicting complex phenotypic traits from genotypic data represents a core problem in modern computational biology, with profound implications for drug development, personalized medicine, and functional genomics. This prediction task is inherently complex, involving high-dimensional data, non-linear relationships, and significant noise components [11]. Researchers now leverage advanced machine learning algorithms to decipher these intricate genotype-phenotype associations.

Among the various algorithmic approaches, tree-based models (like Random Forest), boosting methods (such as XGBoost), and deep learning architectures have emerged as leading contenders. Each offers distinct mechanistic advantages for handling the specific challenges posed by biological data. Understanding their relative performance characteristics, optimal application domains, and implementation requirements is crucial for advancing research in this field.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these algorithmic families within the context of genotype-phenotype prediction. We synthesize recent benchmark studies, detail experimental methodologies, and provide practical resources to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate modeling strategies for their specific challenges.

Performance Benchmarking in Genotype-Phenotype Prediction

Different algorithmic approaches exhibit distinct performance characteristics across various data types and problem contexts in biological research. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies comparing tree-based models, boosting methods, and deep learning architectures.

Table 1: Performance comparison of machine learning models across different data types and applications

| Application Domain | Best Performing Model(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Tabular Data | Tree-Based Models (Random Forest, XGBoost) | 85-95% normalized accuracy (classification), 90-95% R² (regression) | Outperformed deep learning models (60-80% accuracy, <80% R²) | [26] |

| Drug Toxicity Prediction | Random Forest (with GPD features) | AUROC: 0.75, AUPRC: 0.63 | Surpassed chemical property-based models (AUROC: 0.50, AUPRC: 0.35) | [27] [28] |

| Vehicle Flow Prediction | XGBoost | Lower MAE and MSE | Outperformed RNN-LSTM, SVM, and Random Forest | [29] |

| High-Dimensional Tabular Data | QCML (Quantum-Inspired) | 86.2% accuracy (1000 features) | Superior to Random Forest (27.4%) and Gradient Boosted Trees | [30] |

Beyond these specific applications, research indicates that tree-based models generally demonstrate superior performance on structured, tabular data, which is common in genotype-phenotype studies [26]. The deepBreaks framework, designed specifically for identifying genotype-phenotype associations from sequence data, employs a multi-model comparison approach, ultimately using the best-performing model to identify the most discriminative sequence positions [11].

Experimental Protocols for Genotype-Phenotype Prediction

The deepBreaks Framework Workflow

The deepBreaks software provides a generalized, open-source pipeline for identifying important genomic positions associated with phenotypic traits. Its workflow consists of three main phases: preprocessing, modeling, and interpretation [11].

Figure 1: The deepBreaks workflow for identifying genotype-phenotype associations from multiple sequence alignments (MSA).

Phase 1: Data Preprocessing

- Input Data: The pipeline requires a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) file containing n sequences of length m, and a corresponding metadata file with phenotypic measurements (continuous, categorical, or binary) for each sequence [11].

- Processing Steps:

- Imputation: Handles missing values and ambiguous reads.

- Filtering: Drops positions (columns) with zero entropy that carry no information.

- Clustering: Uses the DBSCAN algorithm to identify and cluster highly correlated features. The feature closest to the center of each cluster is selected as a representative to mitigate collinearity.

- Normalization: Applies min-max normalization to the training data [11].

Phase 2: Modeling

- Model Training: Multiple machine learning models are trained on the preprocessed data. The specific models depend on the nature of the phenotype (a set for regression, another for classification) [11].

- Model Selection: Models are evaluated using a default tenfold cross-validation scheme. The model with the best average cross-validation score (e.g., Mean Absolute Error for regression, F-score for classification) is selected as the top model [11].

Phase 3: Interpretation

- Feature Importance: The selected top model is used to extract importance scores for each sequence position (feature). These scores are scaled between 0 and 1.

- Position Prioritization: The positions are ranked based on their importance scores. For features that were originally clustered, the same importance value is assigned to all members of the cluster. This final list represents the genomic positions most discriminative for the phenotype under study [11].

Genotype-Phenotype Difference (GPD) Framework for Drug Toxicity

A novel machine learning framework incorporating Genotype-Phenotype Differences (GPD) has been developed to improve the prediction of human drug toxicity by accounting for biological differences between preclinical models and humans [27] [28].

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational tools for GPD-based toxicity prediction

| Reagent/Solution | Type | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Toxicity Profiles | Dataset | Ground truth data from clinical trials (ClinTox) and post-marketing surveillance (e.g., ChEMBL) [27]. |

| STITCH Database | Database | Provides drug-target interactions and maps chemical identifiers (e.g., ChEMBL ID to STITCH ID) [27]. |

| RDKit Cheminformatics Toolkit | Software | Generates chemical fingerprints (e.g., MACCS, ECFP4) from SMILES strings for chemical similarity analysis [27]. |

| GPD Features | Computed Features | Quantifies inter-species differences in gene essentiality, tissue expression, and network connectivity [27] [28]. |

| Random Forest Classifier | Algorithm | Integrates chemical and GPD features for final toxicity risk prediction [27]. |

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for GPD-based drug toxicity prediction.

Experimental Workflow:

Data Curation:

- Toxic Drugs: Compile a set of "risky" drugs from those that failed clinical trials due to safety issues or were withdrawn from the market/post-market warnings. Sources include ClinTox and ChEMBL [27].

- Safe Drugs: Compile a set of approved drugs with no reported severe adverse events (excluding anticancer drugs due to different toxicity tolerance) [27].

- Preprocessing: Remove duplicate drugs with analogous chemical structures using Tanimoto similarity coefficients to minimize bias [27].

GPD Feature Engineering: For each drug's target gene, compute differences between preclinical models (e.g., cell lines, mice) and humans across three biological contexts [27] [28]:

- Gene Essentiality: Difference in the gene's impact on survival.

- Tissue Specificity: Difference in tissue expression profiles.

- Network Connectivity: Difference in the gene's connectivity within biological networks.

Model Training and Validation:

- Integration: A Random Forest classifier is trained on the integrated feature set (GPD features + traditional chemical descriptors) [27].

- Validation: Model robustness is assessed using independent datasets and chronological validation, where the model is trained on data up to a specific year and tested on its ability to predict drugs withdrawn after that year [27] [28].

Technical Underpinnings and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Strengths and Weaknesses

The performance disparities between algorithmic families stem from their fundamental operational principles.

Tree-Based Models (Random Forest, XGBoost):

- Handling of Irregular Patterns: Decision trees naturally partition the feature space using axis-aligned splits, allowing them to capture sharp, irregular decision boundaries common in tabular data without requiring extensive tuning [26].

- Robustness to Uninformative Features: Tree-based models use metrics like Information Gain and Gini impurity to select the most informative features at each split, effectively ignoring noisy or irrelevant data. Research shows they suffer minimal performance degradation when uninformative features are added, unlike neural networks [26].

- Lack of Rotation Invariance: Unlike neural networks, tree models are not rotation-invariant. This is advantageous for tabular data where features have specific, independent semantic meanings (e.g., "age" and "income"), as rotating this data destroys these meaningful axes [26].

Deep Learning Models (RNN-LSTM, MLPs):

- Inductive Bias for Smoothness: Neural networks rely on gradient descent and differentiable activation functions, which creates an inherent bias towards learning smooth, continuous solutions. This can be a disadvantage for learning the jagged, discontinuous patterns often found in structured tabular data [29] [26].

- Feature Dilution: In neural networks, all input features are mixed and transformed through successive layers. This can dilute the signal from strongly predictive individual features with noise from less informative ones, unless the network explicitly learns to ignore them [26].

- The Curse of Dimensionality: The number of branches in a decision tree grows exponentially with the number of features, which can lead to poor generalization on high-dimensional data with limited samples. While ensemble methods like Random Forest mitigate this, the fundamental challenge remains [30].

The Dimensionality Challenge

The "curse of dimensionality" presents a significant challenge in genotype-phenotype prediction, where the number of features (e.g., SNPs, genomic positions) can vastly exceed the number of samples. A benchmark study on high-dimensional synthetic tabular data reveals critical scaling laws [30].

- Tree-Based Models: The performance of Decision Trees and Random Forests degrades exponentially as the number of features increases, with accuracy approaching random guessing at high dimensions (e.g., ~1000 features). While Gradient Boosted Trees (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) show better mitigation, they still exhibit exponential performance decay [30].

- Alternative Approaches (QCML): In contrast, models with linear parameter scaling, such as the quantum-inspired QCML, demonstrate only linear performance degradation with increasing dimensionality. This different scaling law can result in dramatically higher accuracy (e.g., 68% vs. 24% for CatBoost) on very high-dimensional problems (e.g., 20,000 features) [30].

This underscores that no single algorithm is universally superior. The optimal choice depends on the specific data characteristics, including dimensionality, sample size, and the nature of the underlying patterns.

The algorithmic showdown in genotype-phenotype prediction reveals a nuanced landscape. For many standard tabular data problems, including those with highly stationary time series or structured features, tree-based models like XGBoost and Random Forest often provide superior accuracy, robustness, and interpretability [29] [26]. This is evidenced by their successful application in domains from traffic forecasting to drug toxicity prediction [29] [27].

However, deep learning architectures remain a powerful tool for specific data types and problems. The key to success lies in matching the algorithm's inductive biases to the problem structure. Furthermore, emerging approaches that break traditional scaling laws, like QCML, show promise for overcoming the curse of dimensionality in ultra-high-feature scenarios [30].

For researchers embarking on genotype-phenotype studies, a pragmatic approach is recommended: leverage flexible frameworks like deepBreaks [11] that systematically compare multiple models, prioritize biological feature engineering (e.g., GPD features [27]), and always validate model performance rigorously using domain-specific metrics and validation schemes.