Optimizing Genomic Prediction: A Practical Guide to Parameter Tuning for Enhanced Accuracy and Efficiency

This article provides a comprehensive guide to parameter tuning for genomic prediction models, a critical process for enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of breeding values in biomedical and agricultural research.

Optimizing Genomic Prediction: A Practical Guide to Parameter Tuning for Enhanced Accuracy and Efficiency

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to parameter tuning for genomic prediction models, a critical process for enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of breeding values in biomedical and agricultural research. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, advanced methodological applications, strategic optimization techniques for troubleshooting common issues, and robust validation frameworks for model comparison. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource offers actionable strategies to navigate the complexities of model configuration, from selecting core algorithms to integrating multi-omics data, ultimately empowering scientists to build more reliable and powerful predictive models.

Core Principles and Key Parameters in Genomic Prediction

Defining Genomic Prediction and the Critical Role of Parameter Tuning

Defining Genomic Prediction

What is Genomic Prediction? Genomic Prediction (GP) is a methodology that uses genome-wide molecular markers to predict the additive genetic value, or breeding value, of an individual for a particular trait [1]. The core principle is that variation in complex traits results from contributions from many loci of small effect [1]. By using all available markers simultaneously without applying significance thresholds, GP sums these small additive genetic effects to estimate the total genetic merit of an individual, even for traits not yet observed [1].

What are its Primary Goals and Applications? The primary goal is to accelerate genetic improvement in plant and animal breeding by enabling selection of superior parents earlier in the lifecycle, thereby shortening breeding cycles and reducing costs [2] [1] [3]. In evolutionary genetics, GP models can predict the genetic value of missing individuals, understand microevolution of breeding values, or select individuals for conservation purposes [1]. More recently, its application has expanded to predict the performance of specific parental crosses, optimizing selection further [3].

Main Methodological Categories and Their Parameters

Genomic prediction methods can be divided into three main categories, each with distinct underlying assumptions and tuning parameters [2].

| Category | Description | Key Methods | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parametric | Assumes marker effects follow specific prior distributions (e.g., normal distribution). | GBLUP, BayesA, BayesB, BayesC, Bayesian LASSO (BL), Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR) [2] [1]. | Prior distribution variances, shrinkage parameters [1]. |

| Semi-Parametric | Uses kernel functions to model complex, non-linear relationships. | Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces (RKHS) [2] [4]. | Kernel type (e.g., Linear, Gaussian), kernel bandwidth/parameters [4]. |

| Non-Parametric | Makes fewer assumptions about the underlying distribution of marker effects; often machine learning-based. | Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gradient Boosting (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) [2]. | Number of trees/tree depth, learning rate, number of boosting rounds, subsampling ratios. |

Benchmarking Performance and the Impact of Tuning

The predictive performance of different methods varies significantly based on the species, trait, and genetic architecture. Systematic benchmarking is essential for objective evaluation [2].

Comparative Performance of Different Methods A benchmarking study on diverse species revealed the following performance and computational characteristics [2]:

| Model Type | Example Methods | Mean Predictive Accuracy (r) | Relative Computational Speed | Relative RAM Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parametric | Bayesian Models | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| Non-Parametric | Random Forest | +0.014 | ~10x faster | ~30% lower |

| Non-Parametric | LightGBM | +0.021 | ~10x faster | ~30% lower |

| Non-Parametric | XGBoost | +0.025 | ~10x faster | ~30% lower |

Note: Predictive accuracy gains are relative to Bayesian models. Computational advantages do not account for hyperparameter tuning costs [2].

Choosing the Right Model and Tuning Strategy The optimal model depends on the genetic architecture of the trait:

- Parametric models like GBLUP/ridge regression are often accurate and fast for traits where a normal distribution of marker effects is a reasonable approximation, which is common in breeding populations with extensive linkage disequilibrium [1].

- Variable selection models (e.g., BayesB, LASSO) can be superior when individuals are less related and populations are polymorphic at some large-effect loci, as their priors allow some marker effects to be estimated as zero [1].

- Non-parametric/Machine Learning models show modest but significant gains in accuracy and major computational advantages for model fitting, though they require careful hyperparameter tuning [2].

- Kernel Methods (e.g., RKHS) are particularly powerful for capturing complex non-linear patterns and epistatic interactions that linear models might miss [4]. Tuning the kernel function and its parameters (e.g., the bandwidth in a Gaussian kernel) is critical for performance [4].

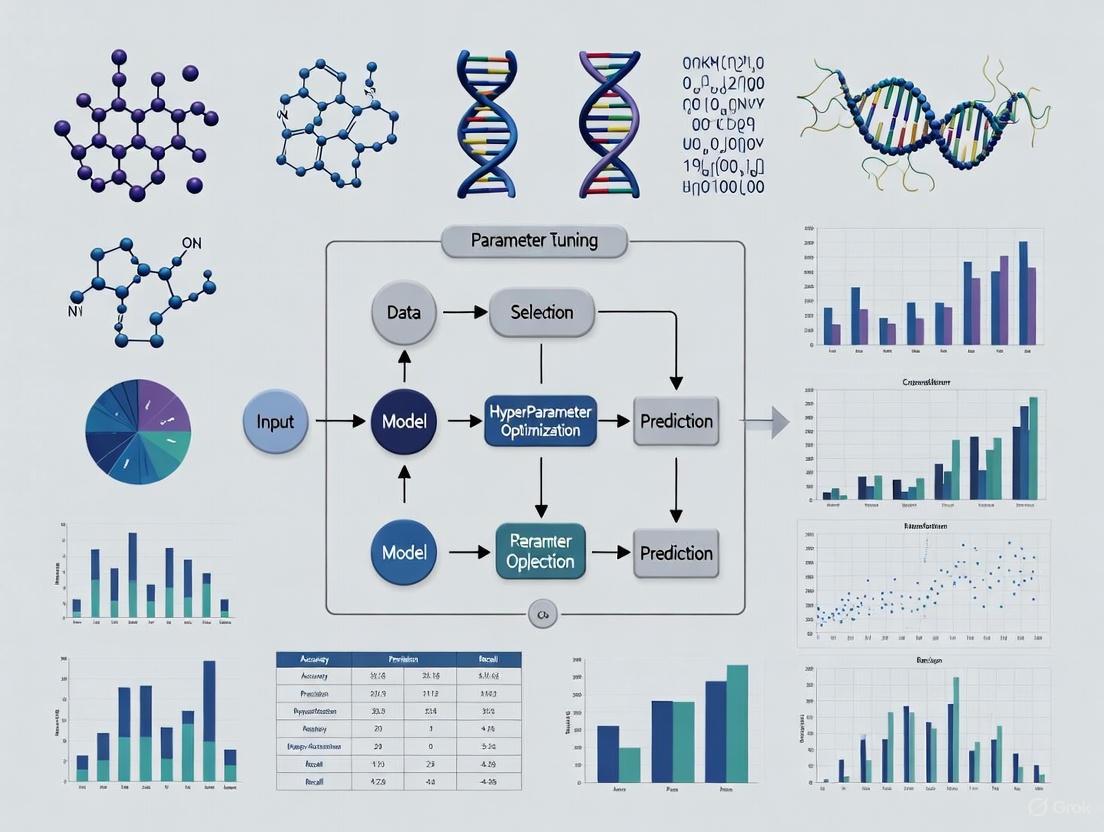

A Workflow for Genomic Prediction and Parameter Tuning

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for developing a genomic prediction model, highlighting the iterative process of parameter tuning.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key resources and tools used in modern genomic prediction research.

| Resource/Tool | Function in Genomic Prediction Research |

|---|---|

| EasyGeSe [2] | A curated collection of datasets from multiple species for standardized benchmarking of genomic prediction methods. |

| GPCP Tool [3] | An R package and BreedBase resource for predicting cross-performance using additive and dominance effects. |

| BreedBase [3] | An integrated platform for managing breeding program data, which hosts tools like GPCP. |

| sommer R Package [3] [5] | An R package used for fitting mixed models, including those for genomic prediction with complex variance-covariance structures. |

| AlphaSimR [3] | An R package for simulating breeding programs and genomic data, used to test methods and predict outcomes. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: Why is parameter tuning so critical in genomic prediction? Parameter tuning is essential because the predictive performance of a model is highly sensitive to its hyperparameters. For instance, in machine learning models like gradient boosting, the learning rate and tree depth control the model's complexity and its ability to learn from data without overfitting. In kernel methods like RKHS, the kernel bandwidth determines the smoothness of the function mapping genotypes to phenotypes [4]. Inappropriate parameter values can lead to underfitting (failing to capture important patterns) or overfitting (modeling noise in the training data), both of which result in poor predictive accuracy on new, unseen genotypes.

Q2: My genomic prediction model is overfitting. How can I address this? Overfitting typically occurs when a model is too complex for the amount of data available.

- Increase Regularization: Most methods have regularization parameters. For parametric Bayesian models, this is controlled by the prior variance; for machine learning models like XGBoost, parameters like

gamma,lambda, andalphapenalize complexity. For kernel methods, a regularization parameter balances fit and smoothness [4]. - Reduce Model Complexity: Simplify your model by reducing the number of parameters (e.g., shallower trees in random forest, fewer components in a model).

- Gather More Data: If possible, increase the size of your training population.

- Use Cross-Validation: Rigorously use cross-validation to evaluate the true predictive performance and guide your tuning process, ensuring your model generalizes beyond the training set [1].

Q3: What is the practical impact of choosing a non-linear kernel over a linear one? A linear kernel assumes a linear relationship between genotypes and the phenotype. In contrast, non-linear kernels (e.g., Gaussian, polynomial) can capture more complex patterns, including certain types of epistatic (gene-gene interaction) effects [4]. The practical impact is that for traits with substantial non-additive genetic variance, a well-tuned non-linear kernel can provide higher prediction accuracy. However, this comes at the cost of increased computational complexity and the need to tune the additional kernel parameter (e.g., bandwidth) [4].

Q4: I'm getting an error with the predict.mmer function in the sommer R package. What should I do?

This is a known issue that users have encountered. The package developer has noted that the predict function for mmer objects can be unstable and has recommended two potential solutions [5]:

- Use the

mmec()function: Consider refitting your model using themmec()function instead ofmmer, and then use the correspondingpredict.mmec()function, which is more robust. - Use

fitted.mmeras a workaround: As an interim solution, you can usefitted.mmer(your_model)$dataWithFittedto obtain fitted values [5]. The developer is working on unifying the two functions in a future release.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the fundamental differences between GBLUP, Bayesian, and Machine Learning models in genomic prediction?

The core difference lies in how they handle marker effects and genetic architecture.

- GBLUP: Uses a genomic relationship matrix (G-matrix) to model the genetic similarity between individuals, implicitly assuming all markers contribute equally to the trait (infinitesimal model) [6] [7].

- Bayesian Methods: Assume each marker can have its own effect, with specific prior distributions (e.g., BayesA, BayesB, BayesC) that allow for variable selection and unequal marker variances, better suited for traits influenced by a few major genes [8] [9].

- Machine Learning (ML): Non-parametric models like Deep Learning or Random Forest that flexibly learn complex, non-linear patterns and interactions from the data without strong pre-specified assumptions about the underlying genetic architecture [7] [10].

2. My GBLUP model performance is plateauing. What are the first parameters I should investigate tuning?

First, examine if the assumption of equal marker variance is limiting your predictions. Advanced tuning strategies include:

- Constructing a Weighted GBLUP (wGBLUP): Instead of a standard G-matrix, weight markers by their estimated effects (e.g., from an initial Bayesian analysis) to create a trait-specific relationship matrix. This can account for the unequal genetic variance of different genomic regions [6].

- Incorporating Non-Additive Effects: Build additional relationship matrices for dominance and epistasis (e.g., via Hadamard products of the additive G-matrix) and include them in your model to capture non-linear genetic effects [11] [12].

3. When should I choose a complex Deep Learning model over a conventional method like GBLUP?

Deep Learning excels when you have a large training population (e.g., >10,000 individuals) and suspect the trait is governed by complex, non-linear interactions (epistasis) that linear models cannot capture [11] [10]. For smaller datasets or traits with a predominantly additive genetic architecture, conventional methods like GBLUP or Bayesian models often provide comparable or superior performance with less computational cost and complexity [7] [10]. A hybrid approach, like the deepGBLUP framework, which integrates deep learning networks to estimate initial genomic values and a GBLUP framework to leverage genomic relationships, can sometimes offer the best of both worlds [11].

4. What are the common pitfalls when applying Machine Learning to genomic data, and how can I avoid them?

Common pitfalls and their solutions are summarized in the table below.

Table: Common Machine Learning Pitfalls in Genomics and Mitigation Strategies

| Pitfall | Description | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Distributional Differences | Training and prediction sets come from different biological contexts or technical batches (e.g., different breeds, sequencing platforms) [13]. | Use visualization and statistical tests to detect differences. Apply batch correction methods or adversarial learning [13]. |

| Dependent Examples | Individuals in the dataset are genetically related, violating the assumption of independent samples [13]. | Use group k-fold cross-validation where related individuals are kept in the same fold. Employ mixed-effects models that account for covariance [13]. |

| Confounding | An unmeasured variable creates spurious associations between genotypes and phenotypes (e.g., population structure) [13]. | Include principal components of the genomic data as covariates in the model to capture and adjust for underlying structure [13]. |

| Leaky Preprocessing | Information from the test set leaks into the training set during data normalization or feature selection, causing over-optimistic performance [13]. | Perform all data transformations, including feature selection and scaling, within the training loop of the cross-validation, completely independent of the test set [13]. |

5. How can I systematically evaluate and compare the performance of different genomic prediction models?

A robust evaluation requires a standardized machine learning workflow:

- Cross-Validation (CV): Use k-fold CV to repeatedly split data into training and testing sets, ensuring the performance metric is an average over multiple partitions. For genomic data, use group k-fold CV to keep related individuals together and prevent overestimation [14].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: For each model, perform an inner cross-validation loop on the training set to find the optimal hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate for DL, shrinkage parameters for Bayesian models) [14].

- Performance Metrics: Use appropriate metrics for your trait type. For continuous traits, use Mean Square Error (MSE) or prediction accuracy (correlation between predicted and observed values). For binary traits, use area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) [14] [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting GBLUP and Related Mixed Models

Problem: Low prediction accuracy, potentially due to oversimplified model assumptions.

Table: GBLUP Experimental Parameters and Tuning Guidance

| Parameter / Component | Description | Tuning Guidance & Common Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Relationship Matrix (G) | A matrix capturing the genetic similarity between individuals based on their markers [6]. | Standardize genotypes to a mean of 0 and variance of 1 before calculating G. The vanilla G assumes all markers have equal variance. |

| Weighted GBLUP (wGBLUP) | An advanced G-matrix where SNPs are weighted by their estimated effects to reflect unequal variance [6]. | Protocol: 1) Run a Bayesian method (e.g., BayesA) on the training data. 2) Use the posterior variances of SNP effects as weights. 3) Construct a new, weighted G-matrix. 4) Refit the GBLUP model. This often outperforms standard GBLUP when trait architecture deviates from the infinitesimal model [6]. |

| Non-Additive Effects | Genetic effects not explained by the simple sum of allele effects, such as dominance and epistasis [11]. | Protocol: Construct separate relationship matrices for dominance (GD) and epistasis (GE). For epistasis, GE is often computed as the Hadamard product of the additive G-matrix with itself [11] [12]. Include these as random effects in a multi-kernel model: y = μ + Z<sub>a</sub>u<sub>a</sub> + Z<sub>d</sub>u<sub>d</sub> + Z<sub>e</sub>u<sub>e</sub> + e. |

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for developing an advanced GBLUP model.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Bayesian Models

Problem: Model is computationally intensive, slow to converge, or results are sensitive to prior choices.

Table: Bayesian Model Families and Tuning Strategies

| Model / Prior | Description | Tuning Focus & Computational Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BayesA | Each SNP has its own effect, sampled from a Student's t-distribution. Shrinks small effects but allows large ones [9]. | Tuning the degrees of freedom and scale parameters of the t-distribution is crucial. Computationally intensive via MCMC. |

| BayesB | A variable selection model: a proportion (π) of SNPs have zero effect; the rest have effects from a t-distribution [8] [9]. | The π parameter (proportion of SNPs with zero effect) is critical. It can be pre-specified or estimated from the data (BayesBπ). MCMC sampling can be slow. |

| BayesC & BayesCπ | Similar to BayesB, but non-zero effects are sampled from a single normal distribution [8]. | Simpler than BayesB. In BayesCπ, the proportion π is estimated. Often offers a good balance between flexibility and computational stability. |

| Bayesian LASSO (BL) | Uses a Laplace (double-exponential) prior to strongly shrink small effects to zero [9]. | The regularization parameter (λ) controls the level of shrinkage. It can be assigned a hyperprior to be estimated from the data. |

Actionable Protocol: Implementing an Efficient Bayesian Analysis

- Choice of Prior: Start with BayesCÏ€ as a default for its balance of variable selection and computational efficiency. Use more complex priors (e.g., BayesB) if you have strong evidence of a trait controlled by very few QTL [8].

- Computational Speed-up: For large datasets, consider fast Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithms (e.g., fastBayesA) that approximate the posterior mode instead of full MCMC sampling, significantly reducing computation time [8] [9].

- Convergence Diagnosis: When using MCMC, always run multiple chains with different starting values. Use diagnostics like the Gelman-Rubin statistic to assess convergence. Visually inspect trace plots to ensure the chain is mixing well and is not stuck [9].

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Machine Learning Models

Problem: A complex ML model (e.g., Deep Learning) is underperforming a simple linear model.

Actionable Protocol: A Standardized ML Workflow for Genomics Adhering to a rigorous workflow is key to successfully applying ML in genomics.

- Data Preprocessing and Splitting: Standardize genotype data. Use Group K-Fold Cross-Validation to split data, ensuring that genetically related individuals are not split across training and test sets, which prevents data leakage and over-optimistic performance [13] [14].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Conduct an inner cross-validation loop within the training set to find the optimal model settings. For example:

- Model Training and Evaluation: Train the model on the entire training set with the best hyperparameters. Make final predictions on the untouched test set and calculate your performance metrics (e.g., MSE, accuracy). Repeat this process for all folds in the outer loop to get a robust estimate of model performance [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Genomic Prediction

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| PLINK | Software | A core tool for genome association analysis. Used for quality control (QC) of SNP data, filtering by minor allele frequency (MAF), and basic data management [11]. |

| GBLUP | Software / Model | Available in many mixed-model software packages. Used for genomic prediction assuming an infinitesimal model and for constructing genomic relationship matrices [6] [7]. |

| BGLR R Package | Software | A comprehensive R package for implementing a wide range of Bayesian regression models, including the entire "Bayesian Alphabet" (BayesA, B, C, LASSO, etc.) [8]. |

| SKM R Library | Software | A user-friendly R library for implementing seven common statistical machine learning methods (e.g., Random Forest, SVM, GBM) for genomic prediction, with built-in tools for cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning [14]. |

| Sparse Kernel Methods | Method | A class of kernel methods (e.g., Gaussian, Arc-cosine) that can capture complex, non-linear patterns and epistatic interactions more efficiently than deep learning for some datasets [12]. |

| Locally-Connected Layer (LCL) | Method | A deep learning layer used in networks like deepGBLUP. Unlike convolutional layers, it uses unshared weights, allowing it to assign marker effects based on their distinct genomic loci, which is more biologically appropriate for SNP data [11]. |

| N6-(2-Phenylethyl)adenosine | N6-(2-Phenylethyl)adenosine, MF:C18H21N5O4, MW:371.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 10-Formyl-7,8-dihydrofolic acid | 10-Formyl-7,8-dihydrofolic acid, CAS:25377-55-3, MF:C20H21N7O7, MW:471.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does trait heritability influence the required size of my reference population? Trait heritability ((h^2)) is a primary factor determining the achievable accuracy of Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs). For traits with low heritability, a larger reference population is required to achieve a given level of prediction accuracy. Simulation studies in Japanese Black cattle showed that for a trait with a heritability of 0.1, a reference population of over 5,000 animals was needed to achieve a high accuracy. In contrast, for a trait with a heritability of 0.5, a similar accuracy could be reached with a smaller population [15].

2. Is there a point of diminishing returns for marker density in genomic selection? Yes, genomic prediction accuracy typically improves as marker density increases but eventually reaches a plateau. Beyond this point, adding more markers does not meaningfully improve accuracy, allowing for cost-effective genotyping strategies.

- In mud crab, accuracy plateaued after using approximately 10,000 SNPs [16].

- In Pacific white shrimp, the accuracy saw diminishing returns after about 3,200 SNPs [17].

- In meat rabbits, a density of 50K SNPs was established as a suitable baseline [18].

- In olive flounder, using 3,000–5,000 randomly selected SNPs resulted in predictive ability similar to using 50,000 SNPs [19].

3. What is the minimum recommended size for a reference population? The minimum size is context-dependent, varying with the species' genetic diversity and the trait's heritability. However, some studies provide concrete guidelines:

- Mud crab: A reference population of at least 150 individuals was identified as a minimum standard for growth-related traits [16].

- Japanese Black cattle: For carcass traits (with (h^2) ~0.29-0.41), a reference population of 7,000–11,000 animals was sufficient to achieve accuracies (0.73–0.79) comparable to those from progeny testing [15].

- General finding: The accuracy of Genomic Selection (GS) consistently improves as the reference population size expands, as demonstrated in mud crabs where increasing the size from 30 to 400 individuals led to significant accuracy gains [16].

4. Do different genomic prediction models perform differently? The choice of model can be important, but studies across various species often find that the differences in prediction accuracy between common models (e.g., GBLUP, BayesA, BayesB, BayesC, rrBLUP) are often quite small [16] [17]. GBLUP is frequently noted for its computational efficiency and unbiased predictions when the reference population is sufficiently large [16]. Furthermore, multi-trait models can significantly improve accuracy for genetically correlated traits compared to single-trait models [18].

Table 1: The Interplay of Heritability, Reference Population Size, and Genomic Prediction Accuracy (Based on Simulation in Japanese Black Cattle)

| Trait Heritability ((h^2)) | Reference Population Size | Expected Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 5,000 | ~0.50 |

| 0.25 | 5,000 | ~0.65 |

| 0.50 | 5,000 | ~0.78 |

| 0.10 | 10,000 | ~0.58 |

| 0.25 | 10,000 | ~0.73 |

| 0.50 | 10,000 | ~0.84 |

Source: Adapted from [15]

Table 2: Observed Plateaus for Marker Density and Reference Population Size in Various Species

| Species | Trait Category | Marker Density Plateau | Minimum/Maximizing Reference Population Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mud Crab | Growth-related | ~10,000 SNPs [16] | Minimum: 150 [16] |

| Pacific White Shrimp | Growth | ~3,200 SNPs [17] | Not Specified |

| Japanese Black Cattle | Carcass | Not a primary focus | 7,000-11,000 for high accuracy [15] |

| Meat Rabbit | Growth and Slaughter | ~50,000 SNPs [18] | Not Specified |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Marker Density and Reference Population Size

This protocol outlines a general experimental workflow to determine the optimal marker density and reference population size for a genomic selection program, as implemented in studies on species like mud crab and shrimp [16] [17].

1. Population, Phenotyping, and Genotyping:

- Population: Establish a population of individuals with recorded pedigrees, ensuring a wide genetic diversity representative of the breeding population.

- Phenotyping: Accurately measure the target trait(s) of interest (e.g., body weight, carapace length) on all individuals.

- Genotyping: Genotype the entire population using a high-density SNP array or sequencing (e.g., low-coverage whole-genome sequencing) to obtain a comprehensive set of genome-wide markers [16] [18].

2. Data Quality Control (QC) and Imputation:

- Perform stringent QC on the genotypic data using software like PLINK. Common filters include removing markers with a low minor allele frequency (e.g., MAF < 0.05), high missing genotype rates (e.g., >10%), and significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [16] [15].

- Remove individuals with high missing genotype rates (e.g., call rate < 90%) [16].

- Impute any remaining missing genotypes using software such as Beagle [16] [15].

3. Genetic Parameter Estimation:

- Estimate the genomic heritability ((h^2)) of the trait using a genomic relationship matrix (GRM) and the GREML method implemented in software like GCTA [16].

- Estimate variance components to understand the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to genetics.

4. Testing Marker Density:

- Create random subsets of SNPs from the full, high-quality dataset at various densities (e.g., 0.5K, 1K, 5K, 10K, 20K, up to the full set) [16] [17].

- For each density subset, perform genomic prediction using a chosen model (e.g., GBLUP) and a cross-validation scheme.

- Calculate the prediction accuracy (e.g., correlation between GEBV and observed phenotype in the validation population) for each density.

- Identify the density where accuracy plateaus, indicating the cost-effective optimum.

5. Testing Reference Population Size:

- Randomly sample subsets of individuals from the full dataset at various sizes (e.g., 50, 100, 200, 400) to act as reference populations [16].

- Use the remaining individuals as the validation population.

- For each reference population size, perform genomic prediction and calculate the prediction accuracy.

- Plot accuracy against reference population size to visualize the relationship and identify points of diminishing returns.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Multi-Trait Genomic Selection Model

This protocol describes the steps to implement a multi-trait GBLUP model, which can improve prediction accuracy for genetically correlated traits [18].

1. Data Preparation:

- Collect phenotypic records for multiple traits and genotypic data for all individuals in the reference population.

- Perform the same QC and imputation steps as in Protocol 1.

2. Variance-Covariance Estimation:

- Estimate the genetic variance for each trait and the genetic covariance between each pair of traits. This creates the genetic variance-covariance matrix (M). This can be done using REML methods.

3. Model Fitting:

- Fit a multi-trait linear mixed model. The model for two traits can be specified as:

[

\begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{y1} \ \mathbf{y2} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{X1} & \mathbf{0} \ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{X2} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{b1} \ \mathbf{b2} \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{Z1} & \mathbf{0} \ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{Z2} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{a1} \ \mathbf{a2} \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{e1} \ \mathbf{e2} \end{bmatrix}

]

where:

- (\mathbf{y}) is the vector of phenotypic values for the two traits.

- (\mathbf{X}) and (\mathbf{Z}) are design matrices for fixed and random effects, respectively.

- (\mathbf{b}) is the vector of fixed effects (e.g., sex, batch).

- (\mathbf{a}) is the vector of additive genetic effects, assumed to follow (N(0, \mathbf{M} \otimes \mathbf{G})), where (\mathbf{G}) is the genomic relationship matrix.

- (\mathbf{e}) is the vector of random residuals [18].

4. Prediction and Validation:

- Use the fitted model to predict GEBVs for all traits in the validation population.

- Validate the model using cross-validation and compare its accuracy to single-trait models.

Workflow and Logical Relationships

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Genomic Prediction Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SNP Array | High-throughput genotyping platform for scoring thousands to hundreds of thousands of SNPs across the genome. | "Xiexin No. 1" 40K SNP array for mud crabs [16]; GGP BovineLD v4.0 for cattle [15]. |

| Low-Coverage Whole-Genome Sequencing (lcWGS) | A cost-effective method for genotyping by sequencing the entire genome at low depth, followed by imputation to a high-density variant set. | Genotyping in meat rabbits [18]. |

| PLINK | Software tool for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis; used for rigorous quality control of SNP data. | Filtering SNPs based on MAF, missingness, and HWE in cattle and shrimp studies [16] [17]. |

| Beagle | Software for phasing genotypes and imputing ungenotyped markers, crucial for handling missing data. | Imputing missing genotypes in mud crab and cattle studies [16] [15]. |

| GCTA | Software tool for Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis; used for estimating genomic heritability and genetic correlations. | Estimating variance components and heritability using the GREML method [16]. |

| rrBLUP / BGLR R Packages | R packages providing functions for genomic prediction, including RR-BLUP and various Bayesian models. | Fitting GBLUP and Bayesian models in various species [19] [17]. |

| Genomic Relationship Matrix (GRM) | A matrix quantifying the genetic similarity between individuals based on marker data; foundational for many prediction models. | Constructed from all SNPs to estimate additive genetic variance in mixed models [16] [15]. |

Understanding the Impact of Genetic Architecture on Parameter Selection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does genetic architecture influence the choice of a genomic prediction model? The genetic architecture of a trait—meaning the number of causal variants and the distribution of their effect sizes—is a primary factor in selecting an appropriate model.

- For highly polygenic architectures (many small-effect variants), models like gBLUP (Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction) or rrBLUP (ridge regression BLUP) are recommended. These models assume all markers have a small, normally distributed effect, which is a robust and computationally efficient approximation for many complex traits [1] [20].

- For traits influenced by a few moderate- to large-effect variants alongside many small effects, variable selection models like BayesB, BayesC, or LASSO are often more accurate. These methods allow some marker effects to be shrunk to zero, better capturing a "sparse" genetic architecture [1] [20].

- A simple initial GWAS Manhattan plot can guide model selection. Traits showing a few "spiked" signals may benefit from variable selection models, while those with a diffuse, polygenic background are well-suited to gBLUP [20].

FAQ 2: Why does my genomic prediction model show low accuracy even when heritability is high? Low prediction accuracy can stem from a mismatch between your model's assumptions and the true genetic architecture, or from population structure [21].

- Architecture-Model Mismatch: Applying an additive, infinitesimal model (like G-BLUP) to a trait governed largely by epistatic (non-additive) interactions can result in poor accuracy. In such cases, models that explicitly account for interactions can improve performance [21].

- Population Structure: High prediction accuracy in breeding populations is often driven by high relatedness and linkage disequilibrium (LD) between individuals. In populations of unrelated individuals (e.g., human cohorts or diverse plant lines) with low LD, accuracy will naturally be lower unless the genetic architecture is explicitly accounted for in the model [21] [22].

- Training Population Composition: The relatedness between the calibration (training) and validation sets significantly impacts accuracy. Including progenitors in the training set can dramatically improve the accuracy of predicting progeny performance [22].

FAQ 3: What is the practical difference between GBLUP and Bayesian models like BayesB? The core difference lies in their prior assumptions about how marker effects are distributed.

- GBLUP/rrBLUP assumes a single, normal distribution for all marker effects. This is the infinitesimal model, where every marker contributes a small effect, and no markers are excluded [1].

- BayesB assumes a mixture distribution. A proportion of markers are assumed to have zero effect, while the rest have effects drawn from a normal or t-distribution. This makes it a variable selection model, which is more flexible for traits with large-effect loci [1].

Table 1: Key Factors Affecting Genomic Prediction Accuracy

| Factor | Impact on Prediction Accuracy | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Trait Heritability | Positive correlation | Higher heritability generally enables higher prediction accuracy [22]. |

| Training Population Size | Positive correlation | Larger reference populations yield more accurate predictions [22]. |

| Relatedness & LD | Positive correlation | High relatedness and LD between training and target populations boost accuracy [21] [22]. |

| Genetic Architecture | Determines optimal model | Matching the model to the architecture (e.g., polygenic vs. sparse) is critical for maximizing accuracy [20] [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Genomic Prediction Accuracy

Observation: The correlation between predicted and observed values in the validation set is low.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Options to Resolve |

|---|---|---|

| Low prediction accuracy in unrelated individuals | Mismatch between genetic architecture and model assumption; Low LD | 1. Perform a GWAS to visualize genetic architecture (e.g., Manhattan plot) [20]. 2. Switch from GBLUP to a variable selection model (e.g., Bayesian LASSO) if large-effect loci are detected [1] [21]. 3. Incorporate significant variants from GWAS into a customized relationship matrix for prediction [21]. |

| Accuracy drops when predicting progeny performance | Recombination breaks down marker-QTL phases; Selection changes allele frequencies | 1. Include the parents of the target progeny population in the training set [22]. 2. Re-train models each generation using the most recent data to maintain accuracy [22]. |

| Low accuracy for a trait with known high heritability | Model is unable to capture non-additive genetic effects | 1. Use models that explicitly account for epistatic interactions [21]. 2. Ensure the training population is sufficiently large and has power to detect the underlying architecture [21]. |

Problem 2: Selecting the Wrong Model for Your Trait's Genetic Architecture

Observation: Uncertainty about which genomic prediction model to apply for a novel trait.

Table 2: Genomic Prediction Model Selection Guide Based on Genetic Architecture

| Model Category | Example Models | Assumed Genetic Architecture | Best For Traits That Show... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitesimal / Polygenic | GBLUP, rrBLUP | Many thousands of loci, each with a very small effect [1] | A "diffuse" Manhattan plot with no prominent peaks (e.g., human height) [20]. |

| Variable Selection | BayesB, BayesC, LASSO | A mix of zero-effect markers and markers with small-to-large effects [1] | A "spiked" Manhattan plot with a few significant peaks (e.g., some autoimmune diseases) [20]. |

| Flexible / Mixture | BayesR, DPR (Dirichlet Process Regression) | A flexible distribution that can adapt to various architectures, from sparse to highly polygenic [20] | An unknown or complex architecture, or when you want to avoid strong prior assumptions [20]. |

Diagnostic Strategy Flow:

- Visualize: Conduct a GWAS and examine the Manhattan plot for the trait [20].

- Classify: Categorize the architecture as "diffuse" (use GBLUP) or "spiked" (use variable selection).

- Test: Use cross-validation to compare the accuracy of 2-3 recommended models from the table above.

- Validate: Always validate the final model's predictive performance on an independent, untested dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Genomic Prediction Studies

| Item | Function in Genomic Prediction |

|---|---|

| High-Density SNP Array / Whole-Genome Sequencing | Provides the genome-wide molecular marker data (genotypes) required to build the genomic relationship matrix (GRM) and estimate marker effects [1]. |

| Phenotyped Training Population | A set of individuals with accurately measured traits of interest. The size and genetic diversity of this population are critical for model accuracy [22]. |

| Genomic Relationship Matrix (GRM) | A matrix quantifying the genetic similarity between all pairs of individuals based on marker data. It is the foundational component of models like GBLUP [1]. |

| Linear Mixed Model (LMM) Software | Software packages (e.g., GCTA, BLR, BGLR) that implement various genomic prediction algorithms to estimate breeding values and partition genetic variance [1] [20]. |

| GLP-1 receptor agonist 11 | GLP-1 receptor agonist 11, CAS:2784590-83-4, MF:C31H31ClFN3O4, MW:564.0 g/mol |

| SPSB2-iNOS inhibitory cyclic peptide-1 | SPSB2-iNOS inhibitory cyclic peptide-1, MF:C35H56N12O14S2, MW:933.0 g/mol |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: Assessing Prediction Accuracy Across Generations

This protocol is based on a study in maritime pine [22] and is crucial for validating models in a breeding context.

1. Design the Reference Population:

- Select individuals covering multiple generations (e.g., G0 founders, G1 parents, G2 progeny).

- Use pedigree and phenotype information for pre-selection, aiming to control effective population size.

- Genotype all individuals using a high-density SNP array.

2. Define Calibration and Validation Sets:

- Within-Generation Validation: Split a single generation (e.g., G1) into training and testing sets to establish a baseline accuracy.

- Across-Generation (Progeny) Validation: Use earlier generations (G0 and G1) as the calibration set to predict the breeding values of the progeny generation (G2). This tests the model's practical utility.

3. Run Genomic Prediction Models:

- Apply multiple models (e.g., ABLUP-pedigree, GBLUP-markers, Bayesian LASSO) to the same calibration set.

- Use the models to generate Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs) for the validation set.

4. Calculate Prediction Accuracy:

- For the validation set, calculate the correlation between the predicted GEBVs and the observed phenotypes (or pedigree-based EBVs).

- Compare accuracies between different models and validation designs to determine the most robust strategy.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Genetic Architecture Decision Workflow

Diagram 2: Genomic Prediction Experimental Process

Advanced Methods and Practical Implementation Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When should I choose GBLUP over a Bayesian model like BayesC for my genomic prediction task?

Your choice should be guided by the underlying genetic architecture of your trait and your computational resources.

- Opt for GBLUP when you are working with polygenic traits influenced by many genes with small effects. GBLUP assumes all markers contribute equally to the genetic variance and is highly robust across various scenarios. It is also computationally efficient and less prone to convergence issues [23] [24].

- Choose BayesC when you have prior knowledge or suspicion that the trait is influenced by a fewer number of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) with larger effects. BayesC performs variable selection by assuming that only a fraction of markers have a non-zero effect, which can be advantageous for traits with low to moderate numbers of QTLs [23] [24].

The table below summarizes the key differences to guide your selection:

| Feature | GBLUP | BayesC |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Assumption | All markers have an effect, following an infinitesimal model [25]. | Only a fraction ((\pi)) of markers have a non-zero effect; performs variable selection [26]. |

| Best for Trait Architecture | Polygenic traits with many small-effect QTLs [24]. | Traits with a low to moderate number of QTLs or major genes [24]. |

| Computational Demand | Generally faster and less computationally intensive [27]. | More demanding, often requiring Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods [26]. |

| Impact of Heritability | Tends to perform more consistently across heritability levels; can be better for low-heritability traits [23]. | Prediction advantage can become more obvious as heritability increases [23]. |

2. How do factors like heritability and marker density affect prediction accuracy, and how can I optimize them?

Prediction accuracy is influenced by several factors, and understanding their interaction is key to optimizing your model.

- Heritability: Higher heritability generally leads to higher prediction accuracy for all models. GBLUP has been shown to be particularly robust for traits with low heritability, while Bayesian methods like BayesC may show a greater relative advantage as heritability increases [23].

- Marker Density: Increasing marker density typically improves accuracy by providing better genome coverage and capturing more causative variants [23]. However, the gain depends on the model and trait. For complex, polygenic traits, GBLUP with high-density markers is effective. When using sequence data with many non-causal variants, Bayesian variable selection models like BayesC can be more efficient at identifying the true signals [26].

The following workflow diagram outlines the decision process for configuring your model based on these factors:

3. My Bayesian model (e.g., BayesC) is running very slowly or failing to converge. What can I do?

Slow performance and convergence issues are common challenges with MCMC-based Bayesian models. Here are several troubleshooting steps:

- Verify Model Configuration: Ensure your prior distributions and the value of (\pi) (in BayesC) are appropriately set for your data. Misspecified priors can lead to poor mixing and slow convergence.

- Check Diagnostic Metrics: Use convergence diagnostics like (\hat{R}) (R-hat), which should be ≤ 1.01 for modern best practices, and examine trace plots to ensure chains are well-mixed and stationary [28].

- Consider Computational Shortcuts: For large datasets, especially those involving whole-genome sequence data, consider using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD). SVD can be applied to the genotype matrix to directly estimate marker effects for models like BayesC in a non-iterative, computationally efficient manner, achieving similar accuracies to traditional MCMC methods [26].

- Simplify the Model: If troubleshooting fails, a simpler model like GBLUP can be a robust alternative, especially for highly polygenic traits, and is much faster to compute [23] [25].

4. Are there alternatives to traditional regression models for genomic selection?

Yes, reformulating the problem can sometimes yield better results for specific breeding objectives.

- Binary Classification Approach: You can reformulate genomic selection as a binary classification problem. Instead of predicting a continuous breeding value, you classify individuals as "top" or "not top" performers based on a threshold (e.g., the 90th percentile or the performance of a check variety). Training a classification model this way can significantly increase sensitivity for selecting the best candidate lines [29].

- Machine Learning Models: Non-parametric methods like Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM are also used. Benchmarking studies have shown they can offer modest gains in accuracy and major computational advantages in fitting time compared to some Bayesian methods, though they require careful hyperparameter tuning [27].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Protocol for Implementing and Comparing GBLUP and BayesC

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for a standard genomic prediction analysis, allowing for a fair comparison between GBLUP and BayesC.

1. Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Genotypic Data: Start with your raw genotype matrix. Perform quality control (QC) by filtering out markers with a high missing rate (e.g., >10-20%) and a low minor allele frequency (e.g., MAF < 0.05) [25]. Impute remaining missing genotypes using software like Beagle [27].

- Phenotypic Data: Collect and pre-process phenotypic records. Correct for fixed effects (e.g., herd, year, sex) if necessary, often by using Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUEs) or de-regressed breeding values.

2. Model Training & Cross-Validation

- Population Splitting: Use a k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) scheme. Randomly divide the population into k subsets. Iteratively use k-1 folds as the training set to estimate model parameters and the remaining fold as the validation set to assess accuracy [23] [25].

- Model Implementation:

- GBLUP: Fit the model by solving its mixed model equations (MMEs). The genomic relationship matrix (G) is calculated from the scaled and centered genotype matrix Z as G = ZZ' / m, where m is the number of markers [25].

- BayesC: Fit the model using an MCMC algorithm (e.g., Gibbs sampling). Specify prior distributions for the marker effects and the parameter (\pi). Run a sufficient number of iterations, discarding the initial iterations as burn-in.

3. Evaluation and Accuracy Calculation

- The primary metric for evaluation is the prediction accuracy, calculated as the correlation between the genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) and the observed (or corrected) phenotypic values in the validation set [25] [24].

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key resources and datasets essential for benchmarking and implementing genomic prediction models.

| Resource / Solution | Function / Description | Relevance to Model Selection |

|---|---|---|

| EasyGeSe Database [27] | A curated collection of ready-to-use genomic and phenotypic datasets from multiple species (barley, maize, pig, rice, etc.). | Provides standardized data for fair benchmarking of new methods (e.g., GBLUP vs. BayesC) across diverse genetic architectures. |

| RR-BLUP / GBLUP R package [25] | An R package (e.g., rrBLUP) that provides efficient functions like mixed.solve() for implementing GBLUP and RR-BLUP models. |

Essential for the practical application of GBLUP, allowing estimation of breeding values and genomic heritability. |

| Stan or PyMC3 Software [28] | Advanced platforms that use Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) for efficient fitting of complex Bayesian models. | Useful for implementing custom Bayesian models like BayesC, though they require careful troubleshooting of MCMC diagnostics. |

| Beagle Imputation Software [27] | A software tool for phasing and imputing missing genotypes in genotype data. | A critical pre-processing step to ensure high-quality, complete genotype data for both GBLUP and Bayesian models. |

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) [26] | A matrix decomposition technique that can be applied to the genotype matrix. | A computational shortcut to enable fast, non-MCMC-based estimation for models like BayesC, especially with large WGS data. |

| PTP1B-IN-3 diammonium | PTP1B-IN-3 diammonium, MF:C12H13BrF2N3O3P, MW:396.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anti-inflammatory agent 31 | Anti-inflammatory agent 31, MF:C19H30O3, MW:306.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the field of genomic prediction, the accurate selection and tuning of machine learning models are paramount for translating vast genomic datasets into meaningful biological insights and predictive models. Among the plethora of available algorithms, Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) and Gradient Boosting, specifically through its advanced implementation XGBoost, have demonstrated exceptional performance in handling the complex, high-dimensional nature of genomic data. KRR combines the kernel trick, enabling the capture of nonlinear relationships, with ridge regression's regularization to prevent overfitting. In contrast, XGBoost employs an ensemble of decision trees, sequentially built to correct errors from previous trees, offering robust predictive power. However, the sophisticated process of hyperparameter tuning presents a significant barrier to their wider application in actual breeding and drug development programs. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and detailed methodologies to empower researchers in overcoming these challenges, thereby accelerating breeding progress and enhancing predictive accuracy in genomic selection [30].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My Kernel Ridge Regression model is severely overfitting the training data. What are the primary parameters to adjust?

A: Overfitting in KRR typically occurs when the model complexity is too high for the dataset. To address this, focus on the following parameters and strategies:

- Increase Regularization (

alpha): Thealphaparameter controls the strength of the L2 regularization. A larger value (e.g., 1.0, 10.0) penalizes large coefficients more heavily, reducing model complexity and variance. Start with a logarithmic search between (10^{-3}) and (10^{3}) [31] [32]. - Tune the Kernel Parameter (

gammafor RBF): If using the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, thegammaparameter defines the influence of a single training example. A low value implies a large similarity radius, resulting in smoother models. A very highgammacan lead to overfitting. Use techniques like Bayesian optimization to find an optimal value [33]. - Re-evaluate Your Kernel Choice: A polynomial kernel with a very high degree might be too complex. Consider switching to a linear kernel or an RBF kernel with careful tuning if nonlinearity is necessary [34].

- Use Automated Hyperparameter Tuning: Employ advanced optimization techniques like the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) to automatically find the best combination of

alphaandgamma. Studies have shown that KRR integrated with TPE (KRR-TPE) can achieve higher prediction accuracy compared to manual tuning or grid search, with an average improvement of 8.73% in prediction accuracy reported in some genomic studies [30].

Q2: The training time for my KRR model is prohibitively long on a large genomic dataset. Why is this, and what can I do?

A: The computational complexity of KRR is (O(n^3)), where (n) is the number of training instances, due to the inversion of a dense (n \times n) kernel matrix [34]. This becomes a major bottleneck with large-scale genomic data.

- Lack of Sparsity: Unlike Support Vector Machines, KRR does not produce a sparse solution. The model uses all training instances to make a prediction, which is computationally expensive at both training and prediction time [32] [34].

- Strategies for Mitigation:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply feature selection or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of features or instances before training.

- Approximation Methods: Use the Nyström method or random Fourier features to approximate the kernel matrix, which can significantly reduce computational costs.

- Subsampling: Train the model on a representative random subset of your data to establish a baseline before scaling up with more efficient algorithms.

Q3: How can I interpret which features are most important in my complex XGBoost model for genomic prediction?

A: While XGBoost models are complex, you can gain interpretability through feature importance scores. The plot_importance function provides different views of a feature's influence [35].

- Gain ('gain'): This is the average improvement in model performance (or loss reduction) when a feature is used for splitting. It is often the most reliable metric for understanding a feature's contribution to predictive accuracy [35].

- Weight ('weight'): This counts the number of times a feature is used in a split across all trees. A high count indicates frequent use but does not necessarily correlate with large performance gains [35].

- Cover ('cover'): This is the average number of samples affected by splits involving the feature. It can reveal if a feature is used in splits that impact many instances or only a few [35].

- Insight: By comparing these plots, you can understand different nuances. For example, a feature like median income might be top-ranked by gain and weight but lower by cover, suggesting it is used in many specific, high-impact splits that affect relatively few samples [35].

Q4: I am getting poor performance with XGBoost on a genomic dataset with a large number of markers. How can I improve it?

A: Poor performance can stem from various issues. Systematic hyperparameter tuning is crucial.

- Tune Key Parameters:

learning_rate: Step size shrinkage to prevent overfitting. A smaller value (e.g., 0.01-0.1) requires more trees (n_estimators) but often leads to better generalization.max_depth: The maximum depth of a tree. Controls model complexity; shallower trees are more robust to noise.subsample: The fraction of instances used for training each tree. Using less than 1.0 (e.g., 0.8) introduces randomness and helps prevent overfitting.colsample_bytree: The fraction of features used for each tree. Useful in high-dimensional settings, like genomics, to force the model to use different subsets of markers [35] [36].

- Use Bayesian Optimization: Instead of a computationally expensive grid search, use Bayesian optimization (e.g., with a Tree-structured Parzen Estimator) to efficiently navigate the hyperparameter space and find an optimal configuration, similar to the approach used for KRR [30] [37].

Table 1: Key Hyperparameters for KRR and XGBoost

| Model | Hyperparameter | Description | Common Values / Search Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Ridge Regression | alpha |

Regularization strength; improves conditioning and reduces overfitting. | (10^{-3} ) to (10^{3}) (log scale) [31] [32] |

kernel |

Kernel function for non-linear mapping. | 'linear', 'rbf', 'poly' [32] | |

gamma (RBF) |

Inverse influence radius of a single training example. | (10^{-3} ) to (10^{3}) (log scale) [31] | |

| XGBoost | learning_rate |

Shrinks feature weights to make boosting more robust. | 0.01 - 0.3 [35] [36] |

max_depth |

Maximum depth of a tree; controls model complexity. | 3 - 10 [35] | |

n_estimators |

Number of boosting trees or rounds. | 100 - 1000 [35] | |

subsample |

Fraction of samples used for training each tree. | 0.5 - 1.0 [35] | |

colsample_bytree |

Fraction of features used for training each tree. | 0.5 - 1.0 [35] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Hyperparameter Tuning with Bayesian Optimization for Genomic Prediction

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for tuning KRR and XGBoost models using Bayesian optimization, a strategy proven to achieve superior prediction accuracy in genomic datasets [30].

1. Problem Formulation and Objective Definition:

- Objective: Maximize the prediction accuracy (e.g., Pearson correlation coefficient, ( R^2 )) between the Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs) and observed phenotypes in a validation set via k-fold cross-validation.

- Search Space: Define the bounds for each hyperparameter on a log scale where appropriate.

- For KRR:

alpha((10^{-4}, 10^{2})),gamma((10^{-4}, 10^{2})). - For XGBoost:

learning_rate(0.01, 0.3),max_depth(3, 10),subsample(0.6, 1.0).

- For KRR:

2. Optimization Setup with Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE):

- Surrogate Model: Use TPE, which models (P(x|y)) and (P(y)), to construct a probabilistic model of the objective function.

- Acquisition Function: Use the Expected Improvement (EI) criterion to decide the next hyperparameter set to evaluate. EI balances exploration (trying uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining known good regions) [30] [33].

3. Iterative Optimization Loop:

- Initialization: Start with a small number (e.g., 5-10) of randomly selected hyperparameter configurations.

- For i = 1 to N_evaluations:

- Fit Surrogate: Update the TPE surrogate model with all observed

(hyperparameters, score)pairs. - Propose Next Point: Find the hyperparameter set (x^*) that maximizes the acquisition function.

- Evaluate Objective: Run a 5-fold cross-validation with the proposed hyperparameters (x^) on the training data to get the objective score (y^).

- Update Data: Append the new observation ((x^, y^)) to the history.

- Fit Surrogate: Update the TPE surrogate model with all observed

- Output: The hyperparameter set that achieved the highest objective score during the optimization loop.

4. Final Model Training and Validation:

- Train the final KRR or XGBoost model on the entire training set using the optimized hyperparameters.

- Assess the final model's performance on a held-out test set that was not used during the tuning process.

Table 2: Comparison of Hyperparameter Tuning Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Pros | Cons | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search | Exhaustive search over a predefined set of values. | Simple, parallelizable, thorough. | Computationally intractable for high dimensions or fine grids. | Small, low-dimensional parameter spaces. |

| Random Search | Randomly samples parameters from distributions. | More efficient than grid search; better for high dimensions. | May miss important regions; not intelligent. | A good baseline for moderate-dimensional spaces. |

| Bayesian Optimization (e.g., TPE) | Builds a probabilistic model to guide the search. | Highly sample-efficient; finds good parameters quickly. | More complex to set up; overhead of modeling. | Expensive objective functions (e.g., genomic KRR/XGBoost) [30]. |

Workflow Diagram: KRR with Bayesian Optimization for Genomic Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow for tuning a KRR model using Bayesian optimization within a genomic prediction context.

KRR Bayesian Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Genomic Prediction with KRR and XGBoost

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Array | Provides raw genomic marker data (SNPs). | Illumina BovineHD BeadChip (cattle), Illumina PorcineSNP60 (pigs) [30]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Tools | Filters noisy or unreliable genetic markers. | PLINK: Used for QC to remove SNPs based on missingness, Minor Allele Frequency (MAF), and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [30]. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Library | Automates the search for optimal model parameters. | Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE): Integrated with KRR to achieve state-of-the-art prediction accuracy in genomic studies [30]. |

| Machine Learning Framework | Provides implementations of KRR and XGBoost. | scikit-learn: Contains the KernelRidge class for KRR modeling [31] [32]. XGBoost: Dedicated library for the XGBoost algorithm with a scikit-learn-like API [35] [38]. |

| Feature Importance Interpreter | Helps interpret complex models by quantifying feature contributions. | XGBoost's plot_importance: Visualizes feature importance by 'gain', 'weight', or 'cover' to identify key genomic regions [35]. |

| Sp-8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMPS | Sp-8-pCPT-2'-O-Me-cAMPS, MF:C17H17ClN5O5PS2, MW:501.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Phytic acid hexasodium | Phytic acid hexasodium, MF:C6H12Na6O24P6, MW:791.93 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Concepts and Integration Strategies

Integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics data is essential for obtaining a comprehensive view of biological systems, as it connects upstream genetic activity with downstream functional phenotypes. Several computational strategies have been developed to effectively combine these data types, each with distinct advantages and applications.

Table 1: Categories of Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

| Integration Category | Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | Applies statistical correlations between omics datasets and represents relationships via networks [39]. | Identifies co-expression/co-regulation patterns; Uses Pearson correlation; Constructs gene-metabolite networks [39]. |

| Machine Learning | Utilizes one or more omics data types with algorithms for classification, regression, and pattern recognition [39]. | Can capture non-linear relationships; Suitable for prediction tasks; Includes neural networks, deep learning [40] [39]. |

| Multi-Staged | Assumes unidirectional flow of biological information (e.g., from genome to metabolome) [41]. | Models cascading biological processes; Hypothesis-driven; Often used in metabolic pathway analysis [41]. |

| Meta-Dimensional | Assumes multi-directional or simultaneous variation across omics layers [41]. | Data-driven; Can reveal novel interactions; Often uses concatenation or model fusion [41] [40]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the most effective method for predicting the spatial distribution of transcripts or metabolites? For tasks involving spatial distribution prediction, methods like Tangram, gimVI, and SpaGE have demonstrated top performance in benchmark studies [42]. The choice depends on your specific data characteristics, such as resolution and technology platform (e.g., 10X Visium, MERFISH, or seqFISH). These integration methods effectively combine spatial transcriptomics data with single-cell RNA-seq data to predict the distribution of undetected transcripts [42].

FAQ 2: Which integration approaches consistently improve predictive accuracy in genomic selection models? Our evaluation of 24 integration strategies reveals that model-based fusion techniques consistently enhance predictive accuracy over genomic-only models, especially for complex traits. In contrast, simpler concatenation approaches often underperform. When integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics, methods that capture non-additive, nonlinear, and hierarchical interactions across omics layers yield the most significant improvements [40].

FAQ 3: How can I identify key regulatory nodes and pathways connecting gene expression with metabolic changes? Gene-metabolite network analysis is particularly effective for this purpose. This approach involves collecting gene expression and metabolite abundance data from the same biological samples, then integrating them using correlation analysis (e.g., Pearson correlation coefficient) to identify co-regulated genes and metabolites. The resulting network, visualized with tools like Cytoscape, helps pinpoint key regulatory nodes and pathways involved in metabolic processes [39].

FAQ 4: What are the common pitfalls in sample preparation for transcriptomics-metabolomics integration studies? Inconsistent sample handling is a major source of error. For metabolomics, it is crucial to completely block all enzymes and biochemical reactions by quenching metabolic pathways and metabolite isolation immediately upon collection. This creates a stable extract where metabolite ratios and concentrations reflect the endogenous state. Careful sample collection and metabolite extraction are essential to maintain analyte concentrations, increase instrument productivity, and reduce analytical matrix effects [43].

FAQ 5: My multi-omics data have different dimensionalities and measurement scales. What integration strategy handles this best? Intermediate integration strategies are specifically designed to address this challenge. These methods involve a data transformation step performed prior to modeling, which helps normalize the inherent differences in data dimensionality, measurement scales, and noise levels across various omics platforms. Techniques such as neural encoder-decoder networks can transform disparate omics data into a shared latent space, making the datasets comparable and integrable [41].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Gene-Metabolite Network Construction

Objective: To construct and analyze a gene-metabolite interaction network from paired transcriptomics and metabolomics data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological samples (tissue, plasma, urine, etc.)

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy)

- Metabolite extraction solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile)

- LC-MS or GC-MS system for metabolomics

- RNA-seq platform for transcriptomics

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect and split biological samples for parallel transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis under identical conditions [39].

- Data Generation:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize gene expression data (e.g., TPM or FPKM for RNA-seq).

- Normalize metabolomics data (e.g., pareto scaling for MS data).

- Correlation Analysis:

- Calculate Pearson correlation coefficients (PCC) between all gene-metabolite pairs [39].

- Apply statistical thresholds (e.g., p-value < 0.05, |PCC| > 0.8) to identify significant associations.

- Network Construction:

- Import significant gene-metabolite pairs into network visualization software (e.g., Cytoscape) [39].

- Nodes represent genes and metabolites; edges represent significant correlations.

- Network Analysis:

- Identify highly connected nodes (hubs) using topology measures (degree, betweenness centrality).

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on gene clusters within the network.

- Validation:

- Validate key findings using orthogonal methods (e.g., qPCR for genes, targeted MS for metabolites).

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Ensure biological replicates (n ≥ 5) to achieve sufficient statistical power for correlation analysis.

- Address batch effects through randomized sample processing and ComBat normalization if needed.

- For heterogeneous tissues, consider single-cell or spatial transcriptomics to resolve cell-type-specific connections.

Workflow Visualization: Multi-Omics Integration for Genomic Prediction

Multi-Omics Integration Workflow for Genomic Prediction

Method Selection and Benchmarking

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method Category | Top-Performing Methods | Primary Use Case | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Tangram, gimVI, SpaGE [42] | Spatial distribution prediction of RNA transcripts | Outperform other methods for predicting spatial distribution of undetected transcripts [42]. |

| Cell Type Deconvolution | Cell2location, SpatialDWLS, RCTD [42] | Cell type deconvolution of spots in histological sections | Top-performing for identifying cell types within spatial transcriptomics spots [42]. |

| Multi-Omics Prediction | Model-based fusion techniques [40] | Genomic prediction of complex traits | Consistently improve predictive accuracy over genomic-only models, especially for complex traits [40]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics-Metabolomics Integration

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Separation and quantification of complex molecules in metabolomics [43]. | Ideal for non-volatile or thermally labile compounds; can be enhanced with UPLC/UHPLC [43]. |

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Analysis of small molecular substances (< 650 Daltons) in metabolomics [43]. | Best for volatile compounds; requires chemical derivatization for some metabolites [43]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Detection and structural characterization of metabolites without extensive sample preparation [43]. | Measures chemical shifts of atomic nuclei (e.g., 1H, 31P, 13C); excellent for quantification [43]. |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA for transcriptomics studies. | Critical for obtaining reliable gene expression data; choice depends on sample type (tissue, cells, etc.). |

| Cytoscape | Network visualization and analysis for gene-metabolite interactions [39]. | Enables construction and interpretation of correlation networks from integrated data [39]. |

| (Z)-Ganoderenic acid K | (Z)-Ganoderenic acid K, MF:C32H44O9, MW:572.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Sedoheptulose 7-phosphate | D-Sedoheptulose 7-phosphate, MF:C7H13O10P-2, MW:288.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization: Correlation-Based Integration

Correlation-Based Integration Workflow

In genomic prediction, a fundamental tension exists between statistical accuracy and computational practicality. As breeding programs increasingly rely on genomic selection (GS) to accelerate genetic gain, researchers are faced with complex decisions regarding model selection, parameter tuning, and resource allocation. The primary goal is to develop workflows that are not only biologically insightful and statistically powerful but also efficient and scalable for real-world application. This technical support guide addresses common pitfalls and questions encountered when balancing these competing demands, with a specific focus on parameter tuning for genomic prediction models. The following sections provide targeted troubleshooting advice, data-driven recommendations, and practical protocols to optimize your computational workflows.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Managing Computational Cost and Model Complexity

Problem Statement: A research team finds that their deep learning model for genomic prediction requires excessive computational time and resources, making it infeasible for routine use in their breeding program.

Diagnosis: This is a common issue when complex, non-linear models are applied without considering the trade-offs between marginal gains in accuracy and substantial increases in computational cost.

Solution Steps:

- Benchmark Against simpler Models: Before deploying a complex model, always establish a baseline performance using a simpler, more efficient model like GBLUP. The GBLUP model is known for its reliability, scalability, and ease of interpretation [44].

- Evaluate the Accuracy-Complexity Trade-off: Determine if the deep model's potential accuracy improvement is justified. Studies show that while Deep Learning (DL) can outperform GBLUP, especially for capturing non-linear genetic patterns, it does not do so consistently across all traits and scenarios. Its success is highly dependent on careful parameter optimization [44].

- Optimize Hyperparameters Systematically: For DL models, invest time in a systematic hyperparameter tuning process. This includes adjusting the number of hidden layers, units per layer, and learning rate to maximize predictive accuracy without overfitting [44].

- Consider Two-Stage Models: For large-scale breeding programs, implement fully-efficient two-stage models. These models first calculate adjusted genotypic means and then predict Genomic Breeding Values (GEBVs). They can handle spatial variation and complex experimental designs (like augmented designs) much more efficiently than single-stage models, often with comparable or better accuracy [45].

Guide 2: Selecting an Optimal SNP Panel Density

Problem Statement: A research group wants to implement genomic selection for a new aquaculture species but needs to minimize genotyping costs. They are unsure how many SNPs are necessary for accurate predictions.

Diagnosis: The prediction accuracy of GS typically improves with higher marker density but eventually plateaus. Using more markers than necessary incurs superfluous cost without meaningful benefit.

Solution Steps:

- Conduct a SNP Density Analysis: Use your own data or a representative subset to evaluate how prediction accuracy changes as you sequentially increase the number of SNPs used in the model.

- Identify the Plateau Point: The goal is to find the density where accuracy gains diminish. For example, a study on growth traits in mud crab found that prediction accuracy improved as SNP density increased from 0.5K to 33K, but began to plateau after approximately 10K SNPs [46].

- Select the Cost-Effective Panel: Choose a SNP panel that is at or just above the identified plateau point. For the mud crab, a panel of 10K SNPs was determined to be a cost-effective minimum standard for growth-related traits [46].

- Validate with Different Models: Ensure this finding holds across multiple statistical models (e.g., GBLUP, BayesB) used in your pipeline.

Guide 3: Determining an Adequate Reference Population Size

Problem Statement: A plant breeder has a limited budget for phenotyping and genotyping and needs to know the minimum number of individuals required to start a functional genomic selection program.

Diagnosis: The size of the reference population is a critical factor influencing prediction accuracy. An undersized population leads to unreliable models, while an oversized one wastes resources.

Solution Steps:

- Perform a Reference Size Simulation: Analyze how the prediction accuracy and unbiasedness of your models change as you vary the size of the training population.

- Establish a Minimum Viable Size: Research suggests a population size threshold for reliable predictions. In mud crabs, a reference population of at least 150 samples was necessary to achieve stable and unbiased predictions for growth-related traits [46].

- Prioritize Continuous Expansion: Understand that accuracy generally improves with a larger reference population. The same study showed that expanding the population from 30 to 400 individuals increased prediction accuracy by ~4-9% across different traits [46]. Therefore, plan for gradual expansion of your training set over time.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary purpose of troubleshooting and optimizing a bioinformatics pipeline? The primary purpose is to identify and resolve errors or inefficiencies in computational workflows. This ensures the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of your data analysis while managing computational costs and time. Efficient pipelines are crucial for transforming raw data into meaningful biological insights, especially when scaling to large datasets [47].

Q2: When should I start optimizing my bioinformatics workflows? Optimization should be considered when your data processing demands scale and justify the cost. It is an ongoing process, but key triggers include:

- Scaling Needs: When semi-manual workflows become unstable or too slow for your data volume.

- Cost Escalation: When computational costs for processing millions of data points become significant.

- Project Planning: Ideally, invest in scalable infrastructure early to allow workflows to expand alongside your research needs [48].

Q3: How can I improve the biological relevance of my genomic prediction model? Incorporate prior biological knowledge to guide feature selection. For instance, the binGO-GS framework uses Gene Ontology (GO) annotations as a biological prior to select SNP markers that are functionally related. This approach stratifies SNPs based on GWAS p-values and uses a bin-based combinatorial optimization to select an optimal marker subset, which has been shown to improve prediction accuracy over using the full marker set [49].

Q4: What are the common challenges in bioinformatics pipeline troubleshooting? You will likely encounter several common challenges:

- Data Quality Issues: Low-quality reads or contaminated datasets.

- Tool Compatibility: Conflicts between software versions or dependencies.

- Computational Bottlenecks: Insufficient resources or inefficient algorithms slowing down processing.

- Error Propagation: Mistakes in early stages (e.g., alignment) affecting downstream results.