Optimizing Mutation Rates in Genetic Algorithms: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to mutation rate optimization in genetic algorithms (GAs), tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science.

Optimizing Mutation Rates in Genetic Algorithms: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to mutation rate optimization in genetic algorithms (GAs), tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science. It explores the foundational principles of mutation, examines cutting-edge methodological approaches including adaptive and fuzzy logic systems, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies to avoid premature convergence and stagnation. By presenting validation frameworks and comparative analyses from recent studies in quantum computing and genomics, this resource equips scientists with the knowledge to enhance GA performance for complex biological optimization problems, from protein design to therapeutic discovery.

Understanding Mutation Rates: The Core Engine of Genetic Algorithm Evolution

Defining Mutation Rate and Its Role in Population Diversity

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What exactly does "mutation rate" refer to in a genetic algorithm? The term "mutation rate" can have different interpretations in practice, and there is no single universally agreed-upon definition [1]. Most commonly, in the context of a binary-encoded genetic algorithm, it refers to β, the probability that a single bit (or allele) in a genetic sequence will be flipped [1] [2]. However, it is also sometimes defined as the probability that a given gene is modified, or even the probability that an entire chromosome is selected for mutation [1]. The implementation depends on the specific problem and representation.

Q2: What is the primary role of mutation in genetic algorithms? Mutation serves two critical purposes:

- To introduce and maintain genetic diversity within the population, preventing premature convergence to local optima by allowing the algorithm to explore new regions of the search space [3] [2].

- To act as a local search operator, fine-tuning existing solutions. Small, random changes can lead to incremental improvements, especially in the later stages of the algorithm [2].

Q3: How do I choose an appropriate mutation rate? Selecting a mutation rate is a balance between exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining good solutions). The table below summarizes common values and heuristics [2]:

| Rate Type / Heuristic | Typical Value or Formula | Impact and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Rate | 1/L (L = chromosome length) | A common default that balances exploration and exploitation [2]. |

| Fixed Rate | 0.01 (1%) | A low rate that favors exploitation; suitable for smooth fitness landscapes [2]. |

| Fixed Rate | 0.05 (5%) | A moderate rate for a general balance [2]. |

| Fixed Rate | 0.1 (10%) | A high rate that emphasizes exploration; useful for rugged landscapes or low diversity [2]. |

| Adaptive Rate | Decreases over time | Encourages exploration early and exploitation later [2]. |

| Heuristic | Inversely proportional to population size | Smaller populations need higher rates to maintain diversity [2]. |

Q4: What are the common signs of an incorrect mutation rate and how can I fix them?

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Premature Convergence (Population becomes homogeneous, progress stalls) [4] | Mutation rate too low; insufficient diversity. | Increase the mutation rate. Use adaptive mutation. Increase population size. Employ niching techniques (e.g., fitness sharing) [4]. |

| Erratic Performance (Good solutions are frequently disrupted, the algorithm fails to refine answers) [2] | Mutation rate too high; excessive randomness. | Decrease the mutation rate. Implement elitism to preserve the best solutions [4]. |

Q5: What are some common mutation operators for different genome types? The choice of mutation operator is heavily dependent on how your solution is encoded [3] [5].

| Genome Encoding | Mutation Operator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Binary String | Bit Flip [3] [2] | Each bit has a independent probability of being flipped (0→1, 1→0). |

| Real-Valued / Continuous | Gaussian (Normal) Distribution [3] | A small random value drawn from a normal distribution is added to each gene. |

| Permutations | Swap Mutation [5] | Two genes are randomly selected and their positions are swapped. |

| Permutations | Inversion Mutation [3] [5] | A random substring is selected and the order of its genes is reversed. |

| Permutations | Insertion Mutation [5] | A single gene is selected and inserted at a different random position. |

| Real-Valued | Creep Mutation [5] | A small random vector is added to the chromosome, or a single element is perturbed. |

Experimental Protocols for Mutation Rate Optimization

This section provides a methodology for conducting experiments to optimize the mutation rate for a specific problem, as would be performed in a research context.

Protocol 1: Establishing a Baseline with Fixed Mutation Rates

Objective: To determine the impact of a range of fixed mutation rates on algorithm performance and solution quality.

Materials and Reagents (The Researcher's Toolkit):

- Computational Environment: A computer with sufficient processing power and memory to run multiple iterations of the genetic algorithm. AWS services like Amazon SageMaker Processing can be used for parallel, large-scale experiments [6].

- Programming Language: Python (recommended for extensive library support) or another suitable language.

- Data Structure: A defined genome representation (e.g., bitstring, list of real numbers, permutation) for the problem [6].

- Fitness Function: A well-defined function that can evaluate the quality of any given genome [6].

Methodology:

- Problem Definition: Select a well-defined benchmark problem (e.g., the "OneMax" problem for bitstrings or the "Travelling Salesman Problem" for permutations) [2] [6].

- Parameter Setup: Define all other genetic algorithm parameters and keep them constant throughout the experiment:

- Population Size: 100

- Crossover Rate: 0.8

- Selection Method: Tournament Selection

- Number of Generations: 500

- Elitism: Preserve top 1-5 individuals [4]

- Experimental Groups: Run the genetic algorithm multiple times (e.g., 30 runs for statistical significance) for each of the fixed mutation rates listed in the table in Q3.

- Data Collection: For each run, record:

- The best fitness found.

- The generation at which the best fitness was found.

- The average population fitness over generations.

- A population diversity metric (e.g., average Hamming distance) at regular intervals [4].

- Analysis: Use statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA) to compare the performance (best fitness, convergence speed) across the different mutation rate groups. The optimal rate is the one that consistently yields the best fitness without causing excessive instability.

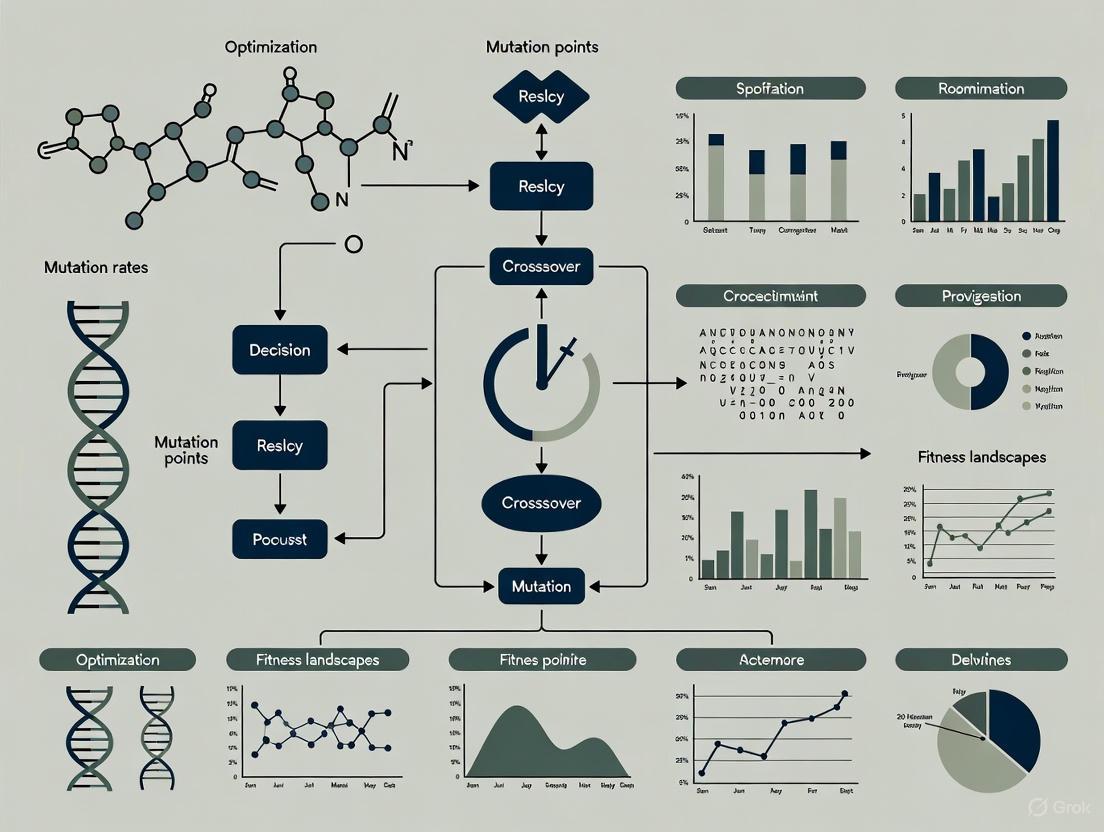

The following workflow graph illustrates the experimental process:

Protocol 2: Implementing and Testing an Adaptive Mutation Rate

Objective: To design and evaluate an adaptive mutation strategy that dynamically adjusts the rate based on population diversity.

Methodology:

- Baseline: Use the optimal fixed mutation rate found in Protocol 1 as a control.

- Diversity Metric: Implement a function to calculate population diversity. For bitstrings, this is often the average Hamming distance between all individuals in the population [4]. For real-valued genes, Euclidean distance can be used [4].

- Adaptive Rule: Define a rule for adjusting the mutation rate. For example:

if (population_diversity < threshold) then mutation_rate = min(max_rate, mutation_rate * 1.1)- This increases the mutation rate when diversity becomes too low.

- Experimental Run: Conduct multiple runs of the genetic algorithm using the adaptive strategy, collecting the same data as in Protocol 1.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the performance (final best fitness, convergence speed, and maintained diversity) of the adaptive strategy against the best fixed rate.

The logic of the adaptive mutation mechanism is shown below:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What do "exploration" and "exploitation" mean in the context of Genetic Algorithms (GAs)?

In GAs, exploration refers to the process of searching new and unknown regions of the solution space to discover potentially better solutions. It is associated with the algorithm's global search ability and is primarily driven by operators like mutation. Conversely, exploitation refers to the process of intensifying the search around previously discovered good solutions to refine them. It is associated with local search and is heavily influenced by selection and crossover operators. The core challenge in optimizing a GA is to find a effective balance between these two competing forces [7] [8].

2. How does the mutation rate specifically affect this balance?

The mutation rate is a critical parameter controlling this balance. A low mutation rate (e.g., 0.001 to 0.01) favors exploitation by making small, incremental changes, helping to fine-tune existing solutions. However, it can lead to premature convergence if the population loses diversity too quickly. A high mutation rate (e.g., 0.05 to 0.1) favors exploration by introducing more randomness, helping the algorithm escape local optima. But if set too high, it can disrupt good solutions and turn the search into a random walk, hindering convergence [9]. A common guideline is to set the initial mutation rate inversely proportional to the chromosome length [9].

3. What are the common signs that my GA is poorly balanced?

You can identify balance issues by monitoring the algorithm's performance over generations:

- Signs of Too Much Exploitation (Premature Convergence): The population's fitness improves very quickly but then stalls at a suboptimal level. Genetic diversity within the population drops rapidly and remains low [9].

- Signs of Too Much Exploration (Slow or No Convergence): The population's fitness improves very slowly or not at all across generations. The algorithm fails to refine promising areas of the search space, and high genetic diversity persists without a corresponding improvement in solution quality [9].

4. Beyond mutation rate, what other parameters can I adjust to improve balance?

Several other parameters and strategies significantly impact the exploration-exploitation dynamic:

- Population Size: Larger populations (e.g., 100 to 1000 for complex problems) naturally maintain more diversity, aiding exploration [9].

- Crossover Rate: A moderate to high rate (0.6 to 0.9) is typical for exploiting good genetic material from parents [9].

- Selection Pressure: Methods like tournament selection allow you to control how strongly the algorithm biases selection towards the fittest individuals. Higher pressure favors exploitation [7].

- Elitism: Preserving the best individual(s) from one generation to the next ensures exploitation of the best-known solution but can be combined with exploratory operators for balance [9].

5. Are there advanced strategies to dynamically manage this balance?

Yes, advanced methods involve adaptive parameter control. Instead of keeping rates fixed, the algorithm adjusts them based on runtime performance. For example, if the fitness has not improved for a predefined number of generations (e.g., 50), the mutation rate can be temporarily increased to boost exploration and help the algorithm escape the local optimum [9]. Other research explores attention mechanisms to assign weights to different decision variables, balancing the search at a more granular level [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios and Solutions

| Scenario | Symptoms | Probable Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Premature Convergence | Fitness stalls early; low population diversity; suboptimal solution. | Over-exploitation; mutation rate too low; high selection pressure [9]. | 1. Increase mutation rate (e.g., to 0.1).2. Increase population size.3. Reduce tournament size or use a less aggressive selection method.4. Introduce/increase elitism cautiously. |

| Slow or No Convergence | Fitness improves very slowly; high diversity persists; no solution refinement. | Over-exploration; mutation rate too high; low selection pressure [9]. | 1. Decrease mutation rate (e.g., to 0.01).2. Decrease population size.3. Increase selection pressure (e.g., larger tournament size).4. Implement a stronger elitism strategy. |

| Performance Instability | Wide variation in best fitness across runs; unpredictable results. | Over-reliance on randomness; poorly tuned parameters. | 1. Use a fixed random seed for debugging.2. Implement adaptive parameter control [9].3. Use fitness scaling (e.g., rank-based) to normalize selection pressures [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimizing Mutation Rates

Protocol 1: Establishing a Baseline

This protocol is designed to find a starting point for mutation rate tuning using a systematic approach.

1. Objective: Determine a effective static mutation rate for a specific problem domain and representation. 2. Materials/Reagents:

- A standardized benchmark problem relevant to your domain (e.g., Travelling Salesman Problem for combinatorial optimization) [7] [11].

- Your GA framework with configurable parameters. 3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Set all other GA parameters to a conservative default (e.g., Population Size=100, Crossover Rate=0.8, Generations=500).

- Step 2: Select a range of mutation rates to test (e.g., 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1).

- Step 3: For each mutation rate, execute a minimum of 30 independent GA runs to account for stochasticity.

- Step 4: For each run, log key metrics including final best fitness, generation of convergence, and population diversity over time. 4. Data Analysis: Compare the average and standard deviation of the final best fitness across the different mutation rates. The rate that yields the best consistent results provides a baseline for further refinement.

Protocol 2: Implementing Adaptive Mutation

This protocol outlines a method for creating a self-adjusting mutation rate to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation.

1. Objective: Implement and validate an adaptive mutation strategy that responds to search stagnation. 2. Materials/Reagents: The same as in Protocol 1. 3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Start with the baseline mutation rate determined in Protocol 1.

- Step 2: Define a stagnation threshold (e.g., no improvement in best fitness for 50 generations).

- Step 3: Implement a rule to increase the mutation rate by a factor (e.g., 1.5) whenever the stagnation threshold is crossed [9].

- Step 4: Optionally, implement a rule to gradually reset or decrease the mutation rate after an improvement is found.

- Step 5: Execute multiple runs and compare performance against the best static baseline from Protocol 1. 4. Data Analysis: Use non-parametric statistical tests (like the Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to determine if the adaptive method provides a statistically significant improvement in final solution quality compared to the static baseline [7].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for implementing an adaptive mutation rate strategy within a genetic algorithm.

Adaptive Mutation Rate Control Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions for experiments focused on balancing exploration and exploitation in Genetic Algorithms.

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Problems (e.g., TSP, Symbolic Regression) | Standardized test functions and real-world problems used to evaluate and compare the performance of different GA parameter sets and strategies [7] [11]. |

| Diversity Metrics | Quantitative measures (e.g., genotype or phenotype diversity) used to monitor the population's exploration state and diagnose premature convergence [7]. |

| Fixed Random Seeds | A software technique to ensure that GA runs with different parameters are initialized with the same pseudo-random number sequence, making performance comparisons fair and deterministic during debugging [9]. |

| Statistical Comparison Tools | Non-parametric statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and critical difference diagrams used to rigorously validate the performance difference between algorithmic variants [7]. |

| Fitness Landscape Analysis | Methods to characterize the topology of the optimization problem (smooth, rugged, multi-modal) which informs the choice of a suitable balance between exploration and exploitation [8]. |

Standard Mutation Rate Ranges and Initial Parameter Selection

This guide provides foundational knowledge and practical methodologies for researchers initiating experiments with Genetic Algorithms in scientific domains such as drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a typical starting point for the mutation rate? A common and widely cited starting point is a mutation rate of 1/L, where L is the length of the chromosome [12]. For general problems, values between 0.001 (0.1%) and 0.1 (10%) are typical [9] [13]. For binary chromosomes, a bit flip mutation rate of 1/L is often effective.

My algorithm converges too quickly to a suboptimal solution. How can I adjust the mutation? This is a classic sign of premature convergence. To encourage more exploration of the search space, you can gradually increase the mutation rate within the suggested range. Alternatively, implement an adaptive mutation rate that increases when the population diversity drops or when no fitness improvement is observed over a number of generations [9].

The algorithm is not converging and seems to be searching randomly. What should I check? This behavior often indicates that the mutation rate is too high, causing excessive disruption to good solutions. Try progressively lowering the mutation rate. Also, verify that your selection pressure is sufficiently high to favor fitter individuals and that your crossover rate is adequately promoting the mixing of good genetic material [9] [13].

How do I choose a mutation operator? The choice depends heavily on how your solution is encoded (e.g., binary string, permutation, real numbers). The table below summarizes common operators and their applications.

Mutation Operator Selection Guide

| Mutation Operator | Description | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|

| Bit Flip [14] | Flips the value of a single bit/gene (0 to 1 or 1 to 0). | Binary-encoded problems (e.g., feature selection). |

| Swap [14] | Randomly selects and swaps two elements within a chromosome. | Order-based problems like scheduling or routing (TSP). |

| Inversion [14] | Reverses the order of a contiguous segment of genes. | Problems where gene sequence and linkage are critical. |

| Scramble [14] | Randomly shuffles the order of genes within a selected segment. | Problems with complex gene interactions to disrupt blocks. |

| Random Resetting [14] | Resets a gene to a new random value from the allowable set. | Non-binary encodings, including integer and real values. |

Establishing Your Initial Parameters

There is no single parameter set that works best for all problems [12]. The following table provides recommended starting ranges based on established practices and literature. These should be used as a baseline for your initial experiments.

| Parameter | Recommended Starting Range | Notes and Common Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | 0.001 - 0.1 (0.1% - 10%) [9] [13] | Start with 1 / (Chromosome Length) [12]. Higher rates favor exploration. |

| Population Size | 50 - 1000 [9] | Use 20-100 for small problems; 100-1000 for complex ones [9]. A size of 100-200 is common for a "standard" GA [12]. |

| Crossover Rate | 0.6 - 0.9 (60% - 90%) [9] [13] | Higher rates are typical as crossover is the primary operator for exploitation. |

| Number of Generations | Variable | Run until convergence or a fitness plateau is reached. Track the number of fitness evaluations (Population Size × Generations) for a fair comparison [12]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Parameter Optimization

For robust research, especially within a thesis, moving beyond static parameters is advisable. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach for tuning mutation rates, incorporating dynamic strategies.

Dynamic Parameter Control: Instead of fixed rates, let parameters change linearly over generations. Research has shown this can be highly effective [13].

- Strategy: DHM/ILC: Start with a high mutation rate (e.g., 100%) and a low crossover rate (0%). Decrease mutation and increase crossover over time. This is effective for small population sizes, encouraging broad exploration early and refinement later [13].

- Strategy: ILM/DHC: Start with a low mutation rate and a high crossover rate, then invert them. This can be more effective for larger population sizes [13].

Experimental Tuning Protocol:

- Start with Defaults: Use the baseline values from the table above [9].

- Change One Parameter at a Time: To isolate effects, vary only the mutation rate while keeping population size and crossover rate constant.

- Use a Fixed Seed: Initialize your random number generator with a fixed seed for different runs to ensure results are comparable.

- Track Progress: Log the best and average fitness per generation. Calculate diversity metrics (e.g., average Hamming distance) to understand population dynamics [9] [12].

- Implement Early Stopping: Terminate the run if fitness does not improve over a predefined number of generations (e.g., 50-100) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

When designing and reporting your GA experiments, the following components are crucial for reproducibility and success.

| Item / Concept | Function in the GA Experiment |

|---|---|

| Chromosome Encoding | The representation of a candidate solution (e.g., Binary, Permutation, Value) [13]. The choice dictates suitable mutation operators. |

| Fitness Function | The objective function that evaluates the quality of a solution, guiding the search [15]. |

| Selection Operator | The mechanism (e.g., Tournament, Roulette Wheel) for choosing parents based on fitness, controlling selection pressure [13]. |

| Crossover Operator | The operator that combines genetic material from two parents to create offspring, key for exploitation [16]. |

| Mutation Operator | The operator that introduces random changes, maintaining population diversity and enabling exploration [14]. |

| Benchmarking Suite | A set of standard problems (e.g., TSPLIB for TSP) used to validate and compare algorithm performance [13]. |

| Evaluation Metric | A measure like "number of fitness function evaluations" to fairly compare algorithms against computational budget [12]. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My genetic algorithm is converging prematurely. How can insights from genomic studies help? Biological systems avoid uniformity through context-dependent mutation rates. Research shows mutation rates vary by over twenty-fold across the genome, with repetitive regions being particularly mutation-prone [17]. Implement a non-uniform mutation strategy that identifies and targets "hotspot" areas of your solution space, similar to how tandem repeats in DNA have higher mutation rates [18].

Q2: How do I determine the optimal baseline mutation rate for my problem? Studies across organisms reveal that mutation rates are shaped by a trade-off between exploring new solutions and maintaining existing function [19] [20]. Start with a low rate (e.g., analogous to the human SNM rate of ~10⁻⁸ per site [21]) and increase only if population diversity drops. E. coli experiments show populations with initially high mutation rates often evolve to reduce them, suggesting overly high rates can be detrimental long-term [20].

Q3: Should mutation rates be static or dynamic during a run? Biological evidence strongly supports dynamic control. Mutation rates in Escherichia coli can change rapidly (within 59 generations) in response to environmental and population-genetic challenges [20]. Implement adaptive mutation rates that respond to population diversity metrics or generation count, decreasing as your algorithm converges to refine solutions.

Q4: How do I handle different types of mutations in my algorithm? Genomic studies categorize and quantify diverse mutation types [22]. The table below summarizes mutation rates observed in mammalian studies. Consider implementing a similar spectrum in your GA, with higher rates for certain operations (e.g., "indels") that mimic biological mechanisms like microsatellite expansion/contraction.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Loss of Critical Genetic Material

- Biological Insight: Genomic studies show not all regions mutate equally; some are protected [17] [18].

- Solution: Implement "essential gene" protection in your GA. Identify core building blocks of good solutions and apply a lower mutation rate to these segments.

Problem: Algorithm Fails to Find High-Fitness Regions

- Biological Insight: Under stress, some bacteria increase mutation rates to enhance adaptation [20].

- Solution: Introduce a stress response mechanism. Temporarily increase the mutation rate or introduce stronger mutations when fitness plateaus for a set number of generations.

Problem: Excessive Disruption of Good Solutions

- Biological Insight: DNA repair mechanisms constantly correct errors, keeping most mutations in check [19].

- Solution: Add a "repair" operator to your GA that fixes newly generated solutions violating core constraints, acting as a local search around new mutants.

Quantitative Data from Biological Studies

| Mutation Class | Rate Per Transmission | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) | 74.5 | Strong paternal bias (75-81%) |

| Non-Tandem Repeat Indels | 7.4 | Small insertions/deletions |

| Tandem Repeat Mutations | 65.3 | Most mutable class measured |

| Centromeric Mutations | 4.4 | Previously difficult to study |

| Y Chromosome Mutations | 12.4 | In male transmissions only |

| Total DNMs | 98-206 | Depends on genomic context |

| Mutation Type | Average per Haploid Genome per Generation | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Nucleotide Mutations (SNMs) | ~20 | 44% |

| Small Indels (<50 bp) | ~24 | 54% |

| Large Structural Mutations (SMs) | ~1 | 2% |

| Total | ~45 | 100% |

| Transfer Scheme & Background | SNM Rate Change | SIM Rate Change | Key Environmental Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| L10 (WT) | 121.4x increase | 77.3x increase | Intermediate resource replenishment (10 days) |

| L10 (MMR-) | 4.4x increase | Not Significant | Intermediate resource replenishment (10 days) |

| S1 (WT) | 1.5x increase | 3.1x increase | Severe bottleneck (1/10⁷ dilution) |

| S1 (MMR-) | 41.6% decrease | 48.2% decrease | Severe bottleneck (1/10⁷ dilution) |

Experimental Protocols for Mutation Rate Analysis

Purpose: To measure spontaneous mutation rates without the confounding effects of natural selection.

Methodology:

- Isolate Clones: Begin with a set of initially isogenic lines or populations.

- Minimize Selection: Subject populations to repeated severe bottlenecks (e.g., transferring only a single individual) to minimize the efficiency of natural selection, allowing even deleterious mutations to accumulate.

- Accumulate Mutations: Maintain lines for a known number of generations.

- Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS): Sequence the genomes of the end-point clones and the ancestral progenitor.

- Variant Calling: Identify fixed mutations by comparing the final genomes to the ancestor.

Key Considerations:

- The number of lines and generations determines the resolution and power of the experiment.

- Fitness measurements of the accumulated lines can provide estimates of the deleterious mutation rate.

Purpose: To directly observe the transmission and de novo origin of mutations in a controlled lineage.

Methodology:

- Select Pedigree: Choose a large, multigenerational family (e.g., three- or four-generation).

- Multiple Technologies: Sequence multiple members using complementary technologies (e.g., PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore, Illumina) to achieve high accuracy and assembly continuity.

- Phased Assembly: Generate complete, phased diploid genome assemblies for each individual.

- Variant Phasing and Transmission: Track the inheritance of every genomic segment and its associated variants across generations.

- Identify De Novo Mutations (DNMs): Identify mutations present in a child but absent in both parents.

Key Considerations:

- Allows distinction between germline and postzygotic mosaic mutations.

- Provides a "truth set" for validating mutation calls and understanding regional variation in mutation rates.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Multigenerational Mutation Study Workflow

Diagram 2: Biological Principles for GA Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Genomic Mutation Rate Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Generates highly accurate long reads for resolving complex genomic regions and detecting structural variants. | Phasing haplotypes and calling mutations in repetitive regions within a pedigree [18]. |

| Oxford Nanopore (UL-ONT) | Produces ultra-long reads for spanning large repeats and achieving near-telomere-to-telomere (T2T) assemblies. | Assembling centromeres and other gap regions in reference genomes [18]. |

| Strand-Seq | A single-cell sequencing method that templates DNA strands, ideal for detecting structural variants and phasing. | Identifying large inversions and validating assembly accuracy [18]. |

| Mutation Accumulation (MA) Lines | Biological repositories where mutations are allowed to accumulate with minimal selection for direct rate measurement. | Estimating baseline mutation rates and spectra in model organisms like C. elegans and E. coli [19] [20]. |

| T2T-CHM13 Reference Genome | A complete, gapless human genome reference that enables mapping and analysis of previously inaccessible regions. | Providing an unbiased framework for variant discovery across the entire genome, including centromeres [18]. |

Advanced Methods for Dynamic Mutation Rate Control in Practice

Core Concepts: Static and Dynamic Mutation Rates

FAQ: What is the fundamental difference between static and dynamic mutation rates?

A static mutation rate is a fixed probability applied to each gene throughout the entire run of the Genetic Algorithm (GA). It is typically set to a low value, often in the range of 0.5% to 2% for character-based chromosomes, or around 1% (1/𝑙) for binary representations, where 𝑙 is the chromosome length [23] [24]. In contrast, a dynamic mutation rate is not fixed; it changes during the evolutionary process. These changes can be predetermined (e.g., decreasing linearly over generations) or adaptive, responding to the population's state, such as increasing when diversity drops [13].

FAQ: Why is mutation so critical in Genetic Algorithms?

Mutation is an essential genetic operator because crossover alone cannot generate new genetic material; it can only recombine what already exists in the population [23]. Mutation introduces fresh genetic variations, which helps to:

- Prevent Premature Convergence: It stops the GA from getting stuck in local optima early in the search [23].

- Maintain Population Diversity: It introduces new alleles, preventing all chromosomes from becoming too similar [23].

- Enable Exploration: It allows the algorithm to discover parts of the search space that are not reachable through crossover alone [23] [24].

However, it is crucial to strike a balance. A mutation rate that is too high can cause the GA to degenerate into a random search, while one that is too low may lead to stagnation [23].

Quantitative Comparison and Guidelines

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of static and dynamic mutation rate strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Static and Dynamic Mutation Rate Strategies

| Feature | Static Mutation Rate | Dynamic Mutation Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A fixed, constant probability applied to all genes in every generation. | A probability that changes based on a schedule or in response to the population's state. |

| Typical Range | 0.5% - 2% for character sequences; ~1/𝑙 for binary strings [23] [24]. | Varies widely, e.g., from 100% to 0%, or adapts to fitness/diversity metrics [13]. |

| Implementation | Simple to implement and requires no monitoring of the algorithm's progress. | More complex; requires a predefined schedule or a mechanism to calculate diversity/fitness. |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity and computational efficiency. | Enhanced ability to balance exploration (early) and exploitation (late) in the search. |

| Key Disadvantage | May require extensive prior experimentation to tune and cannot adapt to changing search needs. | Increased complexity and potential computational overhead from monitoring population state. |

| Best Suited For | Well-understood problems or as an initial baseline for experimentation. | Complex problems where the search landscape is unknown or likely to require shifting strategies. |

Experimental Protocols and Evidence

Detailed Methodology: Comparing Mutation Strategies on TSP

A key study compared dynamic and static mutation approaches on Traveling Salesman Problems (TSP) [13]. The protocol was as follows:

- Problem Encoding: Permutation encoding was used, where each chromosome represents a sequence of cities [13].

- Dynamic Strategies: Two novel dynamic approaches were tested:

- DHM/ILC (Dynamic Decreasing High Mutation / Dynamic Increasing Low Crossover): Started with a 100% mutation rate and 0% crossover rate. These ratios linearly changed over generations until they reached 0% for mutation and 100% for crossover by the end of the run [13].

- ILM/DHC (Dynamic Increasing Low Mutation / Dynamic Decreasing High Crossover): Operated inversely, starting with 0% mutation and 100% crossover, and linearly shifting to 100% mutation and 0% crossover [13].

- Static Comparisons: The dynamic methods were compared against two static parameter settings:

- A fifty-fifty (50%/50%) ratio for crossover and mutation.

- A common static ratio of a high crossover rate (0.9) and a low mutation rate (0.03) [13].

- Key Finding: The experimental results demonstrated that both proposed dynamic methods outperformed the predefined static methods in most test cases. Specifically, DHM/ILC was particularly effective with small population sizes, while ILM/DHC was more effective with large population sizes [13].

Detailed Methodology: Mutation in Quantum Circuit Synthesis

Recent research in 2025 has investigated mutation strategies for optimizing quantum circuits [25]. The experimental workflow is depicted below.

Diagram 1: GA Workflow for Quantum Circuit Optimization

- Candidate Representation: A quantum circuit is represented as a one-dimensional list of quantum operations (gates) and the qubits they target [25].

- Fitness Function: The fitness of a circuit candidate is derived from its quantum state fidelity (how close it is to the target state), circuit depth, and the number of costly T operations [25].

- Mutation Strategies: Several mutation techniques were tested on circuits with 4-6 qubits, including:

- Change: Altering a single gate to another.

- Delete: Removing a gate from the circuit.

- Add: Inserting a new gate.

- Swap: Exchanging the positions of two gates [25].

- Key Finding: The study found that a combination of delete and swap mutation strategies outperformed other approaches. It also highlighted the importance of hyperparameter tuning, such as adjusting mutation rates after each repetition for optimal performance [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GA Experiments

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Encoding Scheme | The method for representing a solution as a chromosome (e.g., Binary, Permutation, Value, Tree encoding). The choice dictates the problem's search space [13] [26]. |

| Fitness Function | The objective function that evaluates a chromosome's quality. It directly guides the evolutionary search toward the problem's goal [13] [25]. |

| Selection Operator | The mechanism for choosing parents for reproduction (e.g., Tournament Selection, Roulette Wheel). It applies selective pressure based on fitness [13] [26]. |

| Crossover Operator | The primary operator for recombining genetic material from two parents to produce offspring. It is typically applied with a high probability (e.g., 0.9) [13]. |

| Population Diversity Metric | A measure (e.g., genotypic diversity, fitness variance) used to monitor the population's state. It is crucial for triggering adaptive changes in dynamic mutation rates [23]. |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

FAQ: My GA is converging to a suboptimal solution too quickly. What can I do?

This is a classic sign of premature convergence, often linked to a loss of diversity.

- Solution 1: If you are using a static mutation rate, try a slight increase within the recommended range (e.g., from 1% to 1.5%-2%) to reintroduce variation [23].

- Solution 2: Implement a dynamic mutation strategy. Consider a method that increases the mutation rate when a drop in population diversity is detected. Alternatively, test a schedule that starts with a higher mutation rate to encourage exploration and gradually decreases it to refine solutions [13].

- Solution 3: Ensure your crossover rate is not too low, as crossover is the primary driver for exploiting good building blocks. A common effective static ratio is a high crossover rate (e.g., 0.9) paired with a low mutation rate (e.g., 0.03) [13].

FAQ: My GA is behaving erratically and not converging. How can I stabilize it?

This indicates excessive randomness, likely from over-mutation.

- Solution 1: Reduce your mutation rate. For static rates, ensure you are using a low probability (e.g., 0.5%-1% for character sequences). The

1/𝑙heuristic, where 𝑙 is the chromosome length, is a good starting point for binary encodings [23] [24]. - Solution 2: Combine mutation with crossover effectively. Mutation should be applied as a fine-tuning step after crossover, not as the main search driver. A standard practice is:

child = parent1.Crossover(parent2); child.Mutate(0.01);[23]. - Solution 3: For dynamic strategies, review the logic that increases the mutation rate. It might be triggering too aggressively. The probabilities of beneficial mutation naturally decrease as the population gets closer to an optimum, so the optimal mutation radius should also decrease over time [24].

FAQ: How do I choose between a static or dynamic approach for a new problem?

- Start with a Static Baseline: Begin your experimentation with the well-established static parameters: a high crossover rate (e.g., 0.9) and a low mutation rate (e.g., 0.01-0.03). This provides a performance benchmark [13] [23].

- Consider Problem Characteristics: If your problem has a very large and complex search space where exploration is critical, or if you notice your static GA consistently stagnates, a dynamic approach is a strong candidate to try next [13].

- Consider Computational Overhead: If your fitness function is extremely expensive to evaluate, the simplicity of a static rate might be preferable. If evaluation is cheap, you can afford the extra computation for adaptive mechanisms [13].

The decision between static and dynamic mutation rates is not about finding a universally superior option, but about matching the strategy to your specific problem and research goals. Static rates offer simplicity and reliability for well-understood problems, while dynamic rates provide a powerful, adaptive tool for navigating complex and uncharted search landscapes. The empirical evidence from domains as diverse as the TSP and quantum circuit synthesis strongly indicates that adopting a dynamic mindset can lead to significant performance improvements.

Implementing Adaptive Mutation Based on Fitness Stagnation

What is Adaptive Mutation?

Adaptive mutation is an advanced technique in genetic algorithms (GAs) where the mutation rate is dynamically adjusted during the optimization process instead of remaining a fixed, user-defined parameter. This dynamic adjustment is typically driven by feedback from the algorithm's own progress, such as a lack of improvement in fitness over successive generations, a phenomenon known as fitness stagnation [9] [27].

The core premise is to create a self-tuning algorithm that automatically balances exploration (searching new areas of the solution space) and exploitation (refining known good solutions). When the population diversity is low and fitness stagnates, the mutation rate increases to promote exploration. Conversely, when the population is making steady progress, the mutation rate decreases to allow finer exploitation of promising regions [2] [13].

Theoretical Basis: Why Use Fitness Stagnation?

Fitness stagnation serves as a key indicator that a genetic algorithm may be trapped in a local optimum or is experiencing a loss of diversity. Research has shown a non-linear relationship between mutation rate and the speed of adaptation; while higher mutation rates can accelerate adaptation, excessively high rates can be detrimental by disrupting good solutions [28].

Implementing an adaptive strategy based on fitness stagnation directly addresses this by:

- Preventing Premature Convergence: It helps the population escape local optima by introducing more variation when needed [29] [30].

- Maintaining Genetic Diversity: It counteracts the natural tendency of selection operators to reduce population diversity over time [2].

- Automating Parameter Tuning: It reduces the need for researchers to find a single, optimal static mutation rate, which is often problem-dependent and difficult to determine a priori [31] [13].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Basic Stagnation Detection and Response

This protocol outlines a fundamental approach to implementing adaptive mutation, suitable for integration into most standard GA frameworks [9].

Workflow Overview The following diagram illustrates the core logic of this adaptive mutation process, which is integrated into the main generational loop of a standard genetic algorithm.

Detailed Methodology

- Initialization:

- Set the initial mutation rate (

p_m). A common starting point is 0.05 (5%) or a value based on chromosome length, such as1 / LwhereLis the length of the bitstring [9] [2]. - Define the stagnation threshold (

N): This is the number of consecutive generations without improvement in the best fitness that will trigger an adaptive response. A typical starting value is 50 generations [9]. - Initialize a counter (

stagnation_counter) to zero.

- Set the initial mutation rate (

Generational Loop:

- Run a standard GA cycle: selection, crossover, mutation (using the current

p_m), and fitness evaluation. - After each generation, compare the best fitness value to the best fitness value from the previous generation.

- If the fitness improves: Reset

stagnation_counterto 0. Optionally, decrease the mutation rate slightly (e.g.,p_m = p_m / 1.5) to promote exploitation [9]. - If the fitness does not improve: Increment

stagnation_counterby 1. - If

stagnation_counter >= N: The population is deemed stagnant. Trigger the adaptive response:- Increase the mutation rate. A common method is to multiply it by a factor, for example:

p_m = p_m * 1.5[9]. - Reset

stagnation_counterto 0 after adjustment.

- Increase the mutation rate. A common method is to multiply it by a factor, for example:

- Run a standard GA cycle: selection, crossover, mutation (using the current

Bounds Checking: It is good practice to define a minimum and maximum allowable value for

p_m(e.g., between 0.001 and 0.5) to prevent it from becoming ineffective or overly disruptive.

Protocol 2: A Dynamic, Linearly Scaled Approach

This protocol, inspired by formal research, uses a deterministic method to change mutation and crossover rates linearly over the course of a run [13]. It frames adaptation not as a reactive event, but as a continuous process.

Methodology Two primary strategies have been proposed:

DHM/ILC (Decreasing High Mutation / Increasing Low Crossover):

- Start: Mutation Rate = 100%, Crossover Rate = 0%.

- Each Generation: Linearly decrease the mutation rate and increase the crossover rate.

- End: Mutation Rate = 0%, Crossover Rate = 100%.

- This strategy is particularly effective with small population sizes [13].

ILM/DHC (Increasing Low Mutation / Decreasing High Crossover):

- Start: Mutation Rate = 0%, Crossover Rate = 100%.

- Each Generation: Linearly increase the mutation rate and decrease the crossover rate.

- End: Mutation Rate = 100%, Crossover Rate = 0%.

- This strategy is more effective with large population sizes [13].

Implementation Steps:

- Set the total number of generations (

G). - For DHM/ILC, calculate the mutation rate (

p_m) for generationgas:p_m(g) = 1.0 - (g / G). - Similarly, calculate the crossover rate (

p_c) as:p_c(g) = g / G. - Use these dynamically calculated rates in the respective genetic operators for that generation.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My algorithm is now much slower after implementing adaptive mutation. Why? A: This is likely due to the increased computational cost from higher mutation rates. More mutations lead to more new genetic material that must be evaluated each generation. Ensure your fitness function is optimized. Also, consider implementing a more efficient stagnation detection check, such as checking for improvement only every 5-10 generations instead of every single one.

Q2: The mutation rate keeps increasing until it's too high, and the population becomes random. How can I prevent this? A: Your adaptive strategy lacks bounds. Always define a sensible maximum mutation rate (e.g., 0.3 or 30%) to prevent the algorithm from devolving into a random search. Furthermore, consider adding a "reset" condition that returns the mutation rate to its baseline after a severe stagnation period has passed [9] [2].

Q3: What is a good initial value for the stagnation threshold (N)?

A: There is no universal value, as it depends on problem complexity. A rule of thumb is to set N to 5-10% of your total expected generation count. Start with N=50 for a run of 1000 generations and adjust based on observation. If the algorithm triggers too often, increase N; if it gets stuck for long periods, decrease N [9].

Q4: Can I use adaptive mutation for real-valued (non-binary) gene representations? A: Absolutely. The core principle remains the same. You would adjust the parameters controlling your real-valued mutation operator, such as the step size (σ) in Gaussian mutation. For example, you could increase σ when stagnation is detected to take larger steps in the search space [32].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Symptom | Likely Cause | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Premature Convergence | Best fitness plateaus at a suboptimal value very early in the run. | Stagnation threshold (N) is too high; mutation rate is too low to escape local optimum. |

Decrease N to trigger a response sooner. Increase the multiplier used to boost the mutation rate [29]. |

| Erratic Performance | Wide variation in results between runs with the same seed; no consistent improvement. | Mutation rate is being increased too aggressively or is already too high. | Reduce the multiplier for increasing mutation rate (e.g., use 1.2 instead of 1.5). Implement a lower maximum bound for the mutation rate [28] [13]. |

| Failure to Converge | The best fitness fluctuates wildly and never stabilizes, even near the end of a run. | The algorithm is stuck in a perpetual "exploration" mode and cannot exploit good solutions. | Implement a mechanism to gradually reduce the baseline mutation rate over time, or use the ILM/DHC strategy which starts with low mutation [13]. |

| No Adaptive Response | The algorithm behaves identically to the non-adaptive version. | Logic error in stagnation detection or parameter update. | Add debug print statements to log the value of the stagnation counter and the mutation rate each generation to verify the adaptive logic is triggering correctly. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers aiming to implement and validate adaptive mutation strategies, the following "reagents" — in this context, software tools and performance metrics — are essential.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Problem Suite | To provide a standardized testbed for comparing the performance of different adaptive strategies. | Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) [13], Knapsack Problem [30], or real-valued optimization benchmarks (e.g., Sphere, Rastrigin functions). |

| Fitness Diversity Metric | To quantitatively measure the genetic diversity within the population, offering an alternative or supplement to stagnation detection. | Hamming Distance (for binary strings): Average pairwise distance between individuals. Niche Count: Number of unique fitness values or genotypes in the population [30]. |

| Parameter Tuning Configurator | To automate the process of finding good initial parameters for the GA and the adaptive strategy itself. | Software tools like irace or SMAC can systematically explore parameter spaces (e.g., initial p_m, stagnation threshold N, increase multiplier) to find robust configurations [31]. |

| Graphing & Visualization Library | To create diagnostic plots that illustrate the interplay between mutation rate, fitness, and diversity over generations. | Python libraries like Matplotlib or Seaborn. Essential for visualizing the adaptive process and diagnosing issues [9]. |

| Statistical Testing Framework | To rigorously determine if the performance improvement of an adaptive method is statistically significant over a static baseline. | Using Wilcoxon signed-rank test or Mann-Whitney U test to compare the final best fitnesses from multiple independent runs of adaptive vs. non-adaptive GAs [13]. |

Advanced Strategy: Decision Logic for Multiple Parameters

For more complex implementations, you may adapt multiple parameters simultaneously. The following diagram outlines a more sophisticated decision logic that considers both fitness stagnation and population diversity to control both mutation and crossover rates.

Fuzzy Logic Systems for Intelligent, Rule-Based Tuning

Fuzzy Logic (FL) provides a powerful framework for handling uncertainty and imprecision in complex, dynamic systems. In the context of optimizing mutation parameters in Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) and Evolutionary Strategies (ES), FL offers a methodical approach to dynamically balance the critical trade-off between exploration (searching new regions) and exploitation (refining known good areas) [33] [34]. Unlike traditional binary logic, FL operates on a spectrum of truth, using degrees of membership between 0 and 1 to enable reasoning that more closely mirrors human expert decision-making [35] [36] [37].

This technical guide details the implementation of a Fuzzy Logic Part (FLP) for the intelligent, rule-based tuning of mutation size. By using historical data from the evolutionary process, the FLP adjusts mutation parameters in real-time, aiming to improve convergence to a global optimum and enhance resistance to becoming trapped in local optima [33] [34]. The following sections provide a comprehensive technical support framework, including foundational concepts, experimental protocols, and troubleshooting guidance for researchers implementing these systems.

System Architecture and Core Components

A Fuzzy Logic System for parameter tuning transforms crisp, numerical data from the evolutionary process into a controlled output—in this case, a mutation size adjustment. This process occurs through four sequential stages [38] [37].

The Fuzzification Process

The fuzzifier converts precise input values into fuzzy sets by applying Membership Functions (MFs). These functions define how much an input value belongs to a linguistic variable, such as "Low," "Medium," or "High" [37]. Common MF shapes include triangular, trapezoidal, and Gaussian, chosen for their computational efficiency and natural representation of human reasoning [39] [37]. For mutation tuning, inputs like SuccessRate or DiversityIndex are mapped to degrees of membership in these linguistic sets.

Knowledge Base and Fuzzy Rules

The rule base contains a collection of IF-THEN rules formulated by domain experts, encoding strategic knowledge about the evolutionary process [33] [34]. These rules use linguistic variables to describe relationships between observed algorithm states and appropriate control actions.

- Example Rule:

IF SuccessRate IS Low AND DiversityIndex IS Low THEN MutationSizeChange IS LargeIncrease[34]. - Rule Combination: Multiple rules can fire simultaneously, with their outputs combined to determine the final fuzzy output [38].

The Inference Engine

The inference engine evaluates all applicable rules in the rule base against the fuzzified inputs. It determines the degree to which each rule's antecedent (the "IF" part) is satisfied and then applies that degree to the rule's consequent (the "THEN" part). The most common method is max-min inference, where the output membership function is clipped at the truth value of the premise [38].

Defuzzification for Crisp Outputs

The defuzzifier converts the aggregated fuzzy output set back into a precise, crisp value that can be used to adjust the algorithm's mutation size. The centroid method is a popular technique, calculating the center of mass of the output membership function, which provides a balanced output value [38].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow and data flow within the Fuzzy Logic System for mutation tuning:

Key Input Estimators for Mutation Tuning

The performance of the FLP hinges on selecting informative input estimators that accurately reflect the state of the evolutionary process. The following table summarizes critical estimators identified in recent research.

Table 1: Key Input Estimators for Fuzzy Logic-Based Mutation Tuning

| Estimator Name | Description | Linguistic Values (Examples) | Role in Mutation Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Success Rate [33] [34] | Ratio of successful mutations (yielding fitness improvement) to total mutations in a generation. | Very Low, Low, Medium, High | Core input for the 1:5 success rule; low rates may trigger mutation size increases. |

| Population Diversity Index [39] | Measure of genotypic or phenotypic spread within the population (e.g., standard deviation of fitness). | Homogeneous, Medium, Diverse | Low diversity suggests convergence risk, requiring more exploration via larger mutations. |

| Fitness Improvement Trend [33] | Rate of change of best or average fitness over recent generations. | Stagnant, Slow, Fast | Stagnation indicates a need for more exploration (increased mutation). |

| Generational Index [33] | Current generation number normalized by the maximum allowed generations. | Early, Mid, Late | Allows for strategy shift from exploration (early) to exploitation (late). |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing and Validating the FLP

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for implementing the Fuzzy Logic Part for mutation size tuning and validating its performance against standard algorithms.

Phase 1: System Setup and Configuration

Define the Input and Output Variables:

- Inputs: Select at least two estimators from Table 1 (e.g.,

SuccessRateandDiversityIndex). Define their range (universe of discourse) based on preliminary algorithm runs. - Output: Define the

MutationSizeChangevariable, typically as a multiplicative factor (e.g., ranging from 0.5 to 2.0).

- Inputs: Select at least two estimators from Table 1 (e.g.,

Design Membership Functions:

Table 2: Sample Membership Function Definitions for 'SuccessRate'

| Linguistic Term | Membership Function Type | Parameters (a, b, c, d)* |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Trapezoidal | (0.0, 0.0, 0.1, 0.3) |

| Medium | Triangular | (0.1, 0.3, 0.5) |

| High | Trapezoidal | (0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 1.0) |

*Parameters are example values; actual parameters should be calibrated to your specific problem.

- Construct the Fuzzy Rule Base:

- Formulate rules that encapsulate expert strategy. The rule base is the core of the FLP's intelligence.

- Example Rules:

IF SuccessRate IS Low AND DiversityIndex IS Low THEN MutationSizeChange IS LargeIncreaseIF SuccessRate IS High AND DiversityIndex IS High THEN MutationSizeChange IS SmallDecreaseIF GenerationalIndex IS Late AND FitnessTrend IS Stagnant THEN MutationSizeChange IS MediumIncrease

Phase 2: Integration and Execution

Algorithm Integration:

- Embed the FLP into the main loop of your EA or ES, typically after the evaluation step in each generation.

- Use data from the last

Hgenerations (historical data window) to compute the input estimators [33].

Experimental Run:

- Benchmark Functions: Conduct tests on a suite of standard Function Optimization Problems (FOPs) with different characteristics (e.g., unimodal, multimodal, separable, non-separable) [33] [34].

- Comparison: Run the Fuzzy-tuned algorithm alongside a standard EA/ES with fixed or deterministic mutation parameters.

- Metrics: Record key performance metrics for each run (see Table 3).

Phase 3: Performance Validation and Tuning

- Data Collection: For each experiment, log the performance metrics across multiple independent runs to ensure statistical significance.

- System Tuning: The initial FLP setup is a hypothesis. Analyze performance logs to refine membership function parameters and fuzzy rules. Adaptive techniques like ANFIS can automate this tuning [35].

- Validation: Confirm the superiority of the fuzzy-tuned approach by comparing the collected metrics against the baseline algorithms.

The following diagram visualizes this integrated experimental workflow, showing how the FLP interacts with the core evolutionary algorithm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table catalogs essential "research reagents" — the core components and tools needed to build and experiment with a Fuzzy Logic System for parameter tuning.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item / Concept | Function / Purpose | Example Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Linguistic Variable [35] [37] | To represent an input or output parameter using qualitative terms (e.g., "High", "Low") instead of numbers. | Define SuccessRate with terms: Low, Medium, High. Crucial for formulating human-readable rules. |

| Membership Function (MF) [39] [37] | To quantify the degree to which a crisp input value belongs to a linguistic term. | Start with triangular MFs for simplicity. Use trapezoidal MFs for boundary terms. |

| Fuzzy Rule Base [33] [38] | To encode the expert knowledge and control strategy that maps algorithm states to actions. | Keep rules simple and interpretable (e.g., 5-15 rules). Avoid overly complex rule antecedents. |

| Inference Engine [38] | To process the fuzzified inputs by evaluating all fuzzy rules and combining their outputs. | Max-Min inference is a standard and interpretable choice. |

| Defuzzification Method [38] | To convert the fuzzy output set from the inference engine into a single, crisp value for parameter control. | The Centroid (Center-of-Gravity) method is common and produces smooth outputs. |

| Benchmark Function Suite [33] [34] | To provide a standardized and diverse testbed for evaluating algorithm performance. | Use commonly accepted benchmarks (e.g., CEC suites, De Jong functions) for fair comparison. |

| Performance Metrics | To quantitatively compare the performance of different tuning strategies. | Final Best Fitness, Convergence Speed, Robustness (Std. Dev. across runs). |

Performance Metrics and Validation

To quantitatively validate the effectiveness of the fuzzy-tuning approach, compare the following metrics against baseline algorithms across multiple benchmark runs.

Table 4: Key Performance Metrics for Validation

| Metric | Description | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Speed [33] | The number of generations (or function evaluations) required to reach a pre-defined solution quality threshold. | Record the generation number when the best fitness first meets or exceeds the threshold. |

| Solution Quality (Best Fitness) [33] [34] | The value of the best objective function found at the end of the run. | Compare the mean and statistical significance (e.g., via t-test) of the final best fitness. |

| Robustness | The consistency of algorithm performance across different runs and problem instances. | Calculate the standard deviation of the final best fitness across multiple independent runs. |

| Resistance to Local Optima [33] [34] | The algorithm's ability to avoid premature convergence to sub-optimal solutions. | Note the number of runs (out of total) that successfully converge to the global optimum on known multimodal problems. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My fuzzy-tuned algorithm converges slower than the baseline. What could be wrong?

- Incorrect Rule Base: The rules might be overly biased towards exploration (large mutations), preventing refined exploitation. Action: Review and adjust rules to strengthen exploitation actions when

SuccessRateis high andDiversityis acceptable. - Poorly Calibrated Membership Functions: The ranges of your linguistic variables (e.g., what constitutes "Low" success rate) may not match your specific problem. Action: Run preliminary tests with a fixed mutation size to observe typical ranges for your inputs and recalibrate your MFs accordingly [38].

Q2: The algorithm seems to converge prematurely despite the FLP. How can I improve exploration?

- Insufficient Rule Triggering: Rules that increase mutation size may not be firing. Action: Check the activation of your rules during a run. Introduce or strengthen rules that link

Low DiversityandStagnant FitnesstoIncreased Mutation. Ensure your "Low" membership functions correctly capture the states indicating premature convergence. - Historical Data Window Too Small: The FLP might be reacting to very recent trends and missing the bigger picture of stagnation. Action: Increase the size of the historical data window used to compute estimators like

FitnessImprovementTrend[33].

Q3: How do I determine the optimal number of rules and membership functions?

- Start Simple: Begin with a minimal viable system (e.g., 2 inputs with 3 MFs each, leading to 9 possible rules). Overly complex systems are hard to debug and tune. Action: Implement a core set of 5-7 well-designed rules first. You can add more later to handle specific edge cases [38].

- Ensure Coverage: The combination of your MFs should cover the entire "universe of discourse" for each variable without significant gaps to ensure any input value can trigger at least one rule [38].

Q4: My fuzzy system works but is computationally expensive. How can I optimize it?

- Rule Pruning: Analyze which rules fire most frequently. Inactive or rarely used rules can be removed to reduce overhead.

- Caching Strategy: Implement a nearest-neighbor caching (NNC) strategy. Store the input-output pairs and, for new inputs, use a cached result if the input is sufficiently similar to a previous query. This can significantly reduce the number of fuzzy inferences, with one study reporting a speed-up of over 90% [39].

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing genetic algorithms (GAs) for quantum circuit synthesis, focusing specifically on mutation strategy optimization.

Q1: Why does my genetic algorithm converge prematurely to suboptimal quantum circuits?

Premature convergence often indicates insufficient genetic diversity caused by inadequate mutation rates or ineffective mutation strategies. The "delete and swap" mutation combination has demonstrated superior performance by balancing exploration and exploitation [40] [41]. Ensure you're not relying solely on single mutation techniques. Additionally, consider implementing dynamic parameter control approaches like DHM/ILC (Dynamic Decreasing of High Mutation/Dynamic Increasing of Low Crossover), which starts with 100% mutation probability and gradually decreases it while increasing crossover rates throughout the search process [13].

Q2: How do I determine optimal mutation rates for my quantum circuit synthesis problem?

Mutation rates depend on your specific circuit complexity and optimization objectives. For 4-6 qubit circuits, experiments showed that combining multiple mutation strategies outperformed single approaches [40]. For general GA applications, research indicates that dynamic approaches significantly outperform static rates. Consider that DHM/ILC works well with small population sizes, while ILM/DHC (Increasing Low Mutation/Decreasing High Crossover) performs better with larger populations [13]. Static mutation rates of 0.03 with crossover rates of 0.9 represent common baseline values, but dynamic adaptation typically yields better results [13].

Q3: What fitness function components should I prioritize for NISQ device constraints?

For noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices with limited qubits and high error rates, prioritize fidelity while accounting for circuit depth and T operations [40] [42]. The fitness function should balance these competing constraints: fidelity ensures computational accuracy, while minimizing circuit depth and T gates reduces error susceptibility and resource requirements, especially important for fault-tolerant quantum computing [40] [42].

Q4: How do I handle significant parameter drift in quantum systems during optimization?

Quantum systems experience parameter drift on timescales of 10-100 milliseconds, affecting gate fidelity [43]. Implement real-time calibration cycles running at kilohertz rates (at least 10 times faster than drift onset) [43]. The hybrid quantum-classical architecture with reinforcement learning (RL) agents can dynamically optimize multiple parameters during execution, maintaining high fidelity over extended periods by continuously adapting to system changes [43].

Q5: What selection methods work best with mutation strategies for circuit synthesis?

Tournament selection provides a good balance for mutation-intensive approaches due to its efficiency and maintenance of diversity [13]. For quantum circuit synthesis specifically, ensure your selection mechanism doesn't overpower your mutation strategy—the selection pressure should allow promising mutated circuits to propagate without eliminating diversity too quickly. The speciation heuristic can help by penalizing crossover between solutions that are too similar, encouraging population diversity and preventing premature convergence [30].

Key Experiment: Evaluating Mutation Techniques in Quantum Circuit Synthesis

Methodology Overview: Researchers employed a genetic algorithm framework to optimize quantum circuits for 4-6 qubit systems [40]. The experiments utilized a fitness function emphasizing fidelity while accounting for circuit depth and T operations [40]. Comprehensive hyperparameter testing evaluated various mutation strategies, including delete, swap, and their combination [40]. The algorithm evolved populations of candidate circuits through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, with rigorous evaluation against benchmark metrics [40].

Detailed Workflow:

- Initialization: Generate initial population of quantum circuits with random gate sequences

- Evaluation: Calculate fitness for each circuit based on fidelity, depth, and T-count

- Selection: Select parent circuits using tournament selection based on fitness scores

- Genetic Operations: Apply crossover and mutation operators to create offspring

- Replacement: Form new generation through elitism and offspring integration

- Termination Check: Continue until convergence or generation limit reached

Quantitative Results: Mutation Strategy Performance

Table 1: Mutation Strategy Efficacy for Quantum Circuit Synthesis

| Mutation Technique | Circuit Fidelity | Circuit Depth Reduction | T-Count Optimization | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delete Mutation Only | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Acceptable |

| Swap Mutation Only | Moderate | Good | Good | Good |

| Delete + Swap Combination | High | Excellent | Excellent | Best |

Source: Adapted from Kölle et al. (2025) [40]

Table 2: Dynamic Mutation-Crossover Approaches for General GA Applications

| Parameter Strategy | Population Size | Convergence Rate | Solution Quality | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static (0.03 mutation/0.9 crossover) | Large | Moderate | Good | Standard optimization |

| Fifty-Fifty Ratio | Medium | Slow | Variable | Exploration-heavy tasks |

| DHM/ILC (Decreasing High Mutation) | Small | Fast | High | Limited resources |

| ILM/DHC (Increasing Low Mutation) | Large | Fast | High | Complex problems |

Source: Adapted from Information (2019) [13]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Genetic Algorithm-based Quantum Circuit Synthesis

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Circuit Representation | Encodes candidate solutions for evolutionary operations | Gate model, directed acyclic graphs, phase polynomials, ZX diagrams [42] |

| Fitness Function | Evaluates circuit quality based on optimization objectives | Fidelity-centered metric incorporating circuit depth and T operations [40] |

| Selection Operator | Determines which solutions propagate based on quality | Tournament selection maintaining diversity [13] |

| Crossover Operator | Combines elements of parent solutions to create offspring | Multi-point crossover for circuit recombination [44] |

| Mutation Operator | Introduces random variations to maintain diversity and explore new solutions | Delete and swap mutations for quantum gate manipulation [40] |

| Quantum Hardware Interface | Enables real-time execution and calibration on quantum processors | Hybrid architecture with CPU/GPU/QPU integration [43] |

| Decoding System | Interprets measurement outcomes for error correction | Real-time stabilizer measurement processing with <10µs latency [43] |

Genetic Algorithm Workflow for Quantum Circuit Synthesis

Genetic Algorithm Optimization Workflow

Dynamic Parameter Control Strategy

Dynamic Parameter Control Strategy

Key Implementation Recommendations

Based on the mutation strategy evaluation, researchers should prioritize the combined "delete and swap" mutation approach for quantum circuit synthesis, as it consistently outperforms individual mutation techniques [40]. For parameter control, implement dynamic strategies that adapt mutation and crossover rates throughout the evolutionary process rather than maintaining static values [13]. When working under NISQ device constraints, ensure your fitness function appropriately balances fidelity with practical implementation concerns like circuit depth and T-count [40] [42]. Finally, leverage modern hybrid quantum-classical architectures to address system drift and latency requirements, enabling real-time calibration and error correction within the critical 10µs window for effective quantum error correction [43].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does mutation rate in a Genetic Algorithm (GA) influence the search for novel drug targets? An optimal mutation rate is critical for balancing exploration and exploitation. A rate that is too low (e.g., <1%) may cause premature convergence on suboptimal targets, failing to explore the full chemical space. A rate that is too high (e.g., >10%) can turn the search into a random walk, destabilizing potential solutions and preventing the algorithm from refining high-quality candidate targets [45].

Q2: We are using a GA for protein structure prediction. Why does our model perform poorly on multi-domain proteins despite high confidence scores? This is a known limitation of some AI prediction tools. The confidence scores often reflect the accuracy of individual domains but can fail to capture the spatial relationship between domains. Issues like flexible linkers, insufficient evolutionary data for inter-domain interactions in the training set, or a conformation stabilized by crystallization conditions can lead to significant deviations in the relative orientation of domains, causing high Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) values (>7 Å) compared to experimental structures [46].

Q3: What are the key metrics to track when troubleshooting a GA for optimizing lead compounds? Beyond standard metrics like fitness over generations, you should monitor population diversity and selection pressure. A rapid drop in diversity indicates a mutation rate that may be too low. Additionally, use biomedical-specific validation metrics, including Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models for potency, and in-silico predictions for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties to ensure the GA is generating viable, drug-like molecules [47] [48].

Q4: Can GAs be integrated with other AI methods like AlphaFold in a drug discovery pipeline? Yes, this is a powerful hybrid approach. GAs can be used to generate and optimize novel amino acid sequences or drug-like molecules. These generated sequences can then be fed into protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold to validate their foldability and predicted 3D structure. This combined workflow accelerates the design-make-test cycle for de novo protein design or drug candidate optimization [49] [50].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Performance in Imbalanced Data Classification for Drug-Target Interaction

- Symptoms: The GA-based model exhibits high accuracy but poor recall for the minority class (e.g., active compounds), failing to identify true positive interactions.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The fitness function is biased towards the majority class.

- Solution: Redesign the fitness function to use metrics like F1-score or AUC-ROC, which are more robust to class imbalance. Research shows that using Logistic Regression or Support Vector Machines to define the fitness function can significantly improve minority class representation [45].

- Cause: The initial population lacks sufficient diversity in the minority class.

- Solution: Apply specialized synthetic data generation techniques like the Genetic Algorithm-based approach, which has been shown to outperform SMOTE and ADASYN in imbalanced biomedical datasets. This method creates synthetic minority class samples optimized through a fitness function to enhance model performance [45].

- Cause: The fitness function is biased towards the majority class.

Problem 2: Suboptimal Mutation Rate Leading to Stagnation or Divergence

- Symptoms: The algorithm's fitness plateaus early (stagnation) or fails to converge, producing erratic results (divergence).

- Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Monitor Diversity: Track the genotypic diversity of the population over generations. A rapid decrease suggests stagnation.

- Adjust Mutation Rate Adaptively:

- For Stagnation, implement an adaptive strategy that slightly increases the mutation rate when a lack of diversity is detected.

- For Divergence, reduce the mutation rate. A good starting point is typically between 1% and 5%.

- Test Protocol: Run the GA 10 times with a fixed, low mutation rate (1%) and 10 times with a fixed, high rate (10%). Compare the average best fitness over 100 generations. The optimal rate is one that finds a stable, high-fitness solution. The Elitist GA variant, which preserves top performers, can also help mitigate these issues [45].

Problem 3: Inaccurate Inter-Domain Protein Structure Prediction

- Symptoms: The predicted protein model has high local confidence (pLDDT) for individual domains but shows significant positional divergence (>30 Å) for equivalent residues in the global scaffold compared to experimental data [46].

- Action Plan: