Orthogroup Analysis for Evolutionary Studies: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Biomedical Applications

Orthogroup analysis has become a cornerstone of modern comparative genomics, enabling researchers to trace gene evolution across species and identify functionally significant genes.

Orthogroup Analysis for Evolutionary Studies: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

Orthogroup analysis has become a cornerstone of modern comparative genomics, enabling researchers to trace gene evolution across species and identify functionally significant genes. This article provides a comprehensive guide to orthogroup analysis, covering foundational concepts of orthology and paralogy, step-by-step methodologies using leading tools like OrthoFinder, best practices for troubleshooting and optimizing analyses with complex genomes, and rigorous validation techniques. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we synthesize current benchmarks and real-world case studies to demonstrate how accurate orthology inference can illuminate evolutionary history, identify lineage-specific adaptations, and prioritize candidate genes for therapeutic development.

Orthology Fundamentals: Deciphering Gene Evolutionary Relationships for Comparative Genomics

In comparative genomics, accurately classifying gene relationships is fundamental to understanding evolutionary processes, gene function, and phenotypic diversity. Homology—the concept that biological features share common ancestry—forms the bedrock of this classification system [1]. Homologous genes arise from a common ancestor but have diverged through evolutionary mechanisms, primarily speciation and gene duplication events. These divergence pathways create distinct relationship categories with different implications for functional prediction and evolutionary analysis. Orthologs are genes separated by speciation events—when a species diverges into two separate species, the descendant copies of a single gene in the two resulting lineages are orthologous [1] [2]. Paralogs are genes separated by gene duplication events—when a gene duplicates within a genome, the resulting copies are paralogous [1] [2]. An orthogroup represents the complete set of genes descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor of all species being considered, encompassing both orthologs and paralogs [3]. These concepts provide the foundational framework for orthogroup analysis in evolutionary studies, enabling researchers to trace gene evolution across species boundaries and through deep evolutionary time.

Core Concepts: Distinguishing Orthologs, Paralogs, and Orthogroups

Defining Characteristics and Evolutionary Origins

The classification of gene relationships requires understanding their evolutionary origins. Orthologs originate via speciation events, where a single gene in an ancestral species gives rise to descendant genes in two daughter species [1]. These genes typically retain the same function as their ancestor through vertical descent, making them particularly valuable for functional annotation transfer across species [4]. Paralogs originate via gene duplication events within a lineage, creating additional gene copies that may evolve new functions (neofunctionalization) or partition ancestral functions (subfunctionalization) [2]. This functional divergence among paralogs represents a crucial mechanism for evolutionary innovation and increased biological complexity.

Orthogroups provide a comprehensive framework for classifying gene relationships across multiple species by representing all genes descended from a single ancestral gene in the last common ancestor of the species under consideration [3]. This concept logically extends orthology and paralogy to multiple species, recognizing that an orthogroup by definition contains both orthologs and paralogs [3]. Walter Fitch's pioneering work clarified that orthology and paralogy are properties of gene pairs rather than individual genes, and that these relationships can be determined by tracing genes back to their point of divergence—an inverted "Y" (speciation) for orthologs or a horizontal line (duplication) for paralogs [4].

Common Misconceptions and Clarifications

Several persistent misconceptions complicate proper usage of these terms. First, paralogs are not necessarily restricted to the same genome; they may exist in different species following speciation events that occur after gene duplication [4]. Second, orthology and paralogy should not be defined based on functional similarity; while orthologs often conserve function, they can acquire new functions, and paralogs sometimes retain similar functions [4]. Third, sequence similarity alone does not establish homology; statistically significant sequence similarity suggests homology, but homologous sequences do not always share significant similarity due to divergent evolution [5] [2]. Finally, the terms "percent homology" and "sequence similarity" are not interchangeable—homology is a binary state (sequences are either homologous or not), while similarity is a quantitative measure [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Gene Relationship Types

| Relationship Type | Evolutionary Origin | Functional Implications | Typical Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthologs | Speciation event | Often retain ancestral function; reliable for functional annotation transfer | Different species |

| Paralogs | Gene duplication event | May evolve new functions or partition ancestral functions; source of evolutionary innovation | Same or different species |

| Orthogroup | Last common ancestor of all considered species | Contains all descendants including both orthologs and paralogs; unit for comparative genomics | Multiple species |

Computational Methods for Orthology Inference

Algorithmic Approaches and Methods

Computational methods for inferring orthology relationships have evolved from simple pairwise comparisons to sophisticated phylogenetic approaches. Early methods relied heavily on the Reciprocal Best Hit (RBH) approach, where two genes in different species are considered orthologs if each is the best match of the other in pairwise sequence comparisons [6]. While RBH has high precision, it suffers from low recall in detecting complete orthogroups, particularly when gene duplications create complex relationships [3]. The OrthoMCL algorithm addressed some limitations by applying the Markov Cluster Algorithm (MCL) to sequence similarity graphs, identifying highly-connected clusters of genes [3]. However, this approach demonstrated significant gene length bias, where short sequences showed low recall (missing assignments) and long sequences showed low precision (incorrect assignments) [3].

More recent methods like OrthoFinder implement novel solutions to these challenges. OrthoFinder employs a length normalization transform that eliminates gene length bias by modeling the relationship between BLAST bit scores and sequence length for each species pair independently [3]. This transformation ensures that scoring thresholds are equitable across genes of different lengths, dramatically improving both precision and recall [3]. The updated OrthoFinder algorithm implements a comprehensive phylogenetic approach that infers gene trees for all orthogroups, reconstructs the rooted species tree, identifies gene duplication events, and determines orthologs using duplication-loss-coalescence (DLC) analysis [7]. This method has demonstrated 3-30% higher accuracy compared to other approaches on standard benchmarks [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Orthology Inference Methods

| Method | Algorithmic Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBH (Reciprocal Best Hit) | Pairwise sequence comparison | High precision for simple cases | Low recall; fails with gene duplications |

| OrthoMCL | MCL clustering of similarity graphs | Handles multiple species; widely used | Strong gene length bias; lower accuracy |

| DomClust | Hierarchical clustering (UPGMA) with domain splitting | Detects domain fusion/fission events | Complex implementation |

| OrthoFinder | Phylogenetic tree-based with length normalization | Highest accuracy; comprehensive output | Computationally intensive for very large datasets |

OrthoFinder Workflow and Implementation

The OrthoFinder algorithm implements a sophisticated multi-step process for orthology inference. The workflow begins with orthogroup inference using length-normalized similarity scores derived from all-vs-all sequence comparisons [3]. Next, gene trees are inferred for each orthogroup, typically using fast phylogenetic methods like DendroBLAST [7]. These gene trees are then analyzed to infer the rooted species tree without prior knowledge of species relationships [7]. The rooted species tree subsequently enables accurate rooting of all gene trees, which is essential for proper interpretation [7]. Finally, duplication-loss-coalescence analysis of the rooted gene trees identifies orthologs and gene duplication events, mapping them to both gene trees and species trees [7].

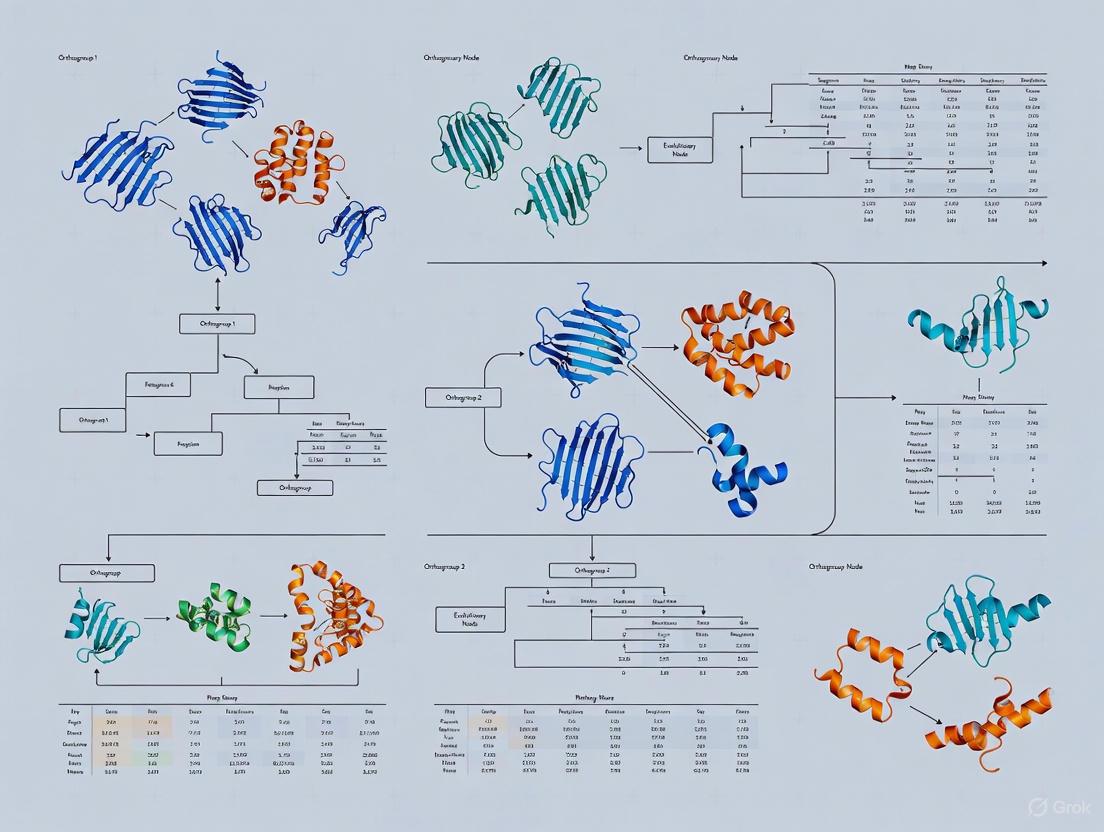

Figure 1: OrthoFinder phylogenetic orthology inference workflow illustrating the key steps from sequence input to comprehensive ortholog identification.

Experimental Protocols for Orthogroup Analysis

OrthoFinder Protocol for Orthogroup Inference

OrthoFinder provides a standardized protocol for orthogroup inference that balances accuracy with computational efficiency. The following protocol details the essential steps:

Step 1: Software Installation OrthoFinder can be installed via Conda for simplified dependency management:

Step 2: Input Data Preparation Prepare protein sequence files in FASTA format for each species to be analyzed. Use consistent naming conventions and ensure sequences represent the complete proteome for optimal results. For genome annotations in GFF/GTF format, first extract protein sequences using tools like AGAT or BEDTools.

Step 3: Running OrthoFinder Execute OrthoFinder with default parameters for most applications:

Where -t specifies the number of threads for BLAST/DIAMOND searches and -a specifies the number of threads for orthogroup inference. For large datasets (dozens of species), consider using DIAMOND instead of BLAST for significantly faster execution:

Step 4: Results Interpretation OrthoFinder generates numerous output files in a structured directory. Key outputs include:

Orthogroups.tsv: The core orthogroup assignmentsOrthogroups_UnassignedGenes.tsv: Genes not assigned to orthogroupsOrthogroups.GeneCount.tsv: Count matrix of genes per orthogroup per speciesComparative_Genomics_Statistics/: Directory containing various statisticsGene_Trees/: Inferred gene trees for each orthogroupResolved_Gene_Trees/: Rooted gene trees after analysis

Pan-genome Analysis Protocol

Orthogroup analysis forms the foundation for pan-genome studies, which classify genes based on their distribution across individuals:

Step 1: Orthogroup Presence/Absence Matrix

Convert OrthoFinder output to a binary matrix indicating orthogroup presence (1) or absence (0) in each genome. This can be accomplished using the Orthogroups.GeneCount.tsv file and custom R or Python scripts.

Step 2: Gene Category Assignment Classify genes into four pan-genome categories based on presence frequency across genomes using these standard thresholds:

- Core genes: Present in 100% of genomes (frequency = 1.0)

- Softcore genes: Present in ≥95% but <100% of genomes (frequency ≥ 0.95)

- Dispensable genes: Present in more than one but <95% of genomes (1 < count < 0.95N)

- Private genes: Present in only one genome (count = 1)

Step 3: Statistical Analysis in R Implement the following R code to assign gene categories:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Ortholog and Orthogroup Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Phylogenetic orthology inference | Genome-wide orthogroup identification | High accuracy; comprehensive outputs; species tree inference |

| DIAMOND | Accelerated sequence similarity search | Large-scale BLAST-like searches | 1000x-20,000x faster than BLAST; sensitive |

| OrthoMCL | Graph-based orthogroup clustering | Orthogroup identification from BLAST results | Widely used; handles large datasets |

| OMA | Pairwise orthology inference | Precise ortholog pairs between species | High precision; hierarchical orthogroups |

| PANTHER | Curated ortholog database | Functional annotation and evolution | Manual curation; phylogenetic trees |

| EggNOG | Orthology database and functional annotation | Functional evolutionary genomics | Functional annotations; COG categories |

| DL-Norepinephrine hydrochloride | DL-Norepinephrine hydrochloride, CAS:55-27-6, MF:C8H12ClNO3, MW:205.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 1-(6-Methoxy-2-naphthyl)ethanol | 1-(6-Methoxy-2-naphthyl)ethanol, CAS:77301-42-9, MF:C13H14O2, MW:202.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Evolutionary Studies and Drug Development

Evolutionary Inferences from Orthogroup Analysis

Orthogroup analysis enables numerous evolutionary inferences that extend beyond simple gene classification. The distribution of gene categories in pan-genome analyses reveals fundamental evolutionary processes. Core genes typically encode essential cellular functions like DNA replication, transcription, translation, and metabolic pathways [8]. These genes experience strong purifying selection that maintains their sequence and function across evolutionary time. Softcore genes represent conserved components with some population-specific variability, often involved in environmental interactions [8]. Dispensable genes drive phenotypic diversity and adaptation, frequently enriched for functions in stress response, immunity, and secondary metabolism [8]. Private genes may represent recent acquisitions through horizontal gene transfer or de novo formation, though they require careful validation to distinguish from annotation artifacts [8].

Orthogroup analysis also enables the identification of gene family expansions and contractions through comparative analysis of orthogroup sizes across species. Lineage-specific expansions of paralogous genes often correspond to adaptive innovations—for example, the expansion of olfactory receptor genes in mammals or detoxification enzymes in insects. Conversely, gene family contractions may indicate relaxed selective constraints or functional shifts. By mapping orthogroup size variations to phylogenetic trees, researchers can reconstruct the evolutionary history of gene families and identify potential correlations with phenotypic evolution.

Implications for Drug Development and Target Identification

Orthology analysis has profound implications for drug development, particularly in target identification and validation. Orthologs often conserve function across species, making animal model studies more predictive of human biology [7]. When a drug target is identified in model organisms, analyzing its orthologs in humans provides critical insights for translational research. Conversely, identifying paralogs is equally important because they may have diverged in function, creating potential for selective targeting—drugs can be designed to specifically target pathogenic paralogs while sparing human orthologs.

The orthogroup concept further assists in drug development by identifying entire gene families with related functions. For example, analyzing kinase or GPCR orthogroups across species reveals both conserved binding sites (enabling broad-spectrum drug design) and divergent regions (allowing species-specific targeting). In antimicrobial drug development, comparing pathogen core genes to human orthologs identifies essential pathogen processes that differ from human biology, revealing promising drug targets with minimal host toxicity. Pan-genome analysis of pathogen populations further distinguishes core genes (potential broad-spectrum targets) from dispensable genes (indicators of strain-specific adaptations) [8].

Figure 2: Drug target identification workflow using orthology analysis to select targets with optimal specificity and safety profiles.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integrating Orthology with Structural and Functional Data

Contemporary orthology inference increasingly integrates multiple data types beyond sequence similarity. Structural orthology—inferring relationships based on protein structure—can reveal homologous relationships that are undetectable at the sequence level, particularly for rapidly evolving proteins or very deep evolutionary relationships [5]. Functional data from high-throughput experiments (e.g., gene expression patterns, protein-protein interactions, genetic interactions) provide orthogonal evidence for validating orthology predictions. The emerging field of phylogenomics continues to develop integrated approaches that leverage genomic context, synteny conservation, and functional genomics data to refine orthology inferences.

Machine learning approaches represent a promising frontier for orthology prediction, potentially capable of integrating diverse data types and learning complex patterns that distinguish orthologs from paralogs. These methods could address challenging cases like horizontal gene transfer, which creates xenologs—homologs separated by horizontal transfer events—that complicate straightforward orthology/paralogy classifications. As multi-omics data become increasingly available, the integration of evolutionary relationships with functional genomics will enable more accurate prediction of gene function and more sophisticated models of genome evolution.

Validation and Benchmarking of Orthology Predictions

Validating orthology predictions remains challenging due to the lack of comprehensive ground truth data. The Quest for Orthologs consortium maintains benchmark datasets and standardized assessments to objectively evaluate orthology inference methods [7]. These benchmarks use various criteria including agreement with curated gene trees, functional consistency, and phylogenetic discordance tests. OrthoFinder consistently ranks among the top performers on these benchmarks, achieving 3-24% higher accuracy than other methods on tree-based tests [7].

For individual research projects, several strategies can validate orthology inferences. Statistical significance testing using shuffled sequences confirms that alignment scores exceed random expectations [5]. Independent validation can include assessing whether putative orthologs share similar domain architectures, gene structures, and genomic contexts. Functional validation through experimental approaches—such as cross-species complementation assays—provides the strongest evidence for orthology, though at substantially greater cost and effort. For well-studied gene families, comparison to manually curated phylogenetic trees in databases like TreeFam or PhylomeDB offers additional validation.

The Critical Role of Orthology in Species Phylogeny Reconstruction and Functional Annotation

Orthology, a concept formalized by Walter Fitch, describes genes in different species that originated from a single ancestral gene through a speciation event [9]. This evolutionary relationship stands in contrast to paralogy, where genes originate from gene duplication events within a lineage [9]. The precise delineation of orthologous relationships is fundamental to comparative genomics, serving as the cornerstone for two primary research domains: the reconstruction of species phylogenies and the functional annotation of genomes [9]. The critical "orthology-function conjecture" posits that orthologous genes typically retain equivalent biological functions across different organisms, enabling the transfer of functional annotations from characterized genes in model organisms to their uncharacterized orthologs in newly sequenced genomes [9].

The process of orthology inference has evolved significantly with the advent of large-scale genomic sequencing. Modern methods must navigate complex evolutionary scenarios involving lineage-specific gene duplications, losses, and horizontal gene transfers, which create intricate relationships beyond simple one-to-one correspondences [9]. These include one-to-many and many-to-many orthology relationships, requiring the use of specialized terms such as co-orthologs, in-paralogs, and out-paralogs to accurately describe the evolutionary history of gene families [9]. The accurate resolution of these relationships is not merely a taxonomic exercise but a prerequisite for reliable downstream biological analyses.

Orthology Inference Methodologies and Tools

Phylogenetic Tree-Based Approaches

Tree-based methods for orthology inference leverage phylogenetic trees to delineate evolutionary relationships among genes. These methods typically involve reconstructing gene trees and then reconciling them with the species tree to identify speciation nodes (indicating orthologs) and duplication nodes (indicating paralogs) [10]. The LOFT (Levels of Orthology From Trees) tool implements the "levels of orthology" concept, which uses a hierarchical numbering scheme to describe multi-level gene relations that naturally arise from phylogenetic trees [10]. This approach effectively captures the non-transitive nature of orthology, where genes from groups 3.1.1 and 3.1.2 might both be orthologous to genes in group 3.1, yet paralogous to each other [10].

LOFT can employ two different strategies to identify speciation and duplication events: (1) classical species-tree reconciliation, where a trusted species phylogeny is mapped onto the gene tree, or (2) a species overlap rule, where a node is considered a speciation event if its branches have mutually exclusive sets of species [10]. Benchmark studies have demonstrated that the species overlap rule performs remarkably well despite its simplicity, showing high correlation with gene-order conservation, a reliable indicator of functional equivalence [10].

Scalable Algorithmic Frameworks

To address the computational challenges posed by ever-increasing genomic datasets, several scalable orthology inference tools have been developed:

OrthoFinder represents a major advance in phylogenetic orthology inference, extending beyond simple orthogroup identification to provide comprehensive phylogenetic analysis [7]. Its algorithm involves: (1) orthogroup inference, (2) gene tree inference for each orthogroup, (3) analysis of gene trees to infer the rooted species tree, (4) rooting of gene trees using the species tree, and (5) duplication-loss-coalescence analysis to identify orthologs and gene duplication events [7]. On benchmark tests, OrthoFinder demonstrates 3-24% higher accuracy on SwissTree and 2-30% higher accuracy on TreeFam-A compared to other methods, making it the most accurate ortholog inference method available [7].

FastOMA addresses the critical challenge of scalability in orthology inference, enabling the processing of thousands of eukaryotic genomes within a day while maintaining high accuracy [11]. This represents a significant improvement over traditional OMA and other methods like OrthoFinder and SonicParanoid, which exhibit quadratic time complexity [11]. FastOMA achieves linear scalability through a two-step process: (1) fast gene family inference using k-mer-based placement with OMAmer and clustering of unplaced sequences with Linclust, and (2) taxonomy-guided inference of the nested structure of Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) via a leaf-to-root traversal of the species tree [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Orthology Inference Tools

| Tool | Methodology | Key Features | Accuracy (SwissTree Benchmark) | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Phylogenetic tree-based | Infers orthogroups, gene trees, species trees, and duplication events | Highest accuracy (F-score) [7] | Quadratic time complexity [11] |

| FastOMA | Graph-based with hierarchical grouping | Linear scaling, handles fragmented genes and isoforms | Precision: 0.955, Recall: 0.69 [11] | Linear time complexity [11] |

| LOFT | Tree-based with level numbering | "Levels of orthology" concept, hierarchical numbering | High correlation with gene-order conservation [10] | Dependent on tree size and complexity |

Experimental Protocols for Orthology Analysis

Standard Orthology Inference Workflow Using OrthoFinder

Protocol: Comprehensive Orthology Analysis with OrthoFinder

Input Requirements:

- Protein sequences in FASTA format for all species of interest

- Each species' sequences should be in a separate file

- Sequence headers should be consistent within and across files

Procedure:

- Software Installation

- Install OrthoFinder via GitHub:

git clone https://github.com/davidemms/OrthoFinder - Ensure dependencies are installed: Python 3, DIAMOND, MCL, FastME, MAFFT

- Install OrthoFinder via GitHub:

Running OrthoFinder

- Basic execution:

orthofinder -f [path_to_protein_files] - For large datasets, use DIAMOND for accelerated sequence search:

orthofinder -f [path] -S diamond - To use specific multiple sequence alignment and tree inference tools:

orthofinder -f [path] -M msa -A mafft -T iqtree

- Basic execution:

Output Analysis

- Orthogroups: Located in

Orthogroups.csv - Orthologs: Species-specific orthologs in

Orthologues_[date]directory - Gene trees: Rooted gene trees for each orthogroup in

Resolved_Gene_Trees - Species tree: Inferred species tree in

SpeciesTree_rooted.txt - Comparative genomics statistics: Various statistics in

Comparative_Genomics_Statistics

- Orthogroups: Located in

Troubleshooting:

- For memory issues with large datasets, use

-toption to specify number of threads - If gene trees are inaccurate, consider using more precise alignment tools

- For discordance between gene trees and species tree, investigate potential incomplete lineage sorting

Large-Scale Orthology Inference with FastOMA

Protocol: Scalable Orthology Analysis for Genome-Scale Datasets

Input Requirements:

- Proteome sets for all species of interest in FASTA format

- Species tree in Newick format (optional; NCBI taxonomy used by default)

Procedure:

- Software Setup

- Install FastOMA from GitHub:

git clone https://github.com/DessimozLab/FastOMA/ - Install dependencies: OMAmer, Linclust (from MMseqs2 package)

- Install FastOMA from GitHub:

Execution Steps

- Run FastOMA with default settings:

fastoma -i [input_dir] -o [output_dir] - To specify a custom species tree:

fastoma -i [input_dir] -o [output_dir] -t [species_tree.nwk] - For handling fragmented gene models:

fastoma -i [input_dir] -o [output_dir] --handle-fragments

- Run FastOMA with default settings:

Output Interpretation

- Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs): Nested orthology assignments at different taxonomic levels

- RootHOGs: Core gene families at the root level

- Orthology relationships: Pairwise orthologs and paralogs

- Gene evolutionary history: Patterns of gene duplication and loss

Performance Optimization:

- Use 300 CPU cores for processing 2,000+ eukaryotic proteomes within 24 hours

- For smaller datasets, adjust core usage accordingly

- Pre-cluster sequences using OMAmer for accelerated processing

Research Reagent Solutions for Orthology Analysis

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for Orthology Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthology Inference Software | OrthoFinder, FastOMA, LOFT | Identify orthologs and paralogs from sequence data | Large-scale comparative genomics, phylogenomics |

| Sequence Databases | OMA Database, OrthoDB, Ensembl Compara | Provide pre-computed orthology relationships | Functional annotation, evolutionary studies |

| Alignment Tools | MAFFT, PRANK, Clustal-Omega | Generate multiple sequence alignments | Gene tree inference, sequence evolution analysis |

| Phylogenetic Software | IQ-TREE, RAxML, FastME | Infer phylogenetic trees from sequences | Gene tree and species tree reconstruction |

| Benchmarking Resources | Quest for Orthologs (QfO) | Standardized assessment of orthology methods | Method validation, tool selection |

Applications in Evolutionary Genomics and Functional Annotation

Species Phylogeny Reconstruction

Orthologous genes provide the true signal for reconstructing species evolutionary histories because they reflect the divergence of species through speciation events [9]. Using paralogous genes for this purpose would confound the evolutionary history with gene duplication events, leading to inaccurate phylogenetic inferences. The process involves:

- Identification of single-copy orthologs present in all species under study

- Multiple sequence alignment of each orthologous gene set

- Individual gene tree inference using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods

- Species tree reconstruction from multiple gene trees using coalescent-based or concatenation approaches

OrthoFinder automates much of this process by directly inferring the rooted species tree from the complete set of gene trees, providing a robust phylogenetic framework for downstream analyses [7]. This approach has been shown to produce highly accurate species trees that reliably reflect evolutionary relationships.

Functional Annotation and Annotation Transfer

The "orthology-function conjecture" enables the transfer of functional information from experimentally characterized genes to their orthologs in other species [9]. This application is fundamental to making biological sense of the thousands of newly sequenced genomes. The protocol for reliable functional annotation transfer includes:

- Identification of orthologs using robust phylogenetic methods

Assessment of functional divergence through:

- Analysis of domain architecture conservation [9]

- Examination of gene context and synteny conservation

- Evaluation of selective pressure using dN/dS ratios

Experimental validation of key functional predictions when possible

A critical consideration is that the genocentric definition of orthology becomes problematic when homologous proteins have different domain architectures [9]. In such cases, orthology relationships may need to be established at the domain level rather than the gene level for accurate functional inference.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, orthology inference still faces several challenges that represent active research areas:

Systematic Errors: Methodological biases in orthology inference can propagate to downstream evolutionary analyses, potentially leading to incorrect biological conclusions [12]. Different orthology inference methods can produce systematically different results, affecting comparative genomic studies.

Unit of Orthology: The traditional gene-centered view of orthology is increasingly recognized as insufficient, particularly in eukaryotes where alternative splicing and complex domain architectures create proteins with multiple functional units [9]. Future methods may need to operate at the domain or even smaller evolutionary units.

Scalability: With initiatives aiming to sequence 1.5 million eukaryotic species, scalability remains a critical concern [11]. While tools like FastOMA represent significant advances, continued innovation is needed to handle the coming data deluge.

Integration of Additional Evidence: Future orthology methods will likely incorporate structural information, gene order conservation, and other genomic features to improve accuracy, particularly for deep evolutionary relationships where sequence similarity is low [11].

The continued development of orthology inference methods, benchmark resources like the Quest for Orthologs, and community standards ensures that orthology analysis will remain a cornerstone of comparative genomics and evolutionary biology, enabling researchers to trace the history of life through the evolutionary history of genes.

In evolutionary genomics, homology describes the relationship between genes originating from a common ancestor. This broad relationship is categorized into specific subtypes, with orthology and paralogy being fundamental. Orthologs are genes related by speciation events, while paralogs are genes related by duplication events [13] [14]. Accurately distinguishing between these relationships is critical for reliable inference of species phylogenies and functional gene annotation, as orthologs often retain similar functions across species [13].

The concepts of co-orthology and in-paralogy further refine these relationships. These are defined relative to a specific speciation event and describe complex family histories involving duplications. Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) provide a structured framework to represent these relationships across multiple taxonomic levels, offering a practical solution for comparative genomic analyses [15] [13]. This article details the definitions, inference protocols, and applications of these concepts within the OMA (Orthologous MAtrix) framework, providing a guide for researchers in evolutionary studies and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Defining the Relationships

Core Definitions and Terminology

The following terms form the foundational vocabulary for understanding complex orthologous relationships [14]:

- Orthology: A relationship between a pair of homologous genes that originated due to a speciation event.

- Paralogy: A relationship between a pair of homologous genes that originated due to a gene duplication event.

- In-Paralogy: A relationship defined over a triplet, involving a pair of genes and a speciation event of reference. Two genes are in-paralogs if they are paralogs and the duplication event occurred after the specified speciation event.

- Out-Paralogy: A relationship where the duplication event through which two genes are related predates the speciation event of reference.

- Co-orthology: A relationship defined over three genes, where two of them are in-paralogs with respect to the speciation event associated with the third (outgroup) gene. These two in-paralogous genes are said to be co-orthologous to the third gene.

Table 1: Summary of Key Orthology and Paralogy Relationships

| Relationship | Defining Event | Key Characteristic | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthology | Speciation | Genes in different species descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor [13]. | High functional conservation; ideal for species tree inference and functional annotation transfer [13]. |

| Paralogy | Duplication | Genes in the same or different species descended from a duplicated ancestral gene [14]. | Potential for functional diversification (neo- or sub-functionalization). |

| In-Paralogy | Duplication (post-speciation) | Paralogs that duplicated after a given speciation event [14]. | Represents lineage-specific expansions; co-orthologs can have redundant or specialized functions. |

| Out-Paralogy | Duplication (pre-speciation) | Paralogs that duplicated before a given speciation event [14]. | Represents ancient duplications; functional divergence is more likely. |

Visualizing Evolutionary Relationships and HOGs

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships between these concepts in an evolutionary tree and the corresponding data structure of a HOG.

Diagram 1: Evolutionary gene tree showing orthologs, paralogs, and co-orthologs. S1 and S2 are speciation events; D1 is a duplication event. Genes x1 and y1 are one-to-one orthologs. Genes x1 and x2 are in-paralogs with respect to S2. Genes x1 and y2 are out-paralogs with respect to S2. Genes x1 and x2 are co-orthologs with respect to z1 [14].

Diagram 2: Hierarchical structure of HOGs. A root HOG contains all descendants of an ancestral gene. At each taxonomic level (e.g., Vertebrate, Mammalian, Primate), the HOG is subdivided, reflecting duplications. At the primate level, a duplication event splits the mammalian HOG into two separate primate-level HOGs, B1 and B2 [15] [13].

Orthology Inference and HOG Construction in OMA

Protocol: OMA Orthology Inference Workflow

This protocol describes the step-by-step process used by the OMA algorithm to infer pairwise orthologs and construct HOGs [13].

Input Materials:

- Proteomes: Amino acid sequences for all species of interest in FASTA format.

- Species Tree: A phylogenetic tree representing the known evolutionary relationships among the input species.

Procedure:

- All-against-All Alignment: Perform a pairwise alignment of every protein in every proteome against every other protein to identify potential homologous sequences.

- Pairwise Ortholog Inference: For each pair of genomes, identify putative orthologs by filtering out out-paralogs while retaining in-paralogs. This step produces a list of pairwise orthologous relationships, each with a cardinality (1:1, 1:m, m:m) [15] [13].

- Construct Orthology Graph: Map the pairwise orthologs to a graph structure.

- Nodes: Represent individual genes.

- Edges: Represent inferred pairwise orthologous relationships between genes.

- Graph Cleaning: Identify and remove spurious edges (incorrect pairwise inferences) from the orthology graph to improve accuracy.

- Form Connected Components: Identify all connected components in the cleaned graph. Each connected component represents a putative gene family descended from a single ancestral gene.

- Build Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs):

- Traverse the species tree from the leaves (extant species) towards the root.

- At each taxonomic level (e.g., primates, mammals, vertebrates), group genes into a HOG if they descended from a single gene in the ancestor of that taxonomic level [15] [13].

- This results in a nested hierarchy of groups, where HOGs at recent clades are subsets of larger HOGs at older clades.

Outputs:

- A list of pairwise orthologs with relationship cardinalities.

- Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) defined at various taxonomic levels.

- OMA Groups, which are cliques (fully connected subgraphs) of orthologs from the orthology graph [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Orthology Inference

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Orthogroup Analysis

| Resource/Tool | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| OMA Browser [15] [13] | Database & Web Interface | Publicly accessible resource for querying pre-computed orthologs, HOGs, and OMA Groups across >2000 species. |

| FastOMA [11] | Software Algorithm | Scalable orthology inference tool for analyzing large-scale genomic datasets (thousands of genomes) with linear time complexity. |

| OMAmer [11] | Software Tool | Alignment-free tool for rapidly placing new protein sequences into pre-defined root HOGs using k-mers, used within the FastOMA pipeline. |

| NCBI Taxonomy [11] | Database | Reference taxonomy used by default in orthology inference to guide the species tree structure for HOG construction. |

| Species-specific Proteomes (e.g., from UniProt) | Data | Curated protein sequence sets for each species, serving as the primary input for the orthology inference pipeline. |

Application Notes for Evolutionary Analyses

Choosing the Right Type of Orthologs for Your Analysis

Different research questions require different types of orthology data. The table below guides selecting the appropriate data structure from OMA.

Table 3: Guide to Selecting Orthology Data Types in OMA

| Research Goal | Recommended Data Type | Rationale | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotation Transfer | Pairwise Orthologs (1:1) | 1:1 orthologs show the highest degree of functional conservation, making them most reliable for transferring functional annotations between two specific species [13]. | Inferring the function of a newly sequenced mouse gene based on its 1:1 human ortholog. |

| Phylogenomic Profiling / Gene Presence-Absence | HOGs | HOGs provide a stable evolutionary unit across broad taxonomic ranges, allowing for consistent profiling of gene gains and losses in a lineage [13] [11]. | Profiling the evolutionary history of a gene family across eukaryotes to identify lineage-specific losses. |

| Analyzing Gene Duplication History | HOGs | The hierarchical structure of HOGs explicitly models duplication events at different taxonomic levels, making them ideal for studying the history of gene families [15] [13]. | Determining whether a duplication event in a gene family occurred before or after the radiation of mammals. |

| Species Tree Inference | OMA Groups | OMA Groups are cliques of orthologs where all members are mutually orthologous, minimizing the risk of including paralogs that could confound species tree reconstruction [15] [13]. | Constructing a robust species phylogeny using concatenated sequences of universal, single-copy orthologs. |

| Identifying Co-orthologs / In-paralogs | HOGs (at specific taxonomic levels) | HOGs defined at the level just after a duplication event will contain the co-orthologous copies. The in-paralogs are the genes within the same species in that HOG [14]. | Finding all human genes that are co-orthologous to a single Drosophila gene following a lineage-specific duplication in primates. |

Protocol: Identifying Co-orthologs and In-paralogs Using the OMA Browser

This protocol provides a practical method for researchers to find co-orthologs and in-paralogs for a gene of interest.

Objective: To identify all human co-orthologs and in-paralogs of a specific mouse gene using HOGs.

Procedure:

- Access the OMA Browser: Navigate to https://omabrowser.org [13].

- Search for Your Gene: In the search bar, enter the gene identifier (e.g., "TP53") or protein sequence and select the species of origin (e.g., Mus musculus) from the results.

- Navigate to the HOG View: On the gene page, locate and click the "Hierarchical Orthologous Groups" or "HOG" section/tab.

- Select the Relevant Taxonomic Level: The browser will display the HOGs containing your gene at different taxonomic levels. Identify the HOG defined at the last common ancestor of your species of interest. For example, to find human co-orthologs of a mouse gene, select the HOG at the "Euarchontoglires" or "Boreoeutheria" level, which is the common ancestor of mice and humans.

- Identify Co-orthologs and In-paralogs:

- Co-orthologs: All genes from the target species (e.g., human) within the selected HOG are co-orthologous to your query gene (e.g., mouse). If the mouse gene has in-paralogs, all human genes in the HOG are co-orthologous to all mouse genes in the HOG [14].

- In-paralogs: Within the HOG, all genes from the same species (e.g., multiple human genes) that resulted from a duplication after the speciation event defining the HOG are in-paralogs of each other [14].

Troubleshooting:

- No HOG found: The gene family might be species-specific or not conserved in the selected taxonomic scope. Try broadening the taxonomic level.

- Complex HOG structure: Multiple duplications can lead to complex HOGs. Carefully examine the HOG's taxonomic history to interpret relationships correctly.

The Orthology Conjecture represents a fundamental principle in comparative genomics, positing that orthologous genes—those related by vertical descent from a common ancestor through speciation—are more likely to conserve biological function than paralogous genes, which arise from gene duplication events [9]. This conjecture provides the foundational rationale for transferring functional annotations from characterized genes in model organisms to uncharacterized genes in newly sequenced genomes, driving discoveries across evolutionary biology, genetics, and drug development [9].

Despite its widespread application, the Orthology Conjecture has been subject to ongoing debate and empirical testing. A landmark study by Nehrt et al. challenged the conjecture, reporting that paralogs within the same species often exhibit greater functional similarity than orthologs between species at equivalent sequence divergence levels [16]. Subsequent research has contested these findings, with Altenhoff et al. demonstrating that after controlling for critical confounding factors—including authorship bias, variation in Gene Ontology term frequency, and propagated annotation bias—orthologs do indeed show weakly but significantly greater functional conservation than paralogs [17].

This Application Note provides a structured framework for assessing functional conservation between orthologous genes, offering standardized protocols and analytical resources designed for researchers investigating evolutionary relationships and functional genomics.

Quantitative Landscape of Functional Conservation

Comprehensive analysis of functional similarity between homologous genes requires careful consideration of multiple quantitative metrics derived from large-scale comparative studies. The table below summarizes key findings from major investigations testing the Orthology Conjecture.

Table 1: Comparative Functional Similarity Between Orthologs and Paralogs

| Study | Data Source | Ortholog Functional Similarity | Paralog Functional Similarity | Key Controlling Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nehrt et al. (2011) [16] | 8,900 genes from human & mouse (Experimental GO) | BP: 0.4-0.5MF: 0.6-0.7 (no correlation with sequence identity) | Higher than orthologs at high sequence identities (≥70-80%) | Protein sequence identity |

| Altenhoff et al. (2012) [17] | 395,328 pairs from 13 genomes (Experimental GO) | Significantly higher than paralogs after bias correction | Significantly lower than orthologs after bias correction | Authorship bias, GO term frequency, background similarity, propagated annotation |

| Yeast-only analysis [17] | S. cerevisiae & S. pombe experimental annotations | Normalized functional similarity higher for orthologs | Normalized functional similarity lower for paralogs | Organism-specific annotation biases |

BP = Biological Process; MF = Molecular Function; GO = Gene Ontology

Critical confounding factors identified in these studies include:

- Authorship bias: Genes annotated in the same publication show inflated functional similarity [17]

- Propagated annotation bias: Computational function transfer artificially increases similarity among closely-related sequences [17]

- Background similarity variation: Intrinsic functional similarity differs across species pairs and biological contexts [17]

Table 2: Orthology Inference Tools and Benchmarking Metrics

| Method | Approach | Strengths | Orthobench Accuracy (F-score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder [7] | Phylogenetic orthology inference with rooted gene trees | Most accurate ortholog inference; infers rooted species trees; comprehensive statistics | 3-24% higher than other methods [7] |

| PhylomeDB [7] | Tree-based database | Online resource with phylogenetic trees | Comparable to score-based methods |

| InParanoid [7] | Score-based heuristic | Fast pairwise ortholog identification | Lower than phylogenetic methods |

| OrthoMCL [18] | Graph-based clustering | Handles large datasets effectively | Lower than tree-based methods |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Phylogenetic Orthology Inference with OrthoFinder

Purpose: To identify orthologs and orthogroups across multiple species using phylogenetic methods.

Workflow:

Procedure:

Input Preparation

- Collect protein sequences in FASTA format for each species of interest

- Ensure consistent annotation and remove fragmented sequences

- For optimal results, include outgroup species to improve rooting accuracy

Software Execution

- Install OrthoFinder via conda:

conda install orthofinder -c bioconda - Run analysis:

orthofinder -f /path/to/protein/fasta/files/ - For large datasets, use

--assignoption to add species to existing analysis

- Install OrthoFinder via conda:

Result Interpretation

- Locate orthogroups in

Phylogenetic_Hierarchical_Orthogroups/N0.tsv - Find pairwise orthologs in

Orthologues/SpeciesX_vs_SpeciesY.tsv - Analyze gene duplication events in

Gene_Duplication_Events/

- Locate orthogroups in

Technical Notes: OrthoFinder's phylogenetic approach is 3-24% more accurate than heuristic methods on standard benchmarks [7]. The inclusion of outgroup species improves orthogroup inference accuracy by up to 20% [19].

Protocol 2: Controlled Functional Similarity Analysis

Purpose: To compare functional similarity between orthologs and paralogs while controlling for confounding biases.

Workflow:

Procedure:

Data Curation

- Obtain experimentally validated GO annotations (evidence codes EXP, IDA, IPI, IMP, IGI, IEP)

- Filter annotations to exclude those derived from common publications or authors

- Calculate species-specific GO term frequencies rather than using global frequencies

Similarity Measurement

- Use information-theoretic similarity measures that account for annotation specificity

- Calculate background similarity for random gene pairs within each species pair

- Normalize functional similarity scores against background similarity

Statistical Analysis

- Stratify comparisons by sequence identity bins (e.g., 50-60%, 60-70%, etc.)

- Use non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U) to compare orthologs vs. paralogs

- Perform sub-analysis focusing on specific functional categories (e.g., subcellular localization)

Technical Notes: This controlled approach revealed that orthologs show weakly but significantly higher functional similarity than paralogs, particularly for sub-cellular localization [17]. The effect is most pronounced when comparing orthologs between closely-related model organisms and human [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Orthology and Functional Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthology Inference | OrthoFinder [7], OrthoMCL [18], OMA [18] | Identify orthologs and paralogs from sequence data | Evolutionary studies, functional annotation transfer |

| Functional Annotation | Gene Ontology (GO) database [17], Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [20] | Standardized functional classification | Functional similarity quantification, pathway analysis |

| Benchmarking Resources | Orthobench [18], Quest for Orthologs [7] | Assess orthology inference accuracy | Method validation, tool selection |

| Sequence Databases | RefSeq [20], Pfam [20], eggNOG [20] | Protein families and domains reference | Gene family characterization, domain architecture analysis |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | IQ-TREE [18], MAFFT [18], TrimAL [18] | Multiple sequence alignment and tree inference | Gene tree estimation, evolutionary relationship resolution |

Concluding Remarks

The Orthology Conjecture remains a valuable guiding principle in comparative genomics, provided that analyses account for critical confounding factors and utilize robust phylogenetic methods. The protocols and resources presented here offer researchers a standardized framework for investigating functional conservation in evolutionary studies. As comparative genomics continues to expand—with recent discoveries of novel gene families from uncultivated taxa nearly tripling the known prokaryotic gene repertoire [20]—rigorous orthology assessment becomes increasingly essential for meaningful biological interpretation.

Orthology analysis forms the bedrock of comparative genomics, enabling researchers to trace the evolutionary history of genes across species. The conventional definition of orthology and paralogy is inherently genocentric, distinguishing genes related by speciation events (orthologs) from those related by duplication events (paralogs) [9]. This framework has guided functional annotation transfer for decades, operating on the principle that orthologs generally retain equivalent biological functions across different organisms [9].

However, several recent findings challenge this oversimplified perspective. Differences in domain architectures among proteins encoded by genes deemed orthologous are both common and functionally important, particularly in multicellular eukaryotes [9]. The pervasive nature of alternative splicing and alternative transcription further complicates genocentric definitions [9]. These realities necessitate a conceptual shift toward smaller, more stable evolutionary units—specifically protein domains and even sub-gene elements—to accurately describe evolutionary processes and functional relationships [9].

This Application Note details methodologies for identifying and analyzing these finer-grained evolutionary units, providing practical frameworks for researchers investigating gene evolution, function, and innovation.

Theoretical Framework: From Genes to Evolutionary Units

The Hierarchical Nature of Orthology

Orthologous relationships extend beyond simple one-to-one correspondences between genes. Complex evolutionary scenarios involving lineage-specific duplications and losses create intricate relationships best described through hierarchical orthologous groups (HOGs) [11]. HOGs represent sets of genes that descended from a single ancestral gene at each speciation node in a species tree, creating a nested structure that mirrors evolutionary history [11].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Modern Orthology Analysis

| Concept | Definition | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Orthologs | Genes related by speciation events [9] | Trace species divergence; often retain core biological functions |

| Paralogs | Genes related by duplication events [9] | Enable functional innovation through duplication and divergence |

| Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) | Sets of genes descending from a single ancestral gene at specific tree levels [11] | Capture nested evolutionary relationships across taxonomic levels |

| Root HOG | Coarse-grained gene family originating from ancestral gene at analysis root [11] | Provides framework for large-scale orthology inference |

| In-paralogs | Paralogs that duplicated after a given speciation event [9] | Indicate lineage-specific gene family expansions |

Limitations of Genocentric Orthology

The genocentric orthology model faces several critical limitations that impact evolutionary analysis and functional inference. Between-species differences in domain architectures of homologous proteins create complex networks of relationships that cannot be properly represented under genocentric definitions [9]. When proteins contain repetitive, promiscuous domains—such as ankyrin repeats or tetratricopeptide repeats—the concept of orthology at the gene level essentially breaks down [9].

These limitations have driven the recognition that stable evolutionary units often exist below the gene level. The correct description of evolutionary processes may ultimately require tracing the fates of individual nucleotides or stable protein domains, moving beyond genocentric orthology to a more nuanced framework [9].

Diagram 1: Genocentric vs. domain-centric evolutionary views (47 characters)

Methodological Approaches and Tools

Scalable Orthology Inference with FastOMA

The FastOMA algorithm addresses critical scalability challenges in orthology inference, enabling processing of thousands of eukaryotic genomes within 24 hours while maintaining high accuracy [11]. This linear scalability represents a significant advancement over traditional methods with quadratic time complexity, such as OrthoFinder and SonicParanoid [11].

FastOMA employs a two-step methodology for efficient orthology inference. First, it maps input proteomes onto reference HOGs using the alignment-free OMAmer tool, which uses k-mer-based placement for coarse-grained family assignment [11]. Subsequently, it resolves the nested structure of HOGs through leaf-to-root traversal of the species tree, identifying genes grouped together at each taxonomic level [11].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Orthology Inference Tools

| Method | Time Complexity | Reference Proteomes Processed in 24 Hours | Precision (SwissTree) | Recall (SwissTree) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastOMA | Linear [11] | 2,086 [11] | 0.955 [11] | 0.69 [11] |

| OMA | Quadratic [11] | ~50 [11] | ~0.94* | ~0.65* |

| OrthoFinder | Quadratic [11] | Not specified | High recall [11] | Highest [11] |

| SonicParanoid | Quadratic [11] | Not specified | Moderate | Moderate |

Table 3: FastOMA Algorithmic Steps and Applications

| Step | Process | Tools Used | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Family Inference | Map proteomes to reference HOGs | OMAmer [11] | Query rootHOGs |

| Unplaced Sequence Handling | Cluster unmapped sequences | Linclust [11] | Additional rootHOGs |

| Orthology Inference | Resolve nested HOG structure | Tree traversal [11] | Hierarchical Orthologous Groups |

| Downstream Analysis | Evolutionary interpretation | OMA ecosystem [11] | Phylogenetic profiles, gene histories |

Specialized Tools for Domain-Centric Analysis

AlgaeOrtho provides a specialized framework for processing ortholog inference results with a user-friendly interface [21]. Built upon SonicParanoid and the PhycoCosm database, it generates ortholog tables, similarity heatmaps, and unrooted protein trees to visualize putative orthologs across algal species [21]. This tool is particularly valuable for identifying bioengineering targets in non-model organisms, as it doesn't depend on existing protein annotations [21].

For basic ortholog identification, BLAST remains a fundamental tool. The BLASTP algorithm searches protein sequences against protein databases, with results filtered by metrics including query coverage, percent identity, and E-value (statistical measure of match significance) [22]. This approach enables ortholog discovery even in species without well-annotated genomes [22].

Diagram 2: FastOMA orthology inference workflow (42 characters)

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Domain-Centric Orthology Analysis

Objective: Identify orthologous domains and sub-gene elements across multiple species, moving beyond genocentric definitions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multi-species proteome datasets in FASTA format

- High-performance computing cluster (300+ CPU cores for large-scale analyses)

- FastOMA software suite (https://github.com/DessimozLab/FastOMA/)

- AlgaeOrtho tool for specialized taxonomic groups

- BLAST+ suite for sequence similarity searches

- Reference taxonomic tree (NCBI taxonomy or TimeTree resource)

Procedure:

Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Download proteome datasets from PhycoCosm, UniProt, or organism-specific databases

- Validate file formats and sequence integrity

- For fragmented gene models, enable FastOMA's handling of fragmented sequences [11]

FastOMA Execution and Parameter Optimization

Domain-Centric Orthology Resolution

- Extract domain architecture information from HOG members using domain databases

- Identify orthologous relationships at the domain level rather than gene level

- Analyze domain gain/loss events across the phylogenetic tree

Validation and Visualization

Troubleshooting:

- Low orthology resolution may indicate overly stringent OMAmer thresholds

- Excessive splitting of gene families may require adjustment of rootHOG merging parameters

- For non-model organisms with limited annotation, use AlgaeOrtho's annotation-independent approach [21]

Protocol: Sub-gene Element Identification

Objective: Identify and trace the evolutionary history of sub-gene elements, including specific protein domains and repetitive elements.

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein sequences with domain annotation

- Domain database (Pfam, InterPro)

- Multiple sequence alignment tools (Clustal Omega, MAFFT)

- Custom scripts for domain boundary extraction

Procedure:

Domain Annotation and Extraction

- Annotate protein sequences using domain databases

- Extract individual domain sequences based on annotated boundaries

- Create domain-specific sequence datasets for orthology analysis

Domain-Centric Orthology Inference

- Process domain sequences through standard orthology inference pipelines

- Compare domain-level orthology assignments with gene-level assignments

- Identify instances where domain orthology contradicts gene orthology

Evolutionary Analysis of Sub-gene Elements

- Reconstruct phylogenetic trees for individual domains

- Compare domain trees with species trees to identify horizontal transfer events

- Analyze evolutionary rates of domains versus full-length proteins

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Evolutionary Analysis

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastOMA | Software Algorithm | Large-scale orthology inference [11] | Genome-wide ortholog identification across thousands of species |

| OMAmer | Software Tool | k-mer-based sequence placement [11] | Ultrafast homology clustering and gene family assignment |

| AlgaeOrtho | Web Application | Ortholog visualization [21] | User-friendly ortholog identification in algal species |

| PhycoCosm | Database | Multi-omics data for algae [21] | Source of annotated proteomes for non-model organisms |

| BLAST+ Suite | Software Tools | Sequence similarity search [22] | Initial ortholog candidate identification and validation |

| TimeTree | Database | Species divergence times [11] | High-resolution species trees for improved orthology inference |

| Linclust | Software Algorithm | Sequence clustering [11] | Grouping unmapped sequences into rootHOGs |

| Tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal | Tri-O-acetyl-D-glucal, CAS:2873-29-2, MF:C12H16O7, MW:272.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Hydroxythiabendazole | 5-Hydroxythiabendazole | High-Purity Reference Standard | 5-Hydroxythiabendazole: A key metabolite for thiabendazole research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The move beyond genocentric definitions to domains and sub-gene elements represents a fundamental shift in evolutionary analysis. This approach acknowledges the complexity of gene evolution and provides a more accurate framework for understanding functional relationships across species. The protocols and tools outlined in this Application Note empower researchers to implement this refined evolutionary perspective in their orthogroup analyses.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on integrating structural protein data to improve resolution at deeper evolutionary levels, as well as incorporating gene order conservation as additional evidence for orthology assessment [11]. As sequencing initiatives continue to expand genomic datasets, these domain-centric approaches will become increasingly essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from the deluge of sequence data.

Conducting Orthogroup Analysis: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Sequence to Biological Insight

In comparative genomics, accurately identifying homology relationships between genes is fundamental to understanding evolutionary history, gene function, and phenotypic diversity. Orthologs, genes originating from speciation events, are particularly crucial for transferring functional annotations across species and reconstructing evolutionary relationships. The challenge of orthology inference has spawned two predominant computational approaches: phylogenetic tree-based methods and graph-based clustering methods. Tree-based methods like OrthoFinder leverage phylogenetic analyses to delineate evolutionary relationships, while graph-based approaches like SonicParanoid and Broccoli utilize sequence similarity networks and clustering algorithms. For researchers conducting orthogroup analysis in evolutionary studies, selecting the appropriate tool requires understanding their fundamental methodologies, performance characteristics, and suitability for specific biological questions. This Application Note provides a structured comparison of these prominent orthology inference algorithms to guide researchers in selecting optimal tools for their genomic investigations.

Algorithmic Foundations and Methodological Comparisons

Core Principles and Technical Implementations

OrthoFinder employs a comprehensive phylogenetic methodology that extends beyond basic orthogroup inference. The algorithm begins with all-versus-all sequence similarity searches but incorporates a critical innovation: a novel score transformation that eliminates gene length bias in orthogroup detection. This transformation normalizes BLAST scores based on sequence length, preventing the systematic under-clustering of short genes and over-clustering of long genes that plagued earlier methods [3]. Following this normalization, OrthoFinder infers gene trees for all orthogroups, reconstructs a rooted species tree, and maps gene duplication events to both gene and species trees [7]. This phylogenetic approach allows OrthoFinder to provide rooted gene trees, ortholog identification, and gene duplication events mapped to specific branches in the species tree. The algorithm can utilize either fast similarity search tools like DIAMOND or more accurate multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic inference methods based on user preference [7].

SonicParanoid2 represents a substantial update to the original graph-based algorithm, incorporating machine learning to enhance performance. The methodology employs two key innovations: an AdaBoost classifier that predicts and executes faster alignment directions between proteome pairs, thereby avoiding unnecessary computations, and a Doc2Vec language model that enables domain-aware orthology inference for proteins with complex domain architectures [23]. The algorithm first performs graph-based orthology inference using the optimized alignments, then conducts separate domain-based orthology inference, and finally merges the results before applying the Markov Cluster Algorithm (MCL) to infer multi-species orthogroups [23]. This hybrid approach allows SonicParanoid2 to maintain high speed while improving recall for difficult-to-detect orthologs in duplication-rich genomes.

Broccoli employs a distinct graph-based approach that reduces computational burden through k-mer clustering rather than all-versus-all alignments. The method builds similarity networks using reciprocal smallest distance pairs and applies clustering to identify homologous families. Unlike simpler graph methods, Broccoli incorporates phylogenetic information by building multiple sequence alignments and distance trees to refine orthogroup predictions [24]. This combination of fast similarity filtering with subsequent phylogenetic refinement enables Broccoli to achieve a balance between speed and accuracy, particularly for larger datasets.

Workflow Comparison and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the core methodological differences and relationships between the phylogenetic and graph-based approaches to orthology inference:

Figure 1: Workflow comparison between phylogenetic and graph-based orthology inference approaches, highlighting core methodological differences.

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Empirical evaluations across diverse datasets provide critical insights into the practical performance characteristics of orthology inference tools. The following table summarizes key benchmark results from standardized assessments:

Table 1: Performance comparison of orthology inference tools on standardized benchmark datasets

| Tool | Approach | Execution Time (QfO dataset) | Memory Footprint | Orthobench Accuracy (F-score) | Scalability (2000 MAGs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Phylogenetic | 1x (reference) | Moderate | Highest [7] | Failed to complete [23] |

| SonicParanoid2 | Graph-based + ML | 0.28x (fast mode) to 0.83x (default) | Moderate | Most accurate in recent benchmarks [23] | 1.7 days (default mode) [23] |

| Broccoli | Graph-based + phylogenetic refinement | 0.4x (fast mode) | Highest | High [24] | Failed to complete [23] |

| ProteinOrtho | Graph-based with heuristics | 0.8x (similar settings) | Lowest | Not reported | 5.7 days [23] |

Biological Context Performance

Different biological contexts present unique challenges for orthology inference. A study evaluating performance across Brassicaceae species with varying ploidy levels revealed important practical considerations:

Table 2: Algorithm performance across biological contexts with different genomic complexities

| Tool | Diploid Species Sets | Mixed Ploidy Species Sets | Notes on Biological Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | High accuracy, well-resolved groups | Maintains accuracy with complex histories | Better handling of duplication events [24] |

| SonicParanoid | High consistency with other methods | Good performance with ploidy variation | Slight discrepancies in gene content [24] [25] |

| Broccoli | Similar results to OrthoFinder/SonicParanoid | Effective with complex gene histories | Useful for initial predictions [24] |

| OrthNet | Outlier results in comparisons | Provides synteny information | Useful for colinearity analysis [24] |

Application to specific biological questions further illuminates performance differences. In identifying cold-responsive transcription factors across eudicots, orthogroup analysis successfully identified 35 high-confidence conserved cold-responsive transcription factor orthogroups (CoCoFos), including both well-characterized regulators and novel candidates [26]. This demonstrates the practical utility of these methods for discovering functionally relevant gene families across species.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Standard Orthology Inference Protocol

Materials and Input Requirements

- Protein sequence files: One FASTA file per species with amino acid sequences

- Computational resources: Multi-core processor, sufficient RAM (≥16GB recommended), storage space

- Software dependencies: Python 3.6+, BioPython, NumPy, SciPy (for OrthoFinder); additional aligners optional

Procedure

- Data Preparation

- Download or assemble proteomes for all species of interest

- Ensure consistent annotation quality across species

- Format as individual FASTA files with appropriate identifiers

Tool Installation

Basic Execution

Result Interpretation

- OrthoFinder: Analyze Orthogroups/Orthogroups.tsv and PhylogeneticHierarchicalOrthogroups/N0.tsv

- SonicParanoid2: Examine ortholog clusters in output directory

- Broccoli: Review final_orthogroups.txt and phylogenetic trees

Decision Framework for Tool Selection

The following diagram provides a structured approach for selecting the most appropriate orthology inference tool based on research objectives and dataset characteristics:

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting orthology inference tools based on research goals and practical constraints.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational resources for orthology inference studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function/Purpose | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Inference Algorithms | OrthoFinder, SonicParanoid2, Broccoli | Primary orthogroup inference | GitHub, Bioconda, GitLab |

| Sequence Search Tools | DIAMOND, MMseqs2, BLAST | Accelerated similarity searches | Standalone packages |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | MAFFT, MUSCLE, Clustal Omega | Alignment for phylogenetic methods | Package managers |

| Phylogenetic Inference | IQ-TREE, RAxML, FastTree | Gene tree reconstruction | Package managers |

| Benchmarking Resources | OrthoBench, Quest for Orthologs | Method validation and comparison | Online platforms |

| Specialized Databases | OMA, OrthoDB, EggNOG | Reference orthogroups and functional annotations | Web access, downloads |

| Visualization Tools | ITOL, FigTree, Cytoscape | Results exploration and presentation | Web-based, standalone |

Orthology inference remains a cornerstone of comparative genomics and evolutionary studies, with method selection significantly impacting downstream analyses. Based on current benchmarking results and methodological considerations:

For comprehensive evolutionary analyses requiring gene trees, duplication event mapping, and species tree inference, OrthoFinder provides the most complete phylogenetic framework, particularly for datasets where computational resources are not limiting [7].

For large-scale analyses or projects prioritizing computational efficiency, SonicParanoid2 offers an optimal balance of speed and accuracy, with machine learning enhancements that improve performance on complex gene families [23].

For standard orthogroup identification with phylogenetic refinement, Broccoli represents a viable middle ground, though scalability limitations may affect very large datasets [24].

Validation with biological benchmarks remains essential, as different methods may perform variably across specific taxonomic groups or gene families of interest [24] [18].

Future methodological developments will likely continue blending phylogenetic rigor with computational efficiency, further narrowing the performance gaps between approaches. Researchers should consider starting with rapid graph-based methods for initial exploration followed by more comprehensive phylogenetic analyses for specific gene families of interest, thereby leveraging the complementary strengths of both approaches in orthogroup analysis for evolutionary studies.

High-quality proteome data is foundational for accurate orthogroup analysis in evolutionary studies. The identification of orthologous genes—genes diverged after a speciation event—relies on precise inference from protein sequences [9]. OrthoFinder, a leading phylogenetic orthology inference method, uses protein sequences as its primary input to infer orthogroups, gene trees, and ultimately the rooted species tree [7]. The quality of input proteomes directly impacts the accuracy of distinguishing orthologues from paralogues, which is crucial for understanding gene function evolution and reconstructing species relationships [9]. This protocol outlines best practices for acquiring and pre-processing proteomic data to ensure reliable downstream orthogroup analysis.

Proteome Acquisition Strategies and Experimental Design

The method of proteome acquisition determines the type of input data available for orthogroup analysis. The choice between bottom-up and top-down approaches significantly impacts the protein sequences that will form the basis of orthology inference.

Table 1: Mass Spectrometry Acquisition Methods for Proteomics

| Method Type | Description | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Selects most abundant precursors for fragmentation | Discovery proteomics, hypothesis generation | Risk of undersampling low-abundance species; requires spectral libraries [27] |

| Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) | Fragments all precursors in predefined m/z windows | Large-scale studies, enhanced reproducibility | Enables retrospective analysis; improved with AI-driven tools like DIA-NN [27] |

| Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM)/Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) | Monitors specific predefined precursors | Targeted proteomics, absolute quantitation | High sensitivity; uses heavy isotope-labeled internal standards [27] |

For evolutionary studies where the goal is comprehensive proteome coverage for orthogroup inference, DIA methods are increasingly favored due to their comprehensive sampling of detectable peptides. Advances in hybrid MS systems such as Orbitrap Astral and timsTOF have dramatically improved sensitivity, dynamic range, and proteome coverage [27] [28]. For single-cell proteomics, which can provide insights into cellular heterogeneity in evolutionary contexts, the choice between DDA with tandem mass tags (TMT) and DIA with label-free quantification involves trade-offs between throughput and quantitative accuracy [28].

Special Considerations for Non-Model Organisms

For non-model organisms lacking well-annotated genomes, Proteomics Informed by Transcriptomics (PIT) approaches can generate sample-specific protein databases from RNA-seq data [29]. The Galaxy Integrated Omics (GIO) platform provides standardized workflows for PIT analysis, including:

- PIT protein identification without a reference genome

- PIT protein identification using a genome guide

- PIT genome annotation [29]

These approaches are particularly valuable for evolutionary studies of non-model organisms where reference proteomes are unavailable or incomplete.

Pre-processing Workflow: From Raw Data to Protein Identification

The conversion of raw MS data into reliable protein identifications requires rigorous preprocessing to manage technical variability and ensure data quality. Adherence to standardized workflows is essential for generating comparable datasets for cross-species orthogroup analysis.

Diagram 1: Proteomics Data Pre-processing Workflow for Orthogroup Analysis

Data Standardization and Peak Detection