The Bayesian Alphabet in Genomic Selection: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Bayesian alphabet models, a suite of powerful statistical methods for genomic selection.

The Bayesian Alphabet in Genomic Selection: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Bayesian alphabet models, a suite of powerful statistical methods for genomic selection. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of these models, detailing how different prior distributions address the p>>n problem common in genomic data. The guide covers core methodologies from Bayes A to BayesR, their practical implementation, and computational considerations. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, such as the influence of priors and hyperparameter tuning, and offers a rigorous validation framework by comparing Bayesian methods to other genomic prediction approaches like GBLUP and machine learning. The synthesis aims to empower scientists to select and optimize the most appropriate model for complex trait prediction in biomedical and clinical research.

Unlocking the Black Box: Core Principles of the Bayesian Alphabet

In the field of genomic selection (GS), breeders and researchers aim to predict the genetic merit of individuals using genome-wide molecular markers. A central and enduring challenge in this domain is the "p>>n" problem, where the number of molecular markers (p) vastly exceeds the number of phenotyped individuals (n) [1]. This high-dimensional data structure complicates the use of classical statistical methods, as it can lead to model overfitting and unreliable predictions.

Bayesian statistical frameworks provide a powerful solution to this problem by incorporating prior knowledge and using regularization to handle the high-dimensional marker space. A family of models, often referred to as the "Bayesian Alphabet," was developed specifically for genomic prediction and genome-wide association analyses [2]. These models allow for the simultaneous fitting of all genotyped markers to a set of phenotypes, accommodating different assumptions about the genetic architecture of traits through varying prior distributions for marker effects. This protocol outlines the application of these Bayesian models to effectively confront and overcome the p>>n problem in genomic selection.

Comparative Analysis of Bayesian Alphabet Models for p>>n

The Bayesian Alphabet encompasses a range of models, each applying different prior assumptions about the distribution of marker effects, which directly influences their performance in high-dimensional scenarios. The following table summarizes the key models, their priors, and their typical use cases.

Table 1: The Bayesian Alphabet for Genomic Prediction and GWA

| Model Name | Prior Distribution for Marker Effects | Key Feature | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayes-A [2] [3] | Normal distribution with a marker-specific variance; equivalent to a single t-distribution. | Allows for heavy-tailed distributions of effects. | Traits influenced by many markers of varying effect sizes. |

| Bayes-B [2] | A mixture prior: a point mass at zero with probability π and a scaled t-distribution with probability (1-π). | Performs variable selection; a preset proportion of markers have zero effect. | Traits with a presumed sparse genetic architecture (few QTLs). |

| Bayes-C [2] | A mixture prior: a point mass at zero with probability π and a normal distribution with probability (1-π). | Variable selection with normally distributed non-zero effects. | An alternative to Bayes-B with different shrinkage properties. |

| Bayes-Cπ [2] | Similar to Bayes-C, but the proportion π of markers with zero effects is not pre-specified but estimated from the data. | Estimates the proportion of non-zero effects from the data. | When the true genetic architecture is unknown. |

| Bayes-R [2] | A mixture of normal distributions, including one with zero variance (i.e., a null component). | Fits markers into multiple effect classes. | Precisely mapping QTLs and accounting for diverse effect sizes. |

These models are typically implemented using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which provide a flexible framework for inference and allow for the computation of posterior probabilities for hypothesis testing, thereby controlling error rates in genome-wide association analyses [2].

Protocol: A Bayesian Workflow for High-Dimensional Genomic Prediction

This protocol provides a detailed workflow for applying Bayesian Alphabet models to genomic selection data, specifically designed to address the p>>n problem.

Software and Computational Requirements

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Software Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| BGLR R Package [2] | A comprehensive software environment for running Bayesian regression models, including the entire Bayesian Alphabet. | Implements models via MCMC sampling. User-friendly. |

| JWAS [2] | (Julia for Whole-genome Analysis Software) Implements several Bayesian Alphabet methods for GWA with computational efficiency. | Known for improved computational implementation. |

| Genotypic Data | The high-dimensional predictor variables (p). Typically SNP markers from arrays or sequencing. | Format: matrix of 0, 1, 2 for diploid species. Quality control (e.g., MAF, missingness) is critical. |

| Phenotypic Data | The response variable (n). Measured trait values for the training population. | Should be adjusted for fixed effects (e.g., herd, location) prior to analysis. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A computational environment with multi-core processors and ample RAM. | MCMC sampling is computationally intensive, especially for large n and p. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Data Preparation and Quality Control. Begin by ensuring your genotypic and phenotypic datasets are properly formatted and quality-controlled. For the genotypic data, this includes filtering markers based on minor allele frequency (e.g., MAF < 0.05) and call rate (e.g., < 0.95). Phenotypic data should be checked for outliers and, if necessary, adjusted for relevant environmental factors or fixed effects. The data should be structured into a training set (with phenotypes and genotypes) and a validation or prediction set (with genotypes only).

Step 2: Model Selection and Configuration. Choose an appropriate Bayesian model from the Alphabet based on the presumed genetic architecture of your trait (see Table 1). For example, use Bayes-B for traits believed to be controlled by a few QTLs, or Bayes-A for traits with many QTLs of varying effects. Configure the model's hyperparameters. For instance, in Bayes-B, you must set the prior probability π (the proportion of markers with zero effect). For models like Bayes-Cπ, this is estimated from the data. Other hyperparameters, such as the degrees of freedom and scale for the prior distributions, also need to be specified.

Step 3: Running the Analysis via MCMC. Execute the model using MCMC sampling. A typical run should include a burn-in period (e.g., 10,000 iterations) to allow the chain to converge to the target distribution, followed by a larger number of sampling iterations (e.g., 50,000) to obtain the posterior distribution of parameters. It is crucial to save samples for all marker effects and other model parameters. For large datasets, consider running multiple chains to assess convergence.

Step 4: Model Diagnostics and Convergence Checking. After running the MCMC, assess the convergence of the chains. This can be done by visually inspecting trace plots for key parameters (e.g., genetic variance) to ensure they are stationary and well-mixed. Diagnostic statistics like the Gelman-Rubin diagnostic (when multiple chains are run) can be used to formally test for convergence.

Step 5: Estimating Genomic Breeding Values and Identifying Significant Markers. Use the posterior means of the marker effects to calculate the genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for individuals in the validation set: GEBV = Xvalβ̂, where Xval is the genotype matrix of the validation set and β̂ is the vector of posterior mean marker effects. For genome-wide association studies, identify markers with significant effects by examining the posterior inclusion probabilities (in variable selection models like Bayes-B) or the posterior distribution of individual marker effects. A common practice is to declare a marker significant if its posterior inclusion probability exceeds a threshold (e.g., 0.8) or if the 95% credible interval for its effect does not contain zero.

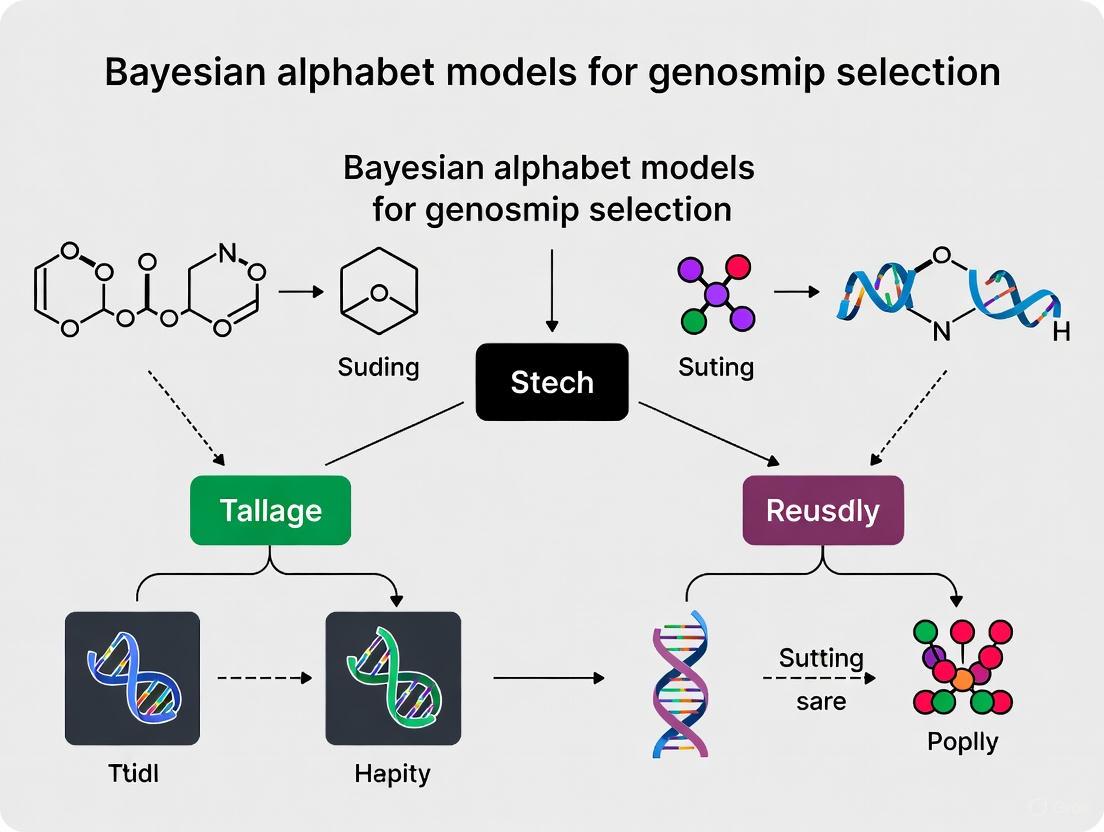

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this protocol:

Advanced Strategies: Ensemble Bayesian Models

To further improve prediction accuracy and robustness, ensemble methods that combine multiple Bayesian models have been developed. A state-of-the-art approach is the EnBayes framework, which incorporates multiple Bayesian Alphabet models (e.g., BayesA, BayesB, BayesC, etc.) into a single ensemble model [4]. In this framework, the weight assigned to each model is optimized using a genetic algorithm, creating a unified predictor that can leverage the strengths of different priors. This ensemble strategy has been shown to achieve higher prediction accuracy than individual Bayesian, GBLUP, and machine learning models, providing a powerful tool to tackle the p>>n problem [4].

Table 3: Key Steps in the EnBayes Ensemble Framework

| Step | Action | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Select Base Models | Choose a set of Bayesian Alphabet models (e.g., 8 models) to include in the ensemble. |

| 2 | Train Individual Models | Fit each base model to the training data to generate a set of preliminary GEBVs. |

| 3 | Optimize Weights | Use a genetic algorithm to find the optimal weight for each model's predictions, maximizing the ensemble's accuracy. |

| 4 | Form Final Prediction | Compute the final GEBV as the weighted sum of the predictions from all base models. |

The p>>n problem is a fundamental challenge in genomic selection. The Bayesian Alphabet models provide a statistically sound and flexible framework to address this issue by using prior distributions to regularize marker effects and prevent overfitting. The choice of model (e.g., Bayes-A, Bayes-B, Bayes-CÏ€) depends on the underlying genetic architecture of the trait. For optimal performance, especially when the true architecture is complex or unknown, ensemble methods like EnBayes, which combine the predictions of multiple Bayesian models, offer a path to higher and more robust prediction accuracy. By adhering to the protocols outlined herein, researchers can effectively implement these powerful methods to advance their genomic selection programs.

Genomic prediction has revolutionized plant and animal breeding by enabling the estimation of breeding values using genome-wide molecular markers, thereby accelerating genetic progress [5]. At the heart of this revolution lies a fundamental concept: the prior distribution. In genomic selection, statistical models built upon different prior assumptions about the distribution of marker effects across the genome are collectively known as the "Bayesian alphabet" [5]. These models reject the null hypothesis of a uniform architecture for all complex traits, instead embracing the reality that different traits exhibit distinct genetic architectures, with variations in the number of underlying quantitative trait loci (QTL) and their effect sizes [5].

The core principle of genomic prediction is to estimate the additive genetic value of an individual by summing the effects of all genome-wide markers [5]. Unlike genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that apply significance thresholds to individual markers, genomic prediction allows all markers to contribute to the prediction, with their effects estimated in a single model [5]. The choice of prior distribution for marker effects determines how this shrinkage is applied, making the selection of an appropriate Bayesian alphabet model crucial for prediction accuracy.

The Theoretical Foundation of Marker Effect Priors

From Ridge Regression to Variable Selection

The development of Bayesian alphabets represents an evolution beyond basic ridge regression approaches. Ridge regression (or rrBLUP) applies a normal prior distribution with mean zero and a specific variance to all marker effects, causing effect estimates to shrink toward zero [5]. This approach corresponds to the GBLUP method under certain conditions and works well for traits with many small-effect loci [5]. However, for traits influenced by a mix of small and large-effect loci, variable selection models that allow some marker effects to be precisely zero often provide superior performance [5].

Table 1: Core Bayesian Alphabet Models and Their Prior Distributions

| Model Name | Prior Distribution for Marker Effects | Key Assumptions about Genetic Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| BayesA | Scale mixture of normals (t-distribution) | All markers have non-zero effects; effects follow a heavy-tailed distribution |

| BayesB | Mixture with a point mass at zero and a scaled normal | Some markers have zero effect; non-zero effects follow a normal distribution |

| BayesC | Mixture with a point mass at zero and a common normal | Some markers have zero effect; non-zero effects share a common variance |

| BayesCπ | Extension of BayesC with estimable π | Proportion of non-zero markers (π) is estimated from the data |

| BayesR | Mixture of normals with different variances | Effects come from multiple normal distributions with different variances |

| Bayesian LASSO | Double exponential (Laplace) distribution | All markers have non-zero effects; stronger shrinkage of small effects toward zero |

Biological Interpretation of Priors

The mathematical formulation of each prior distribution corresponds to specific biological assumptions. For example, BayesB assumes a priori that some genomic regions have no effect on the trait, while others contain QTL of varying sizes [5]. This architecture is common for traits influenced by a few major genes alongside polygenic background. In contrast, BayesR conceptualizes that marker effects arise from multiple normal distributions with different variances, potentially corresponding to different biological categories of mutations—from small-effect regulatory variants to larger-effect coding changes [5].

The mixture of distributions in models like BayesB and BayesC introduces a sparsity principle, which is biologically plausible given that not all genomic regions are expected to influence every trait [5]. The thicker tails in the prior distributions of BayesA and Bayesian LASSO allow for better capture of large-effect loci, which is particularly valuable in diverse natural populations where large-effect alleles may still be segregating [5].

Experimental Protocols for Bayesian Alphabet Implementation

Protocol 1: Model Training and Cross-Validation

Purpose: To train Bayesian alphabet models and evaluate their prediction accuracy for genomic selection.

Materials and Reagents:

- Genotype data (e.g., SNP array or sequencing data)

- Phenotype measurements for training population

- Computing infrastructure with sufficient memory and processing power

- Genomic prediction software (e.g., BGLR, GCTA, or custom scripts)

Procedure:

- Data Quality Control: Filter genotypes based on call rate (>90%), minor allele frequency (>5%), and remove individuals with excessive missing data [6].

- Population Structure Assessment: Perform principal component analysis or relatedness analysis to understand the genetic structure of the training population.

- Phenotypic Data Correction: Adjust raw phenotypes for fixed effects (e.g., sex, farm, year-season) using mixed model approaches to obtain corrected phenotypes [6].

- Training-Test Partition: Divide the dataset into training (typically 80%) and test (20%) sets using cross-validation strategies [5].

- Model Implementation:

- For each Bayesian model, set prior parameters according to established recommendations

- Run Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling with sufficient iterations (typically 10,000-50,000)

- Discard an appropriate burn-in period (typically first 1,000-5,000 iterations)

- Model Evaluation: Calculate prediction accuracy as the correlation between genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) and observed phenotypes in the test set [5].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If MCMC convergence is poor, increase the number of iterations and burn-in period

- If computational time is excessive, consider subsetting markers or using more efficient algorithms

- If prediction accuracy is low, check for population structure and consider alternative models

Protocol 2: Multi-Breed Prediction with Differential Weighting

Purpose: To improve prediction accuracy in numerically small breeds by leveraging information from larger reference populations using multi-breed genomic relationship matrices [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- Genotype and phenotype data from multiple breeds

- Software capable of fitting multiple genomic relationship matrices (e.g., MTG2, GCTA)

- Pre-selected marker sets from GWAS meta-analysis (if available)

Procedure:

- Marker Pre-selection: Identify significant markers from a meta-genome-wide association analysis on the target trait [7].

- Dataset Preparation: Create separate genotype datasets for (a) pre-selected markers and (b) remaining markers.

- Genetic Correlation Estimation: Fit a multi-breed bivariate GREML model to estimate genetic correlation between breeds [7].

- Model Specification: Implement a multi-breed multiple genomic relationship matrices (MBMG) model that includes:

- One GRM constructed from pre-selected markers

- A second GRM constructed from the remaining markers

- Breed-specific weighting based on genetic correlations [7]

- Model Comparison: Compare prediction accuracy of the MBMG model against single-GRM models and within-breed predictions [7].

Applications: This protocol is particularly valuable for conservation genetics, wildlife disease resistance, and improving prediction in minor breeds or populations with limited reference data [7].

Advanced Implementation Strategies

Ensemble Approaches via Constraint Weight Optimization

Recent advances in Bayesian alphabet implementation have demonstrated the power of ensemble approaches. The EnBayes method incorporates multiple Bayesian models (BayesA, BayesB, BayesC, BayesBpi, BayesCpi, BayesR, BayesL, and BayesRR) within an ensemble framework, with weights optimized using genetic algorithms [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Individual vs. Ensemble Bayesian Models

| Model Type | Number of Models | Average Prediction Accuracy | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Bayesian Models | 1 | Varies by trait architecture | Specific to known genetic architectures | Risk of model misspecification |

| EnBayes Ensemble | 8 | Improved across 18 datasets [4] | Robust across diverse genetic architectures | Computationally intensive |

| Traditional GBLUP/rrBLUP | 1 | Moderate for polygenic traits | Computationally efficient | Limited for traits with major genes |

| Machine Learning Models | 1 | Variable performance | Captures non-additive effects | Prone to overfitting; "black box" |

The ensemble framework employs novel objective functions to optimize both Pearson's correlation coefficient and mean square error simultaneously [4]. Implementation requires careful consideration of the number of models included—a few more accurate models can achieve similar accuracy as including many less accurate models [4]. The bias of individual models (over- or under-prediction) also influences the ensemble's overall bias, requiring strategic model selection and weighting [4].

Integration with Single-Step Methodologies

The single-step GBLUP (ssGBLUP) approach, which integrates both genomic and pedigree data, has demonstrated consistent superiority over standard GBLUP and various Bayesian approaches for carcass and body measurement traits in commercial pigs [6]. This model can be enhanced by incorporating Bayesian principles through the use of weighted genomic relationship matrices based on marker effects estimated from Bayesian models.

Implementation Workflow:

- Estimate marker effects using Bayesian models on the genotyped population

- Calculate marker weights based on estimated effects

- Construct a weighted genomic relationship matrix

- Combine with pedigree-based relationship matrix

- Implement single-step evaluation

This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both methodologies: the ability of Bayesian models to capture diverse genetic architectures, and the power of single-step methods to incorporate all available information—including phenotypes from non-genotyped relatives [6].

Figure 1: Decision Framework for Selecting Bayesian Alphabet Models in Genomic Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Bayesian Genomic Prediction

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platforms | Illumina Bovine SNP50, GeneSeek Porcine 50K Chip | Genome-wide marker genotyping | Standardized genomic relationship matrix construction [6] [7] |

| Quality Control Tools | PLINK, GCTA | Filtering markers/individuals by call rate, MAF | Data preprocessing before model implementation [6] |

| Bayesian Analysis Software | BGLR, GCTA (Bayesian options), MTG2 | Implementation of Bayesian alphabet models | Flexible modeling with different prior distributions [5] |

| Ensemble Optimization Tools | Custom genetic algorithm implementations | Optimizing weights for ensemble models | Combining multiple Bayesian models [4] |

| Relationship Matrix Tools | blupf90, PREGSF90 | Constructing genomic relationship matrices | Single-step and multi-breed evaluations [6] [7] |

| Simulation Platforms | AlphaSimR, QMSim | Breeding program simulation | Testing model performance under different genetic architectures [8] |

| D(+)-Galactosamine hydrochloride | D(+)-Galactosamine hydrochloride, CAS:1772-03-8, MF:C6H14ClNO5, MW:215.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,5-anhydro-D-glucitol | 2,5-anhydro-D-glucitol, CAS:27826-73-9, MF:C6H12O5, MW:164.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative Performance Across Species and Traits

Empirical comparisons across species and traits provide critical insights into the performance of different Bayesian alphabet models. In commercial pig populations, studies comparing GBLUP, ssGBLUP, and five Bayesian models (BayesA, BayesB, BayesC, Bayesian LASSO, and BayesR) for carcass and body measurement traits demonstrated that model performance is trait-dependent, though ssGBLUP consistently showed strong performance [6].

For numerically small breeds, multi-breed models that differentially weight pre-selected markers have shown significant advantages. Research on Jersey and Holstein cattle demonstrated that a multi-breed multiple genomic relationship matrices (MBMG) model improved prediction accuracy by 23% on average compared to single-GRM models [7]. This approach uses pre-selected markers from meta-GWAS analyses in separate relationship matrices, effectively leveraging information from larger breeds to improve predictions in smaller populations [7].

The genetic correlation between breeds significantly influences the success of across-breed prediction. Simulation studies show that as the genetic correlation between breeds decreases (from 1.0 to 0.25), prediction accuracy declines, but the relative advantage of sophisticated multi-breed models increases [7].

Figure 2: Multi-Breed Genomic Prediction Workflow with Differential Marker Weighting

Future Directions and Implementation Considerations

The future of Bayesian alphabets in genomic selection lies in several promising directions. Ensemble methods that strategically combine multiple Bayesian models show consistent improvements in prediction accuracy across diverse crop species [4]. The integration of machine learning approaches with traditional Bayesian methods offers potential for capturing non-linear relationships and epistatic interactions [8] [9]. As identified in recent research, non-parametric models like neural networks show potential for maintaining genetic variance while achieving competitive gains, though their performance can be less stable than traditional parametric models [8].

For practical implementation, key considerations include:

- Training population design: Diverse training sets that match the testing population in genetic makeup improve prediction accuracy [8]

- Marker density: Increasing marker density improves accuracy in low-density panels, but plateaus in medium-to-high-density scenarios [6]

- Computational efficiency: While ensemble Bayesian approaches offer improved accuracy, they require substantial computational resources [4]

- Model updating frequency: Regular model retraining with recent data maintains prediction accuracy over time [8]

The democratization of genomic selection through user-friendly software and data management tools continues to expand the application of Bayesian alphabet models across diverse breeding programs [9]. As these methods become more accessible, their power to shape predictions through informed priors will play an increasingly important role in accelerating genetic gain for agriculture, conservation, and biomedical applications.

Genomic Selection (GS) has revolutionized animal and plant breeding by enabling the prediction of genetic merit using dense genetic markers across the entire genome [2]. The foundational work of Meuwissen, Hayes, and Goddard in 1 introduced a suite of Bayesian hierarchical models for this purpose, which subsequently became known as the "Bayesian Alphabet" [2] [10]. These methods address the critical statistical challenge of estimating the effects of tens or hundreds of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) when the number of genotyped and phenotyped training individuals is often much smaller [11] [2].

The Bayesian Alphabet models primarily differ in their prior distributions for SNP effects, which embody differing assumptions about the genetic architecture of quantitative traits—that is, the number and effect sizes of underlying quantitative trait loci (QTL) [2] [10]. These models offer a flexible framework not only for genomic prediction but also for genome-wide association (GWA) studies, as they fit all genotyped markers simultaneously, thereby accounting for population structure and mitigating multiple-testing problems [2]. This application note provides a detailed overview of the core Bayesian Alphabet models, their extensions, and practical protocols for their implementation in genomic selection research.

Core Models of the Bayesian Alphabet

Foundational Methods: BayesA and BayesB

The first two letters of the alphabet, BayesA and BayesB, set the stage for all subsequent developments.

- BayesA assumes that all SNPs have a non-zero effect on the trait. The prior for each SNP effect is a univariate Student's t-distribution, which has heavier tails than a normal distribution. This formulation allows for more robust shrinkage of effect sizes, meaning SNPs with small effects are shrunk substantially toward zero, while those with larger effects are shrunk less [11] [12] [10].

- BayesB introduces a key refinement: variable selection. It assumes that only a fraction (

1 - π) of SNPs have a non-zero effect, while the remaining proportion (π) have exactly zero effect. The non-zero effects are also assumed to come from a Student's t-distribution [11] [2] [10]. This model is particularly suited for traits influenced by a few QTL with relatively large effects.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Bayesian Alphabet Models

| Model | Prior on SNP Effects | Key Assumption | Variance Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| BayesA | Scaled-t distribution [12] [10] | All SNPs have some effect [10]. | Each SNP has its own variance [11] [10]. |

| BayesB | Mixture of a point mass at zero and a scaled-t distribution [2] [12] | Only a fraction (1 - π) of SNPs have non-zero effects [10]. |

Each non-zero SNP has its own variance [11] [10]. |

| BayesC | Mixture of a point mass at zero and a normal distribution [2] [12] | Only a fraction (1 - π) of SNPs have non-zero effects [10]. |

All non-zero SNPs share a common variance [11] [2]. |

A significant drawback of the original BayesA and BayesB implementations is that key hyperparameters—the proportion of zero-effect SNPs (π) and the scale parameter of the prior for SNP variances (S²)—were treated as known and fixed by the user [11] [13]. This specification can strongly influence the shrinkage of SNP effects and may not reflect the true genetic architecture learned from the data [11].

Evolutionary Extensions: BayesCÏ€, BayesDÏ€, and BayesR

To address the limitations of the original models, several extended methods were developed.

- BayesCÏ€: This model is similar to BayesC but treats the prior probability

πthat a SNP has a zero effect as an unknown parameter with a uniform(0,1) prior, which is estimated from the data [11] [2]. This allows the model to learn the true sparsity of SNP effects. Furthermore, all non-zero SNP effects share a common variance [11]. Estimates ofπfrom BayesCπ have been shown to be sensitive to the number of underlying QTL and training data size, providing valuable insights into genetic architecture [11] [14]. - BayesDπ: This extension of BayesB also treats

πas an unknown. Additionally, it addresses another drawback of BayesA/B by treating the scale parameter (S²) of the inverse chi-square prior for the locus-specific variances as an unknown with its own (Gamma) prior, thereby improving Bayesian learning [11]. - BayesR: This model uses a finite mixture of normal distributions as the prior for SNP effects. Typically, the mixture includes a component with zero effect (a point mass at zero), one or more components with small-to-moderate variances, and a component with a larger variance [2] [13]. This flexible prior allows for more nuanced modeling of the genetic architecture by simultaneously performing variable selection and assigning SNPs to different effect-size categories [2].

Diagram 1: Logical relationships and evolution of key Bayesian Alphabet models.

Performance Analysis and Comparison

Accuracy and Inference Across Models

The choice of Bayesian model significantly impacts the accuracy of Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs) and the inference of genetic architecture.

- Accuracy of GEBVs: For many traits, the prediction accuracies of alternative Bayesian methods are often similar [11] [10]. However, patterns emerge based on genetic architecture:

- Bayesian methods (e.g., BayesB, BayesCÏ€) generally outperform BLUP-based methods for traits governed by a few genes or QTLs with relatively larger effects [10].

- BLUP methods (e.g., GBLUP) can show higher accuracy for traits controlled by many small-effect QTLs, as they assume all markers contribute equally [10].

- Studies on dairy cattle data have shown that for some traits, simpler models like BayesA can be a good choice for GEBV prediction, while BayesCÏ€ offers a good balance of computing effort and accuracy for routine applications [11].

- Inference of Genetic Architecture: A key advantage of models like BayesCÏ€ and BayesBÏ€ is their ability to infer the proportion of non-zero effect SNPs (

π). Estimates ofπare sensitive to the number of simulated QTL and training data size, providing direct insight into genetic architecture [11]. For instance, in Holstein cattle,πestimates suggested that milk and fat yields are influenced by QTL with larger effects compared to protein yield and somatic cell score [11].

Table 2: Performance and Computational Characteristics of Bayesian Models

| Model | Typical Use Case / Genetic Architecture | Inference on Genetic Architecture | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| BayesA | Traits with many small-to-moderate effect QTLs [10]. | Limited; fixed hyperparameters. | Can be high (implementation dependent) [11]. |

| BayesB | Traits with a few large-effect QTLs (sparse architecture) [10]. | Limited; fixed π. | Moderate [11]. |

| BayesCπ | General use; infers sparsity of effects [11]. | Estimates π, informing on QTL number [11] [14]. | Shorter than BayesDπ [11]. |

| BayesR | Complex architectures with a mix of effect sizes [2]. | Infers proportion of SNPs in different effect-size classes [2]. | Moderate to high. |

Advanced Modifications and Applications

The Bayesian Alphabet framework continues to evolve with modifications that enhance its power and applicability.

- Spatial Correlation (Antedependence Models): Conventional models assume SNP effects are independent. Ante-BayesA and Ante-BayesB incorporate spatial correlation between SNP effects based on their physical proximity on the chromosome, modeling a first-order antedependence structure [15]. This can increase prediction accuracy, especially when linkage disequilibrium (LD) between markers is high, with improvements of up to 3.6% reported [15].

- Locus-Specific Priors (BayesBÏ€): An improved version of BayesB, BayesBÏ€, uses locus-specific

πvalues instead of a single globalπ[13]. These priors can be informed by previous GWAS p-values, integrating prior knowledge of genetic architecture. This approach has been shown to improve genomic prediction accuracy by up to 7.6% for traits controlled by large-effect genes [13]. - Application in Genome-Wide Association (GWA): By fitting all markers simultaneously, Bayesian GWA methods implicitly control for population structure. They can more precisely map QTLs compared to standard single-marker GWAS because the signal from a causal locus can be jointly captured by a group of SNPs in LD with it [2]. Power can be further enhanced by using informative priors based on functional annotation or previous studies [2].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Implementing Bayesian Alphabet Models

This protocol outlines the key steps for applying Bayesian models using dedicated software like the BGLR package in R [2] [12].

Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Genotypic Data: Assemble a matrix of SNP genotypes for all individuals, typically coded as 0, 1, or 2 copies of a reference allele. Perform quality control: filter SNPs based on minor allele frequency (e.g., MAF < 0.05) and call rate [16] [10].

- Phenotypic Data: Process and adjust phenotypic records for relevant fixed effects (e.g., herd, year, season, laboratory batch) to create a vector of corrected phenotypes. For multi-trait analysis, prepare a matrix of correlated phenotypes.

- Population Structure: Conduct a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the genotype matrix to visualize and understand population stratification, which can influence model performance [17].

Model Training and Cross-Validation

- Training/Test Set Partitioning: Split the data into training and validation sets. Use methods like k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) with multiple replications to obtain robust estimates of prediction accuracy [10]. For optimal resource allocation, employ targeted training population optimization (T-Opt), which uses information from the test set to select a training set that maximizes prediction accuracy, especially when the training population size is small [17].

- Model Configuration:

- Select the appropriate Bayesian model (e.g., BayesA, B, CÏ€) based on assumptions about the trait's genetic architecture.

- Specify the number of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations (e.g.,

nIter = 6000) and burn-in steps (e.g.,burnIn = 1000) [12]. - Use default priors for hyperparameters or set them based on prior knowledge.

MCMC Execution and Diagnostics

- Run the MCMC sampler for the selected model.

- Monitor convergence by inspecting trace plots of key parameters (e.g., residual variance, genetic variance) and using diagnostic statistics (e.g., Gelman-Rubin statistic) to ensure the chain has stabilized.

Post-Processing and Analysis

- GEBV Calculation: For the validation set, calculate GEBVs as the sum of the estimated SNP effects for each individual.

- Accuracy Assessment: Compute the Pearson correlation coefficient between the predicted GEBVs and the observed (corrected) phenotypes in the validation set [16] [10].

- Model Comparison: Compare the predictive accuracy and bias of different models to select the best one for the trait and population under study.

Diagram 2: Standard workflow for genomic prediction using Bayesian Alphabet models.

Protocol for Multi-trait and Enhanced GWA Analysis

Multi-trait Genomic Prediction:

- Objective: Leverage genetic correlations between traits to improve prediction accuracy for difficult-to-measure or low-heritability traits.

- Procedure: Use multi-trait versions of Bayesian models (e.g., multi-trait BayesA, BayesB) [2]. Input is a matrix of phenotypes for multiple correlated traits. The model estimates a covariance matrix for SNP effects across traits, allowing information from one trait to inform predictions of another [16].

Enhanced Genome-Wide Association Analysis:

- Objective: Identify genomic regions associated with traits while controlling for population structure and all other marker effects.

- Procedure:

- Run a Bayesian variable selection model (e.g., BayesB, BayesCÏ€) on the full dataset.

- Instead of examining single SNPs, analyze the posterior inclusion probabilities (PIP) for each SNP or the estimated effects of windows of adjacent SNPs [2].

- A high PIP for a SNP indicates strong evidence that it has a non-zero effect. Windows of SNPs with consistently high effects or PIPs pinpoint genomic regions likely to contain QTLs [2] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Bayesian Genomic Selection

| Category / Item | Specification / Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platform | High-density SNP arrays or sequencing (GBS, WGS) to generate genome-wide marker data. | Provides the matrix of genotypes (Z) for the prediction model [11] [16]. |

| Phenotyping Systems | High-throughput phenotyping tools (e.g., Tomato Analyzer for plants, digital sensors for animals) [18]. | Generates accurate, quantitative phenotypic data (y) for training models [16] [18]. |

| Statistical Software | `BGLR` R package [12] [10], `Gensel` [2], `JWAS` [2]. | Provides efficient, well-tested implementations of Bayesian Alphabet models for applied research. |

| Computing Infrastructure | High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or server with adequate memory and multi-core processors. | Enables practical MCMC sampling for large datasets (n > 10,000, p > 50,000), which is computationally intensive [11]. |

| 4-Fluoro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole | 4-Fluoro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole, CAS:29270-55-1, MF:C6H3FN2O, MW:138.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| O-Acetyl-L-homoserine hydrochloride | O-Acetyl-L-homoserine hydrochloride, MF:C6H12ClNO4, MW:197.62 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In genomic selection, a core challenge is identifying a subset of genetic markers, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), that have a true biological association with a complex trait from among thousands or millions of candidates. Bayesian variable selection methods provide a powerful statistical framework for this task by incorporating sparsity-inducing prior distributions that effectively separate meaningful genetic signals from noise. The "Bayesian alphabet" of models, including BayesA, BayesB, and their extensions, primarily differs in how these prior distributions are specified, leading to distinct shrinkage behaviors and selection properties. Among these, spike-and-slab priors represent a fundamentally different approach from continuous shrinkage priors, offering unique advantages for genomic prediction and association studies where the true genetic architecture is often characterized by a mixture of markers with null, small, and large effects [19] [20].

Spike-and-slab formulations explicitly model the binary inclusion status of each predictor, creating a two-group model that naturally aligns with the biological assumption that only a fraction of genotyped markers influence complex traits. This methodological distinction has profound implications for variable selection accuracy, computational efficiency, and practical implementation in genomic research. This article examines the key differentiators between spike-and-slab priors and alternative shrinkage methods, provides structured comparisons of their performance characteristics, and offers detailed protocols for their application in genomic studies.

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanism of Action

Hierarchical Structure of Spike-and-Slab Priors

The spike-and-slab prior operates through a discrete mixture distribution that explicitly models the probability that a given variable should be included in the model. The fundamental hierarchical structure consists of a binary inclusion indicator (γj) for each genetic marker j, which follows a Bernoulli distribution with inclusion probability π. The prior distribution for the marker effect (βj) is then specified conditionally on this indicator:

- Spike component: When γj = 0, βj follows a distribution highly concentrated around zero (typically a point mass at zero or a normal distribution with very small variance)

- Slab component: When γj = 1, βj follows a distribution with heavier tails that allows effects to escape shrinkage (such as a normal or t-distribution) [21] [20]

This formulation creates a bimodal posterior distribution that naturally separates markers into "included" and "excluded" categories, performing simultaneous variable selection and effect size estimation. The mechanism directly controls the sparsity of the model through the inclusion probability π, which can itself be estimated from the data, allowing the model to self-adapt to the underlying genetic architecture of the trait [22] [21].

Comparative Shrinkage Mechanisms in Bayesian Alphabet

Alternative approaches in the Bayesian alphabet employ continuous shrinkage priors that do not explicitly include binary inclusion indicators. These methods achieve variable selection through differential shrinkage of marker effects based on their perceived importance:

- BayesA uses a t-distribution prior, applying heavier shrinkage to small effects while allowing larger effects to persist

- BayesB employs a mixture distribution with a point mass at zero and a scaled t-distribution, sharing conceptual similarities with spike-and-slab but differing in implementation

- BayesC and BayesCÏ€ use a mixture of a point mass at zero and a normal distribution, with BayesCÏ€ estimating the mixture proportion from the data

- Global-local priors (e.g., Horseshoe, Horseshoe+) use a hierarchy of scale parameters with a global shrinkage parameter (τ) that pulls all effects toward zero and local parameters (λ_k) that allow individual markers to escape shrinkage [20]

The key philosophical difference lies in how these methods conceptualize sparsity: spike-and-slab frameworks explicitly model the discrete inclusion process, while shrinkage methods rely on continuous selective contraction of coefficients [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Prior Structures in Bayesian Variable Selection Methods

| Method | Prior Structure | Sparsity Mechanism | Key Hyperparameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spike-and-Slab | Discrete mixture with binary inclusion indicators | Explicit variable selection | Inclusion probability (Ï€), slab variance |

| BayesA | Student's t-distribution | Continuous shrinkage | Degrees of freedom, scale parameter |

| BayesB | Mixture with point mass at zero and t-distribution | Semi-explicit selection | Inclusion probability, degrees of freedom |

| Horseshoe | Global-local normal scale mixture | Continuous shrinkage with heavy tails | Global shrinkage (τ), local shrinkage (λ_k) |

| BayesCÏ€ | Mixture with point mass at zero and normal | Semi-explicit selection | Data-driven inclusion probability (Ï€) |

Performance Characteristics and Quantitative Comparisons

Statistical Properties in Genomic Applications

Spike-and-slab priors exhibit distinct statistical properties that impact their performance in genomic prediction and variable selection:

- Selective shrinkage: Effects identified as belonging to the slab component experience minimal shrinkage, while effects in the spike component are strongly shrunk toward zero. This creates a bimodal behavior that can better accommodate traits with major genes amid a polygenic background [22]

- Self-adaptivity: By estimating the inclusion probability π from the data, spike-and-slab methods automatically adjust to the sparsity level of the underlying trait architecture without requiring prespecified tuning parameters [22]

- Uncertainty quantification: Unlike many shrinkage methods, spike-and-slab provides direct posterior probabilities of inclusion (PPI) for each marker, offering intuitively interpretable measures of confidence in selection decisions [23]

- False discovery control: When combined with modern enhancements like knockoff filters, spike-and-slab frameworks can provide rigorous false discovery rate control while maintaining power to detect true associations [24]

In comparative studies, these properties have translated to practical advantages in specific genomic scenarios. For instance, the spike-and-slab quantile LASSO (ssQLASSO) has demonstrated robustness to outliers and heavy-tailed distributions in cancer genomics applications, maintaining performance where conventional methods faltered [22]. Similarly, in high-dimensional transcriptomic analyses, rank-based Bayesian variable selection with spike-and-slab priors showed superior robustness to data generating processes and improved feature selection accuracy compared to alternative approaches [23].

Computational Considerations and Scalability

The implementation of spike-and-slab methods involves unique computational challenges and opportunities:

- EM algorithms: For many spike-and-slab formulations, efficient Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithms can be derived that provide fast maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation. These approaches cycle through markers one at a time, updating posterior inclusion probabilities and effect sizes in a coordinate descent framework [22] [21]

- MCMC sampling: Traditional Bayesian inference for spike-and-slab models employs Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, which can be computationally intensive for genome-scale data but provide full posterior distributions [19] [20]

- Variational inference: Recent advances have developed variational inference approaches for spike-and-slab models, approximating the posterior distribution with a tractable alternative to reduce computational burden while maintaining accuracy [21]

The computational advantage of certain spike-and-slab implementations is particularly notable in robust regression settings. For the ssQLASSO method, the adoption of an asymmetric Laplace distribution for the likelihood unexpectedly enabled efficient computation via soft-thresholding rules within EM steps, a phenomenon rarely observed for robust regularization with non-differentiable loss functions [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Genomic Prediction Methods

| Method | Variable Selection Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Robustness to Outliers | Handling of Polygenic Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spike-and-Slab | High (explicit selection) | Moderate to high (depends on implementation) | Moderate (enhanced in robust variants) | Good with self-adapting inclusion |

| BayesA | Low (continuous shrinkage) | High | Low | Excellent |

| BayesB | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Good |

| BayesCÏ€ | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Good with estimated sparsity |

| Horseshoe | High (pseudo-selection) | Moderate | Low to moderate | Good |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol: Implementation of Spike-and-Slab Quantile Regression for Genomic Data

This protocol outlines the implementation of the spike-and-slab quantile LASSO (ssQLASSO) for robust variable selection in genomic applications, particularly suited for traits with non-normal error distributions or outlier contamination [22].

Materials and Reagents

- Genotypic data (SNP matrix, n×p, where n is sample size and p is number of markers)

- Phenotypic measurements for the trait of interest

- Computing environment with R installed

- R package

emBayes(available from CRAN)

Procedure

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Standardize both genotype matrix and phenotype vector to mean zero and unit variance

- Check for missing data and implement appropriate imputation if needed

- For quantile regression, specify the desired quantile level Ï„ (typically 0.25, 0.5, or 0.75)

Model Specification

- Define the hierarchical model structure:

- Likelihood: Asymmetric Laplace Distribution (ALD) with skewness parameter Ï„

- Prior for marker effects: Spike-and-slab mixture with

β_j ∼ γ_j × N(0, σ²/τ) + (1-γ_j) × δ_0whereδ_0is point mass at zero - Prior for inclusion indicators:

γ_j ∼ Bernoulli(π) - Hyperprior for inclusion probability:

π ∼ Beta(a,b)

- Define the hierarchical model structure:

Parameter Initialization

- Initialize effect sizes

β_jto small random values or estimates from marginal regression - Set initial inclusion probabilities

γ_jto 0.5 for all markers - Set hyperparameters a and b to reflect prior belief about sparsity (e.g., a=1, b=1 for uniform prior)

- Initialize effect sizes

EM Algorithm Implementation

- E-step: For each marker j, compute the posterior inclusion probability (PIP):

γ_j^* = P(γ_j=1|β, y, X) = [π × N(β_j; 0, σ²/τ)] / [π × N(β_j; 0, σ²/τ) + (1-π) × δ_0(β_j)]

- M-step: Update parameters:

- Update

βusing coordinate descent with soft-thresholding rules - Update

πas the mean of the posterior inclusion probabilities:π^* = (sum(γ_j^*) + a - 1) / (p + a + b - 2)

- Update

- Iterate until convergence of evidence lower bound (ELBO)

- E-step: For each marker j, compute the posterior inclusion probability (PIP):

Post-processing and Interpretation

- Select markers with posterior inclusion probability > 0.5 (or a more stringent threshold)

- Calculate predicted genetic values as

ŷ = Xβ^* - Evaluate prediction accuracy in independent validation set

Protocol: Bayesian Variable Selection with Spatial Information

This protocol extends the basic spike-and-slab framework to incorporate spatial information in genome-wide association studies, modeling the clustering of significant markers in genomic regions [24].

Materials and Reagents

- Genotype data with chromosomal positions

- Phenotype measurements

- Population structure covariates (if available)

- Computing environment with R/Python and specialized Bayesian software (e.g., R packages

BGLRor custom MCMC code)

Procedure

Data Preparation

- Annotate markers with genomic coordinates

- Calculate linkage disequilibrium (LD) matrix or neighborhood structure

- Generate principal components to account for population stratification

Spatial Prior Specification

- Define Markov Random Field (MRF) prior for inclusion indicators:

P(γ|Ω) ∠exp(α∑γ_j + Ï∑_{j∼k} Ω_{jk} I(γ_j=γ_k))- where

j∼kindicates neighboring markers,Ω_{jk}measures connectivity

- Set up neighborhood structure based on genomic proximity or LD patterns

- Define Markov Random Field (MRF) prior for inclusion indicators:

Model Implementation via MCMC

- Initialize all parameters

- For each MCMC iteration:

- Sample inclusion indicators γ using spatial-aware conditional probabilities

- Sample effect sizes β from conditional normal distributions

- Update spatial smoothing parameter Ï

- Update other hyperparameters

- Run sufficient iterations for convergence (typically 10,000-50,000 after burn-in)

False Discovery Control with Knockoffs

- Generate knockoff genotypes that preserve covariance structure but break association with phenotype

- Include both original and knockoff markers in the model

- Compute posterior inclusion probabilities for both sets

- Control false discovery rate by comparing probabilities between original and knockoff features

Result Interpretation

- Identify genomic regions with clustered inclusions

- Annotate significant regions with gene information

- Calculate posterior probabilities for pathway enrichment

Table 3: Essential Resources for Bayesian Variable Selection Experiments

| Resource | Specification | Application Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypic Data | SNP array or sequencing data; minimum 40K markers for livestock, >500K for human | Primary predictor variables | Standardization crucial; quality control essential; imputation may be needed |

| Phenotypic Data | Trait measurements; continuous or binary; n > 1000 preferred | Response variable | Power depends on heritability and sample size; pre-correction for fixed effects may be needed |

| BGLR R Package | Multi-trait Bayesian regression software | Implementation of various Bayesian alphabet models | Supports multiple prior structures; efficient Gibbs sampling; well-documented |

| emBayes R Package | EM-based Bayesian implementation | Fast approximation for spike-and-slab models | Computational efficiency; suitable for large datasets |

| High-Performance Computing | Multi-core processors; sufficient RAM for large matrices | Handling genomic-scale data | Parallel processing reduces computation time; memory requirements scale with n×p |

| Reference Genome | Species-specific annotation (e.g., EquCab3.0 for horse) | Interpretation of selected markers | Functional annotation of significant regions; pathway analysis |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The development of spike-and-slab methodologies continues to evolve with several promising research directions:

- Integration with deep learning: Bayesian neural networks with spike-and-slab variable selection (NetSparse) have shown promise for capturing non-additive genetic effects while maintaining sparsity in genomic prediction [25]

- Multi-trait frameworks: Extensions of spike-and-slab priors to multivariate response models enable the joint analysis of correlated traits, potentially increasing power to detect pleiotropic effects [26]

- Spatial-temporal applications: Incorporating spatial genomic information through Markov random fields or functional data analysis approaches improves detection of clustered causal variants [24]

- Robust likelihood formulations: Combining spike-and-slab priors with heavy-tailed error distributions or quantile regression frameworks enhances resilience to data irregularities common in genomic studies [22]

These advanced applications demonstrate the continuing relevance of spike-and-slab methodologies in an era of increasingly complex genomic data structures, maintaining their foundational principle of explicit variable selection while adapting to contemporary analytical challenges.

The dissection of the genetic architecture underlying complex traits—encompassing the number and locations of quantitative trait loci (QTLs), their effects, and interactions—is a fundamental challenge in genetics. The "Bayesian alphabet," a suite of hierarchical regression models, has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, enabling researchers to move beyond the limitations of single-marker analyses and assumptions of simple additive architectures [27]. These models are particularly suited for the high-dimensionality of genomic data, where the number of markers (p) far exceeds the number of phenotypic observations (n). In this p > n scenario, parameters are not fully identified by the likelihood alone, and the prior distributions specified in Bayesian models play an influential, unavoidable role in shaping inferences about genetic architecture [27]. While this means claims about genetic architecture from these methods must be made cautiously, Bayesian models provide a flexible framework for simultaneously mapping genome-wide interacting QTLs and predicting complex traits [28] [27].

At their core, these methods perform whole-genome regression, modeling phenotypes based on dense markers across the genome. The general statistical model can be expressed as:

y = Xβ + Wa + e

Here, y is the vector of phenotypes, X is a design matrix for fixed effects, β is the vector of fixed effect coefficients, W is a matrix of marker genotypes (e.g., coded as 0, 1, 2), a is the vector of random marker effects, and e is the vector of residual errors [27] [11]. The distinguishing feature of each letter in the Bayesian alphabet lies in the prior distributions assigned to the marker effects (a), which control how shrinkage is applied to effect sizes and thereby influence the inferred genetic architecture [27] [29].

The Bayesian Alphabet: Model Priors and Genetic Architecture

Different Bayesian models make distinct assumptions about the distribution of genetic effects, which in turn shapes how they reveal QTLs. The following table summarizes the key members of the Bayesian alphabet and their interpretation for genetic architecture.

Table 1: Key Members of the Bayesian Alphabet for QTL Mapping

| Model | Prior Distribution for Marker Effects | Implied Genetic Architecture | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| BayesA | All markers have non-zero effects; each follows a t-distribution (locus-specific variances). | Many QTLs of varying effect sizes, all with non-zero contributions. A polygenic background with some loci having larger effects. | [29] [11] |

| BayesB | A proportion (Ï€) of markers have zero effect; the rest have locus-specific variances. |

A sparse architecture: a limited number of QTLs with larger effects, against a background of many markers with no effect. | [28] [11] |

| BayesCÏ€ | A proportion (Ï€) of markers have zero effect; the rest share a common variance. |

Similar to BayesB, but infers the proportion of non-zero effects (Ï€) from the data, informing on the number of causal variants. |

[11] |

| BayesR | Effects come from a mixture of normal distributions, including one with zero variance. | Capable of differentiating markers with large, moderate, small, or zero effects, providing a nuanced view of architecture. | [30] [31] |

| Bayesian Lasso (BL) | Effects follow a double-exponential (Laplace) distribution, inducing stronger shrinkage on small effects. | A spectrum of many small-effect QTLs, with a fewer number of medium- to large-effect QTLs standing out. | [29] |

The parameter π in models like BayesB and BayesCπ is particularly informative. It represents the prior probability that a marker has no effect on the trait. When treated as an unknown parameter estimated from the data, as in BayesCπ, its posterior estimate can provide insight into the underlying genetic architecture—for instance, suggesting whether a trait is influenced by a few or many QTLs [11]. Studies applying these models have found that traits like milk yield and fat yield in cattle appear to be influenced by QTLs with larger effects, whereas protein yield and somatic cell score are governed by QTLs with smaller effects [11].

Application Notes and Protocols

This section provides a detailed workflow for applying Bayesian models to infer the genetic architecture of a quantitative trait, using a real dataset from a Holstein cattle population as a benchmark example [30] [31].

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Bayesian QTL Mapping

Objective: To detect the number, location, and effects of QTLs for a quantitative trait using a Bayesian alphabet model.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Specification / Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic Data | Vector of phenotypic values (e.g., Estimated Breeding Values, de-regressed proofs). Correct for fixed effects (e.g., herd, season, sex). | Data quality is paramount. Ensure phenotypes are normally distributed or transformed; consider robust models for non-normal traits [28]. |

| Genotypic Data | High-density SNP genotypes (e.g., 122,672 SNPs in cattle [30]). Quality control: apply filters for MAF (>0.05), call rate (>0.90), and HWE. | Imputation to a common marker set may be necessary. Centering and scaling genotypes is standard practice. |

| Software Platform | Specialized software for Bayesian MCMC sampling (e.g., bayz [32], GS suite, BLR, JWAS). | Computing time is a significant factor. GBLUP is fastest, while Bayesian methods can require >6x more computational time [30]. |

| Prior Distributions | Choice of model (e.g., BayesCπ) and hyperparameters (e.g., ν_a, S_a² for scale). |

The prior is influential in p > n settings. Sensitivity analysis of hyperparameters is recommended [27] [11]. |

| MCMC Sampler | A computing cluster/server (e.g., HP server with 20 threads [30]). Configure for long run-times. | Required for sampling from the joint posterior distribution of all unknown parameters. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Prepare the phenotype (

y) and genotype (W) matrices. Partition the data into training and validation sets using a method like fivefold cross-validation with 5 repetitions [30]. - Model Specification: Select an appropriate Bayesian model. For a balanced approach that infers the number of QTLs, BayesCÏ€ is a strong starting point [11]. The statistical model is:

y = 1μ + Wa + ewhereais the vector of SNP effects with prior as defined in Table 1 for BayesCπ. - Prior Elicitation: Set priors for parameters. For BayesCπ, typical settings include:

μ: Flat prior.a_k | π, σ_a²: Mixture prior:0with probabilityπ, andN(0, σ_a²)with probability(1-π).π:Uniform(0, 1).σ_a²:Scaled Inverse Chi-square(ν_a, S_a²), whereν_ais degrees of freedom (e.g., 4.2) andS_a²is a scale parameter derived from the additive genetic variance [11].σ_e²:Scaled Inverse Chi-square(ν_e, S_e²).

- MCMC Execution: Run the MCMC sampler (e.g., Gibbs sampling with Metropolis-Hastings steps) for a sufficient number of iterations (e.g., 50,000 to 100,000), discarding the first 20% as burn-in.

- Posterior Analysis:

- QTL Detection: Identify genomic regions where the posterior inclusion probability (PIP) for a marker or window of markers is high (e.g., >0.8) [32]. The estimated

Ï€directly informs the sparsity of QTLs. - Effect Estimation: Plot the posterior means of

aagainst genomic position to visualize effect sizes and localize major QTLs.

- QTL Detection: Identify genomic regions where the posterior inclusion probability (PIP) for a marker or window of markers is high (e.g., >0.8) [32]. The estimated

- Model Evaluation: Calculate the prediction accuracy in the validation set as the correlation between observed phenotypes and genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs). Compare models based on accuracy and unbiasedness.

Figure 1: A standard workflow for QTL mapping using Bayesian models, from data preparation to the interpretation of genetic architecture.

Protocol 2: Advanced Integrative Analysis with Transcriptome Data

Objective: To partition genetic variance and distinguish between regulatory and structural QTLs by jointly modeling genome-wide SNPs and transcriptome data [32].

Background: This integrative approach helps bridge the genotype-phenotype gap. Expression QTLs (eQTLs) are identified as SNPs whose effects on the trait are mediated through transcript abundance—their effects diminish when gene expression is added to the model [32].

Procedure:

- Data Integration: Collect matrix Q of transcript abundances (e.g., from liver tissue RNA-seq) for the same individuals with genotypes and phenotypes.

- Extended Model Specification: Use a Bayesian variable selection model that incorporates both SNP and transcript effects [32]:

y = 1μ + Xb + Zu + Wa + Qg + ewhere g is the vector of effects for transcripts, and other terms are as previously defined. Mixture priors as in Eqs. (2) and (3) from [32] are placed on both a and g. - MCMC and Variance Partitioning: Run the MCMC sampler. For each saved sample, compute the explained variance for SNPs,

var(Wa), and for transcripts,var(Qg). - Inferring eQTLs: Identify SNPs for which the effect (and the explained variance on a specific chromosome/region) substantially decreases or disappears when transcripts are included in the model. This indicates the SNP's effect is likely regulatory [32].

Performance and Practical Considerations

The choice of Bayesian model should be guided by the expected genetic architecture of the trait, which in turn influences the accuracy of genomic prediction and QTL discovery.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Bayesian and Other Models in Genomic Prediction

| Model | Reported Average Accuracy | Strengths | Weaknesses / Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| BayesR | 0.625 (Highest among tested models [30]) | Effective at modeling mixtures of effect sizes; high accuracy. | Computationally intensive. |

| BayesCÏ€ | 0.622 [30] | Infers sparsity (Ï€); good balance of performance and inference. | Computationally intensive. |

| GBLUP | 0.611 [30] | Fast, less biased, best computational efficiency. | Assumes an infinitesimal model, blurring QTL signals. |

| WGBLUP | 0.614-0.617 [30] | Incorporates prior SNP weights; can improve accuracy for some traits. | Performance gain is trait-dependent; can lose unbiasedness. |

| Machine Learning (SVR) | Up to 0.755 for type traits [30] | Can capture non-linear interactions; top performer for some traits. | Requires extensive hyperparameter tuning; computationally costly. |

The performance of these models is not universal. Bayesian alphabets generally excel for traits governed by a few QTLs with relatively larger effects and for highly heritable traits [29]. In contrast, GBLUP and other BLUP methods show robust performance for traits controlled by many small-effect QTLs [29]. Furthermore, as shown in a 2025 study on Holstein cattle, while advanced methods like BayesR and SVR can achieve the highest accuracies, they come at a significant computational cost, requiring on average more than six times the computational time of GBLUP [30]. This trade-off between accuracy, inferential power, and computational resources is a key practical consideration for researchers.

Figure 2: A decision guide for selecting a genomic model based on the expected genetic architecture of the target trait.

Bayesian alphabet models provide a powerful and flexible statistical framework for moving beyond prediction to the interpretation of genetic architecture. By employing specific prior distributions, methods like BayesB, BayesCÏ€, and BayesR allow researchers to infer critical features such as the number of QTLs, their genomic locations, and the magnitude of their effects. The integration of additional omics layers, such as transcriptome data, further enhances our ability to distinguish between different types of QTLs and understand the biological mechanisms linking genotype to phenotype. While computational demands and the inherent influence of priors require careful consideration, the continued development and application of these models are unequivocally advancing our capacity to dissect the genetic architecture of complex traits.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Bayesian Genomic Models

In genomic selection, the fundamental challenge lies in predicting complex phenotypes from a high-dimensional set of genetic markers where the number of predictors (p) vastly exceeds the number of observations (n). Bayesian methods address this problem by imposing specific prior distributions on marker effects, thereby enabling stable estimation and prediction. The choice of prior—whether t-distribution, Laplace, or various mixtures—directly influences how a model handles genetic architecture, balancing shrinkage and variable selection to optimize genomic prediction accuracy. These prior specifications form the foundation of what is known as the "Bayesian Alphabet" models, which have become indispensable tools in genomic selection research and applications across plant, animal, and human genetics [2] [19].

This protocol provides a comprehensive examination of key prior distributions used in Bayesian genomic selection models. We detail their theoretical foundations, implementation workflows, and performance characteristics across diverse genetic architectures, providing researchers with practical guidance for model selection and application in genomic prediction studies.

Theoretical Foundations of Bayesian Priors

Hierarchical Model Structure

Bayesian genomic prediction models typically employ a hierarchical structure where the observed phenotype is modeled as the sum of genetic and residual components. The core linear model takes the form:

[ yi = \mu + \sum{k=1}^p x{ik}\betak + e_i ]

where (yi) is the phenotype of individual (i), (\mu) is the overall mean, (x{ik}) is the genotype of individual (i) at marker (k), (\betak) is the effect of marker (k), and (ei) is the residual error term assumed to follow (N(0, \sigmae^2)) [33] [20]. The critical distinction between Bayesian Alphabet models lies in the prior specifications for the marker effects (\betak).

Classification of Priors

Priors in Bayesian Alphabet models can be categorized based on their shrinkage and selection properties:

- Shrinkage Priors: Continuously shrink marker effects toward zero, with varying degrees of heavy tails

- Variable Selection Priors: Include a point mass at zero, effectively selecting a subset of markers with non-zero effects

- Global-Local Priors: Employ both global shrinkage parameters and marker-specific local parameters to adapt to different effect sizes [20]

Table 1: Classification of Bayesian Alphabet Priors and Their Properties

| Prior Type | Model Examples | Shrinkage Pattern | Selection Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | GBLUP, BayesC0 | Uniform shrinkage | None |

| t-Distribution | BayesA | Heavy-tailed shrinkage | Continuous |

| Laplace | Bayesian LASSO | Intermediate shrinkage | Continuous |

| Point-Normal Mixture | BayesB, BayesC | Discrete shrinkage | Variable selection |

| Global-Local | BayesU, BayesHP, BayesHE | Adaptive shrinkage | Continuous |

Key Prior Distributions: Mathematical Formulations and Implementation

t-Distribution Priors (BayesA)

The BayesA model applies a scaled t-distribution prior to marker effects, implemented hierarchically:

[ \betak | \sigmak^2 \sim N(0, \sigmak^2) ] [ \sigmak^2 | \nu, S \sim \chi^{-2}(\nu, S) ]

This formulation results in marginal prior (p(\beta_k) \sim t(0, \nu, S)), a heavy-tailed distribution that allows large marker effects to escape severe shrinkage while strongly shrinking small effects toward zero [19] [2]. The degrees of freedom parameter (ν) controls tail thickness, with smaller values resulting in heavier tails. In practice, ν is often fixed at 4-5 degrees of freedom, while scale parameter S is estimated from the data.

Protocol 3.1: Implementing BayesA with MCMC

- Initialize parameters: Set (\betak = 0), (\sigmak^2 = 1), (\mu = \bar{y}), (\sigma_e^2 = \text{var}(y))

- Sample overall mean: (\mu | \text{else} \sim N\left(\frac{\sum{i=1}^n (yi - \sum x{ik}\betak)}{n}, \frac{\sigma_e^2}{n}\right))

- Sample marker effects: (\betak | \text{else} \sim N\left(\frac{\sum x{ik}rk}{\sum x{ik}^2 + \sigmae^2/\sigmak^2}, \frac{\sigmae^2}{\sum x{ik}^2 + \sigmae^2/\sigmak^2}\right)) where (rk = yi - \mu - \sum{j≠k} x{ij}\beta_j)

- Sample marker variances: (\sigmak^2 | \text{else} \sim \chi^{-2}\left(\nu + 1, \frac{\betak^2 + \nu S}{\nu + 1}\right))

- Sample residual variance: (\sigmae^2 | \text{else} \sim \chi^{-2}\left(n + \alpha, \frac{\sum ei^2 + \delta}{\alpha + n}\right)) with (ei = yi - \mu - \sum x{ik}\betak)

- Repeat steps 2-5 for adequate MCMC iterations (typically 20,000-50,000) after burn-in [19] [2]

Laplace Priors (Bayesian LASSO)

The Bayesian LASSO employs a double-exponential (Laplace) prior on marker effects:

[ p(\betak | \lambda) = \frac{\lambda}{2} \exp(-\lambda |\betak|) ]

This prior can be represented hierarchically as a scale mixture of normals:

[ \betak | \tauk^2 \sim N(0, \tauk^2) ] [ \tauk^2 | \lambda^2 \sim \text{Exp}\left(\frac{\lambda^2}{2}\right) ]

The Bayesian LASSO provides intermediate shrinkage between the normal and t-distribution priors, performing continuous variable selection without completely excluding markers from the model [19] [33]. The regularization parameter λ controls the degree of shrinkage and can be assigned a gamma hyperprior for estimation from data.

Protocol 3.2: Implementing Bayesian LASSO with Gibbs Sampling

- Initialize parameters: Set (\betak = 0), (\tauk^2 = 1), (\mu = \bar{y}), (\lambda^2 = 1), (\sigma_e^2 = \text{var}(y))

- Sample marker effects: (\betak | \text{else} \sim N\left(\frac{\sum x{ik}rk}{\sum x{ik}^2 + \sigmae^2/\tauk^2}, \frac{\sigmae^2}{\sum x{ik}^2 + \sigmae^2/\tauk^2}\right))

- Sample scale parameters: (\frac{1}{\tauk^2} | \text{else} \sim \text{Inverse-Gaussian}\left(\sqrt{\frac{\lambda^2\sigmae^2}{\beta_k^2}}, \lambda^2\right))

- Sample regularization parameter: (\lambda^2 | \text{else} \sim \text{Gamma}\left(p + 1, \frac{\sum \tau_k^2}{2}\right))

- Sample residual variance (if unknown): (\sigmae^2 | \text{else} \sim \chi^{-2}\left(n + \alpha, \frac{\sum ei^2 + \delta}{\alpha + n}\right))

- Repeat sampling for adequate MCMC iterations [19] [2]

Mixture Priors (BayesB, BayesC)

Mixture priors incorporate a point mass at zero to perform variable selection:

BayesB uses a point-t mixture prior: [ \beta_k | \pi, \nu, S \sim \begin{cases} 0 & \text{with probability } \pi \ t(0, \nu, S) & \text{with probability } 1-\pi \end{cases} ]

BayesC uses a point-normal mixture prior: [ \betak | \pi, \sigma\beta^2 \sim \begin{cases} 0 & \text{with probability } \pi \ N(0, \sigma_\beta^2) & \text{with probability } 1-\pi \end{cases} ]

These mixture models explicitly differentiate between markers with non-zero effects and those with no effect, effectively performing variable selection while estimating effects for selected markers [2] [19]. The proportion π of markers with zero effects can be fixed or estimated from data (e.g., BayesCπ).

Protocol 3.3: Implementing BayesCÏ€ with Gibbs Sampling

- Initialize parameters: Set (\betak = 0), (\deltak = 1) (indicator), (\pi = 0.5), (\mu = \bar{y}), (\sigma\beta^2 = \text{var}(y)/p), (\sigmae^2 = \text{var}(y))

- Sample indicator variables: (P(\deltak = 1 | \text{else}) = \frac{(1-\pi) \cdot N(\betak | 0, \sigma\beta^2)}{\pi \cdot \delta0 + (1-\pi) \cdot N(\betak | 0, \sigma\beta^2)})

- Sample marker effects for markers with (\deltak = 1): (\betak | \text{else} \sim N\left(\frac{\sum x{ik}rk}{\sum x{ik}^2 + \sigmae^2/\sigma\beta^2}, \frac{\sigmae^2}{\sum x{ik}^2 + \sigmae^2/\sigma_\beta^2}\right))

- Set (\betak = 0) for markers with (\deltak = 0)

- Sample mixture proportion: (\pi | \text{else} \sim \text{Beta}(p - \sum \deltak + a, \sum \deltak + b))

- Sample common variance: (\sigma\beta^2 | \text{else} \sim \chi^{-2}\left(\sum \deltak + \nu, \frac{\sum \betak^2 + \nu S}{\sum \deltak + \nu}\right))

- Sample residual variance: (\sigmae^2 | \text{else} \sim \chi^{-2}\left(n + \alpha, \frac{\sum ei^2 + \delta}{\alpha + n}\right))

- Repeat steps 2-7 for MCMC iterations [2]

Global-Local Priors (BayesU, BayesHP, BayesHE)

Recent developments include global-local priors that adaptively shrink markers based on their effects:

BayesU uses the Horseshoe prior: [ \betak | \lambdak, \tau \sim N(0, \lambdak^2 \tau^2) ] [ \lambdak \sim C^+(0, 1), \quad \tau \sim \text{flat} ]

where (\lambda_k) are local shrinkage parameters and (\tau) is a global shrinkage parameter [20].

BayesHP extends this with Horseshoe+ prior: [ \betak | \lambdak, \tau \sim N(0, \lambdak^2 \tau^2) ] [ \lambdak \sim C^+(0, \etak), \quad \etak \sim C^+(0, 1), \quad \tau \sim C^+(0, N^{-1}) ]

BayesHE uses a half-t distribution with unknown degrees of freedom for the local parameters, providing additional flexibility [20].

Performance Comparison Across Genetic Architectures

The optimal choice of prior depends heavily on the underlying genetic architecture of the target trait. Studies have systematically evaluated how different priors perform across varying heritability levels, QTL numbers, and effect size distributions.

Table 2: Performance of Bayesian Priors Across Different Genetic Architectures

| Genetic Architecture | Recommended Priors | Performance Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Highly Polygenic (Many small effects) | GBLUP, BayesC0, BayesHE | Normal priors perform well for highly polygenic traits; BayesHE showed robust performance across cattle and mouse traits [20] |

| Mixed Architecture (Few large, many small effects) | BayesB, BayesCÏ€, BayesU | Variable selection models outperform for traits with both large and small effect QTL; BayesU showed competitive performance in simulations [2] [20] |