Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS): A 2025 Guide to Functional Gene Validation

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers utilizing Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) for functional gene validation.

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS): A 2025 Guide to Functional Gene Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers utilizing Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) for functional gene validation. It covers the foundational mechanisms of VIGS, including its basis in post-transcriptional gene silencing and the role of viral suppressors. The guide details current methodological approaches with various viral vectors, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies to enhance silencing efficiency, and explores advanced applications and validation techniques. Aimed at scientists in plant biology and biotechnology, this review synthesizes recent advances to empower robust, high-throughput gene function analysis, particularly in non-model systems resistant to stable transformation.

Understanding VIGS: Core Principles and Mechanisms of RNA Silencing

Defining Virus-Induced Gene Silencing and Its Role in Reverse Genetics

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) is an RNA-mediated reverse genetics technology that has evolved into an indispensable approach for analyzing gene function in plants. This powerful technique downregulates endogenous genes by utilizing the plant's post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) machinery to prevent systemic viral infections. Based on recent advances, VIGS can now be employed as a high-throughput tool that induces heritable epigenetic modifications through transient knockdown of targeted gene expression. This article provides a comprehensive overview of VIGS molecular mechanisms, details optimized experimental protocols, and presents its expanding applications in functional genomics and crop improvement, positioning VIGS as a critical technology for functional validation research.

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing represents a sophisticated reverse genetics tool that enables researchers to rapidly determine gene function by selectively silencing target genes. The technology leverages plants' natural antiviral defense mechanisms—specifically post-transcriptional gene silencing—that degrade viral RNA in a sequence-specific manner. When recombinant viral vectors carrying fragments of plant genes are introduced into host plants, the defense machinery recognizes and degrades both viral RNA and homologous endogenous mRNA transcripts, resulting in targeted gene silencing [1] [2].

The significance of VIGS in modern functional genomics stems from its ability to overcome limitations associated with stable genetic transformation. Traditional approaches such as T-DNA insertion, chemical mutagenesis, and CRISPR/Cas9, while powerful, often involve labor-intensive processes, require stable transformation lines, and may be ineffective for studying essential genes that cause plant lethality when disrupted [3]. In comparison, VIGS offers a rapid, cost-effective alternative that does not depend on stable transformation, making it particularly valuable for plant species recalcitrant to genetic transformation, including many agriculturally important crops [2] [4].

The historical foundation of VIGS was established in 1995 when Kumagai et al. first used a Tobacco mosaic virus vector carrying a fragment of the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene from Nicotiana benthamiana to induce silencing, resulting in a characteristic photo-bleaching phenotype [2]. Since this pioneering demonstration, VIGS technology has expanded significantly, with vectors developed from numerous viruses and applications validated across diverse plant species including tomato, barley, soybean, cotton, pepper, and various woody plants [1] [2].

Molecular Mechanisms of VIGS

The biological basis of VIGS operates through the well-characterized mechanism of post-transcriptional gene silencing, which plants employ as an antiviral defense system. The process begins when a recombinant viral vector is introduced into the plant cell, triggering a cascade of molecular events [2]:

Viral Replication and dsRNA Formation: Following inoculation, the viral vector begins replicating within the host plant. During replication, double-stranded RNA molecules—common intermediates in viral replication—are generated [1] [2].

dicer-like Enzyme Processing: Cellular Dicer-like enzymes recognize and cleave these long double-stranded RNA molecules into small interfering RNAs of 21-24 nucleotides in length [1].

RISC Complex Formation: These siRNAs are incorporated into an RNA-induced silencing complex, with the siRNA serving as a guide sequence [1] [2].

Target mRNA Degradation: The RISC complex identifies and catalyzes the sequence-specific degradation of complementary mRNA molecules, including both viral transcripts and endogenous plant mRNAs with sufficient homology [1].

Recent research has revealed that VIGS can also induce transcriptional gene silencing through RNA-directed DNA methylation. In this advanced mechanism, the AGO complex interacts with target DNA molecules in the nucleus, causing transcriptional repression via DNA methylation at promoter regions. This epigenetic modification can lead to heritable gene silencing that persists across generations, significantly expanding VIGS applications beyond transient knockdown studies [1].

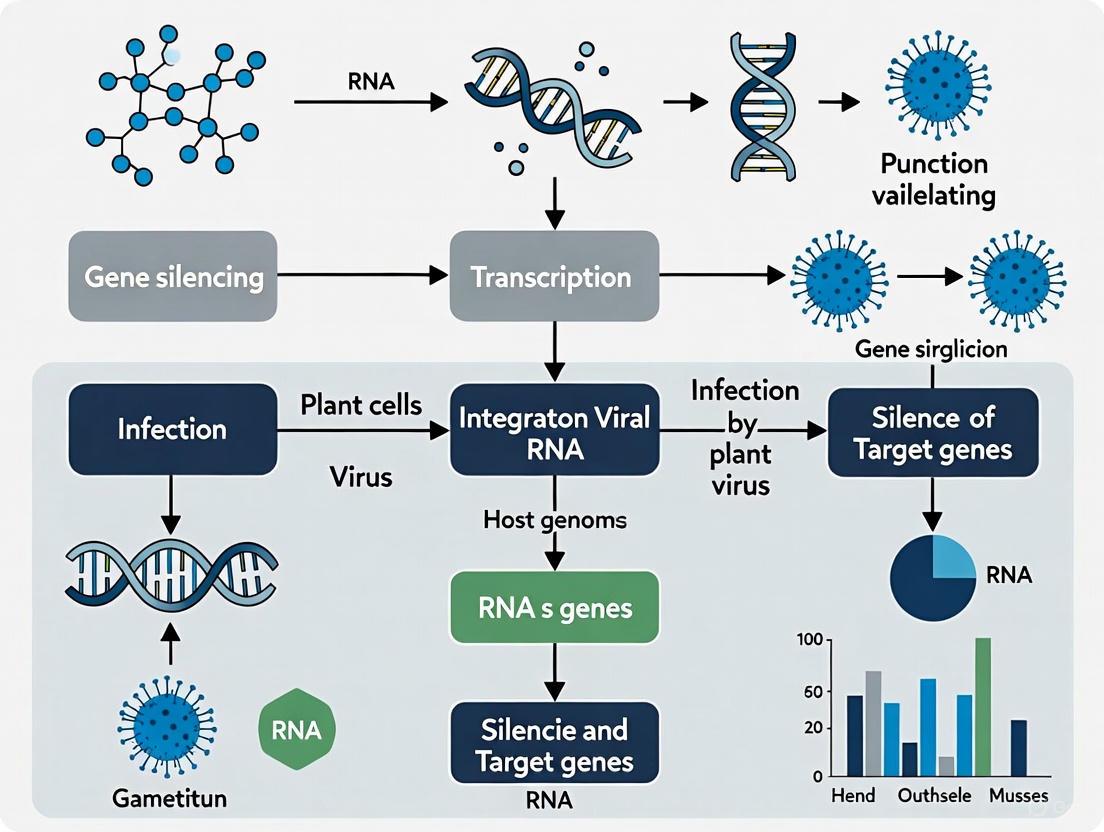

Figure 1: Molecular Mechanisms of VIGS. The process begins with viral vector introduction, leading to dsRNA formation and siRNA processing. These siRNAs guide both post-transcriptional silencing through mRNA degradation and transcriptional silencing via DNA methylation.

VIGS Vector Systems

The effectiveness of VIGS experiments depends significantly on selecting appropriate viral vectors, which are broadly categorized into RNA viruses, DNA viruses, and satellite virus-based systems. Each vector type offers distinct advantages and limitations based on host range, silencing efficiency, persistence, and symptom development [2].

RNA Virus-Based Vectors

Vectors derived from RNA viruses are characterized by cytoplasmic replication mediated by virus-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. These vectors typically offer efficient systemic spread and rapid gene suppression but may induce pronounced viral symptoms that complicate phenotypic analysis [2].

Tobacco Rattle Virus is one of the most versatile and widely used VIGS systems, particularly for Solanaceae plants. TRV features a bipartite genome requiring two vectors: TRV1 encodes replicase and movement proteins, while TRV2 contains the capsid protein and multiple cloning site for inserting target sequences. TRV demonstrates broad host range, efficient systemic movement including meristematic tissues, and mild infection symptoms [2].

Tobacco Mosaic Virus represents the first viral vector successfully used for VIGS. While historically significant, TMV vectors may cause more severe symptoms compared to TRV [1].

Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus has been successfully deployed in cucurbit species. Recent research has established CGMMV-based VIGS systems in Luffa acutangula (ridge gourd), demonstrating efficient silencing of phytoene desaturase and tendril development genes [4].

Cucumber Fruit Mottle Mosaic Virus has been engineered into the pCF93 vector for functional genomics studies in watermelon. This system successfully identified eight candidate genes involved in male sterility out of 38 tested, demonstrating its utility for high-throughput screening [5].

DNA Virus-Based Vectors

DNA virus-based vectors, primarily geminiviruses such as Cotton leaf crumple virus and African cassava mosaic virus, replicate in the nucleus and offer prolonged silencing duration. These vectors are particularly valuable for species where RNA vectors show limited efficiency [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major VIGS Vector Systems

| Vector Type | Example | Host Range | Silencing Duration | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Virus | Tobacco Rattle Virus | Broad (Solanaceae, Arabidopsis, etc.) | Medium to Long | Mild symptoms, meristem penetration | Bipartite genome requires two components |

| RNA Virus | Tobacco Mosaic Virus | Moderate | Medium | Historical significance, well-characterized | Potentially severe symptoms |

| RNA Virus | Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus | Cucurbits | Medium | Effective for cucurbit species | Limited host range |

| DNA Virus | Geminiviruses | Variable | Long | Extended silencing period | More complex vector design |

Established VIGS Protocols

Successful implementation of VIGS requires careful optimization of inoculation methods, plant growth conditions, and vector delivery techniques. Below are detailed protocols for established VIGS methodologies.

Agrobacterium-Mediated Leaf Infiltration

This represents the most common VIGS delivery method, particularly for dicot plants [4]:

Reagent Preparation:

- Transform recombinant pTRV2 and pTRV1 vectors into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains (GV3101 or GV2260).

- Culture positive colonies in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics (kanamycin 50 μg/mL, rifampicin 25 μg/mL) and 20 μM acetosyringone.

- Resuspend bacterial pellets in infiltration buffer to final OD600 = 0.8-1.0.

- Incubate bacterial suspensions in the dark at room temperature for 3-4 hours.

Inoculation Procedure:

- Select plants at the 2-4 true leaf stage for inoculation.

- Using a needleless syringe, infiltrate the bacterial suspension into the abaxial side of leaves.

- Create small punctures in leaves prior to infiltration to enhance uptake if necessary.

- Maintain inoculated plants under high humidity for 24-48 hours post-infiltration.

- Grow plants at optimal temperatures (typically 18-22°C) to enhance silencing efficiency.

Root Wounding-Immersion Method

This efficient method developed for Solanaceae and other species enables high-throughput inoculation [3]:

Procedure:

- Grow plants until 3-4 true leaves develop (approximately 3 weeks old).

- Carefully remove plants from soil and wash roots with pure water.

- Using a sterilized blade, remove approximately one-third of the root system lengthwise.

- Immerse wounded roots in TRV1:TRV2 mixed Agrobacterium suspension (OD600 = 0.8) for 30 minutes.

- Reportplants in fresh soil and maintain under standard growth conditions.

Validation: This method achieves 95-100% silencing efficiency for PDS in N. benthamiana and tomato, with GFP tracking confirming systemic viral movement from roots to leaves and stems [3].

Cotyledon Node Method for Soybean

Soybean presents unique challenges due to its thick cuticle and dense trichomes. This optimized protocol addresses these limitations [6]:

Procedure:

- Surface-sterilize soybean seeds and soak in sterile water until swollen.

- longitudinally bisect seeds to obtain half-seed explants.

- Immerse fresh explants in Agrobacterium suspension containing pTRV1 or pTRV2 derivatives for 20-30 minutes.

- Culture inoculated explants on appropriate medium.

- Monitor infection efficiency via GFP fluorescence, with effective rates exceeding 80%.

Application: This system successfully silenced GmPDS, GmRpp6907, and GmRPT4 genes with 65-95% efficiency in soybean [6].

Figure 2: General VIGS Experimental Workflow. The process involves vector construction, Agrobacterium preparation, plant inoculation, incubation, and final analysis of silencing effects.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of VIGS requires specific reagents and materials optimized for different plant systems. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for establishing robust VIGS protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for VIGS Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples | Optimal Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| pTRV1/pTRV2 Vectors | TRV bipartite system; TRV1 for replication proteins, TRV2 for target gene insertion | Solanaceae, Arabidopsis, Soybean | OD600 = 0.8-1.0 in infiltration buffer |

| pCF93 Vector | CFMMV-based vector for cucurbit species | Watermelon, Cucumber | 35S promoter-driven expression |

| pV190 Vector | CGMMV-based vector for cucurbit species | Ridge gourd, Bottle gourd | OD600 = 0.8-1.0 with BamHI insertion site |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 | Vector delivery into plant cells | Most dicot species | Resuspension in 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MES, 200 μM AS |

| Acetosyringone | Induces Agrobacterium virulence genes | Enhances T-DNA transfer | 150-200 μM in infiltration buffer |

| Infiltration Buffer | Medium for Agrobacterium suspension during inoculation | All infiltration methods | 10 mM MgClâ‚‚, 10 mM MES (pH 5.6-5.7) |

| Phytoene Desaturase Gene | Visual marker for silencing efficiency | Validation across species | 200-300 bp fragment sufficient for silencing |

Applications in Functional Genomics

VIGS has become an indispensable tool for functional genomics across diverse plant species, enabling rapid characterization of genes involved in development, stress responses, and metabolic pathways.

Crop Improvement Applications

Disease Resistance Gene Validation: VIGS has successfully identified numerous genes involved in plant defense mechanisms. In soybean, TRV-based VIGS silenced the GmRpp6907 rust resistance gene and GmRPT4 defense-related gene, confirming their roles in disease resistance [6]. Similarly, tomato SITL5 and SITL6 disease-resistance genes were silenced via root wounding-immersion, resulting in decreased disease resistance [3].

Abiotic Stress Tolerance: VIGS has elucidated genes involved in responses to temperature, salt, and osmotic stresses. In pepper, VIGS identified genes governing resistance to abiotic factors, facilitating development of stress-tolerant cultivars [2].

Fruit Quality and Development: VIGS applications in pepper have identified genes controlling fruit color, biochemical composition, and pungency [2]. The technology has also been employed to study genes regulating plant architecture and development [2].

Male Sterility Studies: In watermelon, a CFMMV-based VIGS system screened 38 candidate genes related to male sterility, identifying eight that produced sterile male flowers with abnormal stamens and no pollen when silenced [5].

High-Throughput Functional Screening

The scalability of VIGS makes it particularly valuable for high-throughput functional genomics. The technology enables simultaneous characterization of multiple gene functions without stable transformation. In cucurbits, VIGS systems have been established for rapid assessment of gene function in species recalcitrant to genetic transformation [4]. Similarly, the root wounding-immersion method allows large-scale functional genome screening in plants [3].

Epigenetic Applications

Recent advances have expanded VIGS applications to include induction of heritable epigenetic modifications. Studies demonstrate that VIGS can initiate RNA-directed DNA methylation at target loci, leading to transgenerational epigenetic silencing. Research by Bond et al. (2015) showed that TRV:FWAtr infection leads to transgenerational epigenetic silencing of the FWA promoter sequence in Arabidopsis [1]. This epigenetic modification persists across generations without continued presence of the viral vector, opening new possibilities for crop improvement through epigenetic engineering [1].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Successful VIGS implementation requires careful attention to several critical factors that influence silencing efficiency:

Plant Growth Conditions: Temperature significantly impacts silencing efficiency, with most systems performing optimally at 18-22°C. Higher temperatures often reduce silencing efficiency, while lower temperatures enhance it. Proper light intensity (16h light/8h dark photoperiod) and humidity control (approximately 70% relative humidity) are also crucial [4] [3].

Agroinoculum Parameters: The concentration of Agrobacterium suspension requires optimization for each plant species. While N. benthamiana typically responds well to OD600 = 0.8-1.0, higher concentrations may cause leaf necrosis. For tomato, OD600 = 1.5 may provide better infection efficiency [3].

Developmental Stage: Plant age at inoculation significantly affects silencing efficiency. Most species achieve optimal results when inoculated at the 2-4 true leaf stage. Earlier inoculation may improve silencing but increases mortality risk, while later inoculation may reduce efficiency [4].

Insert Design: Target gene fragment selection critically influences silencing efficiency. Fragments of 200-300 nucleotides with minimal self-complementarity typically work best. The insert should share 85-100% sequence identity with the target gene and avoid conserved domains shared with unrelated genes to prevent off-target effects [4] [6].

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing has established itself as a powerful and versatile reverse genetics tool that continues to evolve with expanding applications in functional genomics. The technology's unique ability to provide rapid, high-throughput gene characterization without requiring stable transformation makes it indispensable for modern plant research. Recent advances in vector development, delivery methods, and understanding of epigenetic modifications have further enhanced VIGS utility for both basic research and applied crop improvement.

As genomic sequencing technologies continue to generate vast amounts of data for diverse plant species, VIGS will play an increasingly critical role in bridging the gap between sequence information and biological function. The integration of VIGS with emerging technologies like virus-induced genome editing and multi-omics approaches promises to accelerate functional genomics studies and facilitate development of improved crop varieties with enhanced agronomic traits.

Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing (PTGS) is an evolutionarily conserved RNA-mediated defense mechanism that plants employ to protect against viral pathogens [1]. This sequence-specific RNA degradation system recognizes and cleaves invasive RNA molecules, providing immunity against foreign genetic elements. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) represents a powerful reverse genetics approach that creatively exploits this natural antiviral pathway [7]. Researchers have harnessed this plant defense mechanism by engineering viral vectors to carry fragments of host genes, effectively "tricking" the plant's silencing machinery to target its own endogenous mRNAs for degradation [2] [1].

The foundational principle of VIGS lies in the plant's innate immune response: when a virus infects a plant, the host recognizes double-stranded RNA replication intermediates and processes them into small interfering RNAs that guide the destruction of complementary viral RNA sequences [2]. By inserting a fragment of a plant gene into a viral vector, this defense system can be redirected to silence the corresponding host gene, enabling functional characterization without the need for stable transformation [7]. Since its initial demonstration in 1995 using Tobacco mosaic virus to silence the phytoene desaturase gene in Nicotiana benthamiana, VIGS has evolved into a versatile functional genomics tool applicable to a wide range of plant species [2] [1].

The methodology offers several distinct advantages over traditional transformation-based approaches. VIGS enables rapid gene function analysis, with results typically observable within 2-4 weeks post-inoculation [7]. It bypasses the need for stable transformation, making it particularly valuable for plant species recalcitrant to genetic transformation [2] [6]. Additionally, VIGS can silence multi-copy genes and genes that would cause embryo lethality in stable knockouts, while also offering the potential to target multiple members of gene families to address functional redundancy [7]. These characteristics have established VIGS as an indispensable tool for high-throughput functional validation in plant genomics research.

Molecular Mechanisms of PTGS and VIGS

The molecular machinery of PTGS operates through a precisely coordinated sequence of events that begins with recognition of double-stranded RNA molecules. During viral infection, or when a recombinant VIGS vector is introduced, the plant's Dicer-like enzymes recognize and cleave long double-stranded RNA into 21-24 nucleotide small interfering RNAs [2] [1]. These siRNAs are then incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex, where they serve as guides for sequence-specific identification and cleavage of complementary target mRNAs [1]. The catalytic component of RISC, typically an Argonaute protein, mediates the endonucleolytic cleavage of the target transcript, leading to gene silencing [2].

A critical feature of this silencing mechanism is its systemic nature. The silencing signal, likely involving siRNAs, can move cell-to-cell through plasmodesmata and systemically through the phloem, resulting in silencing throughout the plant [7]. This amplification and movement of the silencing signal ensures that even tissues not directly infected by the viral vector can exhibit gene silencing. Secondary siRNAs produced through the activity of host RNA-directed RNA polymerases enhance VIGS maintenance and dissemination, reinforcing the silencing effect [1].

Table 1: Key Molecular Components of the PTGS Pathway

| Component | Structure/Function | Role in VIGS |

|---|---|---|

| Dicer-like (DCL) Enzymes | RNase III-type nucleases | Processes viral dsRNA into 21-24 nt siRNAs |

| Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs) | 21-24 nucleotide RNA duplexes | Guides sequence-specific mRNA degradation |

| Argonaute (AGO) Proteins | Core components of RISC complex with slicer activity | Mediates target mRNA cleavage using siRNA as guide |

| RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases (RDRs) | Synthesizes dsRNA using siRNA-primed target mRNA | Amplifies silencing signal; generates secondary siRNAs |

| RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC) | Multi-protein complex with AGO at core | Executes sequence-specific mRNA degradation |

Beyond the cytoplasmic PTGS mechanism, VIGS can also induce epigenetic modifications in the nucleus through RNA-directed DNA methylation [1]. When siRNAs derived from the VIGS vector are transported to the nucleus, they can guide DNA methyltransferases to homologous genomic sequences, leading to transcriptional gene silencing through promoter methylation [1]. This heritable epigenetic modification represents an additional layer of gene regulation that can be exploited for functional genomics and plant breeding applications.

VIGS Vector Systems and Applications

Viral Vector Selection Criteria

The choice of an appropriate viral vector is paramount for successful VIGS experimentation, with several critical factors influencing selection. Different viral vectors exhibit varying host ranges, silencing efficiencies, and symptom severity, necessitating careful consideration based on the target plant species and experimental objectives [2]. The most effective VIGS vectors typically demonstrate broad host range, efficient systemic movement, minimal disease symptoms, capability to target meristematic tissues, and stability with inserted gene fragments [2] [7]. To date, VIGS has been successfully implemented using vectors based on at least 50 different viruses, enabling application across diverse plant species including model organisms, crops, and woody plants [2] [1].

Among RNA viruses, Tobacco Rattle Virus has emerged as one of the most versatile and widely adopted systems, particularly for Solanaceae species [2]. TRV possesses a bipartite genome requiring two vectors: TRV1 encodes replicase and movement proteins, while TRV2 contains the coat protein gene and serves as the insertion site for target sequences [2]. Other prominent RNA viral vectors include Potato Virus X, Tobacco Mosaic Virus, and Cucumber Mosaic Virus, each with distinct advantages and limitations [7]. DNA viruses, particularly those in the Geminiviridae family such as Cotton Leaf Crumple Virus and African Cassava Mosaic Virus, have also been successfully engineered as VIGS vectors, offering alternative replication mechanisms and potentially different host compatibility [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Major VIGS Vector Systems

| Vector Type | Virus Examples | Host Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Viruses | Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) | Broad (Solanaceae, Arabidopsis, etc.) | Efficient systemic movement; minimal symptoms | Bipartite genome requires two constructs |

| Potato Virus X (PVX) | Moderate (Solanaceous species) | High insert stability; strong silencing | Can cause noticeable symptoms in some hosts | |

| Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) | Very broad | Extensive host range | Can induce severe symptoms | |

| DNA Viruses | Geminiviruses (CLCrV, ACMV) | Dependent on specific virus | Long-lasting silencing; different replication | Smaller insert capacity |

| Satellite Virus-Based | Satellite Tobacco Mosaic Virus | Varies with helper virus | Can enhance silencing efficiency | Requires helper virus |

Applications in Functional Genomics

VIGS has been extensively employed to characterize genes involved in diverse biological processes, significantly advancing our understanding of plant gene function. In pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), VIGS has facilitated the identification of genes governing critical agronomic traits including fruit quality attributes such as color, biochemical composition, and pungency [2]. The technology has been particularly valuable for dissecting disease resistance pathways, enabling researchers to validate the function of resistance genes and defense-related signaling components against bacterial, oomycete, and insect pathogens [2] [6].

The application of VIGS extends to abiotic stress tolerance, with successful silencing of genes involved in responses to temperature extremes, salt stress, and osmotic stress [2]. In soybean, a recently optimized TRV-VIGS system achieved 65-95% silencing efficiency for target genes including the rust resistance gene GmRpp6907 and defense-related gene GmRPT4 [6]. Beyond these applications, VIGS has proven instrumental in studying plant architecture and development, metabolic pathways, and hormone signaling networks across numerous plant species [2] [7].

Emerging applications include the use of VIGS for inducing heritable epigenetic modifications through RNA-directed DNA methylation [1]. This approach enables the creation of stable epigenetic alleles with altered gene expression patterns, offering potential for crop improvement without permanent genetic changes. Additionally, the integration of VIGS with high-throughput screening platforms and multi-omics technologies represents a powerful future direction for systematic functional genomics in plants [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TRV-Based VIGS Protocol for Dicotyledonous Plants

The TRV-based VIGS system represents one of the most robust and widely applicable methods for gene silencing in dicotyledonous plants. The protocol begins with the cloning of a 200-500 bp fragment of the target gene into the TRV2 vector using standard restriction enzyme-based or ligation-independent cloning techniques [6]. The selected fragment should exhibit minimal self-complementarity and share limited sequence similarity with non-target genes to ensure specificity. The recombinant TRV2 plasmid and the complementary TRV1 plasmid are then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains such as GV3101 [6].

For agroinfiltration, bacterial cultures are grown overnight in appropriate antibiotic-containing media, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in infiltration buffer to a final optical density at 600 nm of 0.5-2.0 [2]. The resuspension buffer typically contains 10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, and 150 μM acetosyringone, with the latter enhancing T-DNA transfer efficiency. Equal volumes of TRV1 and recombinant TRV2 agrobacterial suspensions are mixed and incubated at room temperature for 2-4 hours before infiltration [6]. For plants with thick cuticles or dense trichomes that impede liquid penetration, such as soybean, optimized methods involving cotyledon node immersion for 20-30 minutes have demonstrated significantly higher infection efficiency compared to conventional misting or direct injection approaches [6].

Optimization Strategies and Efficiency Evaluation

Multiple factors significantly influence VIGS efficiency and require careful optimization for different plant species and growth conditions. The developmental stage of the plant at inoculation is critical, with most species exhibiting highest susceptibility at the 2-4 leaf stage [2]. Environmental parameters including temperature, humidity, and photoperiod must be controlled, as temperature particularly affects both viral replication and RNA silencing machinery activity [2]. Post-inoculation maintenance at 20-22°C for the first few days often enhances silencing efficiency, followed by transfer to standard growth conditions [2].

The concentration of the agroinoculum represents another crucial parameter, with OD₆₀₀ typically optimized between 0.3-2.0 depending on the plant species and infiltration method [2] [6]. For challenging plant species, the incorporation of viral suppressors of RNA silencing such as P19 or HC-Pro can temporarily inhibit the plant's silencing machinery, allowing enhanced viral accumulation and subsequently stronger silencing [2]. However, this approach requires careful timing to balance initial viral accumulation with subsequent silencing establishment.

Evaluation of silencing efficiency incorporates both phenotypic and molecular assessments. For visible markers like phytoene desaturase, photobleaching provides a clear visual indicator of successful silencing [6]. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR remains the gold standard for quantifying target gene transcript reduction, with effective silencing typically achieving 70-95% reduction in mRNA levels [6]. Additional validation methods include Western blotting for protein level assessment when suitable antibodies are available, and histological analyses for developmental phenotypes [2].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common VIGS Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No silencing phenotype | Low infectivity; inappropriate insert; plant resistance | Optimize agroinfiltration method; verify insert orientation and size; use younger plants |

| Patchy or inconsistent silencing | Uneven vector distribution; environmental fluctuations | Improve infiltration technique; maintain stable growth conditions |

| Severe viral symptoms | High viral titer; hypersensitive response | Dilute agroinoculum; try different vector; adjust temperature |

| Silencing not sustained | Viral clearance; plant recovery | Use more stable vector system; optimize plant growth conditions |

| Non-specific phenotypes | Off-target effects; viral toxicity | BLAST insert for uniqueness; include multiple controls |

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of VIGS requires a comprehensive toolkit of specialized reagents and biological materials. The core components include viral vectors, Agrobacterium strains, plant genotypes, and various molecular biology reagents specifically optimized for VIGS applications.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for VIGS Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors | TRV1/TRV2 system; PVX; BPMV; CLCrV | Delivery of target gene fragments; choice depends on host species |

| Agrobacterium Strains | GV3101; LBA4404; AGL1 | Mediate plant transformation; different strains vary in efficiency |

| Plant Genotypes | Nicotiana benthamiana; specific crop cultivars | Model plants or target species; susceptibility varies |

| Antibiotics | Kanamycin; Rifampicin; Gentamicin | Selection for plasmid maintenance and agrobacterial strains |

| Induction Compounds | Acetosyringone (150-200 μM) | Enhances T-DNA transfer during agroinfiltration |

| Infiltration Buffers | 10 mM MES, 10 mM MgClâ‚‚ (pH 5.6) | Maintains bacterial viability and facilitates infiltration |

| Cloning Reagents | Restriction enzymes; ligases; Gateway system | Insertion of target fragments into viral vectors |

For reliable and reproducible results, proper preparation and quality control of these reagents is essential. Agrobacterium strains should be verified for compatibility with the binary vector system and tested for virulence. Viral vectors require validation through sequencing of insert junctions and functionality testing with positive control genes like PDS. Plant materials should be selected based on known susceptibility to the chosen viral vector and grown under optimized conditions to ensure consistent developmental stages at inoculation [2] [6].

Specialized reagents for efficiency enhancement include viral suppressors of RNA silencing such as P19, which can be co-infiltrated with the VIGS vectors to temporarily boost viral accumulation [2]. For molecular verification of silencing, primers should be designed to amplify regions outside the fragment used for VIGS construct generation to avoid amplification from the viral vector itself. High-quality RNA extraction kits capable of handling plant polysaccharides and secondary metabolites are particularly important for accurate quantification of silencing efficiency [6].

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful reverse genetics tool for rapid functional validation of plant genes. This technology exploits the plant's innate RNA interference (RNAi) machinery to achieve sequence-specific downregulation of target genes [2] [1]. The core molecular components enabling this process—Dicer-like enzymes (DCLs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)—function collaboratively as an adaptive immune system against viral pathogens [8] [9]. Understanding the precise roles and interactions of these players is fundamental for optimizing VIGS efficiency and expanding its applications in functional genomics and crop improvement. This application note details the mechanisms, protocols, and reagents for investigating these key components within the VIGS framework, providing researchers with practical methodologies for advanced functional gene validation.

Molecular Mechanisms of VIGS

The VIGS process initiates when a recombinant viral vector, carrying a fragment of the host target gene, is introduced into the plant cell via Agrobacterium-mediated delivery or other inoculation methods [2] [6]. The plant's RNA polymerase II transcribes the viral genome, producing double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) replicative intermediates [2] [1]. These dsRNA molecules are recognized as foreign by the plant's antiviral defense system, triggering the RNAi cascade. The core mechanism involves the cleavage of these long dsRNAs by DICER-like enzymes into 21–24 nucleotide small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [8] [1]. These siRNAs are then loaded into the RISC complex, where an Argonaute (AGO) protein uses the siRNA as a guide to identify and cleave complementary endogenous mRNA targets, leading to post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) [1] [9] [10]. Simultaneously, RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRs) can amplify the silencing signal by using the cleaved RNAs as templates to synthesize secondary dsRNAs, which are subsequently processed into secondary siRNAs, enabling systemic spread of silencing throughout the plant [8] [9].

Core Molecular Players

Dicer-like (DCL) Enzymes

Dicer-like enzymes belong to the RNase III family and initiate the RNAi pathway by processing long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) precursors into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [9]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, four DCL proteins (DCL1-4) perform specialized, yet partially overlapping, functions in different small RNA pathways. DCL1 is primarily involved in microRNA (miRNA) biogenesis, processing hairpin structures from primary miRNA transcripts [9]. DCL2 processes viral dsRNAs and endogenous natural antisense transcripts, generating 22-nucleotide siRNAs [8]. DCL3 produces 24-nucleotide heterochromatic siRNAs (hc-siRNAs) involved in RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) and transcriptional gene silencing [8] [1]. DCL4 generates 21-nucleotide trans-acting siRNAs (tasiRNAs) and secondary siRNAs, playing a crucial role in the systemic spread of silencing [9].

In antiviral defense and VIGS, DCL2 and DCL4 are primarily responsible for processing viral dsRNAs into 22-nt and 21-nt virus-derived siRNAs (vsiRNAs), respectively [8]. These vsiRNAs guide the silencing complex to target and degrade complementary viral RNAs. DCL3 also contributes to antiviral immunity through the RdDM pathway, which can silence viral DNA genomes [8]. The specific DCL enzymes engaged in VIGS can vary depending on the viral vector and host plant species, influencing the efficiency and persistence of gene silencing.

Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

Small interfering RNAs are the effector molecules of the silencing pathway, providing the sequence specificity for target recognition. These 21-24 nucleotide RNA duplexes are characterized by 2-nucleotide overhangs at their 3' ends and 5' phosphate groups [9]. During VIGS, two primary classes of siRNAs are generated: primary siRNAs, derived from the direct DCL-mediated processing of the viral dsRNA, and secondary siRNAs, produced through an amplification mechanism involving RDRs [8] [9].

Secondary siRNA amplification requires host RDRs (particularly RDR6 in Arabidopsis), which use the cleaved target mRNA as a template to synthesize new dsRNA molecules [8]. These dsRNAs are subsequently processed by DCLs into secondary siRNAs, enabling a robust and systemic silencing response that can spread throughout the plant. This amplification mechanism is crucial for achieving strong and persistent silencing phenotypes in VIGS experiments.

RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC)

The RNA-induced silencing complex is the catalytic engine of the RNAi pathway, responsible for executing sequence-specific mRNA cleavage or translational repression. The core component of RISC is an Argonaute (AGO) protein, which binds the small RNA guide strand and slices complementary target mRNAs using its PIWI domain, which exhibits RNase H-like activity [10].

Plants possess multiple AGO proteins with specialized functions. In Arabidopsis, AGO1 is the primary effector for miRNA-mediated silencing and certain siRNA pathways, while AGO2 plays a crucial role in antiviral defense and is preferentially loaded with viral siRNAs [8] [10]. AGO4, AGO6, and AGO9 are primarily involved in the RdDM pathway, associating with 24-nt siRNAs to direct transcriptional silencing [10]. During RISC assembly, the siRNA duplex is loaded onto an AGO protein, followed by unwinding and removal of the passenger strand. The mature RISC complex then scans cellular mRNAs for complementarity to the guide siRNA, leading to endonucleolytic cleavage of perfectly matched targets.

Table 1: Core Components of the Plant RNAi Machinery in VIGS

| Component | Key Family Members | Primary Function in VIGS | Characteristic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dicer-like (DCL) Enzymes | DCL2, DCL4, DCL3 | Processes viral dsRNA into vsiRNAs | RNase III family, dsRNA-specific endonucleases |

| Argonaute (AGO) Proteins | AGO1, AGO2, AGO4 | Core RISC component, executes mRNA cleavage | PAZ and PIWI domains, siRNA binding capability |

| siRNA Classes | Primary siRNAs (21-22nt), Secondary siRNAs (21-24nt) | Sequence-specific targeting of complementary mRNAs | 5' phosphate groups, 2-nt 3' overhangs |

| RNA-dependent RNA Polymerases (RDRs) | RDR1, RDR2, RDR6 | Amplifies silencing signal via secondary siRNA production | RNA-dependent RNA synthesis |

Experimental Protocols

Analyzing siRNA Profiles During VIGS

Principle: Characterizing the size, abundance, and origin of vsiRNAs is essential for understanding silencing efficiency and dynamics. This protocol uses high-throughput sequencing to profile small RNAs from VIGS-treated tissues.

Reagents and Equipment:

- TRIzol reagent for total RNA extraction

- Small RNA library preparation kit (e.g., NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep Set)

- PEG solution (for small RNA precipitation)

- 15% denaturing urea polyacrylamide gel

- Sequencing platform (Illumina preferred)

- Bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100)

Procedure:

- Plant Material Preparation: Infiltrate plant tissues (e.g., N. benthamiana leaves) with TRV-based VIGS vectors carrying your target gene fragment [2] [6]. Include empty vector controls.

- Total RNA Extraction: At 14-21 days post-infiltration, harvest systemic leaves showing silencing phenotypes. Homogenize tissue in TRIzol, extract total RNA following manufacturer's protocol.

- Small RNA Enrichment: Precipitate small RNAs (<200 nt) by adding 5% PEG 8000/0.5 M NaCl to total RNA, incubate on ice for 30 min, and centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 min [8].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Use 1 μg of enriched small RNA for library preparation according to kit instructions. Size-select 18-30 nt fragments from a 15% urea-PAGE gel. Validate library quality using Bioanalyzer before sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Trim adapters using Cutadapt

- Map reads to both plant genome and viral vector using ShortStack

- Classify siRNAs by size (21-nt vs. 22-nt vs. 24-nt)

- Analyze siRNA distribution along target gene and viral genome

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low siRNA yield: Optimize PEG precipitation step; verify RNA integrity

- High adapter dimer formation: Improve size selection stringency

- Insufficient vsiRNAs: Confirm viral infection efficiency by RT-PCR

Functional Characterization of DCL Enzymes in VIGS

Principle: Using genetic mutants to dissect the contributions of specific DCL enzymes to VIGS efficiency and siRNA biogenesis.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Arabidopsis dcl2, dcl3, dcl4 mutant seeds (ABRC)

- TRV-based VIGS vectors

- SYBR Green RT-PCR kits

- siRNA northern blot reagents

Procedure:

- Plant Genotyping: Confirm homozygous T-DNA insertion mutants for dcl2, dcl3, and dcl4 by PCR-based genotyping.

- VIGS Inoculation: Inoculate 2-week-old wild-type and mutant plants with TRV vectors carrying fragments of marker genes (e.g., PDS for photobleaching) [2] [6]. Use at least 15 plants per genotype.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Monitor and document silencing phenotypes (e.g., photobleaching for PDS) weekly for 4 weeks. Score silencing efficiency as percentage of plants showing clear phenotypes.

- Molecular Analysis:

- Extract total RNA from systemic leaves at 21 dpi

- Perform RT-qPCR to quantify target gene expression knockdown

- Conduct northern blotting with specific probes to detect 21-nt, 22-nt, and 24-nt vsiRNAs

- Data Interpretation: Compare silencing efficiency and vsiRNA profiles between wild-type and mutant plants to determine the contributions of specific DCLs.

Table 2: Expected VIGS Efficiency in Arabidopsis DCL Mutants

| Genotype | Expected Silencing Efficiency | Primary siRNA Alterations | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Strong systemic silencing (65-95%) [6] | 21-nt and 22-nt vsiRNAs present | Standard VIGS experiments |

| dcl2 mutant | Reduced early systemic silencing | Diminished 22-nt vsiRNAs | Studying spatial aspects of silencing |

| dcl4 mutant | Significantly compromised silencing | Absence of 21-nt vsiRNAs | Understanding systemic spread |

| dcl2/dcl4 double mutant | Severely compromised silencing | Drastic reduction in all vsiRNAs | Confirming DCL-dependent mechanisms |

Assessing RISC Activity and Specificity

Principle: This protocol evaluates RISC formation and activity through molecular and biochemical approaches during VIGS.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Anti-AGO1 and anti-AGO2 antibodies

- Protein A/G agarose beads

- In vitro transcriptions system

- Radiolabeled ATP (γ-32P)

- Non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels

Procedure:

- Plant Tissue Collection: Harvest VIGS-treated and control tissues at peak silencing (typically 14-21 dpi). Flash-freeze in liquid N2.

- RISC Immunoprecipitation: Grind tissue to fine powder, extract protein in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitors). Incubate 500 μg total protein with anti-AGO1 or anti-AGO2 antibodies for 2h at 4°C, then with Protein A/G beads for 1h [10].

- RNA Extraction from RISC: Isolve RNA from immunoprecipitated complexes using TRIzol, and analyze associated small RNAs by RT-qPCR or northern blotting.

- In Vitro RISC Activity Assay:

- Generate 32P-labeled in vitro transcripts complementary to the VIGS target

- Incubate with immunoprecipitated RISC complexes in cleavage buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM KOAc, 2 mM MgOAc, 0.5 mM DTT) for 2h at 25°C

- Resolve products on 8% denaturing urea-PAGE gels

- Visualize cleavage products by autoradiography

- Data Analysis: Quantify RISC activity by measuring the ratio of cleaved to uncleaved substrate. Compare AGO1 vs. AGO2 activities in VIGS-treated tissues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for VIGS Molecular Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIGS Vectors | TRV (Tobacco Rattle Virus), BPMV (Bean Pod Mottle Virus), CLCrV (Cotton Leaf Crumple Virus) [2] [6] | Delivery of target gene fragments to trigger silencing | TRV: broad host range; BPMV: optimal for legumes |

| Agrobacterium Strains | GV3101, LBA4404 | Delivery of viral vectors into plant cells | GV3101 offers high transformation efficiency [6] |

| DCL Mutants | Arabidopsis dcl2, dcl3, dcl4 T-DNA lines | Genetic analysis of siRNA biogenesis pathways | Double mutants may show developmental defects |

| AGO Antibodies | Anti-AGO1, Anti-AGO2 (polyclonal) | Immunoprecipitation of RISC complexes | Verify cross-reactivity for specific plant species |

| Small RNA Sequencing Kits | NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep Set | Comprehensive siRNA profiling | Include size selection steps for clean libraries |

| Target Prediction Tools | Sfold ΔGdisruption, DSSE, and AIS parameters [11] | In silico prediction of effective target sequences | Lower ΔGdisruption correlates with higher efficiency |

| Acebutolol Hydrochloride | Acebutolol Hydrochloride | High-purity Acebutolol Hydrochloride, a selective beta-adrenergic blocker. Ideal for cardiovascular and pharmacological research. For Research Use Only (RUO). | Bench Chemicals |

| Cyclizine dihydrochloride | Cyclizine dihydrochloride, CAS:5897-18-7, MF:C18H24Cl2N2, MW:339.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Visualization of VIGS Experimental Workflow

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a pivotal reverse genetics tool, revolutionizing functional genomics by enabling rapid interrogation of gene function without the need for stable transformation. This technique leverages the plant's innate antiviral RNA interference machinery, where recombinant viruses carrying plant gene fragments trigger sequence-specific degradation of complementary mRNA targets. From its initial discovery in tobacco plants exhibiting unexpected pigmentation patterns post-viral infection, VIGS has evolved into a versatile platform with proven efficacy across diverse plant species, including recalcitrant crops and perennial woody plants [3] [12]. The historical trajectory of VIGS reflects continuous methodological refinement, expanding its utility from fundamental research to applied agricultural science.

The Evolution of VIGS Applications

The application landscape of VIGS has diversified significantly from its initial discovery. The technology has been successfully adapted for functional gene validation in plant defense mechanisms, stress tolerance, metabolic engineering, and developmental biology. Key advancements include the establishment of robust VIGS systems in previously challenging species such as soybean (Glycine max), tea oil camellia (Camellia drupifera), and various Solanaceae crops [6] [12]. Modified VIGS systems have now been implemented across numerous plant families including Brassicaceae, Solanaceae, Gramineae, Cucurbitaceae, Asteraceae, Leguminosae, Orchidaceae, and Malvaceae [3]. The technology has proven particularly valuable for characterizing disease-resistance genes (R-genes), with successful silencing of genes like SITL5 and SITL6 in tomato resulting in decreased disease resistance [3].

Table 1: Historical Expansion of VIGS Host Range

| Year | Plant Species | Family | Key Achievement | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Nicotiana benthamiana | Solanaceae | Established TRV-based VIGS | 95-100% [3] |

| 2004 | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Solanaceae | Cross-species PDS silencing | 95-100% [3] |

| 2012 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Brassicaceae | Adapted for model plant | Successful [3] |

| 2024 | Soybean (Glycine max) | Leguminosae | Cotyledon node delivery | 65-95% [6] |

| 2024 | Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) | Solanaceae | Root wounding-immersion | Successful [3] |

| 2025 | Tea oil camellia (Camellia drupifera) | Theaceae | Recalcitrant woody plant | ~93.94% [12] |

Established VIGS Methodologies

Root Wounding-Immersion Method

A significant methodological advancement came with the development of the root wounding-immersion technique, which enables high-efficiency VIGS across multiple plant species [3]. This protocol involves carefully standardized steps that ensure reproducible results:

Plant Material Preparation: Seedlings with 3-4 true leaves (approximately 3 weeks old) are carefully removed from soil and roots are cleansed with pure water to remove soil impurities [3].

Root Wounding: A disinfected leaf knife is used to remove precisely one-third of the root length longitudinally, creating entry points for viral vector infiltration [3].

Agrobacterium Preparation: Agrobacterium GV1301 strains containing pTRV1 and pTRV2 vectors are cultured in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics (50 μg/mL kanamycin, 25 μg/mL rifampicin) at 28°C for 2 days. The infiltration solution is prepared containing 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MES (pH 5.6), and 150 μM acetosyringone, with the culture resuspended to OD₆₀₀ = 0.8 [3].

Inoculation Approaches: Two immersion protocols are employed:

- Concurrent Inoculation: TRV1 and TRV2 solutions are mixed and roots immersed for 30 minutes

- Successive Inoculation: Roots immersed sequentially in TRV1 (15 minutes) then TRV2 (15 minutes) [3]

Post-Inoculation Care: Treated seedlings are transplanted and maintained under optimal growth conditions (16 hours light at 28°C/8 hours darkness at 20°C) [3].

This method achieves remarkable silencing efficiency of 95-100% for phytoene desaturase (PDS) in N. benthamiana and tomato, while successfully silencing PDS homologs in pepper, eggplant, and Arabidopsis thaliana [3].

Cotyledon Node Method for Soybean

Soybean presents particular challenges for VIGS due to its thick cuticle and dense leaf trichomes. An optimized cotyledon node method has been developed to overcome these limitations [6]:

Explant Preparation: Surface-sterilized soybeans are soaked in sterile water until swollen, then longitudinally bisected to create half-seed explants [6].

Agrobacterium Infection: Fresh explants are immersed for 20-30 minutes in Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 suspensions containing pTRV1 or pTRV2-GFP derivatives [6].

Efficiency Validation: On the fourth day post-infection, fluorescence microscopy confirms successful transformation, with transverse sections showing >80% of cells exhibiting successful infiltration [6].

This approach achieves effective infectivity efficiency exceeding 80%, reaching up to 95% for specific soybean cultivars like Tianlong 1 [6].

Pericarp Cutting Immersion for Woody Plants

For recalcitrant woody species like Camellia drupifera, researchers have developed a specialized pericarp cutting immersion technique [12]:

Plant Material Selection: Fruits are collected at specific developmental stages (279 days post-pollination) for optimal silencing efficiency [12].

Vector Construction: Target genes (CdCRY1 and CdLAC15) are cloned into pNC-TRV2 vectors, a modified version of pTRV2, with careful selection of 200-300 bp target-specific fragments to ensure silencing specificity [12].

Agrobacterium Preparation: Cultures are grown in YEB medium containing antibiotics (25 μg/mL kanamycin, 50 μg/mL rifampicin) and induced with acetosyringone until OD₆₀₀ reaches 0.9-1.0 [12].

Infiltration: Multiple approaches including peduncle injection, direct pericarp injection, pericarp cutting immersion, and fruit-bearing shoot infusion are evaluated, with pericarp cutting immersion demonstrating highest efficiency (~93.94%) [12].

This method enables functional analysis in tissues previously considered challenging for genetic studies, with optimal silencing effects observed at specific capsule developmental stages (~69.80% for CdCRY1 at early stage, ~90.91% for CdLAC15 at mid stage) [12].

Table 2: Comparative Efficiency of VIGS Delivery Methods

| Delivery Method | Target Species | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal OD₆₀₀ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root Wounding-Immersion | N. benthamiana, Tomato, Pepper, Eggplant, A. thaliana | High efficiency (95-100%), Suitable for young seedlings, Batch processing | Root disturbance, Sterility critical | 0.8 [3] |

| Cotyledon Node | Soybean (G. max) | Bypasses thick cuticle, High transformation (>80%), Cultivar-specific optimization | Requires sterile tissue culture, Explant preparation | Not specified [6] |

| Pericarp Cutting Immersion | Tea oil camellia (C. drupifera) | Effective for lignified tissues, Developmental stage optimization | Specialized to fruit tissues, Seasonal dependence | 0.9-1.0 [12] |

| Leaf Infiltration | N. benthamiana | Established protocol, Direct visualization | Species-dependent efficiency, Leaf damage | 1.5 for tomato [3] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of VIGS relies on carefully standardized research reagents and vectors that ensure reproducibility across experiments and plant species.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VIGS Implementation

| Reagent/Vector | Composition/Description | Function in VIGS | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRV Vectors (pTRV1/pTRV2) | Tobacco Rattle Virus-based binary vectors | pTRV1: RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; pTRV2: Carrier for target gene insert | Mild symptoms, wide host range, efficient spread [3] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | GV1301, GV3101 | Delivery vehicle for TRV vectors | Virulence, plasmid compatibility, antibiotic resistance [3] [6] |

| Induction Medium | 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MES (pH 5.6), 150-200 μM acetosyringone | Activates Agrobacterium virulence genes | Acetosyringone concentration critical for efficiency [3] [12] |

| Antibiotic Selection | Kanamycin (50 μg/mL), Rifampicin (25-50 μg/mL) | Maintains plasmid integrity, controls bacterial contamination | Concentration varies by Agrobacterium strain [3] [12] |

| Target Gene Fragments | 200-500 bp gene-specific sequences | Determines silencing specificity | Must have <40% similarity to non-target genes [12] |

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Successful VIGS implementation requires careful attention to several technical parameters that significantly impact silencing efficiency. Environmental conditions play a crucial role, with research indicating that low temperature and low humidity can increase VIGS silencing efficiency [3]. Furthermore, the concentration of the infiltration solution considerably affects gene silencing, with OD₆₀₀ > 1 causing N. benthamiana leaf necrosis, while OD₆₀₀ = 1.5 of Agrobacterium results in good infection effects in tomatoes [3].

The duration of silencing represents another critical consideration. Studies have confirmed that TRV-VIGS inoculated through agrodrench application or leaf infiltration can persist for 2 years or more, enabling extended phenotypic observation [3]. However, the potential for off-target effects necessitates careful fragment selection, with bioinformatic tools like the SGN VIGS Tool essential for identifying unique target sequences [12].

Visualizing VIGS Workflows

VIGS Experimental Workflow

The historical trajectory of VIGS, from its serendipitous discovery in tobacco to its current status as a versatile functional genomics tool, demonstrates remarkable methodological evolution. The development of specialized inoculation techniques—including root wounding-immersion, cotyledon node transformation, and pericarp cutting immersion—has systematically expanded VIGS applications across previously challenging plant species. These protocols, supported by standardized reagent systems and optimized parameters, enable researchers to address fundamental questions in plant biology with unprecedented efficiency and precision. As VIGS continues to evolve, its integration with emerging genome editing technologies promises to further accelerate crop improvement and functional gene validation in diverse plant systems.

Functional genomics is dedicated to understanding the complex relationships between gene sequence and biological function, providing the foundational knowledge required for modern plant breeding and genetic engineering [2]. In the post-genomic era, where sequencing technologies routinely generate vast amounts of data, the critical challenge has shifted from gene discovery to gene function characterization [2] [14]. Several powerful techniques have been developed to address this challenge, including Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS), stable genetic transformation, and genome-editing systems like CRISPR/Cas9 [2] [15] [16]. Each method offers distinct advantages and suffers from specific limitations, making their appropriate selection crucial for successful research outcomes.

VIGS has emerged as a particularly flexible and rapid alternative for gene functional analysis, especially in species that are difficult to transform [2] [12]. This technique leverages the plant's innate RNA interference (RNAi) machinery, using recombinant viral vectors to deliver gene fragments and trigger systemic, sequence-specific suppression of endogenous gene expression [2]. The resulting phenotypic changes enable researchers to infer gene function. This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of VIGS against other mainstream functional genomics tools, with detailed experimental protocols and resource guidelines to assist researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their functional validation studies.

Comparative Analysis of Functional Genomics Tools

The selection of a functional genomics tool involves careful consideration of multiple parameters, including technical feasibility, timeframe, cost, and desired experimental outcome. The table below provides a structured comparison of VIGS, stable transformation, and CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of major functional genomics tools

| Feature | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Stable Transformation (RNAi/OE) | CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) via viral delivery of target dsRNA [2] | Stable genomic integration of T-DNA for RNAi or overexpression [6] | Precise DNA cleavage and repair leading to gene knockout or editing [16] |

| Nature of Modification | Transient knockdown | Stable, heritable knockdown or overexpression | Stable, heritable knockout or precise mutation |

| Development Timeframe | Weeks (e.g., 2-3 weeks for phenotype) [6] [17] | Months to years [6] | Months to a year (excluding transgene elimination) [15] |

| Technical Complexity & Cost | Relatively low; avoids tissue culture [12] | High; requires efficient transformation and regeneration protocols [6] | High; requires transformation and often complex molecular characterization [16] |

| Key Advantage | Bypasses stable transformation; rapid screening; applicable to recalcitrant species [2] [12] | Stable, predictable phenotypes; suitable for long-term studies | Permanent, precise genetic changes; can create null alleles |

| Primary Limitation | Transient and variable silencing efficiency; potential off-target effects [2] | Genotype-dependent transformation efficiency; lengthy process [6] | Off-target mutations; complex regulatory landscape for transgene-free plants [15] |

| Ideal Use Case | High-throughput functional screening, studies in transformation-recalcitrant species [2] [12] | Generation of stable lines for detailed phenotypic analysis | Functional analysis of genes requiring complete knockout or specific alleles |

Key Advantages and Limitations in Context

VIGS stands out for its speed and ability to bypass stable transformation. Researchers can proceed from gene sequence to functional data in a matter of weeks, as demonstrated in soybean where silencing phenotypes for genes like GmPDS were observed within 21 days post-inoculation [6]. This makes it an unparalleled tool for high-throughput reverse genetics screens. Furthermore, VIGS is often the only viable functional genomics tool for perennial woody plants and other recalcitrant species with low transformation efficiency, such as Camellia drupifera [12] and pepper [2].

However, the limitations of VIGS are significant. Its effects are transient and can be variable, with silencing efficiency ranging from 65% to 95% and being influenced by factors like plant genotype, developmental stage, agroinfiltration methodology, and environmental conditions [2] [6]. The silencing is also not heritable, which prevents its use in studying gene function across generations. In contrast, stable transformation and CRISPR/Cas9 produce heritable modifications, making them essential for breeding applications [15] [16].

CRISPR/Cas9 technology offers the unique advantage of creating precise, permanent mutations, allowing for the analysis of true null alleles and the engineering of specific nucleotide changes [16]. This is critical for studying functionally redundant gene families in polyploid crops like rapeseed, where multiple homologous copies must be simultaneously mutated to reveal phenotypes [16]. A major drive in CRISPR/Cas9 development is the creation of transgene-free edited plants, which are deregulated in many countries and face fewer commercial hurdles than traditional GMOs [15].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of functional genomics tools relies on a suite of specialized reagents and vectors. The following table details key materials required for VIGS experiments.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for VIGS experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TRV-based Vectors (e.g., pTRV1, pTRV2) | Bipartite RNA virus system; TRV1 encodes replication proteins, TRV2 carries the target gene insert for silencing [2] | Most widely used VIGS vector; effective in Solanaceae, Arabidopsis, and some legumes [2] [6] |

| All-in-One Vectors (e.g., VS, VS2) | Single T-DNA vectors containing all viral genomes, simplifying Agrobacterium preparation and improving co-delivery [17] | Streamlines high-throughput work; available for CLCrV (VS) and TRV (VS2) [17] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens (e.g., GV3101) | Disarmed bacterial strain used to deliver viral T-DNA vectors into plant cells via agroinfiltration [6] [12] | Standard delivery method; requires optimization of optical density (OD600) and incubation conditions |

| Marker Gene VIGS Constructs (e.g., PDS, CLA) | Vectors targeting genes like Phytoene Desaturase (PDS) or Cloroplastos alterados (CLA) that produce visible phenotypes (photobleaching) to validate silencing efficiency [6] [17] | Critical positive control for optimizing VIGS protocols in new species or conditions |

| Viral Suppressors of RNAi (VSRs) (e.g., P19, C2b) | Co-expressed proteins that temporarily inhibit the plant's RNAi machinery, potentially enhancing VIGS efficiency [2] | Use requires careful optimization to avoid severe viral symptoms |

Detailed VIGS Experimental Protocol

The following workflow outlines a standard TRV-based VIGS protocol, adaptable for various plant species.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Vector Construction and Clone Preparation

- Insert Design: Select a 200-500 bp fragment of the target gene with low similarity to other genes in the genome to ensure specificity. Online tools like the SGN VIGS Tool can assist in design [12]. Recent advances show that even very short inserts of 24-32 nt (vsRNAi) can be effective when designed using comparative genomics [18].

- Cloning: Clone the target fragment into the multiple cloning site of the TRV2 vector (or equivalent) using restriction digestion or recombination-based cloning [6] [17]. The final construct is then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains like GV3101.

Step 2: Agrobacterium Culture Preparation

- Inoculate a single colony of Agrobacterium harboring both TRV1 and the recombinant TRV2 vectors into YEB medium containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin, rifampicin) and 10 mM MES [12].

- Incubate at 28°C with shaking (200-240 rpm) for 24-48 hours until the OD600 reaches approximately 0.9-1.0 [6] [12].

- Centrifuge the culture and resuspend the pellet in an infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, 200 µM acetosyringone). Adjust the final OD600 to an optimal concentration, typically between 0.5 and 2.0, which must be determined empirically for each plant species [2].

- Incubate the resuspended culture in the dark at room temperature for 2-4 hours before inoculation.

Step 3: Plant Inoculation The inoculation method must be adapted to the plant species and tissue type.

- For tender leaves (e.g., N. benthamiana): Use a needleless syringe to infiltrate the agrobacterial suspension directly into the abaxial side of leaves [2].

- For seedlings or recalcitrant tissues (e.g., soybean, camellia capsules): Methods like cotyledon node immersion or pericarp cutting immersion have proven highly effective. For soybean, bisecting swollen, sterilized seeds and immersing the fresh explants for 20-30 minutes achieved an infection efficiency of over 80% [6]. For woody Camellia drupifera capsules, pericarp cutting immersion achieved an infiltration efficiency of ~94% [12].

Step 4: Post-Inoculation Management and Analysis

- Maintain inoculated plants under controlled environmental conditions. Temperature, humidity, and photoperiod are critical factors that significantly impact silencing efficiency and must be optimized [2].

- Observe plants for the development of phenotypic changes, which typically begin to appear in systemic tissues 2 to 4 weeks post-inoculation [6] [17].

- Validate silencing efficiency phenotypically (if a visible phenotype is expected) and molecularly using quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) to measure the reduction in target gene transcript levels [6].

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

The utility of VIGS is expanding beyond simple gene knockdown through integration with other cutting-edge technologies.

VIGS for High-Throughput Screening: The development of "all-in-one" viral vectors that simplify Agrobacterium preparation and the establishment of proto-VIGS—a method using protoplasts and a dual-luciferase reporter to screen for efficient silencing fragments within 2 days—are paving the way for high-throughput functional genomics [17]. This dramatically accelerates the pre-screening of candidate genes.

Integration with Genome Editing (VIGE): Virus-Induced Genome Editing (VIGE) represents a powerful synergy of these technologies. Viral vectors are used to deliver CRISPR/Cas components, enabling transient genome editing without stable transformation [17] [15]. This approach holds great promise for generating transgene-free edited plants in a single generation, bypassing the labor-intensive and genotype-dependent tissue culture process [15]. While challenges such as limited cargo capacity of viral vectors and efficient editing in meristematic tissues remain, solutions involving smaller Cas proteins and mobile elements are being actively pursued [15].

Multi-Omics and Data Integration: The future of functional genomics lies in the integration of VIGS with multi-omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics). For instance, transcriptome-wide analysis of plants subjected to VIGS can reveal global changes in gene expression and functional networks, providing a systems-level understanding of gene function [18] [14]. This integrated approach will be crucial for deciphering complex agronomic traits and accelerating the breeding of climate-resilient crops [2] [14].

VIGS, stable transformation, and CRISPR/Cas9 are complementary tools in the functional genomics toolkit. VIGS is unmatched for its speed and applicability to recalcitrant species, making it ideal for initial, high-throughput gene validation. Stable transformation provides stable and heritable modifications for deep phenotypic analysis, while CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise genetic engineering for creating novel alleles and studying gene function at the DNA level.

The choice of tool should be guided by the experimental goal, the target species, and available resources. For rapid functional screening, particularly in non-model plants, VIGS is often the most pragmatic starting point. The ongoing development of more efficient vectors, refined protocols for difficult species, and hybrid technologies like VIGE ensure that VIGS will continue to be a cornerstone of plant functional genomics, playing a vital role in linking gene sequences to biological function and accelerating crop improvement.

VIGS in Practice: Vector Systems and Experimental Applications

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful reverse genetics tool for rapid functional validation of plant genes. This technology leverages the plant's innate RNA interference machinery, using recombinant viral vectors to carry host gene fragments and initiate sequence-specific mRNA degradation. The choice of viral vector is paramount to experimental success, as it determines host range, silencing efficiency, durability, and the ability to target specific tissues. This article provides a comparative analysis of four prominent VIGS vectors—Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV), Broad Bean Wilt Virus 2 (BBWV2), Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV), and geminiviruses—to guide researchers in selecting the optimal system for their functional genomics projects.

Vector Comparison and Selection Guide

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of major VIGS vectors.

| Vector | Genome Type | Key Advantages | Primary Hosts/Applications | Silencing Onset & Duration | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) | Bipartite RNA | Broad host range; efficient in meristems; mild symptoms [2] [19] | Solanaceae (pepper, tomato), legumes, woody plants [2] [6] | 2-3 weeks; several weeks [6] [20] | Not suitable for all monocots |

| Broad Bean Wilt Virus 2 (BBWV2) | Bipartite RNA | Effective in specific dicots like spinach [21] | Spinach, broad bean [21] | Information Missing | Narrower host range; can cause severe symptoms like yellowing and wrinkling [21] |

| Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) | Tripartite RNA | Very wide host range (>1000 species) [21] | Diverse hosts, including spinach [21] | Information Missing | Can cause severe symptoms (e.g., spinach blight), masking phenotypes [21] |

| Geminiviruses | Single-stranded DNA | Nuclear replication; potential for persistent silencing [22] | Dicots and monocots; genome editing applications [23] [22] | Information Missing | Often phloem-limited; more complex clone development [23] |

Table 2: Quantitative protocol parameters for VIGS across different plant systems.

| Plant System | Optimal Agrobacterium OD600 | Optimal Plant Stage | Recommended Inoculation Method | Reported Silencing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean | 0.8 - 1.0 [6] | Swollen half-seed explants [6] | Cotyledon node immersion (20-30 min) [6] | 65% - 95% [6] |

| Walnut | 1.5 [20] | Seedlings with fully unfolded cotyledons [20] | Cotyledon injection (two injections recommended) [20] | ~48% [19] |

| Atriplex canescens | 0.8 [24] | Germinated seeds (1-3 cm radicle) [24] | Vacuum infiltration (0.5 kPa, 10 min) [24] | ~16.4% [24] |

| Chinese Jujube | 1.5 [20] | Seedlings with fully unfolded cotyledons [20] | Cotyledon injection (two injections recommended) [20] | 65% (phenotypic observation) [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

TRV-Based VIGS in Soybean

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a VIGS experiment.

Protocol:

- Vector Construction: Amplify a 255-400 bp fragment of the target gene (e.g., GmPDS for a visual control) and clone it into the multiple cloning site of the pTRV2 vector using appropriate restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoRI and XhoI) [6]. The pTRV1 plasmid contains genes for viral replication and movement [2].

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Introduce the recombinant pTRV2 and the pTRV1 plasmids separately into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Culture individual colonies in YEP liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin, rifampicin) until mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6-0.8) [24].

- Agroinoculum Preparation: Pellet the bacterial cultures by centrifugation and resuspend them in an infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 200 µM acetosyringone, 10 mM MgCl₂). Mix the TRV1 and TRV2 suspensions in equal volumes to the final OD600 specified for the plant system (see Table 2) and incubate in the dark for 3 hours [24].

- Plant Inoculation: For soybean, use the optimized cotyledon node method. Bisect sterilized, pre-swollen seeds to create half-seed explants. Immerse these explants in the agroinoculum for 20-30 minutes [6]. For other species, methods like vacuum infiltration of germinated seeds (Atriplex) [24] or direct injection into cotyledons (jujube, walnut) [19] [20] are effective.

- Post-Inoculation Care: Rinse explants, transplant into vermiculite or soil, and maintain plants in a greenhouse or growth chamber with controlled temperature (e.g., 22-24°C) and photoperiod (e.g., 16h light/8h dark) [24] [20].

- Efficiency Validation: Visually monitor for photobleaching in PDS-silenced controls. Quantify silencing efficiency by measuring the relative transcript abundance of the target gene in silenced versus control plants using qRT-PCR [24] [20].

Geminivirus Infectious Clone Application

Protocol:

- Inoculum and Plant Preparation: Resuspend agrobacterium carrying the geminivirus infectious clone in infiltration buffer to an OD600 of 0.1-0.3 [23].

- Inoculation: For best results, use stem injection on young seedlings. This method helps overcome barriers to infection present in mature leaves [23].

- Critical Considerations: Plant age is a decisive factor. Younger seedlings are generally more susceptible. The choice of agrobacterium strain and stringent control over environmental conditions (light, temperature) are also crucial for achieving high infection rates [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for establishing a VIGS system.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VIGS Vectors | Engineered viral genomes for delivering plant gene fragments. | pTRV1/pTRV2 (TRV system) [2] [6]; pBY (Geminivirus system) [22]. |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Delivers the T-DNA containing the viral vector into plant cells. | GV3101 is widely used for its high efficiency in many species [6] [24] [20]. |

| Infiltration Buffer | Solution for suspending agrobacteria and facilitating infection. | Typically contains 10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, and 200 µM acetosyringone to induce virulence [24]. |

| Marker Gene | Visual reporter for quickly assessing silencing efficiency. | Phytoene desaturase (PDS): silencing causes photobleaching [19] [24]. Chloroplastos alterados 1 (CLA1): silencing causes albino phenotypes [20]. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | For molecular validation and quantification of gene silencing. | Essential to confirm knockdown of target gene mRNA levels (40-80% reduction is typical) [24] [20]. |

| Bendamustine Hydrochloride | Bendamustine Hydrochloride | Bendamustine hydrochloride is a bifunctional alkylating agent for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| L-erythro-Chloramphenicol | Chloramphenicol|Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic for Research |

Selecting the optimal VIGS vector is a critical, hypothesis-driven decision. The TRV-based system is often the preferred starting point for dicots due to its broad host range, mild symptoms, and well-established protocols. For recalcitrant species or specific applications like genome editing, geminivirus vectors offer a potent alternative. Ultimately, successful functional validation depends on aligning the vector's strengths with the target plant's biology and the specific research question. The standardized protocols and comparative data provided here serve as a foundational guide for researchers to deploy VIGS technology effectively.