Alternative Splicing and Protein Diversity: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the mechanisms by which alternative splicing generates proteomic diversity, a process crucial for normal development and cellular homeostasis.

Alternative Splicing and Protein Diversity: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the mechanisms by which alternative splicing generates proteomic diversity, a process crucial for normal development and cellular homeostasis. We explore the foundational biology of splicing regulation, including the roles of cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors like SR proteins and hnRNPs. The review covers cutting-edge computational and experimental methods for splicing analysis, including the use of AlphaFold2 for predicting structural consequences of splice variants. We address the significant challenge of interpreting splice-disruptive variants in disease and discuss emerging RNA-targeted therapeutic strategies, such as antisense oligonucleotides, that correct aberrant splicing. Finally, we examine evolutionary perspectives on splicing across species and outline future directions for translating splicing research into clinical applications, offering insights highly relevant to researchers and drug development professionals in the biomedical field.

The Fundamental Mechanisms of Alternative Splicing in Proteome Expansion

RNA splicing represents a critical post-transcriptional process in eukaryotic gene expression, enabling a single gene to produce multiple mRNA variants and significantly increasing proteomic diversity. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of RNA splicing mechanisms, from fundamental constitutive splicing to the complex regulation of alternative isoforms. We detail the molecular machinery of the spliceosome, the cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors governing splicing regulation, and the experimental methodologies driving discovery in this field. Within the broader context of protein diversity research, we highlight how alternative splicing contributes to tissue-specific functions and disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. The document further presents quantitative analyses of splicing types, structured methodologies for splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTL) analysis, and visualizations of key pathways, providing researchers and drug development professionals with both foundational knowledge and advanced tools for investigating splicing mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA is an essential mechanism for increasing the complexity of proteins in humans, causing diverse expression of transcriptomes and proteomes in a tissue-specific manner [1]. This process allows a single gene to generate multiple mRNA variants through different combinations of exons, following the removal of introns [2]. Current data indicate that each transcript of protein-coding genes contains approximately 11 exons and produces 5.4 mRNAs on average [1]. The significance of alternative splicing is underscored by its prevalence—more than 95% of human genes undergo splicing in a developmental, tissue-specific, or signal transduction-dependent manner [3]. This process represents a central element in gene expression that influences nearly every aspect of protein function, including interactions between proteins and ligands, nucleic acids or membranes, protein localization, and enzymatic properties [3].

The functional implications of alternative splicing extend across biological systems, with higher eukaryotes exhibiting a higher proportion of alternatively spliced genes, indicating its prominent role in evolution [3]. Alternative splicing mediates diverse biological processes throughout an organism's lifespan and plays significant functional roles in species differentiation, genome evolution, and the development of functionally complex tissues with diverse cell types [3]. The precision and diversity of alternative splicing events are governed by multiple factors, including the strength of splice sites, the concentration and combination of enhancing and silencing splicing factors, chromatin modifications, and RNA secondary structures [1].

Molecular Mechanisms of Splicing

Spliceosome Assembly and Function

The spliceosome, a dynamic and massive macromolecular complex, executes the precise mechanism of RNA splicing. This complex comprises five small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) and hundreds of associated proteins known as small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) [1] [2]. The spliceosome undergoes stepwise assembly through a series of complexes (E, A, B, and C) in a highly regulated process [1]:

- Complex E: U1 snRNP binds to the 5'-splice site (SS) GU dinucleotide, while splicing factor 1 (SF1) and U2AF65 bind to the branch point site (BPS) and polypyrimidine tract (PPT), respectively.

- Complex A: U2 snRNP base-pairing interacts with the BPS, displacing SF1.

- Complex B: The complex recruits U4/U6/U5 tri-snRNP, with U5 snRNP binding to 3'-SS and U6 snRNP binding to U2 snRNP. U1 and U4 snRNPs are released during this step.

- Complex C: Formation of this complex leads to two transesterification steps where the intron is folded into a lariat and the 5'-SS is cleaved. The two exons are subsequently joined, and the lariat is released with snRNPs recycled for further splicing cycles [1].

This assembly process facilitates the two transesterification reactions that define splicing chemistry. The first reaction involves the 2'-OH of the branch point adenosine attacking the 5'-splice site to create a lariat and free the 5'-exon. In the second reaction, the 3'-OH of the 5'-exon attacks the 3'-splice site to join the exons and release the intron lariat [4]. While the overall reaction is isoenergetic and requires no phosphoryl transfer to the pre-mRNA, the spliceosome consumes both ATP and GTP to power essential conformational rearrangements during assembly, catalysis, and disassembly [4].

cis-Acting Regulatory Elements

The boundaries between exons and introns are defined by specific consensus sequences that guide spliceosome recognition and catalysis [1] [3]:

- 5'-splice site (5'-SS): Highly conserved GU dinucleotide sequence at the intron/exon boundary

- 3'-splice site (3'-SS): Highly conserved AG nucleotide sequence at the exon/intron boundary

- Branch point sequence (BPS): Located 18-40 nucleotides upstream of the 3'-SS, containing the adenosine residue that forms the lariat structure

- Polypyrimidine tract (PPT): A pyrimidine-rich region critical in recognizing the 3'-SS

The decision to remove or retain specific exons depends on short nucleotide sequences called cis-acting elements, which function as binding sites for regulatory proteins [1]. These elements are categorized based on their location and function:

- Exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs): Bind positive regulatory factors to promote exon inclusion

- Exonic splicing silencers (ESSs): Bind negative regulatory factors to promote exon skipping

- Intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs): Enhance splicing from intronic positions

- Intronic splicing silencers (ISSs): Suppress splicing from intronic positions [1] [3]

These cis-acting elements function additively, with enhancing elements playing dominant roles in constitutive splicing and silencers being relatively more important in controlling alternative splicing [3].

trans-Acting Splicing Factors

The regulation of alternative splicing is mediated by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) known as trans-acting factors or splicing factors. The two major families of cellular RNA-binding proteins participating in splicing regulation are serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) [1] [2].

SR Proteins typically contain RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and serine/arginine-rich domains (RS domains) that facilitate their function in splicing regulation [1]. SR proteins mediate the interaction between U1 snRNP and the 5'-splice site and recruit U2 snRNP to the 3'-splice site [1]. They often cooperate with other positive splicing factors to form enhancing complexes, such as TRA2, SRRM1, and SRRM2 [1]. The function of SR protein family members depends on phosphorylation regulation by Cdc2-like kinases (CLKs) and SR-specific protein kinases (SRPKs) [2]. SR proteins also participate in post-splicing activities, including mRNA nuclear export, nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), and mRNA translation [3].

hnRNPs generally function as splicing repressors that bind to ESSs and ISSs to inhibit spliceosome assembly [1] [2]. hnRNPs are highly conserved from nematodes to mammals and have several critical roles in pre-mRNA maturation [3]. Their function often involves binding to ESSs to the exclusion of SR proteins or looping out pre-mRNA to sequester exons from the rest of the transcript [3].

SR proteins and hnRNP families generally have opposing effects during the selection of alternative splice sites and exons, often acting in a competitive manner [1]. For example, in the β-tropomyosin gene, splicing of exon 6B depends on a G-rich intronic sequence that can act as either an enhancer or silencer. ASF/SF2 and SC35 (SR proteins) bind to this sequence and stimulate splicing of exon 6B, whereas hnRNP A1 competitively disrupts their interaction [1].

Table 1: Major Splicing Factor Families and Their Functions

| Protein Family | Representative Members | Primary Function | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| SR Proteins | SRSF1, SRSF2, SC35, ASF/SF2 | Splicing activation | Bind ESEs/ISEs; recruit spliceosomal components via RS domains; facilitate exon definition |

| hnRNPs | hnRNP A1/A2, hnRNP H, hnRNP F, hnRNP M | Splicing repression | Bind ESSs/ISSs; compete with SR proteins; sterically block splice site recognition |

| Tissue-Specific Regulators | nPTB, NOVA1/2, CELF1-6, RBM35a/b | Context-dependent regulation | Modulate splicing in tissue-specific manner; respond to developmental cues |

Types and Patterns of Alternative Splicing

Systematic analyses of ESTs and microarray data have identified seven main types of alternative splicing, each with distinct characteristics and prevalence across species [3]. The most common patterns include:

- Cassette exon (Exon skipping): The most prevalent pattern (~30%) in vertebrates and invertebrates, where an exon is either included or skipped in the mature mRNA [3]

- Alternative 5' splice site: Selection of different 5' splice sites within an exon, accounting for approximately 25% of alternative splicing events [1] [3]

- Alternative 3' splice site: Selection of different 3' splice sites within an exon, representing approximately 25% of events [1] [3]

- Mutually exclusive exons: Selection of one exon from a pair or set of possible exons [1]

- Intron retention: The most common pattern in lower metazoans, where an intron is retained in the mature transcript. In human transcripts, intron retention is positioned primarily in untranslated regions (UTRs) and has been associated with weaker splice sites, short intron length, and regulation of cis-regulatory elements [3]

- Alternative promoter: Utilization of different transcription start sites [1]

- Alternative polyadenylation: Selection of different polyadenylation sites, which influences coding potential or 3'UTR length by modifying microRNA or protein binding availability [1] [3]

Table 2: Types of Alternative Splicing and Their Characteristics

| Splicing Type | Description | Prevalence in Humans | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon Skipping (Cassette) | Entire exon is included or skipped | ~30% (Most common) | Can dramatically alter protein structure and function |

| Alternative 5'SS | Different donor splice sites selected | ~25% | Subtle changes at protein N-terminus |

| Alternative 3'SS | Different acceptor splice sites selected | ~25% | Subtle changes at protein C-terminus |

| Mutually Exclusive Exons | One exon selected from a cluster | Variable | Significant domain alterations |

| Intron Retention | Intron remains in mature transcript | ~1-5% (Higher in UTRs) | Can introduce PTCs or alter UTR regulation |

| Alternative Promoters | Different transcription start sites | Not quantified | Affects N-terminal protein sequence |

| Alternative Polyadenylation | Different cleavage/polyA sites | Widespread | Affects 3'UTR length and regulatory elements |

A notable example of alternative splicing complexity is the human gene TTN, which encodes the muscle protein titin and contains 364 coding exons with 4,039 different splicing events identified by RNA-sequencing [1]. Most human genes generate at least two transcript variants, with the alternative spliced mRNAs translated into protein variants that differ in function and structure [1].

Experimental Methods and Analysis

Single-Molecule Splicing Visualization

Advanced methodologies now enable the study of splicing of isolated single pre-mRNA molecules in real time, providing unprecedented resolution of spliceosome dynamics [4]. In this system, a fluorescently tagged pre-mRNA is tethered to a glass surface via its 3'-end. Splicing can be observed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae whole cell extract by monitoring loss of intron-specific fluorescence with a multi-wavelength total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope [4].

Key Technical Considerations:

- Fluorophore Selection: Rhodamines, Cy dyes, and Alexa dyes with high quantum yields are necessary due to substantial autofluorescence of cell extracts

- Oxygen Scavenging: Enzymatic systems using protocatechuate dioxygenase (PCD) or galactose oxidase extend fluorophore lifetimes >100-fold without inhibiting splicing, unlike traditional glucose oxidase systems that deplete ATP [4]

- Two-Color Colocalization: Pre-mRNA molecules tagged with fluorescent dyes of different colors in the intron and exon enable detection of splicing as conversion from dual-color to exon-only fluorescence [4]

Experimental Workflow:

- Substrate Preparation: 3'-biotinylated pre-mRNA covalently tagged with Alexa647 in the 3'-exon

- Surface Immobilization: Attachment to PEG-biotin-derivatized glass surface via streptavidin

- Intron Labeling: Hybridization with fluorescent 2'-O-Me/locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligo complementary to intron sequence

- Splicing Reaction: Addition of whole cell extract and splicing components

- Real-Time Imaging: TIRF microscopy to monitor fluorescence changes during splicing

- Data Analysis: Quantification of splicing kinetics through fluorescence signal loss from intron tag [4]

Splicing Quantitative Trait Loci (sQTL) Analysis

sQTL mapping identifies genetic variants that influence splicing patterns, providing functional insights into disease-associated variants from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [5] [6]. Advanced statistical methods have been developed to analyze sQTLs using RNA-Seq data:

Exon-Inclusion Level Estimation: The proportion of mRNAs originating from the exon-inclusion isoform is estimated using algorithms like PennSeq, which considers all mapped reads in an exon-trio (alternative exon plus flanking constitutive exons) [6]. Unlike methods that only use junction reads, PennSeq utilizes reads aligning to the alternative exon body and flanking constitutive exons, accounting for non-uniform read distribution and paired-end information [6].

Statistical Methods for sQTL Detection:

- Random Effects Meta-Regression: Currently the most reliable and powerful method, accounting for both within-study variation (variance in exon-inclusion level estimation) and between-study variation (variation in exon-inclusion levels across samples) [6]

- Beta Regression: Models exon-inclusion level directly as a beta-distributed variable, producing readily interpretable results without logit transformation [6]

- Generalized Linear Mixed Effects Model (GLiMMPS): An earlier approach that accounts for variation in exon-specific read coverage and overdispersion of read counts but has limitations in handling non-uniform read distribution [6]

The random effects meta-regression approach demonstrates lower false discovery rates and higher power compared to other methods, making it particularly valuable for identifying sQTLs with functional significance in complex diseases [6]. Application of these improved methods has implicated specific variants in neurodegenerative diseases, such as rs528823 in Alzheimer's disease, where antisense oligonucleotides blocking the implicated YBX3 binding site lead to exon skipping in MS4A3 [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Splicing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Splicing Systems | HeLa Nuclear Extract, S. cerevisiae Whole Cell Extract | Provide splicing machinery for biochemical assays | Yeast extract allows genetic manipulation; HeLa extract for mammalian contexts |

| Fluorescent Dyes | Alexa488, Alexa555, Alexa647, Cy Dyes | Single-molecule visualization; FRET studies | High quantum yields needed for extract autofluorescence; PCD system extends lifetime |

| Oxygen Scavengers | Protocatechuate Dioxygenase (PCD), Galactose Oxidase | Prolong fluorophore lifetime in single-molecule assays | Preferred over glucose oxidase in yeast extract to prevent ATP depletion |

| Specialized Oligos | 2'-O-Me/LNA Chimeras, Biotinylated RNAs | Detection, immobilization, and manipulation | LNA increases specificity and reduces dissociation rates |

| sQTL Analysis Tools | PennSeq, MAJIQTL, GLiMMPS | Quantify isoform expression; identify genetic regulators | PennSeq accounts for non-uniform read distribution; MAJIQTL improves sGene discovery |

| Splicing Modulators | Small molecule inhibitors, Antisense Oligonucleotides | Mechanistic studies; therapeutic development | Target conserved active site of splicing machines; induce specific exon skipping |

Tissue Specificity and Physiological Regulation

The distribution of alternative splicing factors exhibits remarkable tissue specificity, contributing to cellular differentiation and functional diversity across tissues [1]. More than 50% of genes express different alternative spliced isoforms among tissues, with specialized splicing programs particularly evident in the nervous system, muscle tissues, and epithelial cells [1].

Neural Tissue: The human brain, the most functionally diverse tissue, contains several specific splicing factors including nPTB, NOVA1, and NOVA2 [1]. During neuronal differentiation, the expression of splicing factors shifts from PTB to nPTB, with PTB upregulation responsible for approximately a quarter of nervous system-specific alternative splicing [1]. The CELF family proteins (CELF1, CELF2, CELF5, CELF6) are broadly expressed in the brain, serving as alternative splicing regulators that primarily target gene TNTT2, with CELF2 and CELF5 also distributed in heart and skeletal muscle tissues [1].

Epithelial Tissue: RBM35a and RBM35b function as epithelial cell-specific splicing factors, controlling the expression of epithelial characteristics-related exons [1]. This tissue-specific regulation enables the generation of protein isoforms tailored to the specialized functions of different cell types.

The regulation of alternative splicing extends to coupling with transcription processes, where physical and functional connections between mRNA splicing, RNA polymerase II, and chromatin structure create coordinated regulatory mechanisms [3]. The carboxyl terminal domain (CTD) of the large subunit of RNAPII, consisting of 52 tandem repeats of the heptapeptide YSPTSPS in mammals, serves as a platform to recruit different factors to nascent transcripts via dynamic phosphorylation of serine residues [3]. This coupling mechanism ensures efficient and coordinated gene expression, with splicing factors recruited to transcription sites influencing both splicing outcomes and transcriptional elongation.

Pathological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Splicing Dysregulation in Disease

Aberrations in splicing regulation represent a fundamental mechanism in numerous diseases, particularly cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [1] [2]. Mutations in splicing factor genes or dysregulation of their expression can disrupt the network of downstream splicing targets, leading to pathological consequences [1].

Cancer Pathogenesis: Alternative splicing plays a key role in post-transcriptional regulation and controls the formation of spliced variants, with mutations and altered levels of splice factors contributing to tumorigenesis [1]. Abnormal expressions of specific splicing isoforms impact cellular activities central to cancer progression, including sustaining proliferation, preventing cell death, rewiring cell metabolism, promoting angiogenesis, enabling invasion and metastatic dissemination, and conferring drug resistance [1].

Key splicing factors implicated in oncogenesis include:

- SF3B1: Mutations highly associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), cutaneous melanomas, and uveal melanomas. Mutated SF3B1 disturbs interaction with SF3B14a, preventing proper branch point recognition and causing 3'-splice site mis-selection [1]

- SRSF1: Frequently upregulated in breast tumors through binding with MYC, increasing cell proliferation and decreasing apoptosis. SRSF1 overexpression in lung cancer leads to resistance to chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and topotecan [1]

- SRSF2: Mutations associated with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), where altered binding specificity induces inclusion of premature termination codons in EZH2, encoding a histone methyltransferase related to MDS pathogenesis [1]

- hnRNP A1/A2: Upregulated in lung cancer and functions as a carcinogenic factor to promote cell proliferation. These proteins also participate in recognizing and protecting telomeric sequences, linking them to cancer regulation [1]

Neurodegenerative Disorders: Splicing abnormalities are increasingly recognized as contributors to neurodegenerative diseases. Advanced sQTL analysis methods have identified specific variants like rs528823 in Alzheimer's disease, affecting splicing regulation through disruption of transcription factor binding sites [5]. Similarly, splicing dysregulation features in Parkinson's disease and other neurological conditions, often through altered expression of neural-specific splicing factors like NOVA and nPTB [1] [5].

Therapeutic Interventions Targeting Splicing

The modulation of RNA splicing by small molecules has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for treating pathogenic infections, human genetic diseases, and cancer [7]. Recent structural studies have visualized splicing modulation at near-atomic resolution, enabling structure-based drug design approaches [7].

Small Molecule Modulators: Integrating enzymatic, crystallographic, and simulation studies has demonstrated that self-splicing group II introns recognize small molecules through their conserved active site [7]. These RNA-binding small molecules selectively inhibit splicing steps by adopting distinctive poses at different catalytic stages and preventing crucial active site conformational changes essential for splicing progression [7]. This work provides a solid basis for rational design of splicing modulators targeting not only bacterial and organellar introns but also the human spliceosome, a validated drug target for congenital diseases and cancers [7].

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): ASOs designed to block specific splicing regulatory elements can redirect splicing outcomes. For example, antisense oligonucleotides targeting the YBX3 binding site affected by Alzheimer's-associated variant rs528823 induce exon skipping in MS4A3, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of splicing modulation [5].

Novel Chemical Compounds: Patent applications have been filed covering novel chemical compounds acting as splicing modulators, with future development aimed at regulating production of specific proteins linked to defective or mutated genes [7]. These advances hold promise for developing new antibacterials and antitumor agents that directly target genetic mutations altering gene expression processes [7].

The comprehensive understanding of RNA splicing mechanisms, from constitutive splicing to alternative isoform generation, provides critical insights into gene regulation and protein diversity. The intricate coordination of spliceosome assembly, cis-regulatory elements, trans-acting factors, and tissue-specific regulators enables precise control of gene expression outcomes. Experimental advances, particularly in single-molecule visualization and sQTL mapping, continue to reveal the complexity of splicing regulation and its functional consequences.

The pathological significance of splicing dysregulation underscores the importance of this process in human health and disease. As structural insights into splicing mechanisms improve and therapeutic targeting strategies advance, the potential for developing novel treatments for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and genetic disorders through splicing modulation continues to expand. The integration of biochemical, genetic, computational, and structural approaches will further elucidate the fundamental principles of splicing regulation and its applications in precision medicine.

Alternative splicing (AS) is a fundamental mechanism in eukaryotic gene regulation that enables a single gene to produce multiple mRNA isoforms, thereby vastly expanding proteomic diversity from a finite genome [3]. This process is critical for cellular differentiation, organismal development, and response to environmental stimuli, and its misregulation is implicated in numerous human diseases [3] [8]. While constitutive splicing involves the removal of introns and ligation of exons in a fixed order, alternative splicing creates variation by differentially selecting splice sites. This review focuses on three major types of alternative splicing—exon skipping, intron retention, and alternative splice site selection—framed within the context of their contributions to protein diversity mechanisms. We provide a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, complete with quantitative comparisons, experimental methodologies, and visualization of underlying mechanisms.

Classification and Prevalence of Major Alternative Splicing Types

Systematic analyses have revealed several major types of alternative splicing events. The most prevalent pattern in vertebrates and invertebrates is cassette-type alternative exon (exon skipping), accounting for approximately 30% of alternative splicing events in these organisms [3]. In contrast, intron retention is the most frequent alternative splicing event in plants and is also common, though scientifically neglected, in animals [9] [3]. Alternative 5' or 3' splice site selection, which involves subtle changes in exon boundaries, constitutes approximately 25% of alternative splicing events [3]. The prevalence of different splicing types varies significantly across biological kingdoms, with intron retention being particularly prominent in lower metazoans [3].

Table 1: Major Types of Alternative Splicing and Their Characteristics

| Splicing Type | Prevalence in Vertebrates | Key Features | Impact on Coding Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon Skipping | ~30% [3] | Complete exclusion of an exon from mature transcript | Can cause large deletions of protein domains |

| Intron Retention | Most common in plants; frequent in animals [9] | Retention of entire intron in mature mRNA | Often introduces PTCs leading to NMD or truncated proteins |

| Alternative 5' Splice Site | ~25% (combined) [3] | Alternative donor site selection within same exon | Subtle changes at protein N-terminus |

| Alternative 3' Splice Site | ~25% (combined) [3] | Alternative acceptor site selection within same exon | Subtle changes at protein C-terminus |

| Mutually Exclusive Exons | Less common | Selection of one exon from a set of possibilities | Domain swapping in resulting protein |

Molecular Mechanisms and Regulatory Principles

Fundamental Splicing Machinery

The splicing process is executed by a massive ribonucleoprotein complex called the spliceosome, which consists of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs: U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) and numerous associated protein factors [3]. Splicing requires two consecutive transesterification reactions: first, a nucleophilic attack of the branch point adenosine on the 5' splice site, forming a lariat intermediate; second, the 3' OH of the upstream exon attacks the 3' splice site, resulting in exon ligation and intron release [9]. The spliceosome recognizes core splicing signals: the 5' splice site (5'ss), branch point sequence (BPS), polypyrimidine tract (PPT), and 3' splice site (3'ss) [3] [10].

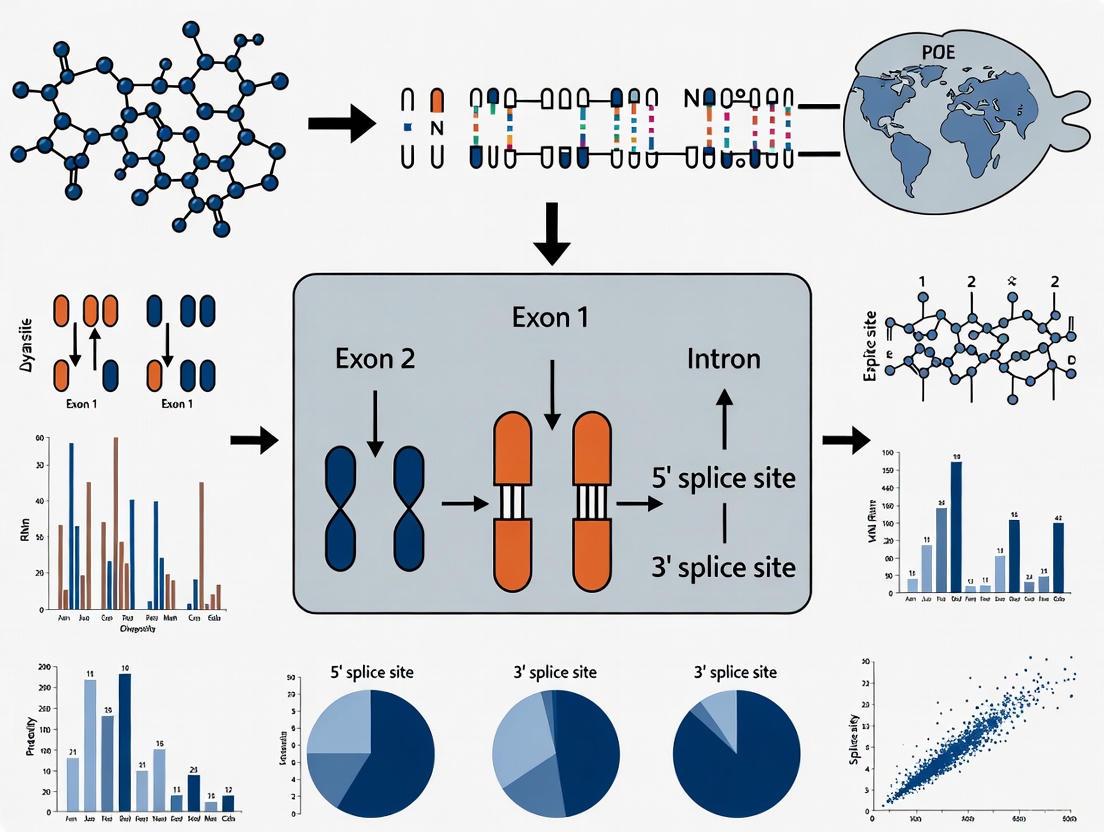

Diagram 1: Pre-mRNA Splicing Mechanism

cis-Acting Elements and trans-Acting Factors

Alternative splicing decisions are governed by the interplay between cis-regulatory elements and trans-acting factors. Cis-acting elements include exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs), intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs), exonic splicing silencers (ESSs), and intronic splicing silencers (ISSs) [3]. These elements are recognized by trans-acting factors: SR proteins (serine/arginine-rich proteins) typically bind enhancers and promote splicing, while heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) often bind silencers and inhibit splicing [3]. The combinatorial action of these regulatory components determines the splicing outcome, with silencers playing a particularly important role in alternative splicing control [3].

Splice Site Selection Principles

Splice site selection follows specific principles influenced by genomic architecture. The "proximity rule" states that when multiple splice sites compete, the spliceosome preferentially pairs sites that are closest to each other [10]. However, this rule operates differently depending on intron-exon architecture. For short introns (<250 nucleotides), the intron definition mode predominates, favoring pairing of the 5' and 3' splice sites closest across the intron [10]. For exons flanked by long introns (>250 nucleotides), exon definition operates, favoring pairing of the 5' and 3' splice sites closest across the exon [10].

Table 2: Genomic Architecture Influences on Splice Site Selection

| Architectural Context | Definition Mode | Proximity Principle | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Flanking Introns (<250 nt) | Intron Definition | Splice sites closest across the intron are paired [10] | Common in lower eukaryotes [10] |

| Long Flanking Introns (>250 nt) | Exon Definition | Splice sites closest across the exon are paired [10] | Common in humans (>87% of introns) [10] |

| Hybrid Architecture (one short, one long intron) | Context-Dependent | Intermediate behavior with bias toward intron or exon definition [10] | Less common |

Exon Skipping

Mechanism and Functional Consequences

Exon skipping, also known as cassette exon splicing, involves the complete exclusion of an exon from the mature mRNA transcript [3]. This is the most prevalent alternative splicing type in vertebrates and invertebrates [3]. The mechanism involves the splicing machinery skipping over an exon and joining the upstream and downstream exons directly. This results in an mRNA missing the coding information of the skipped exon, which can lead to deletion of entire protein domains or disruption of the reading frame [11].

From a protein diversity perspective, exon skipping represents a powerful mechanism for generating functionally distinct protein isoforms. When the reading frame is preserved, exon skipping can produce proteins with altered functional properties, including modified binding characteristics, subcellular localization, enzymatic activity, or protein-protein interaction domains [3].

Therapeutic Application: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Exon skipping has been successfully leveraged as a therapeutic strategy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a severe genetic disorder caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene that disrupt the reading frame [11]. The approach uses antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) that bind to specific exons in the pre-mRNA and induce skipping of the mutated exon, thereby restoring the reading frame and converting the lethal DMD phenotype to the milder Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) phenotype [11].

Diagram 2: Exon Skipping Therapeutic Mechanism for DMD

Several exon-skipping drugs have received FDA approval: eteplirsen (Exondys 51) targets exon 51, golodirsen (Vyondys 53) and viltolarsen (Viltepso) target exon 53, and casimersen targets exon 45 [11]. Since DMD mutations cluster in "hot spot" regions (primarily exons 45-53), skipping these exons could potentially treat up to 50% of DMD patients [11].

Intron Retention

Mechanism and Functional Consequences

Intron retention (IR) occurs when an intron remains in the mature mRNA transcript instead of being spliced out [8]. This was historically considered a splicing error but is now recognized as a functionally important regulatory mechanism [9] [8]. IR is the most prevalent alternative splicing type in plants and is increasingly recognized as significant in mammalian systems [9].

Retained introns often contain premature termination codons (PTCs), making the transcripts targets for nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), thus providing a mechanism for post-transcriptional gene regulation [8]. In some cases, intron-retaining transcripts (IRIs) are detained in the nucleus and can undergo further splicing in response to specific signals or cellular states [9] [8]. Alternatively, IRIs may escape NMD and be translated into protein isoforms that are often truncated and may lack functional domains or, in some cases, contain extra domains encoded by the retained intronic sequence [8].

Biological Functions and Regulatory Roles

Intron retention serves as an important regulatory mechanism in various biological processes. During neuronal differentiation, increased IR contributes to gene expression downregulation by targeting transcripts to NMD [8]. In activated CD4+ T cells, upregulation of most genes is accompanied by significantly decreased IR levels, suggesting a rapid response mechanism to extracellular stimuli [8]. IR also plays roles in erythropoiesis, where dynamic increases in IR occur during late erythroblast differentiation [8].

Recent studies have identified intron retention quantitative trait loci (irQTLs) in human tissues, with 8,624 unique IR events associated with genetic polymorphisms [12]. Notably, 16% of these irQTLs are associated with genome-wide association study (GWAS) traits, highlighting the clinical relevance of IR [12].

Alternative Splice Site Selection

Mechanism and Functional Consequences

Alternative splice site selection involves the use of different 5' or 3' splice sites within the same exon, leading to subtle changes in exon boundaries [3]. This results in extended or shortened exons in the mature mRNA. Alternative 5' splice site selection changes the upstream boundary of an exon, while alternative 3' splice site selection alters the downstream boundary [3].

The functional impact of alternative splice site selection is typically more subtle than exon skipping but can still significantly affect protein function. These changes may alter the coding sequence by adding or removing a small number of amino acids, potentially affecting protein interaction interfaces, catalytic sites, or post-translational modification sites [3]. In some cases, alternative splice site selection can introduce frameshifts with more dramatic consequences.

Determinants of Splice Site Strength

Splice site selection is heavily influenced by splice site strength, which is determined by how well the sequence conforms to consensus motifs and its ability to recruit splicing factors [13] [14]. The 5' splice site consensus in mammals is MAG|GURAGU (where | indicates the exon-intron boundary and M = A/C, R = purine) [14], while the 3' splice site consists of the branch point sequence, polypyrimidine tract, and YAG| (where Y = pyrimidine) [10].

Recent approaches have focused on empirically quantifying splice site usage/strength rather than relying solely on predictive algorithms. The SpliSER (Splice-site Strength Estimate from RNA-seq) tool quantifies empirical usage of individual splice sites from RNA-seq data, providing a direct measurement of splice site strength [13] [14]. This approach has revealed that sequence variation in cis rather than trans is primarily associated with splicing variation among natural accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana [13].

Experimental Methods for Detection and Quantification

Computational Detection Methods

Various computational methods have been developed to detect and quantify alternative splicing events from RNA-seq data:

GESS (graph-based exon-skipping scanner): A de novo method for detecting exon-skipping events from raw RNA-seq reads without prior knowledge of gene annotations [15]. It builds a splice-site-link graph from RNA-seq reads and identifies sub-graphs with patterns corresponding to exon-skipping events.

SpliSER (Splice-site Strength Estimate from RNA-seq): Quantifies empirical usage of individual splice sites, defined as SSE = α / (α + β1 + β2), where α represents reads supporting site usage, and β1 and β2 represent reads indicating non-usage [13].

IRFinder and iREAD: Tools specifically designed for intron retention detection that quantify IR levels by assessing reads aligning to intronic regions compared to exonic regions [8].

MISO (Mixture of Isoforms): A probabilistic framework that quantifies the expression of alternatively spliced isoforms from RNA-seq data [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Alternative Splicing Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Key Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (AONs) | Therapeutic exon skipping; experimental splicing modulation | Short nucleic acid polymers (typically ≤50 bases) that bind target sequences to modulate splicing | [11] |

| SpliSER | Quantifying empirical splice site usage | Provides Splice-site Strength Estimate (SSE) from RNA-seq data; enables GWAS of splicing variation | [13] [14] |

| GESS | De novo exon-skipping detection | Identifies skipping events without annotation bias; uses splice-site-link graphs | [15] |

| IRFinder | Intron retention quantification | Specifically optimized for IR detection; accounts for mapping biases | [8] |

| MISO | Isoform quantification | Bayesian framework for estimating isoform ratios; incorporates uncertainty | [15] |

The major types of alternative splicing—exon skipping, intron retention, and alternative splice site selection—represent powerful mechanisms for generating proteomic diversity and regulating gene expression. Each mechanism possesses distinct characteristics, prevalence across species, and functional consequences. Exon skipping enables domain-level changes in proteins and has proven clinically actionable for DMD treatment. Intron retention serves as an important regulatory mechanism, particularly in differentiation and stress response. Alternative splice site selection provides fine-scale modulation of protein features. Ongoing technological advances in empirical splice site quantification and detection methods continue to enhance our understanding of the splicing code and its contributions to phenotypic diversity and disease pathogenesis.

Alternative splicing is a fundamental post-transcriptional process that enables a single gene to generate multiple mRNA and protein isoforms, dramatically expanding the functional complexity of the genome and proteome [16] [17]. Over 90% of human multi-exonic genes undergo alternative splicing, producing distinct proteoforms with varied functions, localization, and interaction partners [16] [18]. This process is critically regulated by cis-acting regulatory elements—short, non-coding RNA sequences that serve as binding platforms for trans-acting splicing factors [16] [17]. These elements fine-tune splice site selection and exon inclusion rates, forming a sophisticated "splicing code" that determines transcriptional outcomes [19]. Disruption of this delicate balance can lead to aberrant splicing associated with numerous human diseases, including cancer, neurological disorders, and channelopathies [20] [17]. Understanding the mechanisms and locations of these regulatory elements is therefore essential for both basic research and therapeutic development.

Classification and Mechanisms of cis-Acting Splicing Elements

Cis-acting splicing elements are traditionally classified based on their location and function into four main categories. These elements work combinatorially to define exon boundaries and regulate alternative splicing patterns.

Table 1: Classification of cis-Acting Splicing Regulatory Elements

| Element Type | Location | Function | Key Binding Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exonic Splicing Enhancer (ESE) | Exon | Promotes exon inclusion | SR proteins (e.g., SRSF1) [17] |

| Exonic Splicing Silencer (ESS) | Exon | Promotes exon skipping | hnRNPs (e.g., hnRNP A1) [17] [19] |

| Intronic Splicing Enhancer (ISE) | Intron | Promotes exon inclusion | SR proteins, other activators [17] |

| Intronic Splicing Silencer (ISS) | Intron | Promotes exon skipping | hnRNPs, other repressors [17] |

The precise spatial organization of these elements creates a regulatory landscape that guides the spliceosome. The core spliceosome machinery, consisting of U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNPs, recognizes canonical splice sites but requires additional regulation for accurate splicing decisions [16] [17]. Splicing enhancers facilitate exon definition by promoting the recruitment and stability of spliceosomal components, particularly U1 and U2 snRNPs, at flanking splice sites [16]. Silencers, in contrast, act antagonistically by blocking the access of core splicing factors or recruiting inhibitory complexes [17]. The functional outcome for a given exon depends on the dynamic interplay between these antagonistic forces.

Table 2: Characteristics of Core Splicing Motifs and Regulatory Elements

| Feature | Core Splicing Motifs | Splicing Regulatory Elements (ESEs, ESSs, etc.) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Define exon-intron boundaries (5'SS, 3'SS, BPS, PPT) [21] | Modulate the strength of core motifs and fine-tune exon inclusion [17] |

| Sequence Conservation | Highly conserved GU-AG rule at intron boundaries [16] | Less conserved, degenerate sequences [19] |

| Typical Length | Short, defined motifs (e.g., 5'SS: 9 nt; BPS: 7 nt) [21] | Short, degenerate sequences (6-8 nt) [19] |

| Effect of Mutation | Often complete loss of splicing at the affected site [16] | Subtle to strong modulation of exon inclusion levels [19] |

The following diagram illustrates the spatial relationships and functional impacts of these cis-regulatory elements within a prototypical exon-intron unit:

Diagram 1: Spatial organization and function of cis-acting splicing elements. Enhancers (green) and silencers (red) within exons and introns bind trans-acting factors to either promote or inhibit splice site recognition.

Quantitative Analysis of Splicing Regulatory Landscapes

Large-scale genomic studies have systematically defined the sequence and spacing requirements for effective splicing. Analysis of approximately 202,000 canonical protein-coding exons revealed that 95.9% adhere to defined minimal splicing criteria encompassing specific sequence motifs, strength thresholds, and spatial organization [21]. The branch point sequence (BPS), a critical cis-element, is typically located 18-48 nucleotides upstream of the 3' splice site, with the adenosine branch point itself positioned 21-34 nucleotides from the 3'SS [21].

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters of Core Splicing Motifs from Genome-Wide Analysis

| Splicing Motif | Consensus Sequence | Typical Location | Strength Metric (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5' Splice Site (5'SS) | AGGTRAGT | Exon-Intron Junction | MaxEntScan Score: 4.0 - 11.9 [21] |

| 3' Splice Site (3'SS) | YAG | Intron-Exon Junction | MaxEntScan Score: 3.5 - 13.2 [21] |

| Branch Point (BP) | YURAY | 18-48 nt upstream of 3'SS [21] | Distance from 3'SS: 21-34 nt (A branch) [21] |

| Polypyrimidine Tract (PPT) | Pyrimidine-rich (C/T) | Between BP and 3'SS | Length: Highly variable |

Not all exons are equally dependent on regulatory elements. The concept of "exon vulnerability" has emerged from studies showing that certain exons, such as ACADM exon 5, are highly sensitive to exonic mutations because they inherently lack strong splicing enhancers or possess potent silencers [19]. These vulnerable exons exist in a precarious balance, where even single nucleotide variations can disrupt the equilibrium between enhancer and silencer elements, leading to aberrant splicing and disease [19]. Computational tools like VulExMap have been developed specifically to identify such constitutive exons that are vulnerable to exonic splice mutations [19].

Experimental Methodologies for Mapping and Validation

Genome-Wide Epigenomic Profiling

Comprehensive identification of regulatory elements in complex genomes requires integrated epigenomic approaches. A multi-assay strategy can map active regulatory regions, including promoters and enhancers that may influence splicing patterns.

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq): Identifies genomically accessible, open chromatin regions, a key feature of active regulatory elements [22].

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing (ChIP-seq): Maps histone modifications associated with active enhancers (H3K27ac, H3K4me1) and promoters (H3K4me3) [22].

- Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): Provides single-nucleotide resolution DNA methylation maps. Active regulatory elements often exhibit hypomethylation, particularly in CG and CHG contexts [22].

- RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq): Measures transcriptome-wide gene expression and alternative splicing patterns, allowing correlation of regulatory element activity with transcriptional outcomes [22].

Integrated analysis of these datasets enables the discrimination of different classes of regulatory elements based on their combinatorial chromatin signatures. Active promoters are typically marked by open chromatin, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac, while enhancers are primarily characterized by open chromatin with variable H3K27ac and H3K4me1 levels [22].

Functional Validation of Splicing Elements

Once candidate regulatory elements are identified, their functional validation is essential. The following workflow outlines a standard pipeline for experimental characterization:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for validating cis-acting splicing elements, incorporating computational prediction and database interrogation.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Minigene Splicing Assay

The minigene assay is a gold-standard method for functionally testing putative splicing regulatory elements without endogenous genomic context confounding effects.

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Splicing Analysis Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| SpliceVec Minigene Vector | Backbone for inserting genomic fragments of interest | Contains multiple cloning sites, constitutive exons, and viral promoter (e.g., CMV) [21] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduction of specific variants into minigene constructs | Enables testing of wild-type vs. mutant regulatory elements [21] |

| Cell Line (HEK293T, HeLa) | Heterologous system for splicing analysis | High transfection efficiency, well-characterized splicing patterns [21] |

| RT-PCR Kit | Analysis of splicing patterns from expressed minigenes | Detects alternative isoforms; use of fluorescent primers enables quantitative analysis [21] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | High-resolution separation of splicing isoforms | Provides quantitative data on exon inclusion/skipping ratios [21] |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Minigene Construct Design: Clone the genomic region of interest (typically containing an exon with flanking intronic sequences) into a splicing reporter vector between two constitutive exons. The insert size is generally 500-1500 bp [21].

Variant Introduction: Use site-directed mutagenesis to introduce specific mutations into candidate regulatory elements (ESEs, ESSs, etc.) within the cloned fragment. Include positive and negative control constructs.

Cell Transfection: Transfect the minigene constructs into mammalian cells using a standardized method (e.g., lipofection). Perform triplicate transfections and include an empty vector control.

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis: Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-transfection. Isolate total RNA using a column-based method, treating with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination. Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT) or random hexamer primers.

PCR Amplification: Amplify the minigene transcript using PCR with primers binding to the vector's constitutive exons. Use a fluorescently labeled primer for quantitative analysis. Limit PCR cycles to remain in the exponential amplification phase (typically 25-30 cycles).

Splicing Product Analysis: Separate and quantify PCR products by capillary electrophoresis. Calculate the Percent Spliced In (PSI or Ψ) for the exon of interest using the formula: Ψ = (Inclusion peak height / (Inclusion peak height + Skipping peak height)) × 100. Compare Ψ values between wild-type and mutant constructs to determine the functional impact of the mutated regulatory element.

Sequence Verification: Sanger sequence the PCR products to confirm the identity of each splicing isoform.

Computational Tools and Databases for Splicing Element Analysis

Advancements in computational biology have produced sophisticated tools for predicting the impact of sequence variations on splicing regulation. These resources are invaluable for prioritizing variants for functional studies.

SpliceVarDB: A comprehensive database consolidating over 50,000 experimentally validated variants assayed for their effects on splicing across more than 8,000 human genes [23]. Approximately 25% are classified as "splice-altering," with 55% of these located outside canonical splice sites, providing crucial data for interpreting variants of uncertain significance [23].

DeepCLIP: A deep learning-based tool that predicts the binding of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) to RNA sequences, and how mutations affect this binding [19]. This is particularly valuable for understanding how sequence variations in regulatory elements disrupt protein-RNA interactions critical for splicing regulation.

VulExMap: A computational method specifically designed to identify constitutive exons that are vulnerable to exonic splice mutations [19]. This helps prioritize exons where exonic mutations are most likely to cause splicing defects.

PTM-POSE: An open-source Python tool that projects post-translational modification (PTM) sites onto splice events, enabling systematic analysis of how alternative splicing may alter the PTM landscape of protein isoforms [18]. This is relevant for understanding the functional consequences of splicing regulation on protein function.

These tools, combined with established splice prediction algorithms like SpliceAI and Pangolin, provide researchers with a powerful toolkit for in silico assessment of splicing regulatory elements [21].

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The modulation of splicing through cis-regulatory elements represents a promising therapeutic avenue for genetic diseases and cancer. Splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are synthetic molecules designed to bind specific RNA sequences and block the access of trans-acting factors to cis-regulatory elements, thereby altering splicing patterns [16] [17]. For example, ASOs can be targeted to ISS elements to promote exon inclusion or to ESEs to block enhancer function and induce exon skipping [16]. This approach has achieved clinical success in treating neuromuscular disorders like Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy [16].

Furthermore, the discovery of poison exons—exons whose inclusion introduces a premature termination codon leading to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the transcript—offers another therapeutic strategy [24]. Small molecules or ASOs can be designed to modulate the splicing of these PEs, thereby tuning the expression of specific genes [24]. This is particularly promising for targeting genes traditionally considered "undruggable."

In cancer, aberrant splicing is a hallmark, with tumors exhibiting up to 30% more alternative splicing events than normal tissues [17]. Mutations in splicing factors (e.g., SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1) and dysregulation of SR proteins and hnRNPs are common oncogenic drivers [17]. Small molecule inhibitors targeting the spliceosome (e.g., sudemycins, pladienolide B) and ASOs designed against cancer-specific isoforms are under active investigation as anticancer therapeutics [17]. The ongoing development of these targeted interventions underscores the critical importance of understanding cis-acting regulatory elements for advancing precision medicine.

Alternative splicing represents a pivotal regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic gene expression, dramatically expanding the functional and regulatory complexity of the proteome. This process is orchestrated by intricate interactions between cis-acting regulatory elements within pre-mRNA and trans-acting splicing factors, primarily comprising serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs). These two major families of RNA-binding proteins function antagonistically and cooperatively to define splice site selection, regulate alternative splicing outcomes, and influence downstream mRNA metabolism. SR proteins generally promote exon inclusion through binding to exonic splicing enhancers, while hnRNPs often facilitate exon exclusion by recognizing exonic or intronic splicing silencers. Understanding the precise mechanisms, structural features, and functional relationships between these regulators provides critical insights into normal development, tissue-specific differentiation, and disease pathogenesis, particularly in neurological disorders and cancer. This technical guide comprehensively examines the molecular architecture, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental approaches for investigating SR proteins and hnRNPs, serving as an essential resource for researchers exploring splicing mechanisms and their therapeutic applications.

Alternative splicing enables a single gene to generate multiple mRNA isoforms through differential inclusion of exonic and intronic sequences, contributing significantly to proteomic diversity. More than 95% of human multi-exon genes undergo alternative splicing, with the highest complexity observed in neural tissues [2] [25]. This process is governed by the coordinated action of cis-regulatory elements and trans-acting factors that collectively determine splice site recognition and usage [3].

The two principal classes of trans-acting splicing factors—SR proteins and hnRNPs—operate within an integrated network that responds to cellular signals, environmental cues, and developmental programs. SR proteins, characterized by RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and arginine/serine-rich (RS) domains, typically function as splicing activators [26]. In contrast, hnRNPs, containing varied RNA-binding domains such as RRMs, quasi-RRMs (qRRMs), KH domains, and RGG boxes, often serve as splicing repressors [27] [25]. The balance between these antagonistic forces fine-tunes splicing outcomes in a context-dependent manner, with disruptions leading to numerous human diseases [2].

Beyond their splicing functions, both protein families participate in broader RNA metabolic processes, including mRNA export, stability, translation, and decay. This functional versatility positions SR proteins and hnRNPs as central regulators of gene expression pathways, making them compelling targets for therapeutic intervention in splicing-related disorders [2].

Molecular Structure and Classification

SR Proteins: Domain Architecture and Family Members

SR proteins constitute a conserved family of splicing regulators characterized by a modular structure comprising one or two N-terminal RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and a C-terminal RS domain rich in arginine-serine dipeptides [26]. The RRM domains mediate sequence-specific RNA binding, primarily to exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs), while the RS domain facilitates protein-protein interactions with other splicing components and recruits the basal splicing machinery [28] [26].

Table 1: Major SR Protein Family Members and Characteristics

| Gene | Protein Aliases | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Domains | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRSF1 | ASF/SF2, SRp30a | 28-33 | 2xRRM, RS | Prototypical SR protein; essential for viability; regulates alternative splicing and mRNA export |

| SRSF2 | SC35, SRp30b | ~30 | 1xRRM, RS | Critical for spliceosome assembly; recognizes specific purine-rich ESEs |

| SRSF3 | SRp20 | ~20 | 1xRRM, RS | Shuttling SR protein; involved in mRNA export; regulates alternative polyadenylation |

| SRSF7 | 9G8 | ~30 | 1xRRM, RS, Zn knuckle | Unique zinc knuckle domain; shuttling protein; binds GAC triplet sequences [28] |

| TRA2B | Transformer-2 beta | ~33 | 1xRRM, RS | Regulates specific exons including SMN2 exon 7; binds to GAARE sequences |

The RS domain exists in a largely unstructured state but undergoes regulated phosphorylation that controls SR protein localization, activity, and interactions. Phosphorylation of serine residues in the RS domain promotes nuclear localization and integration with the splicing machinery, while dephosphorylation facilitates nuclear export and participation in translational regulation [26].

hnRNPs: Structural Diversity and Functional Domains

The hnRNP family encompasses approximately 20 canonical members (hnRNP A-U) with diverse domain architectures and molecular weights ranging from 34-120 kDa [27] [25]. Unlike SR proteins, hnRNPs lack a unifying domain structure but typically contain combinations of RRMs, quasi-RRMs (qRRMs), K homology (KH) domains, and RGG boxes that confer RNA-binding specificity [27].

Table 2: Major hnRNP Family Members and Characteristics

| hnRNP | Isoforms | Molecular Weight (kDa) | RNA-Binding Domains | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hnRNP A/B | A0, A1, A2/B1, A3 | 34-40 | 2xRRM, Gly-rich, RGG | Splicing repression; mRNA stability; telomere maintenance |

| hnRNP C | C1, C2 | 41/43 | RRM, Acid-rich | Early spliceosome assembly; uridine-rich RNA binding |

| hnRNP K | AUKS | 55-65 | 3xKH, Other | Integrates transcription and splicing; regulated by multiple PTMs |

| hnRNP U | SAF-A | 120 | Acid-rich, Gly-rich, RGG, Other | Nuclear matrix association; chromatin interactions |

| hnRNP L | 68 | 4xRRM, Gly-rich | Regulates splicing of specific transcripts including vascular endothelial genes |

The modular composition of hnRNPs, with varied arrangements of structured RNA-binding domains and unstructured auxiliary regions, enables recognition of diverse RNA sequences and participation in multiple steps of RNA processing [25]. Post-translational modifications including phosphorylation, methylation, and ubiquitination further expand the functional repertoire of hnRNPs by modulating their RNA-binding affinity, protein-protein interactions, and subcellular localization [27].

Mechanisms of Splicing Regulation

Basic Splicing Machinery and Regulatory Elements

The spliceosome, a dynamic macromolecular complex comprising five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) and numerous associated proteins, catalyzes pre-mRNA splicing through recognition of consensus sequences at exon-intron boundaries: the 5' splice site, 3' splice site, branch point sequence, and polypyrimidine tract [3]. Alternative splicing introduces additional regulatory complexity through cis-acting elements categorized as exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs), intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs), exonic splicing silencers (ESSs), and intronic splicing silencers (ISSs) [2].

SR proteins predominantly bind to ESEs and ISEs through their RRM domains, then recruit and stabilize core splicing components (U1 snRNP at 5' splice sites and U2AF at 3' splice sites) via phosphorylated RS domains [26]. This recruitment promotes spliceosome assembly on adjacent introns, leading to enhanced inclusion of regulated exons [3] [26].

Conversely, hnRNPs typically bind to ESSs or ISSs and repress splicing through several mechanisms: competitive binding with SR proteins for overlapping sites, steric hindrance that blocks access of spliceosomal components, or direct protein-protein interactions that interfere with spliceosome assembly [27] [2]. Some hnRNPs, such as hnRNP A1, can also promote exon skipping by bridging across exons and looping out intervening sequences [3].

Diagram 1: Competitive regulation of alternative splicing by SR proteins and hnRNPs. SR proteins bind exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) and recruit spliceosomal components through RS domain interactions, promoting exon inclusion. hnRNPs bind exonic or intronic splicing silencers (ESSs/ISSs) and repress splicing through steric hindrance or competitive binding, leading to exon exclusion.

Coordination with Transcription and Chromatin Landscape

Splicing occurs predominantly co-transcriptionally, with the carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II serving as a platform for recruiting splicing factors to nascent transcripts [29] [30]. The phosphorylation state of the CTD heptad repeats (YSPTSPS) changes during transcription elongation, creating a "splicing code" that coordinates the recruitment of specific SR proteins and other splicing regulators at appropriate positions along the gene [30].

Chromatin structure further influences splicing outcomes through multiple mechanisms. Nucleosome positioning correlates with exon definition, with exons exhibiting higher nucleosome occupancy than introns [29]. Histone modifications also impact splicing; for example, H3K36me3 marks associated with transcriptional elongation recruit specific splicing regulators through adaptor proteins [29]. These interconnections demonstrate that splicing regulation is integrated within a broader transcriptional machinery rather than operating as an independent process.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Analyzing Splicing Factor Binding Specificity

Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) has been instrumental in defining the RNA-binding preferences of SR proteins and hnRNPs. The experimental workflow involves:

- Library Preparation: Generating a random oligonucleotide library (typically 20-40 nucleotides in length) flanked by constant primer binding sites.

- Binding Reaction: Incubating the RNA library with the purified splicing factor of interest.

- Partitioning: Separating protein-bound RNAs from unbound sequences through nitrocellulose filter binding, immunoprecipitation, or other capture methods.

- Amplification: Reverse transcribing and PCR amplifying the bound RNAs to generate an enriched library for subsequent rounds of selection.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Cloning and sequencing the selected RNAs after 5-15 rounds of selection, followed by motif analysis to identify consensus binding sequences.

Application of this approach revealed that SR protein 9G8 selects RNA sequences containing GAC triplets, while a mutated zinc knuckle variant of 9G8 selects different sequences centered around a (A/U)C(A/U)(A/U)C motif, demonstrating the importance of auxiliary domains in RNA recognition specificity [28]. Similarly, SELEX experiments with SC35 identified pyrimidine or purine-rich motifs as preferred binding sites [28].

Distinguishing cis- and trans-Directed Splicing Events

Long-read RNA Sequencing with Allelic Linkage Analysis enables systematic identification of splicing events primarily regulated by cis-acting genetic variants versus those controlled by trans-acting factors [31]. The isoLASER method provides a comprehensive workflow:

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Generating full-length cDNA libraries suitable for PacBio or Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing platforms.

- Variant Calling: Identifying heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) directly from RNA-seq data using local reassembly approaches and machine learning classifiers to eliminate false positives.

- Gene-level Phasing: Grouping sequencing reads by haplotype using k-means clustering based on variant alleles weighted by quality scores.

- Allelic Linkage Testing: Quantifying allele-specific splicing ratios for each heterozygous gene by comparing splicing patterns between haplotypes.

- Classification: Designating exons with significant haplotype-biased inclusion as "cis-directed" and those with balanced inclusion across haplotypes as "trans-directed" [31].

This approach has revealed that genetic background significantly influences individual splicing profiles, with cis-directed events being particularly abundant in highly polymorphic regions like the HLA locus [31].

Diagram 2: isoLASER workflow for identifying cis- and trans-directed splicing events. Long-read RNA sequencing enables haplotype phasing and allele-specific splicing quantification, distinguishing events regulated by local genetic variants (cis) from those controlled by cellular environments (trans).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying SR Proteins and hnRNPs

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SR Protein Antibodies | mAb104, B52 | Immunodetection, immunoprecipitation | mAb104 recognizes phosphoepitope on RS domains; B52 binds SRSF6 [26] |

| Kinase Inhibitors | SRPK1 inhibitors, CLK inhibitors | Modulate SR protein phosphorylation | Affect nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and splicing activity [26] |

| SELEX Components | Random oligonucleotide library, Purified splicing factors | Defining RNA-binding specificity | Typically 5-15 selection rounds with increasing stringency [28] |

| Long-read Sequencing | PacBio Sequel II, Oxford Nanopore | Full-length isoform sequencing, haplotype phasing | Enables direct observation of complete splicing patterns [31] |

| Crosslinking Methods | UV crosslinking, CLIP variants | Mapping protein-RNA interactions in vivo | Critical for distinguishing direct versus indirect binding |

Functional Roles in Development and Disease

Tissue Development and Differentiation

SR proteins and hnRNPs exhibit distinct yet coordinated expression patterns during tissue development and differentiation. The brain represents a particularly complex regulatory environment, exhibiting the highest diversity of alternative splicing events among human tissues [25]. hnRNPs such as hnRNP H and F regulate the proteolipid protein (PLP/DM20) ratio in oligodendrocytes by modulating U1 snRNP recruitment, with implications for myelin formation and maintenance [3]. Similarly, PTBP1 (hnRNP I) and PTBP2 control neurodevelopmental transitions through regulated splicing of transcripts encoding synaptic proteins and ion channels [2].

In stem cells, hnRNPs maintain pluripotency and regulate differentiation through multiple mechanisms including alternative splicing of transcription factors, mRNA stability control, and telomere maintenance [27]. For example, hnRNP A1 regulates the alternative splicing of FOXP1 to produce isoforms that differentially influence embryonic stem cell differentiation [27].

Implications for Human Disease

Dysregulation of SR proteins and hnRNPs contributes significantly to human disease pathogenesis. In cancer, aberrant expression of splicing factors promotes oncogenic transformation through multiple mechanisms: generating proliferative isoforms of oncogenes, inactivating tumor suppressors via alternative splicing, and enhancing angiogenesis and metastasis [2]. SRSF1 is frequently overexpressed in tumors and promotes alternative splicing of BIN1, MNK2, and other cancer-relevant transcripts [2].

Neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders represent another major category of splicing factor-related pathologies. Mutations in hnRNP genes cause neurological syndromes including intellectual disability, epilepsy, microcephaly, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and frontotemporal dementia [25]. The particular vulnerability of neural tissues to splicing defects reflects the exceptionally complex alternative splicing patterns required for neuronal development and function [25].

Table 4: Splicing Factor Dysregulation in Human Disease

| Splicing Factor | Related Diseases | Molecular Mechanisms | Therapeutic Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRSF1 | Various cancers, Ataxia telangiectasia | Oncogenic isoform switching; disrupted DNA damage response | SRPK1 inhibitors; antisense oligonucleotides |

| hnRNP A1 | ALS, FTD, Alzheimer's disease | Altered splicing of tau and other neuronal transcripts; toxic nuclear aggregates | Small molecule inhibitors; modulators of autoregulation |

| hnRNP H | Familial ALS, Frontotemporal dementia | Dysregulation of cryptic exon inclusion in neurodegeneration genes | Antisense oligonucleotides targeting pathogenic exons |

| TRA2B | Spinal muscular atrophy | Impaired SMN2 exon 7 inclusion contributing to SMN protein deficiency | Splicing-switching oligonucleotides (Nusinersen) |

Concluding Perspectives

The intricate regulatory networks governed by SR proteins and hnRNPs represent a crucial layer of gene expression control that expands the functional complexity of eukaryotic genomes. Ongoing research continues to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms through which these factors recognize their RNA targets, recruit the splicing machinery, and integrate with other gene regulatory pathways. Emerging technologies—particularly long-read sequencing, improved proteomic methods, and single-cell approaches—promise to reveal unprecedented detail about splicing regulation in different cellular contexts and disease states.

Therapeutic targeting of splicing factors and their regulatory networks represents a promising frontier for treating numerous human diseases. Several strategies show considerable potential: small molecule inhibitors of splicing factor kinases (e.g., SRPK1), antisense oligonucleotides that modulate splicing of specific disease-relevant transcripts, and compounds that directly disrupt protein-RNA interactions. As our understanding of SR proteins and hnRNPs continues to deepen, these regulatory proteins will undoubtedly yield new insights into fundamental biology and provide innovative approaches for precision medicine.

The expression of eukaryotic genes requires the precise coordination of transcription and pre-mRNA splicing. For the majority of human genes, these processes are functionally coupled, with RNA Polymerase II (Pol II) playing a central role in orchestrating splicing alongside transcription. This coupling enables the regulation of alternative splicing, which affects over 95% of human genes and dramatically expands proteomic diversity. This technical review examines the molecular mechanisms underlying co-transcriptional splicing coupling, focusing on spatial and kinetic models mediated by Pol II, with implications for understanding gene regulation and developing therapeutic interventions for splicing-related diseases.

In eukaryotes, the separation of transcription and translation necessitates sophisticated RNA processing mechanisms. Pre-mRNA splicing, the removal of non-coding introns and ligation of coding exons, represents a critical step in gene expression. Historically viewed as a post-transcriptional event, substantial evidence now demonstrates that splicing occurs predominantly co-transcriptionally [32] [33]. This paradigm shift recognizes that the physiological substrate for splicing is not a full-length, freely diffusible pre-mRNA, but a nascent RNA chain growing at approximately 0.5-4 kb/min as it emerges from the transcribing Pol II complex [34] [35].

The C-terminal domain (CTD) of Pol II's largest subunit serves as a central platform for coordinating RNA processing. This unique appendage, consisting of 52 tandem repeats of the heptad sequence YSPTSPS in humans, undergoes dynamic phosphorylation during the transcription cycle, creating distinct binding surfaces for processing factors at different transcriptional stages [32] [33]. The coordination between transcription and splicing has profound implications for alternative splicing regulation, which generates multiple mRNA isoforms from single genes and affects approximately 95% of human genes [34] [35].

Molecular Mechanisms of Coupling

Spatial Coupling: Recruitment via the Pol II CTD

Spatial coupling ensures that splicing factors are positioned at the right place and time during transcription through direct physical interactions with the transcription machinery. The phospho-CTD code dictates the recruitment of specific processing factors throughout the transcription cycle [34] [35].

Table 1: CTD Phosphorylation States and Splicing Factor Recruitment

| Phosphorylation Site | Transcription Stage | Recruited Splicing Factors | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ser5-P | Promoter-proximal | U1 snRNP, SR proteins | Enhanced early spliceosome assembly [33] |

| Ser2-P | Elongation | U2AF65, U2 snRNP | Stabilization of 3' splice site recognition [34] |

| Ser7-P | Initiation/Elongation | Unknown splicing factors | Potential role in integrator recruitment [32] |

The CTD directly facilitates the recruitment of key splicing components. Inhibition of Ser2 phosphorylation reduces co-transcriptional splicing and impairs recruitment of U2AF65 and U2 snRNP [34]. The FUS protein, a regulator of alternative splicing, binds the CTD and helps maintain Ser2 phosphorylation, while acting as an adaptor for U1 snRNP binding to Pol II [34]. Beyond the CTD, the mediator complex influences alternative splicing through its Med23 subunit contacting splicing factors hnRNPL, SF3B, and Eval1 [34].

Figure 1: Spatial coupling mechanism showing Pol II CTD-mediated recruitment of splicing factors to nascent RNA

Kinetic Coupling: Transcription Elongation Rate

Kinetic coupling links the speed of transcription elongation with alternative splicing outcomes through a "window of opportunity" or "first come, first served" model [34] [35]. According to this model, when upstream and downstream splice sites compete for pairing partners, the upstream site gains a competitive advantage when elongation is slow, as splicing factors have more time to recognize and assemble on suboptimal splice sites before downstream competitors emerge.

Table 2: Effects of Elongation Rate on Alternative Splicing Outcomes

| Elongation Rate | Splicing Outcome | Proposed Mechanism | Example Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow | Increased inclusion of alternative exons | Extended window for weak splice site recognition | Fibronectin, NCAM [34] |

| Slow | Enhanced exon skipping | Extended window for negative regulator binding | CFTR exon 9 (ETR-3 binding) [34] |

| Fast | Altered splice site competition | Reduced time for regulatory factor binding | Genome-wide effects [34] |

| Optimal ("Goldilocks") | Proper splicing balance | Neither too fast nor too slow elongation | Majority of rate-sensitive exons [34] |

Unexpectedly, genome-wide studies using Pol II rate mutants revealed that many alternative exons require an optimal elongation rate that is "just right" – neither too fast nor too slow – suggesting a "Goldilocks" model for kinetic coupling [34]. This model posits that proper splicing regulation requires precise tuning of elongation rates within specific boundaries.

Chromatin and Spliceosome Connections

Chromatin Landscape Influences Splicing

The chromatin template plays an active role in regulating co-transcriptional splicing through several interconnected mechanisms. Nucleosome positioning exhibits a striking pattern of enrichment at exons compared to introns, creating a "punctuation" mark that may help signal exon boundaries to the splicing machinery [35]. This nucleosome positioning is influenced by higher GC content in exonic regions and contributes to transcriptional pausing that facilitates splice site recognition.

Multiple histone modifications show differential distributions between exons and introns. Exons are enriched for H3K36me3, H3K27me1/2/3, and H4K20me1, while introns show relative enrichment of H3K4me1/2, H3K9me1, and H3K79me1/2/3 [35]. These modifications can influence splicing decisions through both kinetic mechanisms (by affecting Pol II elongation rates) and spatial mechanisms (by recruiting splicing regulators).

The functional significance of chromatin in splicing regulation is demonstrated by the effects of chromatin-modifying enzymes. Inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) alters alternative splicing patterns in a manner dependent on Pol II elongation rate [35]. Similarly, the histone methyltransferase SETD2, which creates H3K36me3 marks, influences splicing decisions when tethering experiments position it to a specific gene [35].

Spliceosome Assembly Pathways