Autosomal Dominant vs Recessive Inheritance: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Applications, and Implications for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance patterns for researchers and drug development professionals.

Autosomal Dominant vs Recessive Inheritance: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Applications, and Implications for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance patterns for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational genetic mechanisms, distinctive pedigree features, and molecular consequences such as gain-of-function versus loss-of-function effects. The content covers methodological applications in genetic testing and clinical diagnosis, addresses complex challenges including reduced penetrance and genetic heterogeneity, and examines how inheritance patterns inform therapeutic target selection and drug development strategies. By integrating classical Mendelian principles with contemporary genetic evidence and clinical trial data, this resource aims to bridge the gap between genetic discovery and therapeutic innovation for monogenic disorders.

Mendelian Foundations: Decoding Autosomal Dominant and Recessive Inheritance Mechanisms

The principles of inheritance, first meticulously outlined by Gregor Mendel in the 1860s, form the indispensable cornerstone of modern genetics research and its therapeutic applications [1] [2]. His experiments with pea plants established fundamental laws that explain the transmission of traits from parents to offspring, principles that remain vitally relevant in contemporary studies of genetic disorders and drug development [2] [3]. Mendel's work introduced the concept of discrete "unit factors" – now known as genes – which maintain their integrity across generations and segregate predictably during reproduction [1]. This framework provides the essential logic for understanding how genetic information is transmitted and expressed, a foundation upon which all complex genetic analysis is built.

Within the context of autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance research, Mendel's Law of Segregation and Law of Dominance provide the predictive power to determine inheritance patterns of monogenic disorders [2] [4]. The Law of Segregation elucidates the mechanism by which alleles separate into gametes, ensuring that each parent contributes only one allele for each trait to their offspring [1] [5]. Concurrently, the Law of Dominance describes the interaction between these paired alleles in a heterozygous individual, where the presence of a single dominant allele can mask the expression of a recessive counterpart [6] [4]. For research scientists and drug development professionals, a precise understanding of these laws is not merely academic; it is critical for identifying disease-causing genes, calculating recurrence risks in families, and selecting the correct therapeutic strategy, such as determining whether to inhibit or activate a specific gene product [3] [7].

Core Principle I: The Law of Segregation

Conceptual Definition and Genetic Mechanism

The Law of Segregation, also known as Mendel's first law, states that an individual's two alleles for a given gene separate (segregate) during the formation of gametes [1] [4]. Consequently, each gamete carries only one allele for each gene, and the union of two gametes during fertilization restores the paired (diploid) condition in the offspring [1]. This law is frequently termed the "law of purity of gametes" because the two alleles for a trait do not blend or contaminate each other; they remain distinct and are separated cleanly during gametogenesis [1].

The biological basis for this segregation lies in the process of meiosis [1]. During anaphase I of meiosis, homologous chromosomes, each carrying one allele of the gene, are pulled to opposite poles of the cell. Subsequently, in anaphase II, sister chromatids separate. This meticulous chromosomal division ensures that the resulting gametes (sperm or egg cells) are haploid, containing only one set of chromosomes and, therefore, only one allele for every genetic locus [1]. The separation of allele pairs during gamete formation is a fundamental mechanism that ensures genetic variation and provides a pathway for recessive alleles to be carried silently in one generation and expressed in the next [4].

Experimental Foundation and Evidence

Mendel's monohybrid cross experiments provided the first empirical evidence for the Law of Segregation [4]. In one classic experiment, he crossed pure-breeding (homozygous) tall pea plants with pure-breeding dwarf pea plants. The resulting first filial (Fâ‚) generation consisted entirely of tall plants, consistent with the Law of Dominance. However, when Mendel then self-pollinated these Fâ‚ hybrid plants, the recessive dwarf phenotype reappeared in the second (Fâ‚‚) generation in a predictable 3:1 phenotypic ratio (three tall to one dwarf) [4].

The reappearance of the recessive trait in the Fâ‚‚ generation was the critical observation that demonstrated segregation. It proved that the hereditary factors for dwarfism had not been lost, altered, or blended in the Fâ‚ generation but had instead been temporarily masked and then segregated into separate gametes [4]. The genotypic ratio underlying the 3:1 phenotypic ratio is 1:2:1 (1 homozygous dominant : 2 heterozygous : 1 homozygous recessive) [6].

Table 1: Expected Genotypic and Phenotypic Outcomes from a Monohybrid Cross

| Generation | Parental Cross | Fâ‚ Genotype | Fâ‚ Phenotype | Fâ‚‚ Genotypic Ratio | Fâ‚‚ Phenotypic Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | TT x tt | Tt (100%) | Tall (100%) | 1 TT : 2 Tt : 1 tt | 3 Tall : 1 Dwarf |

The following diagram illustrates the chromosomal basis of allele segregation during meiosis, which underpins the phenotypic observations in Mendelian crosses:

Core Principle II: The Law of Dominance

Conceptual Definition and Allelic Interaction

The Law of Dominance states that in a heterozygous individual, one allele (the dominant allele) may mask the expression of the other allele (the recessive allele) [6] [4]. The physical expression, or phenotype, of the heterozygote is therefore identical to that of an individual homozygous for the dominant allele [2]. For a recessive trait to be expressed, the individual must inherit two copies of the recessive allele (homozygous recessive) [6]. This law explains why certain traits can appear to "skip" a generation, remaining unexpressed in heterozygous carriers (who display the dominant phenotype) only to reappear in offspring who inherit the recessive allele from both parents [4].

It is crucial to understand that dominance is a property of the phenotype, not the allele itself [6]. An allele is labeled dominant because of its effect when paired with a different allele in a heterozygote. The molecular basis of dominance often lies in the function of the protein the allele encodes; a dominant allele typically produces a functional protein (or a protein with altered function) that dictates the phenotype, even in the presence of a recessive allele that may produce a non-functional or less effective protein [6].

Clinical and Research Implications in Inheritance Patterns

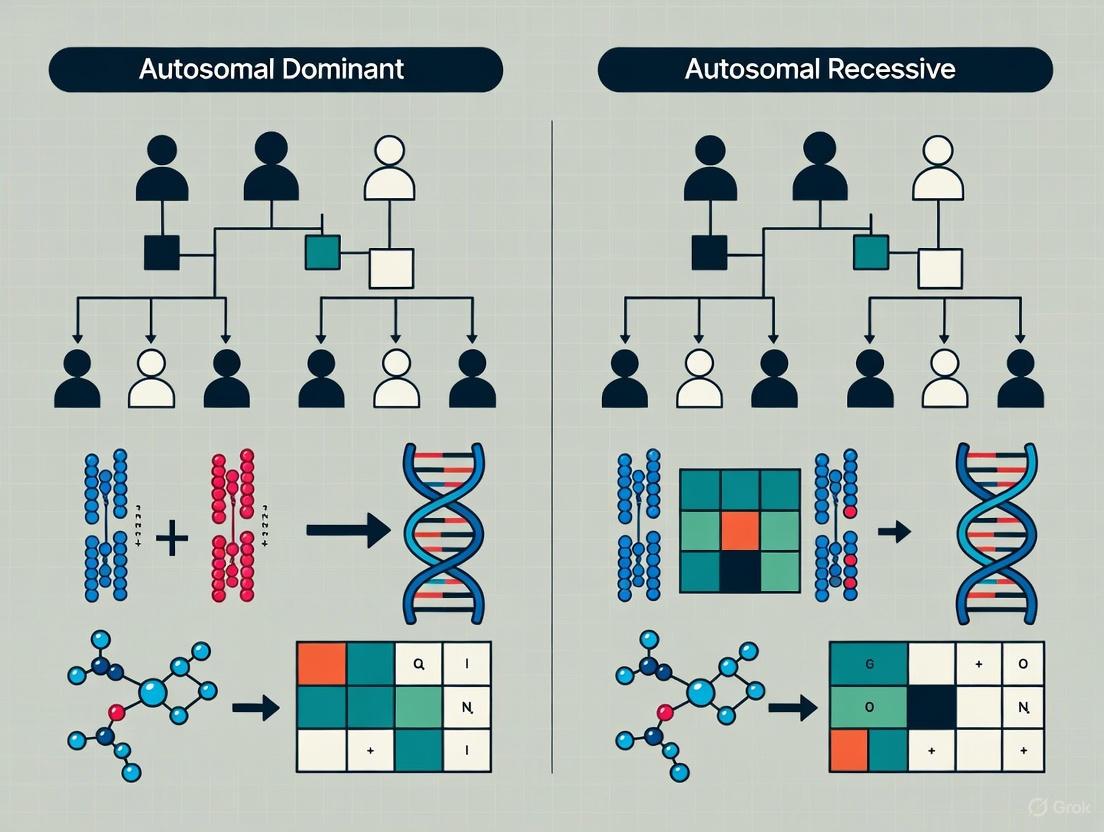

The Law of Dominance directly informs the clinical understanding of autosomal dominant and recessive disorders [2]. In autosomal dominant (AD) disorders, a single copy of a mutant allele is sufficient to cause the disease phenotype. An affected individual typically has a 50% chance of passing the disorder to each offspring [2]. In contrast, autosomal recessive (AR) disorders require two mutant alleles for the disease to manifest. Individuals with only one mutant allele are carriers; they are typically asymptomatic but can pass the mutant allele to their children [2].

Table 2: Characteristics of Autosomal Dominant vs. Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

| Feature | Autosomal Dominant (AD) | Autosomal Recessive (AR) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Mutant Alleles to Express Disease | One | Two |

| Typical Family Pedigree Pattern | Appears in every generation; does not skip [2] | May skip generations; often seen in a single sibship [8] |

| Parental Genotype of an Affected Individual | Usually one affected (heterozygous) parent | Both parents are typically asymptomatic carriers (heterozygous) |

| Recurrence Risk for Offspring of an Affected Parent | 50% | 0% (unless the other parent is a carrier) |

| Consanguinity | Not a significant factor | Increases risk [8] |

| Example Disorders | Marfan Syndrome [2], Tuberous Sclerosis [2] | Cystic Fibrosis, Sickle Cell Anemia [8] |

Modern genomic research confirms these patterns on a large scale. Studies of developmental disorders have shown that genes involved in autosomal dominant disorders are enriched for both activator and inhibitor drug targets, whereas genes involved in autosomal recessive disorders are depleted for inhibitor mechanisms, reflecting their underlying loss-of-function pathology [3].

Research Applications and Advanced Methodologies

Experimental Protocols for Validating Inheritance Patterns

Determining the mode of inheritance for a novel genetic variant or confirming a gene-disease association requires robust experimental and analytical protocols. The following methodologies are central to this research.

1. Family-Based Linkage Analysis and Trio-Based Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing: This is a primary method for identifying disease-causing variants and establishing inheritance patterns [8] [7]. The process begins with the collection of biological samples (typically blood or saliva) from a proband (the initial affected individual) and their parents (a "trio") and often extends to other affected and unaffected family members. DNA is extracted and subjected to high-throughput sequencing. Bioinformatic pipelines then align sequences to a reference genome, call variants, and filter them against population databases (e.g., gnomAD) to remove common polymorphisms. The analysis focuses on identifying:

- De novo variants (absent in parents' genomes) for dominant conditions.

- Compound heterozygous or homozygous recessive variants consistent with AR inheritance [8].

- Segregation of the candidate variant with the disease phenotype across the family pedigree.

2. Gene Burden Testing for Recessive Disorders: In large cohort studies, researchers quantify the burden of recessive coding variants by comparing the observed number of rare, damaging biallelic genotypes (homozygous or compound heterozygous) in cases versus the number expected by chance, using GIA group-specific allele frequencies and autozygosity levels [8]. A significant excess in cases indicates a recessive contribution to the disorder. This approach has shown that the attributable fraction of developmental disorders due to autosomal recessive coding variants can range from ~2% to over 18%, strongly correlating with the average autozygosity of the population [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Genetic Inheritance Research

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function and Application in Inheritance Studies |

|---|---|

| Trios and Family Pedigrees | The fundamental biological material for establishing co-segregation of genotypes and phenotypes and determining inheritance patterns [8]. |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing Kits | Enable comprehensive identification of single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number variants (CNVs) across the genome [8]. |

| Population Genomics Databases (e.g., gnomAD) | Provide allele frequencies across diverse populations, which is critical for filtering out common polymorphisms and assessing variant pathogenicity [8]. |

| Gene Intolerance Metrics (e.g., LOEUF) | Quantify a gene's tolerance to loss-of-function variants. Lower scores indicate higher constraint, a hallmark of genes associated with dominant disorders [3] [7]. |

| Disease Gene Databases (e.g., OMIM, DDG2P) | Curated repositories of known gene-disease relationships and their established inheritance patterns, used for validation and seed gene selection in machine learning models [7]. |

| Machine Learning Models (e.g., mantis-ml) | Semi-supervised frameworks that integrate genetic features (intolerance, expression) to predict novel risk genes in an inheritance-specific manner, accelerating gene discovery [7]. |

Application in Drug Development and Target Validation

Understanding inheritance patterns is critical for determining the direction of effect (DOE) for a potential drug target—that is, whether to inhibit or activate the target protein for therapeutic benefit [3]. Genetic evidence directly informs this decision:

- If gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in a gene increase disease risk, this suggests that inhibitor drugs are the appropriate therapeutic strategy.

- Conversely, if loss-of-function (LOF) mutations cause the disease, it may indicate that activator drugs or protein replacement therapies are needed [3].

Recent computational frameworks now predict DOE-specific druggability by integrating genetic associations, gene embeddings, and protein features [3]. These models have revealed distinct characteristics between activator and inhibitor targets; for instance, inhibitor drug targets tend to be more intolerant to LOF variation (lower LOEUF scores) and are enriched for genes involved in autosomal dominant disorders [3]. The following workflow diagram summarizes how genetic principles inform the drug target discovery pipeline:

Mendel's Law of Segregation and Law of Dominance are far more than historical concepts; they are dynamic principles that continue to underpin cutting-edge research in human genetics and therapeutic development [2] [3]. The Law of Segregation provides the mechanistic basis for the transmission of genetic variants, while the Law of Dominance explains the resulting phenotypic expression, forming the logical framework for distinguishing between autosomal dominant and recessive disorders [2] [4].

The integration of these principles with modern genomic technologies—such as large-scale trio sequencing, burden testing, and inheritance-aware machine learning models—is dramatically accelerating the pace of gene discovery and the validation of novel drug targets [8] [7]. For researchers and drug developers, a deep and functional understanding of these core genetic principles is not optional but essential. It enables the correct interpretation of genetic data, informs the prediction of disease risk, and critically, guides the strategic selection of therapeutic modality, ultimately paving the way for more precise and effective genetic medicine.

Autosomal dominant (AD) inheritance represents a fundamental pattern of genetic transmission in human genetics, wherein a single pathogenic variant on one allele is sufficient to cause disease phenotype. This comprehensive review elucidates the molecular mechanisms underlying AD disorders, explores their distinctive inheritance patterns characterized by vertical transmission across generations, and examines the clinical implications for disease diagnosis and management. Through detailed analysis of quantitative genetic data, experimental methodologies, and visualization of biological pathways, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with advanced insights into AD pathology. The discussion is contextualized within broader patterns of Mendelian inheritance, highlighting both the classical understanding of AD transmission and emerging complexities that challenge traditional classification paradigms, including genes exhibiting dual autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance patterns.

Autosomal dominant inheritance constitutes a major category of Mendelian disorders where mutation of a single allele on an autosome (chromosomes 1-22) is sufficient to manifest disease phenotype [9] [2]. This pattern contrasts sharply with autosomal recessive disorders, which require biallelic mutations for clinical expression. The term "autosomal" distinguishes these conditions from sex-linked disorders, while "dominant" indicates that the heterozygous state (one wild-type allele and one mutant allele) produces clinical disease [10]. In AD inheritance, males and females are equally likely to inherit and transmit the disorder, and male-to-male transmission can occur, which distinguishes it from X-linked inheritance patterns [2] [11].

The clinical significance of AD disorders extends beyond their inheritance pattern, as they include numerous conditions with substantial morbidity and mortality. Approximately 50% of known Mendelian disorders in humans follow an AD pattern [9]. Understanding the molecular basis and inheritance characteristics of these disorders is crucial for genetic counseling, risk assessment, diagnostic approaches, and the development of targeted therapies. This article explores the mechanistic foundations of AD disorders, their distinguishing features within the spectrum of inheritance patterns, and the experimental frameworks used in their investigation.

Core Mechanisms of Single-Allele Pathogenicity

Molecular Pathways to Dominance

In autosomal dominant disorders, pathogenicity arises through several distinct molecular mechanisms even when only a single allele carries a pathogenic variant. The primary mechanisms include haploinsufficiency, dominant-negative effects, and gain-of-function mutations [12]. Each mechanism disrupts normal cellular function through different pathways, though all result in a dominant phenotype despite the presence of one normal allele.

Haploinsufficiency occurs when a single functional copy of a gene cannot produce sufficient protein to maintain normal function [12]. In these cases, a 50% reduction in protein levels resulting from heterozygosity for a loss-of-function allele is sufficient to cause disease. This mechanism operates in disorders such as Marfan syndrome, where mutations in the FBN1 gene lead to defective fibrillin, an essential component of the extracellular matrix [2]. The insufficient production of functional fibrillin disrupts the structural integrity of connective tissue, resulting in the characteristic clinical manifestations including cardiovascular, skeletal, and ocular abnormalities.

Dominant-negative effects occur when a mutant gene product interferes with the function of the wild-type allele product within the same cell [9]. This mechanism is particularly common in disorders involving multimeric proteins, where the incorporation of even a single mutant subunit can disrupt the function of the entire protein complex. For example, in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2 genes produce defective hamartin or tuberin proteins that dysregulate the mTOR signaling pathway through dominant-negative effects on the TSC protein complex [2].

Gain-of-function mutations confer novel or enhanced activity on a gene product, often leading to toxic effects regardless of the presence of a normal allele [9]. This mechanism operates in disorders such as Huntington disease, where expansion of a triplet repeat within a polyglutamine tract causes cellular toxicity through acquired toxic functions of the mutant huntingtin protein [9]. Similarly, specific mutations can lead to constitutive activation of signaling pathways, disrupting normal cellular regulation and proliferation.

Table 1: Molecular Mechanisms in Autosomal Dominant Disorders

| Mechanism | Molecular Consequence | Example Disorders | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haploinsufficiency | Reduced protein levels below functional threshold | Marfan syndrome (FBN1), AD polycystic kidney disease (PKD1/PKD2) | 50% reduction in functional protein sufficient for disease manifestation |

| Dominant-negative | Mutant protein disrupts function of wild-type protein | Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1/TSC2), some collagen disorders | Common in multimeric proteins; mutant subunit disrupts entire complex |

| Gain-of-function | Novel or enhanced protein activity with toxic effects | Huntington disease, achondroplasia | Toxic activity regardless of normal allele; often constitutive activation |

| Altered regulation | Disrupted gene expression or splicing | Some forms of familial hypercholesterolemia (LDLR) | May affect promoter regions, splicing sites, or regulatory elements |

Genetic Principles and Allelic Effects

Autosomal dominant inheritance follows Mendel's Law of Dominance and Uniformity, which states that some alleles are dominant over others, and thus mask the recessive allele when both are present [2]. The Law of Segregation further dictates that the two alleles for each gene separate during gametogenesis, so each parent passes only one allele to offspring [2]. This fundamental genetic principle explains the 50% transmission risk from an affected parent to each child, regardless of gender.

An important characteristic of many AD disorders is complete penetrance, meaning that all individuals who inherit the pathogenic variant will eventually express the disease phenotype [9]. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) exemplifies this principle, as virtually all carriers of pathogenic PKD1 or PKD2 variants develop characteristic renal cysts during their lifetime [9]. However, AD disorders also demonstrate variable expressivity, wherein the severity and specific features of the disease vary among individuals with the same mutation, even within the same family [9]. This variability reflects the influence of modifier genes, environmental factors, and stochastic events on disease manifestation.

Some AD disorders exhibit incomplete penetrance, where not all individuals with the pathogenic variant develop clinical disease [10]. This is particularly evident in inherited cancer susceptibility syndromes, such as those involving BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, where penetrance figures for BRCA1 are approximately 60% for breast cancer and 40% for ovarian cancer, far from complete penetrance [9]. The concepts of penetrance and expressivity have critical implications for genetic counseling, risk assessment, and clinical management.

Vertical Transmission Patterns in Pedigree Analysis

Characteristic Pedigree Patterns

The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern displays distinctive features in pedigree analysis that facilitate its recognition and differentiation from other inheritance patterns. The most prominent characteristic is vertical transmission, wherein the phenotype appears in multiple generations without skipping [2] [11]. This pattern emerges because each affected individual typically has an affected parent, except in cases of de novo mutations or reduced penetrance.

Additional hallmark pedigree characteristics of AD inheritance include:

- Equal distribution between sexes: Males and females are equally likely to inherit and transmit the disorder [10] [11]

- Male-to-male transmission: Affected males can transmit the disorder to their sons, distinguishing AD inheritance from X-linked dominant inheritance [11]

- 50% transmission risk: Each child of an affected individual has a 50% chance of inheriting the pathogenic variant and the disorder [10] [2]

- Absence of carrier state: Individuals with the pathogenic variant are affected; there are no asymptomatic carriers [9]

The following diagram illustrates the characteristic pedigree pattern of autosomal dominant inheritance:

Exceptions and Complexities in Transmission

While the vertical transmission pattern typically characterizes AD inheritance, several factors can complicate pedigree interpretation and create apparent deviations from the expected pattern. Incomplete penetrance occurs when an individual inherits a pathogenic variant but does not manifest clinical symptoms, creating the appearance of skipped generations [10] [2]. For example, in hereditary cancer syndromes, not all variant carriers develop cancer during their lifetime, potentially obscuring the inheritance pattern.

De novo mutations represent another exception, wherein the pathogenic variant arises spontaneously in an affected individual with no family history of the disorder [2]. Many AD disorders arise frequently from de novo mutations, including an estimated 70% of tuberous sclerosis complex cases [2]. In such cases, the recurrence risk for siblings of the affected individual is low, but the affected individual themselves now face the 50% transmission risk to their offspring.

Germline mosaicism occurs when a parent carries the pathogenic variant in their germline cells but not in somatic cells, allowing them to have multiple affected children without being affected themselves [2]. This phenomenon can create patterns that resemble autosomal recessive inheritance but with higher recurrence risks than typically associated with de novo mutations.

Phenocopies represent another complicating factor, wherein individuals without the pathogenic variant develop similar clinical features through alternative mechanisms [10]. In breast cancer families with BRCA mutations, for instance, sporadic breast cancer cases in non-carriers can create the false impression of reduced penetrance or misassign affected status in pedigree analysis.

Table 2: Transmission Patterns in Autosomal Dominant vs. Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

| Characteristic | Autosomal Dominant | Autosomal Recessive |

|---|---|---|

| Generational pattern | Vertical transmission across generations | Horizontal transmission (often single generation) |

| Carrier status | No carriers; all variant holders affected | Asymptomatic carriers common |

| Parental affected status | Usually one affected parent | Both parents typically unaffected carriers |

| Recurrence risk | 50% for offspring of affected individual | 25% for offspring of carrier parents |

| Consanguinity | Not a significant factor | Increases recurrence risk |

| Sex distribution | Equal in males and females | Equal in males and females |

| Male-to-male transmission | Possible | Possible |

Experimental Methodologies for Analysis

Genetic Testing Approaches

The investigation of autosomal dominant disorders employs specialized genetic testing methodologies designed to identify pathogenic variants in single alleles. Single-gene tests represent the most targeted approach, sequencing or analyzing specific genes associated with known clinical presentations [13]. For patients with characteristic features of a specific AD disorder, such as Marfan syndrome or neurofibromatosis type 1, single-gene testing provides a direct and cost-effective diagnostic pathway.

Gene panel testing utilizes next-generation sequencing to simultaneously examine multiple genes associated with particular clinical presentations or organ systems [13]. This approach is particularly valuable for genetically heterogeneous disorders, such as inherited cardiac conditions or hereditary cancer syndromes, where mutations in numerous different genes can produce similar phenotypes. Panel testing offers the advantage of comprehensive assessment while maintaining focused analysis on clinically relevant genes.

Large-scale genetic tests, including whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS), provide the most extensive analysis of an individual's genetic material [13]. WES examines the protein-coding regions of all genes, while WGS extends to non-coding regions as well. These approaches are particularly valuable for diagnosing atypical presentations or conditions with unknown genetic etiology. The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for genetic testing in autosomal dominant disorders:

Functional Validation of Pathogenic Variants

Following genetic testing and variant identification, functional studies are often necessary to establish the pathogenicity of identified variants, particularly for novel or previously uncharacterized mutations. In vitro assays assess the functional consequences of mutations in controlled laboratory settings, using cell cultures or biochemical systems to evaluate protein function, stability, or interaction properties.

Molecular modeling utilizes computational approaches to predict the structural impact of mutations on protein folding, binding sites, or enzymatic activity. This approach is particularly valuable for missense variants of uncertain significance, where changes in amino acid sequence may alter protein structure and function.

Animal models, particularly genetically modified mice, provide systems for studying the in vivo consequences of pathogenic variants and exploring potential therapeutic interventions. These models recapitulate aspects of human disease and allow investigation of pathogenetic mechanisms across developmental stages and tissue types.

For disorders demonstrating dual inheritance patterns (both autosomal dominant and recessive), additional functional studies are required to elucidate the molecular basis of these contrasting patterns [12]. Such genes may exhibit distinct genotype-phenotype correlations based on mutation type, position, or functional consequence, necessitating comprehensive biochemical and cellular characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Autosomal Dominant Disorders

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA Isolation Kits | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, PureLink Genomic DNA Kits | Source material for genetic testing; quality critical for sequencing success | Assess concentration, purity (A260/280), and integrity |

| PCR and Sequencing Reagents | Taq polymerase, dNTPs, Sanger sequencing kits, NGS library prep kits | Target amplification and sequencing for variant detection | Optimize annealing temperatures; validate primer specificity |

| Cell Culture Systems | Patient-derived fibroblasts, lymphoblastoid cell lines, iPSCs | Functional studies of pathogenetic mechanisms | Monitor for phenotypic drift in continuous culture |

| Antibodies | Wild-type and mutant protein-specific antibodies, phospho-specific antibodies | Protein expression analysis, localization studies, Western blot | Validate specificity using appropriate controls |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Components | Guide RNAs, Cas9 expression vectors, homology-directed repair templates | Generation of isogenic cell lines, animal models | Optimize delivery efficiency; screen for off-target effects |

| Protein Analysis Reagents | Co-immunoprecipitation kits, crosslinkers, protein stability assays | Assessment of protein-protein interactions, complex formation | Include appropriate controls for nonspecific interactions |

Emerging Concepts and Complex Inheritance Patterns

Genes with Dual Inheritance Patterns

Recent research has identified a subset of genes that demonstrate both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive inheritance patterns, challenging traditional Mendelian classification systems [12]. These "AD/AR genes" exhibit distinct bioinformatic properties, including intermediate constraint scores (metrics of tolerance to genetic variation), greater average numbers of exons, and an elevated propensity to encode proteins that form homomeric or heteromeric complexes [12].

The mechanistic basis for dual inheritance patterns varies among genes and disorders. In some cases, different mutation types (e.g., loss-of-function vs. missense mutations) or mutation locations within the gene produce distinct inheritance patterns. In other instances, the same mutation may exhibit both dominant and recessive patterns in different families or populations, reflecting the influence of genetic modifiers or environmental factors.

A notable example of this complexity is emerging in deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2), traditionally described as an autosomal recessive condition [14]. Recent evidence indicates that specific ADA2 variants can cause disease in heterozygous carriers through a dominant-negative mechanism, resulting in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance [14]. This finding has significant implications for diagnostic testing, genetic counseling, and family risk assessment.

Implications for Genetic Counseling and Drug Development

The complexities of autosomal dominant inheritance, including variable expressivity, incomplete penetrance, and emerging dual inheritance patterns, present significant challenges for genetic counseling. Risk assessment and communication must account for these nuances, emphasizing that inheritance patterns represent probabilities rather than certainties. For drug development, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying AD disorders informs targeted therapeutic strategies.

For haploinsufficiency disorders, therapeutic approaches may aim to upregulate expression from the wild-type allele or compensate for the deficient protein. For dominant-negative disorders, strategies that selectively silence mutant alleles while preserving wild-type expression (e.g., allele-specific RNA interference) hold promise. Gain-of-function disorders may benefit from approaches that directly inhibit the toxic protein or its downstream effects.

The investigation of autosomal dominant inheritance patterns continues to evolve with advancing technologies and accumulating clinical experience. Future research directions include comprehensive characterization of genes with dual inheritance patterns, elucidation of modifier genes that influence expressivity and penetrance, and development of targeted therapies that address the specific molecular consequences of dominant pathogenic variants. These advances will enhance diagnostic accuracy, refine risk prediction, and ultimately improve clinical outcomes for individuals and families affected by autosomal dominant disorders.

Autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance represents a fundamental pattern of Mendelian genetics where phenotypes manifest only when an individual inherits two mutated alleles of a gene, one from each parent [15] [16]. This mechanism underlies thousands of rare genetic disorders, collectively contributing significantly to pediatric morbidity and mortality worldwide [17]. Understanding AR inheritance is crucial for researchers, clinical geneticists, and drug development professionals working to diagnose, manage, and develop therapies for these conditions.

Within the broader context of inheritance pattern research, AR disorders contrast sharply with autosomal dominant (AD) conditions. While AD disorders typically appear in every generation (vertical transmission) and require only a single mutated allele for expression, AR disorders often skip generations and require biallelic mutations [16] [18]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the molecular mechanisms, inheritance patterns, diagnostic methodologies, and research considerations specific to autosomal recessive conditions.

Molecular Mechanisms and Genetic Principles

Fundamental Genetic Laws

Autosomal recessive inheritance follows Mendel's laws of inheritance, particularly the Law of Segregation, which states that each individual carries two alleles for each gene, which segregate during gamete formation [15]. Each parent passes one randomly selected allele to their offspring, resulting in a 25% chance for carrier parents to have an affected child [15].

The term "autosomal" specifies that the gene in question is located on one of the 22 autosomes (non-sex chromosomes) rather than the X or Y sex chromosomes [13]. "Recessive" indicates that both alleles must harbor pathogenic mutations for the disease phenotype to manifest [18].

Biallelic Mutations and Pathogenic Mechanisms

In AR disorders, disease expression requires biallelic mutations—pathogenic variants in both copies of a gene [15]. These mutations typically result in loss of function through various mechanisms:

- Complete gene deletion or inactivation

- Enzyme deficiencies due to catalytic impairment

- Structural protein defects affecting cellular function

Carriers (heterozygotes) with a single mutated allele are typically asymptomatic due to haplosufficiency, where the single functional allele produces sufficient protein to maintain normal cellular function [15]. This contrasts with many AD disorders where haploinsufficiency (inadequate protein from a single functional allele) or dominant-negative effects lead to disease manifestation in heterozygotes [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Inheritance Patterns

| Feature | Autosomal Recessive | Autosomal Dominant |

|---|---|---|

| Alleles Required | Two mutated alleles (biallelic) | One mutated allele (monoallelic) |

| Transmission Pattern | Horizontal (skips generations) | Vertical (every generation) |

| Carrier Status | Heterozygotes are typically asymptomatic | Heterozygotes are affected |

| Recurrence Risk | 25% for carrier parents | 50% for affected parents |

| Common Molecular Mechanisms | Complete loss-of-function | Haploinsufficiency, dominant-negative, gain-of-function |

| Consanguinity Effect | Significantly increases risk | Minimal effect on recurrence risk |

Inheritance Patterns and Pedigree Characteristics

AR disorders typically display horizontal transmission patterns within pedigrees, where multiple affected individuals may appear within the same generation (siblings) but not typically across generations [15]. This contrasts with the vertical transmission pattern characteristic of AD disorders [15].

Several key pedigree features characterize AR inheritance:

- Unaffected carrier parents: Both parents of an affected individual are typically heterozygous carriers [16]

- Sibling clusters: Multiple affected siblings within a single generation [15]

- Generational skipping: Affected individuals often have unaffected offspring [15]

- Consanguinity increase: Higher prevalence in consanguineous families due to shared ancestry [15] [19]

An exception to typical horizontal transmission occurs in pseudodominance, where an affected individual (homozygote) has children with a carrier (heterozygote), resulting in a 50% chance of affected offspring and creating a vertical transmission pattern that mimics AD inheritance [15].

Clinical and Research Considerations

Epidemiology and Population Genetics

AR disorders collectively represent a significant health burden worldwide. Current research indicates that approximately 1 in 300 pregnancies is affected by AR or X-linked conditions globally [20]. Carrier frequencies for AR disorders vary considerably across different populations due to founder effects, genetic drift, and in some cases, heterozygote advantage [15] [19].

Table 2: Carrier Frequencies of Selected Autosomal Recessive Disorders

| Disorder | Gene | Carrier Frequency | High-Risk Populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR | 1 in 30 | Caucasian, Ashkenazi Jewish [15] |

| Tay-Sachs Disease | HEXA | 1 in 27 | Ashkenazi Jewish, French Canadian [15] |

| Sickle Cell Anemia | HBB | 1 in 12 | African, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern [15] |

| Beta Thalassemia | HBB | 1 in 28 | Vietnamese, Mediterranean, Southeast Asian [20] |

| G6PD Deficiency | G6PD | 1 in 20 | Vietnamese, African, Mediterranean [20] |

| Alpha Thalassemia | HBA1/HBA2 | 1 in 25 | Vietnamese, Southeast Asian [20] |

Population isolates and endogamous groups demonstrate particularly high frequencies of specific AR disorders due to founder effects and genetic drift [19]. For example, the Roma population in Europe shows an elevated frequency of rare AR disorders, with researchers having identified 90 distinct AR disorders and 111 pathogenic variants in this population [19].

Some genes demonstrate both AD and AR inheritance patterns depending on the specific variant and its molecular consequences [12]. These "AD/AR genes" typically exhibit distinctive features including intermediate constraint scores, greater average number of exons, and an elevated propensity to form homomeric/heteromeric proteins [12].

Common Autosomal Recessive Disorders

Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

Caused by mutations in the CFTR gene on chromosome 7, CF affects approximately 1 in 1000 White births [15]. The disease affects exocrine glands, leading to lung infections, pancreatic insufficiency, and infertility [15]. The carrier frequency approaches 1 in 25 in Caucasian and Ashkenazi Jewish populations [15].

Hemoglobinopathies

Sickle cell disease and thalassemias represent common AR disorders affecting hemoglobin [15]. Sickle cell disease demonstrates incomplete dominance, where heterozygotes (sickle cell trait) exhibit an intermediate phenotype that provides protection against malaria, explaining its high frequency in malaria-endemic regions [15].

Tay-Sachs Disease

Caused by HEXA gene mutations, Tay-Sachs results in deficiency of hexosaminidase A, leading to GM2 ganglioside accumulation in the brain [15]. Affected infants experience progressive neurodegeneration, with death typically occurring in early childhood [15].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Carrier Screening and Molecular Diagnostics

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized carrier screening for AR disorders, enabling simultaneous testing for hundreds of conditions in a single assay [20] [17]. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommends a tiered approach to carrier screening, with Tier 3 screening (conditions with ≥1/200 carrier frequency) recommended for all pregnant patients [20].

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive Carrier Screening Using NGS

Sample Collection

- Collect 7-10 ml peripheral venous blood in EDTA tubes [20]

- Ensure proper sample labeling and storage at -20°C until processing

DNA Extraction

- Use validated DNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Micro Kit) [20]

- Quantify DNA concentration using fluorometric methods

- Assess DNA quality via agarose gel electrophoresis or similar methods

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Bioinformatic Analysis

Variant Interpretation and Classification

- Classify variants according to ACMG guidelines [17]

- Report pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants

- Provide carrier status and recurrence risk information

Variant Classification Framework

Research and clinical diagnostics for AR disorders employ sophisticated variant classification systems [17]:

Type 1 Variants: Known pathogenic variants from ClinVar database with established disease association [17]

Type 2 Variants: Presumed loss-of-function variants including:

- Stop-gained (nonsense) mutations

- Frameshift insertions/deletions

- Splice-site variants (acceptor/donor)

- Start-lost mutations [17]

Type 3 Variants: Predicted deleterious missense changes identified using multiple in silico prediction tools (CADD, DANN, Polyphen2, SIFT, phastCons) with established cutoff scores [17]

Type 4 Variants: Potentially harmful in-frame insertions or deletions [17]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Autosomal Recessive Disorder Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries from genomic DNA | Illumina Nextera, Twist Bioscience kits |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Platforms | Comprehensive variant discovery across entire genome | Illumina NextSeq, NovaSeq; PacBio Sequel |

| Targeted Gene Panels | Focused analysis of known AR genes | Custom panels for common AR disorders (CFTR, HEXA, HBB) |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Validation of NGS findings | BigDye Terminator chemistry, capillary electrophoresis |

| Cell Line Models | Functional studies of AR disease mechanisms | Patient-derived fibroblasts, iPSCs, gene-edited cell lines |

| Antibodies for Protein Analysis | Detection of protein expression and localization | Western blot, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene editing to create disease models | SpCas9, base editors, prime editors for specific mutations |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Variant calling, annotation, and prioritization | GATK, ANNOVAR, Varsome, ExpansionHunter |

| Population Databases | Allele frequency filtering and pathogenicity assessment | gnomAD, 1000 Genomes, dbSNP, ClinVar |

| Protein Prediction Software | In silico analysis of missense variant effects | CADD, PolyPhen-2, SIFT, AlphaFold2 |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Carrier Frequency Calculations

Research into AR disorders requires accurate calculation of carrier frequencies using large genomic datasets. The established pipeline involves [17]:

Cohort Selection: Utilize large-scale genomic databases (e.g., gnomAD) containing sequencing data from diverse populations [17]

Variant Filtering: Apply stringent quality control metrics and remove variants with:

- Alternative allele frequency ≥ 0.005

- Homozygous calls in presumed healthy individuals

- Poor sequencing quality metrics [17]

Population-Specific Analysis: Calculate carrier frequencies within distinct ethnic groups to account for population genetics differences [17]

Statistical Validation: Compare results across different cohorts with similar ethnicity backgrounds to verify findings (e.g., Pearson correlation coefficient >0.9 between Chinese cohorts) [17]

Pedigree Analysis and Risk Assessment

Accurate interpretation of family history remains crucial for AR disorder investigation:

- Carrier Identification: Asymptomatic individuals with family history of AR disorders

- Consanguinity Assessment: Document parental relatedness which significantly increases AR disorder risk [15] [19]

- Recurrence Risk Calculation: 25% for carrier parents, 50% in pseudodominance scenarios [15]

- Population Risk Integration: Combine family history with population-based carrier frequencies for comprehensive risk assessment

Autosomal recessive inheritance represents a genetically complex but well-characterized pattern of disease transmission with distinct molecular mechanisms and pedigree characteristics. The requirement for biallelic mutations and the resulting horizontal transmission pattern differentiate AR disorders from other inheritance models and present unique challenges for researchers and clinicians.

Advanced molecular techniques, particularly comprehensive carrier screening using NGS, have significantly improved our ability to identify at-risk couples and implement preventive strategies. Population-specific differences in carrier frequencies necessitate tailored approaches to genetic screening and counseling across different ethnic groups.

Ongoing research continues to expand our understanding of AR disorders, including the identification of novel disease genes, characterization of atypical inheritance patterns such as pseudodominance, and investigation of genes with dual AD/AR inheritance capabilities. These advances, coupled with improved therapeutic interventions, promise to reduce the global burden of autosomal recessive disorders through enhanced diagnosis, management, and prevention strategies.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of disease-causing genetic variants is fundamental to advancing genetic medicine. While numerous pathogenic mutations occur in protein-coding regions, they exert their effects through fundamentally different mechanisms: loss-of-function (LOF), gain-of-function (GOF), and dominant-negative (DN) effects [21]. These mechanisms are intimately connected to the inheritance patterns observed in genetic disorders. Autosomal recessive conditions are overwhelmingly associated with LOF mutations, where both gene copies must be impaired to cause disease [22]. In contrast, autosomal dominant disorders can arise through multiple molecular mechanisms, including LOF (haploinsufficiency), GOF, or DN effects, with significant implications for disease pathology and therapeutic development [23] [24].

The distinction between these mechanisms is not merely academic; it directly informs diagnostic approaches and therapeutic strategies. GOF and DN mutations account for approximately 48% of phenotypes in dominant genes, highlighting their clinical significance [23]. Furthermore, 43% of dominant and 49% of mixed-inheritance genes exhibit intragenic mechanistic heterogeneity, where different mutations within the same gene cause disease through distinct molecular mechanisms [23]. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of GOF and LOF mechanisms within the framework of inheritance patterns, integrating structural insights, computational predictions, and experimental methodologies.

Molecular Mechanisms and Inheritance Patterns

Autosomal Recessive Inheritance and Loss-of-Function Mechanisms

Autosomal recessive disorders require biallelic mutations that collectively result in complete or near-complete loss of gene function [22]. Affected individuals typically inherit one mutant allele from each parent, both of whom are usually asymptomatic carriers. This pattern reflects the fundamental principle that one functional allele is often sufficient to maintain normal cellular function, a concept known as haplosufficiency [15] [22].

In recessive disorders, LOF mutations primarily include nonsense variants (premature stop codons), frameshifts, splice-site disruptions, and missense mutations that severely destabilize protein structure or disrupt critical functional residues [22]. The resulting phenotypic manifestations occur only when the residual protein activity falls below a critical threshold necessary for normal physiological function.

Clinical Examples:

- Cystic fibrosis: Caused by mutations in the CFTR gene, leading to defective chloride ion transport [15] [22]

- Tay-Sachs disease: Results from HEXA gene mutations causing deficiency of hexosaminidase A and accumulation of GM2 ganglioside [15]

- Sickle cell disease: Caused by homozygous mutations in HBB leading to structural hemoglobin abnormalities [15] [22]

Table 1: Characteristics of Autosomal Recessive LOF Disorders

| Aspect | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Inheritance Pattern | Horizontal transmission within sibships, often with unaffected parents |

| Molecular Requirement | Biallelic mutations (homozygous or compound heterozygous) |

| Protein Impact | Severe structural destabilization or complete functional ablation |

| Carrier Status | Heterozygotes typically asymptomatic due to haplosufficiency |

| Consanguinity Effect | Increased recurrence risk in consanguineous families |

Autosomal Dominant Inheritance: Diverse Molecular Mechanisms

Autosomal dominant disorders manifest when a single mutant allele is sufficient to cause disease, through several distinct molecular pathways:

Haploinsufficiency (LOF)

In haploinsufficiency, a 50% reduction in protein activity due to a single LOF allele is insufficient to maintain normal function [2] [10]. This mechanism applies to genes where precise protein dosage is critical for biological activity, such as transcription factors or regulatory proteins [24].

Dominant-Negative (DN) Effects

DN mutations occur when a mutant subunit disrupts the function of a multimeric protein complex containing wild-type subunits [21] [24]. The mutant protein must be sufficiently stable to co-assemble with wild-type partners but functionally impaired enough to "poison" the entire complex. Structurally, DN mutations are highly enriched at protein-protein interfaces and tend to have milder destabilizing effects than recessive LOF mutations [21].

Gain-of-Function (GOF)

GOF mutations confer new or enhanced activities to the protein, including:

- Constitutive activation without normal regulatory constraints

- Altered binding specificity for substrates or interaction partners

- Novel toxic functions such as aggregation propensity [21] [25]

Unlike LOF mutations, GOF variants often cluster in specific functional domains and cause minimal protein destabilization [23].

Table 2: Molecular Mechanisms in Autosomal Dominant Disorders

| Mechanism | Structural Impact | Functional Consequence | Example Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haploinsufficiency (LOF) | Severe destabilization | Reduced protein dosage | Marfan syndrome (FBN1), Tuberous sclerosis (TSC1/TSC2) [2] |

| Dominant-Negative | Mild destabilization, interface disruption | Disruption of multimeric complexes | Collagenopathies, long QT syndrome [23] [24] |

| Gain-of-Function | Minimal destabilization, functional site alterations | Enhanced or novel protein activity | STAT1 GOF (chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis) [25] |

Structural and Computational Insights

Protein Structural Effects of Different Mechanisms

The structural consequences of pathogenic missense mutations vary dramatically between molecular mechanisms. Studies analyzing ΔΔG values (changes in Gibbs free energy of folding) reveal that recessive LOF mutations cause severe protein destabilization (average |ΔΔG| = 3.89 kcal molâ»Â¹), while dominant non-LOF mutations (DN and GOF) have markedly milder effects [21] [24]. This distinction arises because DN mutations must preserve the ability to co-assemble with wild-type subunits, while GOF mutations typically avoid global unfolding to maintain their altered function.

The structural location of mutations also differs between mechanisms. LOF mutations are distributed throughout protein structures, affecting both buried and surface residues critical for folding stability. In contrast, DN mutations cluster at protein-protein interfaces, and GOF mutations concentrate in functional domains such as active sites or regulatory regions [21] [23].

Consideration of full biological assemblies rather than isolated monomers significantly improves the identification of disease mutations, particularly for DN variants where intermolecular interactions are critical [21] [24]. This highlights the importance of structural context for understanding pathogenicity.

Computational Prediction of Molecular Mechanisms

Accurate computational prediction of variant effects remains challenging, particularly for non-LOF mechanisms. Most variant effect predictors (VEPs), including those based on sequence conservation, demonstrate reduced performance for DN and GOF mutations compared to LOF mutations [21] [25]. This limitation stems from the fundamental differences in structural constraints between mechanism types.

Recent advances integrate multiple structural features to improve mechanism prediction:

The mLOF Score

The missense LOF (mLOF) likelihood score integrates both the energetic impact (ΔΔG) and spatial clustering (Extent of Disease Clustering, EDC) of pathogenic variants [23]. This approach leverages the observation that LOF variants tend to be highly destabilizing and spread throughout the structure, while non-LOF variants cause milder destabilization and cluster in specific regions. The mLOF score achieves a balanced accuracy of 71.2% in distinguishing LOF from non-LOF mechanisms [23].

LoGoFunc

The LoGoFunc machine learning method represents a significant advancement in genome-wide prediction of GOF and LOF variants [25]. Trained on 474 diverse features derived from AlphaFold2-predicted structures, protein interaction networks, evolutionary constraints, and other biological characteristics, LoGoFunc outperforms general pathogenicity predictors for mechanism classification. The model employs an ensemble of LightGBM classifiers and provides precomputed predictions for all missense variants in canonical human transcripts [25].

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Mechanism Prediction Methods

| Method | Features | LOF vs Non-LOF AUROC | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability predictors (FoldX) | Absolute ΔΔG values | 0.677 [21] | Identifying destabilizing LOF mutations |

| mLOF Score | ΔΔGrank + EDC | 0.714 (single phenotype genes) [23] | Phenotype-level mechanism prediction |

| LoGoFunc | 474 diverse features (structural, evolutionary, network-based) | State-of-the-art for GOF/LOF classification [25] | Genome-wide variant interpretation |

Experimental Methodologies

Structure-Based Stability Assessments

Protein stability assays provide direct experimental evaluation of LOF mutations. The core methodology involves:

Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Protein Stability Assay Workflow

Protein Expression and Purification

- Express wild-type and variant proteins in appropriate systems (E. coli, mammalian cells)

- Purify using affinity chromatography (His-tag, GST-tag) followed by size exclusion chromatography

- Verify purity and monodispersity via SDS-PAGE and dynamic light scattering

Stability Measurements

- Thermal shift assays: Monitor fluorescence changes with temperature increase to determine melting temperature (Tₘ)

- Chemical denaturation: Use urea or guanidine HCl denaturation curves monitored by circular dichroism or fluorescence to calculate ΔG of unfolding

- Proteolytic sensitivity: Assess resistance to limited proteolysis as indicator of structural integrity

Data Analysis

- Calculate ΔΔG values between wild-type and variant proteins

- Correlate stability changes with functional impairments

- Classify variants as destabilizing (LOF) or stability-neutral (potential non-LOF)

For DN mutations, additional complex formation assays (co-immunoprecipitation, analytical ultracentrifugation, surface plasmon resonance) determine whether mutant subunits incorporate into multimers and inhibit wild-type function [21].

Functional Characterization of GOF Mutations

GOF mutations require specialized assays tailored to the specific gained function:

Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: GOF Variant Characterization

Cellular Assays

- Constitutive signaling: Measure downstream pathway activation in absence of normal stimuli (e.g., phospho-specific antibodies, reporter gene assays)

- Altered localization: Visualize subcellular distribution using immunofluorescence or live-cell imaging with GFP-tagged proteins

- Aggregation propensity: Assess protein solubility and aggregation using filter trap assays or microscopy

Biochemical Assays

- Enzyme kinetics: Determine KM, Vmax, and catalytic efficiency for enzymatic GOF variants

- Binding affinity: Quantify interactions with substrates, cofactors, or binding partners using isothermal titration calorimetry or surface plasmon resonance

- Specificity profiling: Screen against alternative substrates or targets to identify altered specificity

Physiological Assays

- Animal models: Express GOF variants in model organisms (mice, zebrafish) to assess organism-level effects

- Electrophysiology: For channelopathies, measure ionic currents and gating properties using patch clamp techniques

- High-throughput screening: Implement functional assays in multi-well format for systematic GOF variant characterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Mechanism Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2 models, FoldX | Predict protein structures and stability effects | All mechanisms [25] |

| Stability Assays | Thermal shift dyes (SYPRO Orange), Urea/GdnHCl | Experimental stability measurement | LOF, DN discrimination [21] |

| Interaction Mapping | Co-IP antibodies, FRET pairs, SPR chips | Protein-protein interaction analysis | DN mechanism validation [21] |

| Computational Tools | LoGoFunc, mLOF score, CADD, REVEL | Computational variant effect prediction | Mechanism classification [23] [25] |

| Expression Systems | Mammalian (HEK293), Bacterial (E. coli) | Recombinant protein production | Functional characterization |

| Variant Libraries | Saturation mutagenesis, Patient-derived variants | Functional screening | Mechanism-pathotype correlation |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The molecular mechanism of pathogenic variants directly informs therapeutic strategy development. LOF disorders are often amenable to gene replacement therapies or approaches that boost residual protein function [23]. In contrast, GOF and DN disorders typically require inhibitory approaches such as small-molecule inhibitors, targeted degradation, or allele-specific silencing [23].

The presence of intragenic mechanistic heterogeneity - where different mutations in the same gene cause disease through distinct mechanisms - presents both challenges and opportunities for precision medicine [23]. In such genes, therapeutic approaches must be tailored to the specific mechanism of each patient's mutation rather than applying a uniform treatment strategy.

Future research directions include:

- Developing improved computational methods that integrate structural, evolutionary, and functional data

- Expanding high-throughput experimental characterization of variant effects

- Creating mechanism-specific therapeutic platforms targeting shared pathological features

- Advancing allele-specific interventions that selectively target mutant alleles while sparing wild-type function

As our understanding of molecular mechanisms deepens and therapeutic technologies advance, mechanism-based treatment strategies will increasingly enable personalized approaches to genetic disorders.

The analysis of family pedigrees remains a cornerstone of clinical genetics, providing critical insights into the transmission of hereditary disorders. Understanding whether a condition follows an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive pattern is fundamental to estimating recurrence risks, guiding molecular testing, and informing drug development strategies. This framework originates from Mendelian inheritance principles, which describe how genetic traits are passed through generations via autosomes—the 22 paired chromosomes not involved in sex determination [13]. Autosomal inheritance patterns explain how genetic variants in single genes cause disorders, distinct from polygenic or chromosomal conditions [18].

Pedigree analysis enables researchers to determine the mode of inheritance by identifying characteristic patterns within family trees. This analysis forms the basis for genetic counseling, risk assessment, and the development of targeted genetic therapies. For pharmaceutical researchers, recognizing these patterns aids in identifying patient populations for clinical trials and understanding potential hereditary responses to therapeutics. This technical guide examines the defining characteristics, methodologies, and research applications of autosomal dominant and recessive pedigree analysis within the broader context of inheritance pattern research.

Fundamental Genetic Concepts and Definitions

Mendelian Inheritance Principles

Mendelian genetics provides the theoretical foundation for pedigree analysis, based on Gregor Mendel's three fundamental laws [2]. The Law of Segregation states that each individual possesses two alleles for a trait, which separate during gamete formation so each gamete carries only one allele. The Law of Independent Assortment describes how genes for different traits segregate independently during gamete formation. The Law of Dominance establishes that some alleles are dominant over others, with dominant traits expressed when at least one dominant allele is present [15].

Key Terminology in Pedigree Analysis

- Proband: The first family member identified with the disorder of interest; the index case that initiates pedigree construction [26]

- Autosomal Dominant: Inheritance pattern where a single copy of a mutant allele is sufficient to cause the disorder [2]

- Autosomal Recessive: Inheritance pattern requiring two copies of a mutant allele for the disorder to manifest [15]

- Penetrance: The proportion of individuals with a disease-causing variant who exhibit clinical symptoms [2]

- Consanguinity: Genetic relatedness between individuals who share recent common ancestors, increasing risk for recessive disorders [15]

- Carrier: An individual with one copy of a recessive mutant allele who typically does not show disease symptoms [27]

Autosomal Dominant Inheritance Patterns

Characteristic Pedigree Features

Autosomal dominant disorders display distinctive pedigree patterns that reflect their inheritance mechanism. Affected individuals typically have at least one affected parent, and the disorder appears in multiple generations without skipping [2]. This creates vertical transmission patterns where the trait can be traced through multiple vertical lines in the pedigree [15]. Males and females are equally likely to be affected and to transmit the disorder, with approximately 50% of offspring at risk when one parent is affected [2]. Affected family members are typically heterozygous for the dominant mutant allele [28].

Two exceptions to these patterns include de novo mutations, where a disorder appears in an individual with no family history, and reduced penetrance, where an individual inherits the mutant allele but does not express the disorder phenotype [2]. Age-dependent penetrance may also obscure inheritance patterns in disorders that manifest later in life.

Molecular Mechanisms and Genotype Correlations

In autosomal dominant disorders, the disease phenotype manifests despite the presence of one normal allele. Molecular mechanisms include haploinsufficiency (where a single functional copy does not produce sufficient protein), dominant-negative effects (where mutant protein disrupts function of normal protein), and gain-of-function mutations (where mutant protein acquires new toxic functions) [2].

Table 1: Characteristic Features of Autosomal Dominant Inheritance

| Feature | Description | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Pattern | Vertical, appears in multiple generations | Enables tracking through large pedigrees for gene mapping |

| Parent-Offspring | Affected individual has 50% chance of passing to offspring | Consistent recurrence risk simplifies genetic counseling |

| Sex Distribution | Males and females equally affected | No sex-linked modifiers expected in purely autosomal pattern |

| Sporadic Cases | Can occur due to de novo mutations | Complicates diagnosis; requires molecular confirmation |

Clinical and Research Examples

Marfan syndrome exemplifies autosomal dominant inheritance, resulting from mutations in the FBN1 gene on chromosome 15 encoding fibrillin-1 [2]. The disorder affects approximately 1 in 5,000-10,000 individuals worldwide without ethnic, geographic, or social class predilection. Clinical manifestations involve the skeletal, ocular, and cardiovascular systems, with cystic medial necrosis of the aorta representing the most life-threatening complication.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) demonstrates another autosomal dominant pattern, with about 30% of cases inherited and 70% resulting from de novo mutations [2]. TSC results from loss-of-function mutations in either TSC1 (encoding hamartin) or TSC2 (encoding tuberin), leading to dysregulated mTOR signaling and clinical manifestations including facial angiofibromas, renal angiomyolipomas, and neurological symptoms.

Autosomal Recessive Inheritance Patterns

Characteristic Pedigree Features

Autosomal recessive disorders exhibit fundamentally different pedigree patterns from dominant conditions. Typically, affected individuals are usually siblings within a single generation, with unaffected parents who are often carriers [15]. This creates a horizontal transmission pattern where multiple affected individuals appear in the same generation but not necessarily in previous or subsequent generations [15]. Consanguinity significantly increases the risk for autosomal recessive disorders, as related parents are more likely to carry the same recessive mutation [15] [29].

Autosomal recessive conditions can manifest through either homozygosity (two identical mutant alleles) or compound heterozygosity (two different mutant alleles in the same gene) [27]. Carrier parents have a 25% chance with each pregnancy of having an affected child, a 50% chance of having an asymptomatic carrier, and a 25% chance of having a child with two normal alleles [15] [27].

Molecular Mechanisms and Genotype Correlations

In autosomal recessive disorders, both alleles must be mutated for the disease to manifest. Molecular mechanisms typically involve loss-of-function mutations that eliminate or significantly reduce protein activity. Carriers with one functional allele are usually asymptomatic because the single normal allele produces sufficient protein for normal function, a phenomenon known as haplosufficiency [15].

Table 2: Characteristic Features of Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

| Feature | Description | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Pattern | Horizontal, often limited to single generation | May require extended family screening to identify patterns |

| Parent-Offspring | Two carrier parents have 25% affected offspring | Risk calculation constant for each pregnancy |

| Consanguinity | Increases recurrence risk | Important consideration in genetic counseling |

| Carrier Frequency | Varies by population and disorder | Impacts screening strategy design |

Clinical and Research Examples

Cystic fibrosis (CF) represents one of the most common autosomal recessive disorders in Caucasian populations, affecting approximately 1 in 1,000 births with a carrier frequency of 1 in 30 [15]. CF results from mutations in the CFTR gene on chromosome 7, which encodes a chloride channel protein. The most common mutation, p.Phe508del, accounts for approximately 72% of CF alleles in Caucasian populations but shows significant geographic variation [29].

Sickle cell disease demonstrates how autosomal recessive disorders can provide heterozygote advantage in specific environments. The disorder results from mutations in HBB encoding hemoglobin, with the p.Glu6Val mutation causing sickling of red blood cells under low oxygen conditions [15]. Carriers (with sickle cell trait) have protection against severe malaria, explaining the high allele frequency in malaria-endemic regions [15]. Carrier frequency for the p.Glu6Val mutation exceeds 30% in some African populations, compared to near absence in East Asian populations [29].

Tay-Sachs disease illustrates the profound impact of population-specific founder effects on autosomal recessive disorder prevalence. This neurodegenerative disorder results from HEXA gene mutations, with carrier frequency approximately 10 times higher in Ashkenazi Jewish populations (1 in 27) compared to other populations [15] [29].

Pedigree Analysis Methodologies

Standardized Pedigree Construction Protocols

Accurate pedigree analysis requires standardized symbols and notation to ensure consistent interpretation across research and clinical settings. The established protocol specifies circles for females, squares for males, and diamonds for unspecified gender [26]. Shaded symbols indicate affected individuals, while clear symbols represent unaffected individuals [28]. A horizontal line connecting two individuals represents mating, with vertical lines extending to their offspring [26]. Siblings should be drawn from left to right in birth order [26].

The proband (index case) should be clearly marked with an arrow, and each symbol should be labeled with current age or age at death, known diagnoses with age of onset, and relevant clinical information [26]. For research purposes, additional information including residence, ethnicity, and willingness to participate in research should be documented [26].

Diagnostic Algorithm for Inheritance Pattern Determination

The pedigree analysis algorithm begins with comprehensive family history collection, followed by systematic pattern recognition. Key decision points include assessing whether affected individuals appear in multiple generations (suggesting dominant inheritance) or primarily in a single generation (suggesting recessive inheritance) [15] [2]. Additional considerations include evaluating for male-to-male transmission (which excludes X-linked inheritance), assessing parental consanguinity, and determining sex distribution of affected individuals [28].

Advanced Analytical Techniques

Modern pedigree analysis incorporates computational tools for complex scenarios. Linkage analysis uses pedigree data to map disease genes by tracking co-segregation of genetic markers and disease phenotypes. Risk calculation algorithms incorporate Bayesian methods to integrate pedigree information with genetic test results. Population-adjusted genetic screening panels leverage ethnogeographic variant frequency data to optimize carrier detection rates [29].

Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pedigree Analysis and Genetic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Exome Sequencing Kits | Identification of coding variants in affected individuals | Coverage: >95% of exonic regions; Depth: >100x for heterozygote detection |

| SNP Microarrays | Genotype analysis for linkage studies and homozygosity mapping | Density: 1-4 million markers; Includes disease-relevant variants |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Validation of putative pathogenic variants identified by NGS | Accuracy: >99.99%; Capable of detecting mosaicism at >20% variant allele frequency |

| Cell Culture Media for Fibroblasts | Establishment of cell lines from affected individuals for functional studies | Supports growth of primary human fibroblasts; Serum-free options available |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Systems | Functional validation of putative pathogenic variants | Knock-in efficiency optimized for human cell lines; Includes controls |

| Population-Specific Genotype Panels | Carrier screening adjusted for ethnogeographic background | Includes founder mutations specific to target population [29] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Annotation and prioritization of sequence variants | Integrates population frequency, prediction algorithms, and clinical databases |

Population Genetics and Epidemiological Considerations

Global Distribution of Autosomal Recessive Disorders

Autosomal recessive disorders demonstrate striking population-specific differences in prevalence and genetic heterogeneity. Recent analysis of 508 genes associated with 450 AR disorders across 141,456 individuals from seven ethnogeographic groups revealed that 27% of AR diseases are limited to specific populations, while 68% show more than tenfold prevalence differences across major population groups [29]. These differences result from a combination of founder effects, genetic drift, and in some cases, heterozygote advantage.

Carrier frequencies for common autosomal recessive disorders vary dramatically between populations. For example, cystic fibrosis carrier frequency for the p.Phe508del mutation is 1 in 40 in European populations but nearly absent in East Asian populations [29]. Similarly, the HFE p.Cys282Tyr mutation causing hereditary hemochromatosis shows 300-fold higher carrier frequency in Europeans (1 in 9) compared to East Asians (1 in 3,000) [29].

Founder Effects and Population Genetics

Founder effects occur when a population originates from a small group of ancestors, some of whom carried specific genetic variants. This phenomenon explains the high frequency of certain autosomal recessive disorders in specific populations. For example, Ashkenazi Jewish populations show elevated frequencies of Tay-Sachs disease (HEXA mutations), Gaucher disease (GBA mutations), and Canavan disease (ASPA mutations) due to founder effects [29]. Similarly, the p.Trp1282Ter CFTR mutation accounts for 46% of cystic fibrosis cases in Ashkenazi Jews compared to only 1.5% in Europeans [29].

Molecular Genetic Complexity

The genetic complexity of autosomal recessive disorders varies significantly between conditions. Some disorders, like Stargardt disease (ABCA4) and sucrase-isomaltase deficiency (SI), demonstrate extreme genetic heterogeneity with hundreds of pathogenic variants [29]. Other disorders show concentration in specific pathogenic variants, enabling more targeted genetic screening approaches. This complexity has direct implications for genetic test design, as standardized panels that don't consider population differences may perform poorly in populations with specific founder mutations [29].

Research Applications and Drug Development Implications

Patient Stratification for Clinical Trials

Accurate pedigree analysis and inheritance pattern determination enable precise patient stratification for clinical trials. Understanding whether a condition follows autosomal dominant or recessive inheritance helps identify candidate populations for gene-based therapies. For clinical trials, pedigree analysis can identify extended family networks that may qualify for recruitment, particularly for rare genetic disorders.

Therapeutic Target Identification

Pedigree analysis facilitates the identification of novel therapeutic targets through the study of large families with multiple affected individuals. Linkage analysis in dominant families can narrow candidate regions, while homozygosity mapping in consanguineous recessive families can identify disease genes. Understanding inheritance patterns also informs therapeutic approaches—recessive disorders may benefit from gene replacement strategies, while dominant disorders may require gene silencing or correction approaches.

Pharmacogenomic Considerations