Beyond Significance: A Practical Guide to Equivalence Testing for Model Performance in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying equivalence tests to evaluate model performance.

Beyond Significance: A Practical Guide to Equivalence Testing for Model Performance in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying equivalence tests to evaluate model performance. Moving beyond traditional null-hypothesis significance testing, we explore the foundational concepts of equivalence testing, including the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure and the critical role of equivalence bounds. The methodological section delves into advanced approaches like model averaging to handle model uncertainty, while the troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls such as inflated Type I errors and strategies for power analysis. Finally, we cover validation frameworks aligned with emerging regulatory standards like ICH M15, offering a complete roadmap for demonstrating model comparability in biomedical research and regulatory submissions.

Why Equivalence? Moving Beyond Traditional Significance Testing

In model performance equivalence research, a common misconception is that a statistically non-significant result (p > 0.05) proves two models are equivalent. This article explains the logical fallacy behind this assumption and introduces equivalence testing as a statistically sound alternative for demonstrating similarity, complete with protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Fundamental Misinterpretation of Non-Significant Results

What p > 0.05 Actually Means

In standard null hypothesis significance testing (NHST), a p-value greater than 0.05 indicates that the observed data do not provide strong enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis, which typically states that no difference exists (e.g., no difference in model performance) [1] [2]. Critically, this outcome only tells us that we cannot reject the null hypothesis; it does not allow us to accept it or claim the effects are identical [3] [4].

The American Statistical Association (ASA) warns against misinterpreting p-values, stating, "Do not believe that an association or effect is absent just because it was not statistically significant" [4]. A non-significant p-value can result from several factors unrelated to true equivalence:

- High Variance: Noisy data can obscure real differences [1].

- Small Sample Size: Studies with insufficient power may fail to detect meaningful differences that actually exist [1] [5].

The Logical Fallacy: Absence of Evidence vs. Evidence of Absence

Interpreting p > 0.05 as proof of equivalence confuses absence of evidence for a difference with evidence of absence of a difference [3]. As one source notes, "A conclusion does not immediately become 'true' on one side of the divide and 'false' on the other" [4]. In model comparison, failing to prove models are different is not the same as proving they are equivalent.

Core Principles of Equivalence Testing

Equivalence testing directly addresses the need to demonstrate similarity by flipping the conventional testing logic. In equivalence testing:

- The null hypothesis (Hâ‚€) states that the difference between two models is meaningfully large (i.e., lies outside a pre-defined equivalence margin) [5] [6].

- The alternative hypothesis (Hâ‚) states that the difference is trivial (i.e., lies within the equivalence margin) [5].

Rejecting the null hypothesis in this framework provides direct statistical evidence for equivalence, a claim that NHST cannot support [6].

Defining the Equivalence Region

The cornerstone of a valid equivalence test is the equivalence region (also called the "region of practical equivalence" or "smallest effect size of interest") [3] [5]. This is a pre-specified range of values within which differences are considered practically meaningless. The bounds of this region (ΔL and ΔU) should be justified based on:

- Clinical or practical relevance [5] [7]

- Domain expertise and prior knowledge [7]

- Risk assessment (e.g., high-risk scenarios require narrower margins) [7]

For example, in bioequivalence studies for generic drugs, a common equivalence margin is 20%, leading to an acceptance range of 0.80 to 1.25 for the ratio of geometric means [8].

Key Methodological Approaches and Protocols

The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) Procedure

The most common method for equivalence testing is the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure [3] [5] [8]. This approach tests whether the observed difference is simultaneously greater than the lower equivalence bound and smaller than the upper equivalence bound.

Experimental Protocol: TOST Procedure

- Pre-specify Equivalence Margin: Define ΔL (lower bound) and ΔU (upper bound) based on practical significance before data collection [5] [7].

- Calculate Test Statistics: Perform two one-sided t-tests:

- Test 1: TL = (M₠- M₂ - ΔL) / (SE)

- Test 2: TU = (M₠- M₂ - ΔU) / (SE) where M₠and M₂ are group means, and SE is the standard error [3].

- Evaluate Significance: If both tests yield p-values < 0.05, reject the null hypothesis of non-equivalence and conclude equivalence [5] [8].

- Confirm with Confidence Intervals: The 90% confidence interval for the difference should lie entirely within the equivalence bounds [5] [8].

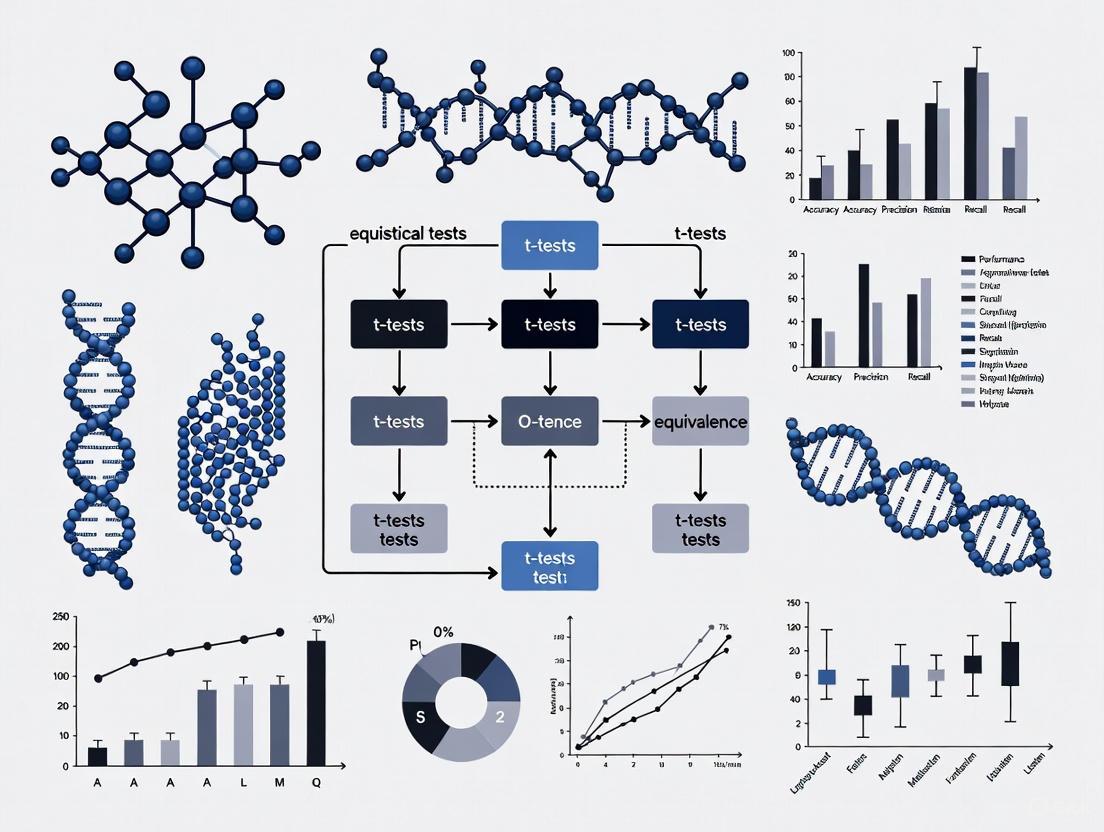

The following diagram illustrates the TOST procedure logic and decision criteria:

Confidence Interval Approach

An alternative but complementary view uses confidence intervals:

- Calculate a 90% confidence interval for the difference between measures [5]

- If the entire confidence interval falls within the pre-specified equivalence bounds, equivalence is demonstrated at the 5% significance level [5]

This approach is visually intuitive and provides additional information about the precision of the estimate.

Practical Applications and Experimental Design

Applications in Model Performance Research

Equivalence testing is particularly valuable in several research scenarios:

- Method Comparison Studies: Demonstrating that a new, cheaper, or faster model performs equivalently to an established gold standard [5]

- Replication Studies: Testing whether a new study replicates a previous finding by showing effects are equivalent within a reasonable margin [3]

- Reliability Assessments: Establishing test-retest reliability by showing measurements taken at different times are equivalent [6]

Regulatory and Industry Applications

In pharmaceutical development and regulatory science, equivalence testing is well-established:

- Bioequivalence Studies: Generic drugs must demonstrate equivalent pharmacokinetic parameters to brand-name drugs [8]

- Biosimilarity Assessment: Biological products must show they are highly similar to reference products despite minor differences [8]

- Process Change Validation: Manufacturing process changes require demonstration of equivalent product quality attributes [7]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines key methodological components for implementing equivalence testing in research practice:

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Equivalence Margin | Defines the range of practically insignificant differences | Pre-specified as ±Δ based on clinical relevance or effect size conventions [5] |

| TOST Framework | Provides statistical test for equivalence | Two one-sided t-tests with null hypotheses of non-equivalence [3] [8] |

| Power Analysis | Determines sample size needed to detect equivalence | Sample size calculation ensuring high probability of rejecting non-equivalence when true difference is small [7] |

| Confidence Intervals | Visual and statistical assessment of equivalence | 90% CI plotted with equivalence bounds; complete inclusion demonstrates equivalence [5] |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Tests robustness of conclusions to margin choices | Repeating analysis with different equivalence margins to ensure conclusions are consistent [5] |

Complete Experimental Workflow for Equivalence Testing

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow for designing, executing, and interpreting an equivalence study:

The misinterpretation of p > 0.05 as proof of equivalence represents a significant logical and statistical error in model performance research. Equivalence testing, particularly through the TOST procedure, provides a rigorous methodological framework for demonstrating similarity when that is the research objective. By pre-specifying clinically meaningful equivalence bounds and using appropriate statistical techniques, researchers can make valid claims about equivalence that stand up to scientific and regulatory scrutiny.

In statistical hypothesis testing, particularly in equivalence and non-inferiority research, the Smallest Effect Size of Interest (SESOI) represents the threshold below which effect sizes are considered practically or clinically irrelevant. Unlike traditional significance testing that examines whether an effect exists, equivalence testing investigates whether an effect is small enough to be considered negligible for practical purposes. The SESOI is formalized through predetermined equivalence bounds (denoted as Δ or -ΔL to ΔU), which create a range of values considered practically equivalent to the null effect. Establishing appropriate equivalence bounds enables researchers to statistically reject the presence of effects substantial enough to be meaningful, thus providing evidential support for the absence of practically important effects [9].

The specification of SESOI marks a paradigm shift from merely testing whether effects are statistically different from zero to assessing whether they are practically insignificant. This approach addresses a critical limitation of traditional null hypothesis significance testing, where non-significant results (p > α) are often misinterpreted as evidence for no effect, when in reality the test might simply lack statistical power to detect a true effect [9] [3]. Within the frequentist framework, the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure has emerged as the most widely recommended method for testing equivalence, where an upper and lower equivalence bound is specified based on the SESOI [9].

Theoretical Foundations and Statistical Framework

The TOST Procedure and Interval Hypotheses

The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure, developed in pharmaceutical sciences and later formalized for broader applications, provides a straightforward method for equivalence testing [9] [3]. In this procedure, two composite null hypotheses are tested: H01: Δ ≤ -ΔL and H02: Δ ≥ ΔU, where Δ represents the true effect size. Rejecting both null hypotheses allows researchers to conclude that -ΔL < Δ < ΔU, meaning the observed effect falls within the equivalence bounds and is practically equivalent to the null effect [9].

The TOST procedure fundamentally changes the structure of hypothesis testing from point null hypotheses to interval hypotheses. Rather than testing against a nil null hypothesis of exactly zero effect, equivalence tests evaluate non-nil null hypotheses that represent ranges of effect sizes deemed importantly different from zero [3]. This approach aligns statistical testing more closely with scientific reasoning, as researchers are typically interested in rejecting effect sizes large enough to be meaningful rather than proving effects exactly equal to zero [9] [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Testing Approaches

| Testing Approach | Null Hypothesis | Alternative Hypothesis | Scientific Question | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional NHST | Effect = 0 | Effect ≠0 | Is there any effect? | ||||

| Equivalence Test | Effect | ≥ Δ | Effect | < Δ | Is the effect negligible? | ||

| Minimum Effect Test | Effect | ≤ Δ | Effect | > Δ | Is the effect meaningful? |

Interpreting Results from Equivalence Tests

When combining traditional null hypothesis significance tests (NHST) with equivalence tests, four distinct interpretations emerge from study results [9]:

- Statistically equivalent and not statistically different from zero: The 90% confidence interval around the observed effect excludes the equivalence bounds, while the 95% confidence interval includes zero.

- Statistically different from zero but not statistically equivalent: The 95% confidence interval excludes zero, but the 90% confidence interval includes at least one equivalence bound.

- Statistically different from zero and statistically equivalent: Both the 90% confidence interval excludes the equivalence bounds and the 95% confidence interval excludes zero.

- Undetermined: Neither statistically different from zero nor statistically equivalent.

This refined classification enables more nuanced statistical conclusions than traditional dichotomous significant/non-significant outcomes.

Practical Approaches for Setting Equivalence Bounds

Methodological Frameworks for Determining SESOI

Establishing appropriate equivalence bounds requires careful consideration of contextual factors. Several established approaches guide researchers in determining the SESOI [9]:

- Clinical or practical significance: In medical research, bounds may be based on the Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID), representing the smallest difference patients or clinicians would consider important [10].

- Theoretical predictions: When theories make precise predictions about effect sizes, bounds can be set based on theoretically meaningful thresholds.

- Resource constraints: When theoretical or practical boundaries are absent, researchers may set bounds based on the smallest effect size they have sufficient power to detect given available resources [9].

- Field-specific conventions: Some domains have established standards, such as the 80%-125% bioequivalence criterion used in pharmaceutical research [11] [12].

The equivalence bound can be symmetric around zero (e.g., ΔL = -0.3 to ΔU = 0.3) or asymmetric (e.g., ΔL = -0.2 to ΔU = 0.4), depending on the research context and consequences of positive versus negative effects [9].

Standardized Effect Size Benchmarks

For psychological and social sciences where raw effect sizes lack intuitive interpretation, setting bounds based on standardized effect sizes (e.g., Cohen's d, η²) facilitates comparison across studies using different measures [9]. Common benchmarks include:

Table 2: Common Standardized Effect Size Benchmarks for Equivalence Bounds

| Effect Size Metric | Small Effect | Medium Effect | Large Effect | Typical Equivalence Bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen's d | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | ±0.2 to ±0.5 |

| Correlation (r) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ±0.1 to ±0.2 |

| Partial η² | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.01 to 0.04 |

For ANOVA models, equivalence bounds can be set using partial eta-squared (η²p) values, representing the proportion of variance explained. Campbell and Lakens (2021) recommend setting bounds based on the smallest proportion of variance that would be considered theoretically or practically meaningful [13].

Regulatory and Domain-Specific Standards

In pharmaceutical research and bioequivalence studies, stringent standards have been established through regulatory guidance. The 80%-125% rule is widely accepted for bioequivalence assessment, based on the assumption that differences in systemic exposure smaller than 20% are not clinically significant [11] [12]. This criterion requires that the 90% confidence intervals of the ratios of geometric means for pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC and Cmax) fall entirely within the 80%-125% range after logarithmic transformation [11].

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index or high intra-subject variability, regulatory agencies may require stricter equivalence bounds or specialized statistical approaches such as reference-scaled average bioequivalence with replicated crossover designs [11]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) emphasizes that equivalence margins should be justified through a combination of empirical evidence and clinical judgment, considering the smallest difference that would warrant disregarding a novel intervention in favor of a criterion standard [10] [14].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

The TOST Procedure: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Implementing equivalence testing using the TOST procedure involves these methodical steps [9] [3]:

Define equivalence bounds: Before data collection, specify lower and upper equivalence bounds (-ΔL and ΔU) based on the SESOI, considering clinical, theoretical, or practical implications.

Collect data and compute test statistics: Conduct the study using appropriate experimental designs (e.g., crossover, parallel groups) with sufficient sample size determined through power analysis.

Perform two one-sided tests:

- Test H01: Δ ≤ -ΔL using t-statistic:

- Test H02: Δ ≥ ΔU using t-statistic: Where M1 and M2 are group means, and SE is the standard error of the difference.

Evaluate p-values: Obtain p-values for both one-sided tests. If both p-values are less than the chosen α level (typically 0.05), reject the composite null hypothesis of meaningful effect.

Interpret confidence intervals: Alternatively, construct a 90% confidence interval for the effect size. If this interval falls completely within the equivalence bounds (-ΔL to ΔU), conclude equivalence.

Figure 1: TOST Procedure Workflow for Equivalence Testing

Sample Size Planning and Power Analysis

Power analysis for equivalence tests requires special consideration, as standard power calculations for traditional tests are inadequate. When planning equivalence studies, researchers should [9]:

- Conduct power analyses specifically designed for equivalence tests

- Determine sample size needed to reject both null hypotheses when the true effect is zero

- Consider that equivalence tests generally require larger sample sizes than traditional tests to achieve comparable power

- Account for the specified equivalence bounds in power calculations, with narrower bounds requiring larger samples

For F-test equivalence testing in ANOVA designs, power analysis involves calculating the non-centrality parameter based on the equivalence bound and degrees of freedom [13]. The TOSTER package in R provides specialized functions for power analysis of equivalence tests, enabling researchers to determine required sample sizes for various designs [13].

Regulatory Considerations for Clinical Trials

In clinical trial design, particularly for non-inferiority and equivalence trials, the estimands framework (ICH E9[R1]) provides a structured approach to defining treatment effects [14]. Key considerations include:

- Handling intercurrent events: Post-baseline events that affect endpoint interpretation (e.g., treatment discontinuation) must be addressed using appropriate strategies (treatment policy, hypothetical, composite, etc.)

- Dual estimand approach: Regulatory agencies often recommend defining two co-primary estimands using different strategies for handling intercurrent events [14]

- Maintaining blinding: Equivalence trials should maintain blinding to prevent biased assessment of endpoints

- Prespecification: All aspects of equivalence testing, including bounds, analysis methods, and handling of intercurrent events, must be specified before data collection

Comparison of Equivalence Testing Approaches

Domain-Specific Applications and Standards

Equivalence testing methodologies vary across research domains, reflecting differing needs and regulatory requirements:

Table 3: Comparison of Equivalence Testing Approaches Across Domains

| Research Domain | Primary Metrics | Typical Equivalence Bounds | Regulatory Guidance | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacokinetics/Bioequivalence | AUC, Cmax ratios | 80%-125% (log-transformed) | FDA, EMA, ICH guidelines | Narrow therapeutic index drugs require stricter bounds |

| Clinical Trials (Non-inferiority) | Clinical endpoints | Based on MCID and prior superiority effects | EMA, FDA guidance | Choice of estimand for intercurrent events critical |

| Psychology/Social Sciences | Standardized effect sizes (Cohen's d, η²) | ±0.2 to ±0.5 SD units | APA recommendations | Often lack consensus on meaningful effect sizes |

| Manufacturing/Quality Control | Process parameters | Based on functional specifications | ISO standards | Often one-sided equivalence testing |

Advanced Methodological Variations

Beyond the standard TOST procedure, several advanced equivalence testing methods have been developed:

- Non-inferiority tests: One-sided tests examining whether an intervention is not substantially worse than a comparator [10]

- Minimum effect tests: Tests that reject effect sizes smaller than a specified minimum value, establishing that an effect is both statistically and practically significant [3]

- Empirical Equivalence Bound (EEB): A data-driven approach that estimates the minimum equivalence bound that would lead to equivalence when equivalence is true [15]

- Bayesian equivalence methods: Approaches that use Bayesian statistics to evaluate evidence for equivalence

For ANOVA models, equivalence testing can be extended to omnibus F-tests using the non-central F distribution. The test evaluates whether the total proportion of variance attributable to factors is less than the equivalence bound [13].

Statistical Software and Implementation Tools

Several specialized tools facilitate implementation of equivalence tests:

Table 4: Essential Resources for Equivalence Testing

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOSTER Package | Equivalence tests for t-tests, correlations, meta-analyses | R, SPSS, Spreadsheet | User-friendly interface, power analysis |

| equ_ftest() Function | Equivalence testing for F-tests in ANOVA | R (TOSTER package) | Handles various ANOVA designs, power calculation |

| B-value Calculation | Empirical equivalence bound estimation | Custom R code | Data-driven bound estimation |

| Power Analysis Tools | Sample size determination for equivalence tests | R (TOSTER), PASS, G*Power | Specialized for equivalence testing needs |

| Regulatory Guidance Documents | Protocol requirements for clinical trials | FDA, EMA websites | Domain-specific standards and requirements |

Reporting Guidelines and Best Practices

When reporting equivalence tests, researchers should:

- Clearly justify the chosen equivalence bounds based on clinical, theoretical, or practical considerations

- Report both traditional significance tests and equivalence test results

- Include confidence intervals alongside point estimates

- Document power calculations and sample size justifications

- For clinical trials, specify estimands and strategies for handling intercurrent events

- Use appropriate visualizations to display equivalence test results

Figure 2: Interpreting Equivalence Test Results Using Confidence Intervals

Setting appropriate equivalence bounds based on the Smallest Effect Size of Interest represents a fundamental advancement in statistical practice, enabling researchers to draw meaningful conclusions about the absence of practically important effects. The TOST procedure provides a statistically sound framework for implementing equivalence tests across diverse research domains, from pharmaceutical development to social sciences. By carefully considering clinical, theoretical, and practical implications when establishing equivalence bounds, and following rigorous experimental protocols, researchers can produce more informative and clinically relevant results. As methodological developments continue to emerge, including empirical equivalence bounds and Bayesian approaches, the statistical toolkit for equivalence testing will further expand, enhancing our ability to demonstrate when differences are negligible enough to be disregarded for practical purposes.

In scientific research, particularly in fields like drug development and psychology, researchers often need to demonstrate the absence of a meaningful effect rather than confirm its presence. Equivalence testing provides a statistical framework for this purpose, reversing the traditional logic of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST). While NHST aims to reject the null hypothesis of no effect, equivalence testing allows researchers to statistically reject the presence of effects large enough to be considered meaningful, thereby providing support for the absence of a practically significant effect [9].

This comparative guide examines the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure, the most widely recommended approach for equivalence testing within a frequentist framework. We will explore its statistical foundations, compare it with traditional significance testing, provide detailed experimental protocols, and demonstrate its application across various research contexts, with particular emphasis on pharmaceutical development and model performance evaluation.

TOST Procedure: Core Concepts and Statistical Framework

Foundational Principles

The TOST procedure operates on a different logical framework than traditional hypothesis tests. Instead of testing against a point null hypothesis (e.g., μ₠- μ₂ = 0), TOST evaluates whether the true effect size falls within a predetermined range of practically equivalent values [9] [16].

The procedure establishes an equivalence interval defined by lower and upper bounds (ΔL and ΔU) representing the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI). These bounds specify the range of effect sizes considered practically insignificant, often symmetric around zero (e.g., -0.3 to 0.3 for Cohen's d) but potentially asymmetric in applications where risks differ in each direction [9] [7].

The statistical hypotheses for TOST are formulated as:

- Null hypothesis (H₀): The true effect is outside the equivalence bounds (Δ ≤ -ΔL or Δ ≥ ΔU)

- Alternative hypothesis (Hâ‚): The true effect is within the equivalence bounds (-ΔL < Δ < ΔU) [9] [16]

Operational Mechanism

TOST decomposes the composite null hypothesis into two one-sided tests conducted simultaneously:

- Test 1: H₀¹: Δ ≤ -ΔL versus H₹: Δ > -ΔL

- Test 2: H₀²: Δ ≥ ΔU versus H₲: Δ < ΔU [16]

Equivalence is established only if both one-sided tests reject their respective null hypotheses at the chosen significance level (typically α = 0.05 for each test) [9]. This dual requirement provides strong control over Type I error rates, ensuring the probability of falsely claiming equivalence does not exceed α [16].

Table 1: Key Components of the TOST Procedure

| Component | Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Equivalence Bounds | Pre-specified range (-ΔL to ΔU) of practically insignificant effects | Should be justified based on theoretical, clinical, or practical considerations [9] |

| Two One-Sided Tests | Simultaneous tests against lower and upper bounds | Each test conducted at significance level α (typically 0.05) [16] |

| Confidence Interval | 100(1-2α)% confidence interval (e.g., 90% CI when α=0.05) | Equivalence concluded if entire CI falls within equivalence bounds [9] [17] |

| Decision Rule | Reject non-equivalence if both one-sided tests are significant | Provides strong control of Type I error at α [16] |

TOST Versus Traditional Significance Testing

Conceptual and Practical Differences

TOST and traditional NHST address fundamentally different research questions, leading to distinct interpretations and conclusions, particularly in cases of non-significant results.

Table 2: Comparison Between Traditional NHST and TOST Procedure

| Aspect | Traditional NHST | TOST Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Research Question | Is there a statistically significant effect? | Is the effect practically insignificant? |

| Null Hypothesis | Effect size equals zero | Effect size exceeds equivalence bounds |

| Alternative Hypothesis | Effect size does not equal zero | Effect size falls within equivalence bounds |

| Interpretation of p > α | Inconclusive ("no evidence of an effect") | Cannot claim equivalence [9] |

| Type I Error | Concluding an effect exists when it doesn't | Concluding equivalence when effects are meaningful [18] |

| Confidence Intervals | 95% CI; significance if excludes zero | 90% CI; equivalence if within bounds [9] [17] |

Interpreting Different Outcomes

The relationship between TOST and NHST leads to four possible conclusions in research findings [9]:

- Statistically equivalent and not statistically different from zero: The 90% CI falls entirely within equivalence bounds, and the 95% CI includes zero

- Statistically different from zero but not statistically equivalent: The 95% CI excludes zero, but the 90% CI exceeds equivalence bounds

- Statistically different from zero and statistically equivalent: The 90% CI falls within bounds, and the 95% CI excludes zero (possible with high precision)

- Undetermined: Neither statistically different from zero nor statistically equivalent

This nuanced interpretation framework prevents the common misinterpretation of non-significant NHST results as evidence for no effect [9].

Establishing Equivalence Bounds and Experimental Protocols

Determining the Smallest Effect Size of Interest

Setting appropriate equivalence bounds represents one of the most critical aspects of TOST implementation. Three primary approaches guide this process:

- Theoretical justification: Bounds based on established minimal important differences in the field

- Practical considerations: Bounds reflecting cost-benefit tradeoffs or risk assessments

- Resource-based approach: When theoretical boundaries are absent, bounds can be set to the smallest effect size researchers have sufficient power to detect given available resources [9]

In pharmaceutical applications, equivalence bounds often derive from risk-based assessments considering potential impacts on process capability and out-of-specification rates [7]. For instance, shifting a critical quality attribute by a certain percentage (e.g., 10-25%) may be evaluated for its impact on failure rates, with higher-risk attributes warranting narrower bounds [7].

Statistical Implementation Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol outlines the TOST procedure for comparing a test product to a standard reference, a common application in pharmaceutical development [7]:

Step 1: Define Equivalence Bounds

- Identify the reference standard and its target value

- Conduct risk assessment to establish upper and lower practical limits (UPL and LPL)

- Justify bounds based on scientific knowledge, product experience, and clinical relevance

- Example: For pH with USL=8 and LSL=7, medium risk might justify bounds of ±0.15 (15% of tolerance) [7]

Step 2: Determine Sample Size

- Conduct power analysis to ensure adequate sensitivity

- Use formula for one-sided tests: n = (tâ‚₋α + tâ‚₋β)²(s/δ)²

- Account for the dual one-sided testing structure (α typically 0.05 for each test)

- Example: Minimum sample size of 13 with target of 15 for medium effect [7]

Step 3: Data Collection and Preparation

- Collect measurements according to predefined experimental design

- Calculate differences from standard reference value

- Verify data quality and assumptions

Step 4: Statistical Analysis

- Perform two one-sided t-tests against LPL and UPL

- Calculate p-values for both tests:

- pL = P(t ≥ (x̄ - LPL)/(s/√n))

- pU = P(t ≤ (x̄ - UPL)/(s/√n)) [7]

- Construct 90% confidence interval around mean difference

Step 5: Interpretation and Conclusion

- If both p-values < 0.05 (and 90% CI within bounds), conclude equivalence

- Report results with confidence intervals and justification for equivalence bounds

- If equivalence not demonstrated, conduct root-cause analysis [7]

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development and Model Evaluation

Bioequivalence and Comparability Studies

TOST has extensive applications in pharmaceutical development, particularly in bioequivalence trials where researchers aim to demonstrate that two drug formulations have similar pharmacokinetic properties [18]. Regulatory agencies like the FDA require 90% confidence intervals for geometric mean ratios of key parameters (e.g., AUC, Cmax) to fall within [0.8, 1.25] to establish bioequivalence [16].

In comparability studies following manufacturing process changes, TOST provides statistical evidence that product quality attributes remain equivalent pre- and post-change [7]. This application is crucial for regulatory submissions, as highlighted in FDA's guidance on comparability protocols [7].

Clinical Trial Applications

Equivalence trials in clinical research aim to show that a new intervention is not unacceptably different from a standard of care, potentially offering advantages in cost, toxicity, or administration [18]. For example:

- McCann et al. tested equivalence in neurodevelopment between anesthesia types, defining equivalence as ≤5 point difference in IQ scores [18]

- Marzocchi et al. established equivalence between tirofiban and abciximab with a 10% margin for ST-segment resolution [18]

These applications demonstrate how TOST facilitates evidence-based decisions about treatment alternatives while controlling error rates.

Implementation Tools and Visualization

Software and Computational Tools

While early adoption of equivalence testing in psychology was limited by software accessibility [9], dedicated packages now facilitate TOST implementation:

- R packages: The

TOSTERpackage provides comprehensive functions for t-tests, correlations, and meta-analyses [19] - Spreadsheet implementations: User-friendly calculators for common equivalence tests [9]

- Statistical software: Commercial packages like JMP and Minitab include equivalence testing modules

The t_TOST() function in R performs three tests simultaneously: the traditional two-tailed test and two one-sided equivalence tests, providing comprehensive results in a single operation [20].

Visual Representation of TOST Logic

The following diagram illustrates the decision framework for the TOST procedure, showing the relationship between confidence intervals and equivalence conclusions:

This decision framework illustrates how the combination of TOST and traditional testing leads to nuanced conclusions about equivalence and difference, addressing the limitation of traditional NHST in supporting claims of effect absence [9].

Table 3: Key Resources for Implementing Equivalence Tests

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R with TOSTER package [19] |

Comprehensive equivalence testing implementation |

| Sample Size Calculators | Power analysis tools for TOST [9] | Determining required sample size for target power |

| Equivalence Bound Justification | Risk assessment frameworks [7] | Establishing scientifically defensible bounds |

| Data Visualization | Consonance plots [20] | Visual representation of equivalence test results |

| Regulatory Guidance | FDA/EMA bioequivalence standards [16] | Defining equivalence criteria for specific applications |

The TOST procedure represents a fundamental advancement in statistical methodology, enabling researchers to make scientifically rigorous claims about effect absence rather than merely failing to detect differences. Its logical framework, based on simultaneous testing against upper and lower equivalence bounds, provides strong error control while addressing a question of profound practical importance across scientific disciplines.

For model performance evaluation and pharmaceutical development, TOST offers particular value in comparability assessments, bioequivalence studies, and method validation. By specifying smallest effect sizes of interest based on theoretical or practical considerations, researchers can design informative experiments that advance scientific knowledge beyond the limitations of traditional significance testing.

As methodological awareness increases and software implementation becomes more accessible, equivalence testing is poised to become an standard component of the statistical toolkit, promoting more nuanced and scientifically meaningful inference across research domains.

Bioequivalence (BE) assessment serves as a critical regulatory pathway for approving generic drug products, founded on the principle that demonstrating comparable drug exposure can serve as a surrogate for demonstrating comparable therapeutic effect [12]. According to the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR Part 320), bioavailability refers to "the extent and rate to which the active drug ingredient or active moiety from the drug product is absorbed and becomes available at the site of drug action" [21]. When two drug products are pharmaceutical equivalents or alternatives and their rates and extents of absorption show no significant differences, they are considered bioequivalent [12].

This concept forms the Foundation of generic drug approval under the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, which allows for Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) that do not require lengthy clinical trials for safety and efficacy [12]. The Fundamental Bioequivalence Assumption states that "if two drug products are shown to be bioequivalent, it is assumed that they will generally reach the same therapeutic effect or they are therapeutically equivalent" [12]. This regulatory framework has made cost-effective generic therapeutics widely available, typically priced 80-85% lower than their brand-name counterparts [11].

Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

FDA Statistical Approaches to Bioequivalence

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) 2001 guidance document "Statistical Approaches to Establishing Bioequivalence" provides recommendations for sponsors using equivalence criteria in analyzing in vivo or in vitro BE studies for Investigational New Drugs (INDs), New Drug Applications (NDAs), ANDAs, and supplements [22]. This guidance discusses three statistical approaches for comparing bioavailability measures: average bioequivalence, population bioequivalence, and individual bioequivalence [22].

The FDA's current regulatory framework requires pharmaceutical companies to establish that test and reference formulations are average bioequivalent, though distinctions exist between prescribability (where either formulation can be chosen for starting therapy) and switchability (where a patient can switch between formulations without issues) [23]. For regulatory approval, evidence of BE must be submitted in any ANDA, with certain exceptions where waivers may be granted [21].

Types of Bioequivalence Studies

Table 1: Approaches to Bioequivalence Assessment

| Approach | Definition | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|

| Average Bioequivalence (ABE) | Formulations are equivalent with respect to means of their probability distributions | Currently required by USFDA [23] |

| Population Bioequivalence (PBE) | Formulations equivalent with respect to underlying probability distributions | Discussed in FDA guidance [22] |

| Individual Bioequivalence (IBE) | Formulations equivalent for large proportion of individuals | Discussed in FDA guidance [22] |

ICH Guidelines and Global Harmonization

Substantial efforts for global harmonization of bioequivalence requirements have been undertaken through initiatives like the Global Bioequivalence Harmonization Initiative (GBHI) and the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) [11]. One significant development is the ICH M9 guideline, which addresses the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS)-based biowaiver concept, allowing waivers for in vivo bioequivalence studies under certain conditions based on drug solubility and permeability [11].

Harmonization efforts focus on several key areas, including selection criteria for reference products among regulatory agencies to reduce the need for repetitive BE studies, and requirements for waivers for BE studies [11]. These international harmonization initiatives aim to streamline global drug development while maintaining rigorous standards for therapeutic equivalence.

Statistical Foundations of Bioequivalence Testing

Hypothesis Testing in Equivalence Trials

Unlike superiority trials that aim to detect differences, equivalence trials test the null hypothesis that differences between treatments exceed a predefined margin [18]. The statistical formulation for average bioequivalence testing is structured as:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): μT/μR ≤ Ψ₠or μT/μR ≥ Ψ₂

- Alternative Hypothesis (Hâ‚): Ψ₠< μT/μR < Ψ₂

where μT and μR represent population means for test and reference formulations, and Ψ₠and Ψ₂ are equivalence margins set at 0.80 and 1.25, respectively, for pharmacokinetic parameters like AUC and Cmax [23].

The type 1 error (false positive) in equivalence trials is the risk of falsely concluding equivalence when treatments are actually not equivalent, typically set at 5% [18]. This means we need 95% confidence that the treatment difference does not exceed the equivalence margin in either direction.

Confidence Interval Approach

The standard analytical approach for bioequivalence assessment uses the confidence interval method [18]. For average bioequivalence, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means of the primary pharmacokinetic parameters must fall entirely within the bioequivalence limits of 80% to 125% [11]. This is typically implemented using:

- The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure, which employs two one-sided tests with 5% significance levels each, corresponding to a two-sided 90% confidence interval [18]

- Alternatively, a single two-sided test with 5% significance level, corresponding to a two-sided 95% confidence interval [18]

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for bioequivalence assessment using the confidence interval approach:

Figure 1: Bioequivalence Statistical Decision Pathway

Logarithmic Transformation

Pharmacokinetic parameters like AUC and Cmax typically follow lognormal distributions rather than normal distributions [23]. Applying logarithmic transformation achieves normal distribution of the data and creates symmetry in the equivalence criteria [11]. On the logarithmic scale, the bioequivalence range of 80-125% becomes -0.2231 to 0.2231, which is symmetric around zero [11]. After statistical analysis on the transformed data, results are back-transformed to the original scale for interpretation.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Standard Bioequivalence Study Designs

The FDA recommends crossover designs for bioavailability studies unless parallel or other designs are more appropriate for valid scientific reasons [12]. The most common experimental designs include:

- Two-period, two-sequence, two-treatment, single-dose crossover design: The most commonly used design where each subject receives both test and reference formulations in randomized sequence with adequate washout periods [11]

- Single-dose parallel design: Used when crossover designs are not feasible due to long half-lives or other considerations

- Replicate design: Employed for highly variable drugs or specific regulatory requirements, allowing estimation of within-subject variability [11]

For certain products intended for EMA submission, a multiple-dose crossover design may be used to assess steady-state conditions [11].

Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters

Table 2: Primary Pharmacokinetic Parameters in Bioequivalence Studies

| Parameter | Definition | Physiological Significance | BE Assessment Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC₀–t | Area under concentration-time curve from zero to last measurable time point | Measure of total drug exposure (extent of absorption) | Primary endpoint for extent of absorption [11] |

| AUC₀–∞ | Area under concentration-time curve from zero to infinity | Measure of total drug exposure accounting for complete elimination | Primary endpoint for extent of absorption [11] |

| Cmax | Maximum observed concentration | Measure of peak exposure (rate of absorption) | Primary endpoint for rate of absorption [11] |

| Tmax | Time to reach Cmax | Measure of absorption rate | Supportive parameter; differences may require additional analyses [11] |

Subject Selection and Ethical Considerations

BE studies are generally conducted in individuals at least 18 years old, who may be healthy volunteers or specific patient populations for which the drug is intended [11]. The use of healthy volunteers rather than patients is based on the assumption that bioequivalence in healthy subjects is predictive of therapeutic equivalence in patients [12]. Sample size determination considers the equivalence margin, type I error (typically 5%), and type II error (typically 80-90% power), with requirements generally larger than superiority trials due to the small equivalence margins [18].

Bioequivalence Criteria and Statistical Analysis

The 80-125% Rule

The current international standard for bioequivalence requires that the 90% confidence intervals for the ratio of geometric means of both AUC and Cmax must fall entirely within 80-125% limits [11]. This criterion was established based on the assumption that differences in systemic exposure smaller than 20% are not clinically significant [11]. The following diagram illustrates various possible outcomes when comparing confidence intervals to equivalence margins:

Figure 2: Confidence Interval Scenarios for Bioequivalence

Analysis of Variance in Crossover Designs

For standard 2x2 crossover studies, statistical analysis typically employs analysis of variance (ANOVA) models that account for sequence, period, and treatment effects [23]. The mixed-effects model includes:

- Fixed effects: Formulation, period, sequence

- Random effect: Subject within sequence

The FDA recommends logarithmic transformation of AUC and Cmax before analysis, with results back-transformed to the original scale for presentation [23]. Both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses should be presented, as intention-to-treat analysis may minimize differences and potentially lead to erroneous conclusions of equivalence [18].

Special Cases and Methodological Adaptations

Highly Variable Drugs

For drugs with high within-subject variability (intra-subject CV > 30%), standard bioequivalence criteria may require excessively large sample sizes [11]. Regulatory agencies have developed adapted approaches such as reference-scaled average bioequivalence that scale the equivalence limits based on within-subject variability of the reference product [11].

Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

For drugs with narrow therapeutic indices (e.g., warfarin, digoxin), where small changes in blood concentration can cause therapeutic failure or severe adverse events, stricter bioequivalence criteria have been proposed [11]. These may include tighter equivalence limits (e.g., 90-111%) or replicated study designs that allow comparison of both means and variability [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies in Bioequivalence Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Bioanalytical Methods | Quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices | Essential for measuring plasma/serum concentration-time profiles [11] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalization of extraction efficiency and instrument variability | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) bioanalysis [11] |

| Clinical Protocol with Crossover Design | Controlled administration of test and reference formulations | 2x2 crossover or replicated designs to minimize between-subject variability [23] [11] |

| Pharmacokinetic Modeling Software | Calculation of AUC, Cmax, Tmax, and other parameters | Non-compartmental analysis of concentration-time data [23] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Implementation of ANOVA, TOST, and confidence interval methods | SAS, R, or other validated platforms for BE statistical analysis [23] |

Practical Implementation and Case Study

Example Bioequivalence Assessment

A practical example from a 2×2 crossover bioequivalence study with 28 healthy volunteers illustrates the implementation process [23]. The study measured AUC and Cmax for test and reference formulations, with natural logarithmic transformation applied before statistical analysis. The analysis yielded the following results:

Table 4: Example Bioequivalence Study Results

| Parameter | Estimate for ln(μR/μT) | Estimate for μR/μT | 90% CI for μR/μT | BE Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 0.0893 | 1.09 | (0.89, 1.34) | Not equivalent (CI exceeds 1.25) |

| Cmax | -0.104 | 0.90 | (0.75, 1.08) | Not equivalent (CI below 0.80) |

In this case, neither parameter's 90% confidence interval fell entirely within the 80-125% range, so bioequivalence could not be concluded, and the FDA would not approve the generic product based on this study [23].

Common Methodological Pitfalls

Several common issues can compromise bioequivalence studies:

- Inadequate sample size: Underpowered studies may fail to demonstrate equivalence even when products are truly equivalent [18]

- Inappropriate subject population: Healthy volunteers may not represent patients for certain drug classes

- Protocol deviations: Poor compliance, vomiting, or dropouts can reduce evaluable data

- Analytical issues: Lack of assay validation or poor precision can introduce variability

- Incorrect statistical analysis: Failure to use appropriate models or account for period effects

Bioequivalence trials represent a specialized application of equivalence testing principles within pharmaceutical regulation, with well-established statistical and methodological frameworks. The current approach centered on average bioequivalence with 80-125% criteria has successfully ensured therapeutic equivalence of generic drugs while promoting competition and accessibility.

Ongoing harmonization initiatives through ICH and other international bodies continue to refine and standardize bioequivalence requirements across jurisdictions. Future developments may include greater acceptance of model-based bioequivalence approaches, further refinement of methods for highly variable drugs, and potential expansion of biowaiver provisions based on the Biopharmaceutical Classification System.

For researchers designing equivalence studies in other domains, the rigorous framework developed for bioequivalence assessment offers valuable insights into appropriate statistical methods, study design considerations, and regulatory standards for demonstrating therapeutic equivalence without undertaking large-scale clinical endpoint studies.

Implementing Equivalence Tests: From TOST to Advanced Model Averaging

A Guide to Statistical Tests for Model Performance Equivalence

In model performance evaluation, a non-significant result from a traditional null hypothesis significance test (NHST) is often—and incorrectly—interpreted as evidence of equivalence. The Two One-Sided T-Test (TOST) procedure rectifies this by providing a statistically rigorous framework to confirm the absence of a meaningful effect, establishing that differences between models are practically insignificant [9] [5]. This guide details the protocol for conducting a TOST, complete with experimental data and workflows, to objectively assess model equivalence in research and development.

Understanding the TOST Procedure

The TOST procedure is a foundational method in equivalence testing. Unlike traditional t-tests that aim to detect a difference, TOST is designed to confirm the absence of a meaningful difference by testing whether the true effect size lies within a pre-specified range of practical equivalence [24] [9].

- Core Hypotheses: In TOST, the roles of the null and alternative hypotheses are reversed from traditional testing.

- Null Hypothesis (Hâ‚€): The effect is outside the equivalence bounds (i.e., a meaningful difference exists). Formally, this is stated as ( H{01}: \theta \leq -\Delta ) or ( H{02}: \theta \geq \Delta ), where ( \theta ) is the population parameter (e.g., mean difference) and ( \Delta ) is the equivalence margin [24] [3].

- Alternative Hypothesis (Hâ‚): The effect is inside the equivalence bounds (i.e., no meaningful difference). Formally, ( -\Delta < \theta < \Delta ) [24].

- The TOST Method: To test these hypotheses, TOST performs two one-sided tests [24] [5]:

- Test if the effect is greater than the lower bound (( -\Delta )).

- Test if the effect is less than the upper bound (( \Delta )). If both tests are statistically significant, the null hypothesis is rejected, and we conclude equivalence.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details the essential components for designing and executing a TOST analysis.

| Item | Function in TOST Analysis |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R/Python/SAS) | Provides computational environment for executing two one-sided t-tests and calculating confidence intervals. The TOSTER package in R is a dedicated toolkit [19]. |

| Pre-Specified Equivalence Margin ((\Delta)) | A pre-defined, context-dependent range ([(-\Delta, \Delta)]) representing the largest difference considered practically irrelevant. This is the most critical reagent [5] [3]. |

| Dataset with Continuous Outcome | The raw data containing the continuous performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, MAE) of the two models or groups being compared. |

| Power Analysis Tool | Used prior to data collection to determine the minimum sample size required to have a high probability of declaring equivalence when it truly exists [9]. |

Experimental Protocol for a Two-Sample TOST

This protocol outlines the steps to test the equivalence of means between two independent groups, such as two different machine learning models.

Step 1: Define the Equivalence Margin Before collecting data, define the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI), which sets your equivalence margin, (\Delta) [9] [3]. This margin must be justified based on domain knowledge, clinical significance, or practical considerations. For example, in bioequivalence studies for drug development, a common margin for log-transformed parameters is ([log(0.8), log(1.25)]) [16]. For standardized mean differences (Cohen's d), bounds of -0.5 and 0.5 might be used [24].

Step 2: Formulate the Hypotheses Set up your statistical hypotheses based on the pre-defined margin.

- Hâ‚€: The true mean difference ( \mu1 - \mu2 \leq -\Delta ) or ( \mu1 - \mu2 \geq \Delta ). (The models are not equivalent.)

- Hâ‚: The true mean difference ( -\Delta < \mu1 - \mu2 < \Delta ). (The models are equivalent.)

Step 3: Calculate the Test Statistics and P-values Conduct two separate one-sided t-tests. For each test, you will calculate a t-statistic and a corresponding p-value [24] [17].

- Test 1 (vs. the lower bound): ( t1 = \frac{(\bar{X}1 - \bar{X}2) - (-\Delta)}{sp \sqrt{\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n2}}} ) where ( \bar{X} ) is the sample mean, ( n ) is the sample size, and ( s_p ) is the pooled standard deviation.

- Test 2 (vs. the upper bound): ( t2 = \frac{(\bar{X}1 - \bar{X}2) - \Delta}{sp \sqrt{\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n2}}} )

Step 4: Make a Decision Based on the P-values The overall p-value for the TOST procedure is the larger of the two p-values from the one-sided tests [5] [17]. If this p-value is less than your chosen significance level (typically ( \alpha = 0.05 )), you reject the null hypothesis and conclude statistical equivalence.

Step 5: Interpret Results Using a Confidence Interval An equivalent and often more intuitive way to interpret TOST is with a 90% Confidence Interval [24] [5]. Why 90%? Because TOST is performed at the 5% significance level for each tail, corresponding to a 90% two-sided CI.

- If the entire 90% confidence interval for the mean difference falls entirely within the equivalence bounds ([-\Delta, \Delta]), you can declare equivalence.

Figure 1: The logical workflow for conducting and interpreting a TOST equivalence test, showing the parallel paths of using p-values and confidence intervals.

Example: Equivalence of Two Model Performances

Suppose you have developed a new, computationally efficient model (Model B) and want to test if its performance is equivalent to your established baseline (Model A). You define the equivalence margin as a difference of 0.5 in Mean Absolute Error (MAE), a practically insignificant amount in your domain.

Experimental Data: After running both models on a test set, you collect the following MAE values:

| Model | Sample Size (n) | Mean MAE | Standard Deviation (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | 50 | 10.2 | 1.8 |

| Model B | 50 | 10.4 | 1.9 |

TOST Analysis:

- Equivalence Margin: ( \Delta = 0.5 )

- Observed Mean Difference: ( 10.4 - 10.2 = 0.2 )

- Pooled Standard Deviation: ( s_p \approx 1.85 )

- 90% Confidence Interval for the Difference:

[-0.15, 0.55](hypothetical calculation for illustration). - TOST P-values: The p-value for the test against the lower bound (-0.5) is 0.001; against the upper bound (0.5) is 0.036 [17]. The overall TOST p-value is 0.036.

Interpretation: While the observed difference (0.2) is within the [-0.5, 0.5] margin, the 90% confidence interval [-0.15, 0.55] slightly exceeds the upper bound. Consequently, despite one of the p-values being significant, the TOST procedure would fail to confirm full equivalence because the 90% CI is not entirely contained within the equivalence bounds [24] [5]. This outcome demonstrates the conservativeness and rigor of the TOST method.

TOST vs. Traditional T-Test

The table below summarizes the key philosophical and procedural differences between the two approaches.

| Feature | Traditional NHST T-Test | TOST Equivalence Test |

|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis (Hâ‚€) | The means are exactly equal (effect size = 0). | The effect is outside the equivalence bounds (a meaningful difference exists). |

| Alternative Hypothesis (Hâ‚) | The means are not equal (an effect exists). | The effect is within the equivalence bounds (no meaningful difference). |

| Primary Goal | Detect any statistically significant difference. | Establish practical similarity or equivalence. |

| Interpretation of a non-significant p-value | "No evidence of a difference" (but cannot claim equivalence). | Test is inconclusive; cannot claim equivalence [24] [9]. |

| Key Output for Decision | 95% Confidence Interval (checks if it includes 0). | 90% Confidence Interval (checks if it lies entirely within [–Δ, Δ]) [24] [5]. |

Key Considerations for Practitioners

- Justifying the Equivalence Margin: The most critical and often challenging step is choosing a defensible ( \Delta ). This should be based on substantive knowledge, not statistical properties. In model performance, it could be the smallest loss in accuracy that is meaningful to the application [5] [3].

- Power and Sample Size: Equivalence tests require sufficient statistical power to reject the presence of a meaningful effect. A priori power analysis for TOST is essential to ensure your study is informative; underpowered tests will fail to confirm equivalence even if it holds [9] [19].

- One-Sided Tests: Non-Inferiority: Sometimes the research question is only whether a new model is not worse than an existing one by a margin. This is a non-inferiority test, which is a simplified, one-sided version of TOST where you only test against the lower equivalence bound [24] [3].

The TOST procedure empowers researchers in drug development and data science to move beyond simply failing to find a difference and instead build positive evidence for the equivalence of models, treatments, or measurement methods. By rigorously defining an equivalence margin and following the structured protocol outlined above, professionals can generate robust, statistically sound, and practically meaningful conclusions about model performance.

In statistical modeling, particularly in regression analysis, a fundamental challenge is that the true data-generating process is nearly always unknown. This issue, termed model uncertainty, refers to the imperfections and idealizations inherent in every physical model formulation [25]. Model uncertainty arises from simplifying assumptions, unknown boundary conditions, and the effects of variables not included in the model [25]. In practical terms, this means that even with perfect knowledge of input variables, our predictions of system responses will contain uncertainty beyond what comes from the basic input variables themselves [25].

The consequences of ignoring model uncertainty can be severe, leading to overconfident predictions, inflated Type I errors, and ultimately, unreliable scientific conclusions [26]. In high-stakes fields like drug development, where this guide is particularly focused, such overconfidence can translate to costly clinical trial failures or missed therapeutic opportunities. Researchers have broadly categorized uncertainty into two main types: epistemic uncertainty, which stems from a lack of knowledge and is potentially reducible with more data, and aleatoric uncertainty, which represents inherent stochasticity in the system and is generally irreducible [27] [28].

This guide examines contemporary approaches for addressing model uncertainty, with particular emphasis on statistical equivalence testing and model averaging techniques that have shown promise for validating model performance when the true regression model remains unknown.

Quantifying and Classifying Model Uncertainty

Fundamental Classification of Uncertainty

Model uncertainty manifests in several distinct forms, each requiring different handling strategies. The literature generally recognizes three primary classifications of model uncertainty [29]:

- Uncertainty about the true model: This encompasses uncertainty regarding the functional form, distributional assumptions, and relevant variables in the data-generating process.

- Model selection uncertainty: The inherent randomness in model selection results, where different models may be selected from the same data-generating process using different data samples.

- Model selection instability: The phenomenon where slight changes in data lead to significantly different selected models, despite using the same selection procedure.

From a practical perspective, uncertainty is also categorized based on its reducibility [27] [28]:

- Epistemic uncertainty: Arises from limited data or knowledge and can theoretically be reduced with additional information.

- Aleatoric uncertainty: Stems from inherent stochasticity in the system and persists regardless of data quantity.

These uncertainty types collectively contribute to the total predictive uncertainty that researchers must quantify and manage, particularly in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development.

Mathematical Formalization of Model Uncertainty

The discrepancy between model predictions and true system behavior can be formalized as:

[ X{\text{true}} = X{\text{pred}} \times B ]

where (B) represents the model uncertainty, characterized probabilistically through multiple observations and predictions [25]. The mean of (B) expresses bias in the model, while the standard deviation captures the variability of model predictions [25].

In computational terms, the relationship between observations and model predictions can be expressed as:

[ y^e(\mathbf{x}) = y^m(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\theta}^*) + \delta(\mathbf{x}) + \varepsilon ]

where (y^e(\mathbf{x})) represents experimental observations, (y^m(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\theta}^)) represents model predictions with calibrated parameters (\boldsymbol{\theta}^), (\delta(\mathbf{x})) represents model discrepancy (bias), and (\varepsilon) represents random observation error [28].

Statistical Frameworks for Handling Model Uncertainty

Equivalence Testing for Model Validation

Traditional hypothesis testing frameworks are fundamentally misaligned with model validation objectives. In standard statistical testing, the null hypothesis typically assumes no difference, placing the burden of proof on demonstrating model inadequacy [30]. Equivalence testing reverses this framework, making the null hypothesis that the model is not valid (i.e., that it exceeds a predetermined accuracy threshold) [30].

The core innovation of equivalence testing is the introduction of a "region of indifference" within which differences between model predictions and experimental data are considered negligible [30]. This region is implemented as an interval around a nominated metric (e.g., mean difference between predictions and observations). If a confidence interval for this metric falls completely within the region of indifference, the model is deemed significantly similar to the true process [30].

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Testing Approaches for Model Validation

| Testing Approach | Null Hypothesis | Burden of Proof | Interpretation of Non-Significant Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Testing | Model is accurate | Prove model wrong | Insufficient evidence to reject (inconclusive) |

| Equivalence Testing | Model is inaccurate | Prove model accurate | Evidence that model meets accuracy standards |

The Two One-Sided Test (TOST) procedure operationalizes this approach by testing whether the mean difference between predictions and observations is both significantly greater than the lower equivalence bound and significantly less than the upper equivalence bound [30]. This method provides a statistically rigorous framework for demonstrating model validity rather than merely failing to demonstrate invalidity.

Model Averaging Approaches

Model averaging has emerged as a powerful alternative to traditional model selection for addressing model uncertainty. Rather than selecting a single "best" model from a candidate set, model averaging incorporates information from multiple plausible models, providing more robust inference and prediction [26].

The primary advantage of model averaging over model selection is its stability—minor changes in data are less likely to produce dramatically different results [26]. This stability is particularly valuable in drug development contexts where decisions have significant financial and clinical implications.

Table 2: Model Averaging Techniques for Addressing Model Uncertainty

| Technique | Basis for Weights | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smooth AIC Weights | Akaike Information Criterion | Frequentist approach; asymptotically equivalent to Mallows CP | General regression modeling |

| Smooth BIC Weights | Bayesian Information Criterion | Approximates posterior model probabilities | Bayesian model averaging |

| FIC Weights | Focused Information Criterion | Optimizes for specific parameter of interest | Targeted inference problems |

| Bayesian Model Averaging | Posterior model probabilities | Fully Bayesian framework; incorporates prior knowledge | Small to moderate sample sizes |

Model averaging is particularly valuable in dose-response studies and time-response modeling, where the true functional form is rarely known with certainty [26]. By combining estimates from multiple candidate models (e.g., linear, quadratic, Emax, sigmoidal), researchers can obtain more reliable inferences while explicitly accounting for model uncertainty.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Model Uncertainty

Protocol 1: Equivalence Testing for Regression Curves

Objective: To test whether two regression curves (e.g., from different patient populations or experimental conditions) are equivalent over the entire covariate range.

Methodology:

- Define equivalence threshold: Establish a clinically or scientifically meaningful threshold for the maximum acceptable difference between curves (e.g., Δ = 0.5 on the response scale).

- Select distance measure: Choose an appropriate distance measure between curves, such as the maximum absolute distance ((L_\infty)) or integrated squared difference.

- Calculate confidence interval: Derive a confidence interval for the selected distance measure using appropriate techniques (e.g., bootstrap methods).

- Test equivalence: Compare the confidence interval to the equivalence threshold. If the entire interval falls within [-Δ, Δ], conclude equivalence.

This approach overcomes limitations of traditional methods that test equivalence only at specific points (e.g., mean responses or AUC) rather than across the entire functional relationship [26].

Protocol 2: Model Averaging for Dose-Response Analysis

Objective: To estimate a dose-response relationship while accounting for uncertainty in the functional form.

Methodology:

- Specify candidate models: Identify a set of biologically plausible models (e.g., linear, Emax, sigmoid Emax, exponential).

- Estimate model weights: Compute weights for each model using an information criterion (e.g., AIC, BIC) or Bayesian approach.

- Compute averaged prediction: For any given dose level, compute the weighted average of predictions from all models.

- Quantify uncertainty: Calculate prediction intervals that incorporate both within-model and between-model uncertainty.

This protocol explicitly acknowledges that no single model perfectly represents the true relationship, providing more honest uncertainty quantification [26].

Visualization of Uncertainty Quantification Workflows

Diagram 1: Uncertainty Quantification Workflow for Regression Modeling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Addressing Model Uncertainty

| Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) | Tests whether parameter falls within equivalence range | Model validation; bioequivalence assessment |

| Smooth AIC/BIC Weights | Computes model weights for averaging | Multi-model inference and prediction |

| Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) | Averages models using posterior probabilities | Bayesian analysis with model uncertainty |

| Monte Carlo Dropout | Estimates uncertainty in neural networks | Deep learning applications |

| Deep Ensembles | Combines predictions from multiple neural networks | Uncertainty quantification in deep learning |

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion | Represents uncertainty via orthogonal polynomials | Engineering and physical models |

| Bootstrap Confidence Intervals | Estimates sampling distributions | Non-parametric uncertainty quantification |

Comparative Performance of Uncertainty Quantification Methods

Recent research has systematically evaluated various approaches for handling model uncertainty across different application domains.

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Uncertainty Quantification Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Strengths | Limitations | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equivalence Testing | Frequentist hypothesis testing | Clear decision rule; regulatory acceptance | Requires pre-specified equivalence margin | Low to moderate |

| Model Averaging | Information theory or Bayesian | Robust to model misspecification; incorporates model uncertainty | Weight determination can be sensitive to candidate set | Moderate |

| Bayesian Neural Networks | Bayesian probability | Natural uncertainty representation; principled framework | Computationally intensive; prior specification challenges | High |

| Deep Ensembles | Frequentist ensemble methods | State-of-the-art for many applications; scalable | Multiple training required; less interpretable | High |

| Gaussian Processes | Bayesian nonparametrics | Flexible uncertainty estimates; closed-form predictions | Poor scalability to large datasets | High for large n |

In pharmaceutical applications, studies have demonstrated that model averaging approaches maintain better calibration and predictive performance compared to model selection when substantial model uncertainty exists [26]. Similarly, equivalence testing provides a more appropriate framework for model validation compared to traditional hypothesis testing, particularly in bioequivalence studies and model-based drug development [30].

Model uncertainty presents a fundamental challenge in regression modeling and drug development. By acknowledging that all models are approximations and explicitly quantifying the associated uncertainties, researchers can make more reliable inferences and predictions. The approaches discussed in this guide—particularly equivalence testing and model averaging—provide powerful frameworks for handling model uncertainty in practice.

The choice of method depends on the specific research context, with equivalence testing offering a rigorous approach for model validation against experimental data, and model averaging providing robust inference when multiple plausible models exist. As the field advances, the integration of these approaches with modern machine learning techniques promises to further enhance our ability to quantify and manage uncertainty in complex biological systems.

Leveraging Model Averaging with Smooth BIC Weights for Robust Inference

In scientific research, particularly in fields like drug development and toxicology, statistical inference often faces a fundamental challenge: model uncertainty. When multiple statistical models can plausibly describe the same dataset, relying on a single selected model can lead to overconfident inferences and poor predictive performance. This problem is especially pronounced in dose-response studies, genomics, and risk assessment, where the true data-generating process is complex and imperfectly understood [31] [26].

Model averaging has emerged as a powerful solution to this problem, with smooth BIC weighting representing one of the most rigorous implementations of this approach. Unlike traditional model selection which chooses a single "best" model, model averaging combines estimates from multiple candidate models, thereby accounting for uncertainty in the model selection process itself [32] [33]. This approach recognizes that different models capture different aspects of the truth, and that a weighted combination often provides more robust inference than any single model.

Frequentist model averaging using smooth BIC weights is particularly valuable for equivalence testing and dose-response analysis, where it helps overcome the limitations of model misspecification [26]. By distributing weight across models according to their statistical support, researchers can reduce the influence of high-leverage points that often distort parametric inferences in poorly specified models [34]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of model averaging approaches, with particular emphasis on the performance characteristics of smooth BIC weighting relative to competing methods.

Theoretical Foundations: How Model Averaging Mitigates Model Uncertainty

The Framework of Model Averaging

Model averaging operates on a simple but powerful principle: rather than selecting a single model from a candidate set, we combine estimates from all models using carefully chosen weights. For a parameter of interest μ, the model averaging estimate takes the form:

[ \hat{\mu}{MA} = \sum{m=1}^{M} wm \hat{\mu}m ]

where (\hat{\mu}m) is the estimate of μ from model m, and (wm) are weights assigned to each model, with (\sum{m=1}^{M} wm = 1) and (w_m \geq 0) [32]. The theoretical justification for this approach stems from recognizing that model selection introduces additional variability that is typically ignored in post-selection inference [33].

The performance of model averaging critically depends on how the weights are determined. Different weighting schemes have been proposed, including:

- Smooth AIC weights: Based on the Akaike Information Criterion

- Smooth BIC weights: Based on the Bayesian Information Criterion

- Frequentist model averaging: Minimizing Mallows' criterion or using cross-validation

- Bayesian model averaging (BMA): Based on posterior model probabilities [35] [36]

Smooth BIC Weighting Mechanism

Smooth BIC weighting employs the Bayesian Information Criterion to determine model weights. For a set of M candidate models, the weight for model m is calculated as:

[ wm^{BIC} = \frac{\exp(-\frac{1}{2} \Delta BICm)}{\sum{j=1}^{M} \exp(-\frac{1}{2} \Delta BICj)} ]

where (\Delta BICm = BICm - \min(BIC)) is the difference between the BIC of model m and the minimum BIC among all candidate models [26] [32]. The BIC itself is defined as:

[ BICm = -2 \cdot \log(Lm) + k_m \cdot \log(n) ]

where (Lm) is the maximized likelihood value for model m, (km) is the number of parameters, and n is the sample size.

The BIC approximation has strong theoretical foundations in Bayesian statistics, as it approximates the log posterior odds between models under specific prior assumptions [35]. This connection to Bayesian methodology gives smooth BIC weights a solid theoretical justification beyond mere algorithmic convenience.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Model Averaging Weighting Schemes