Beyond the Local Peak: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Local Optima in Genetic Algorithms for Drug Discovery

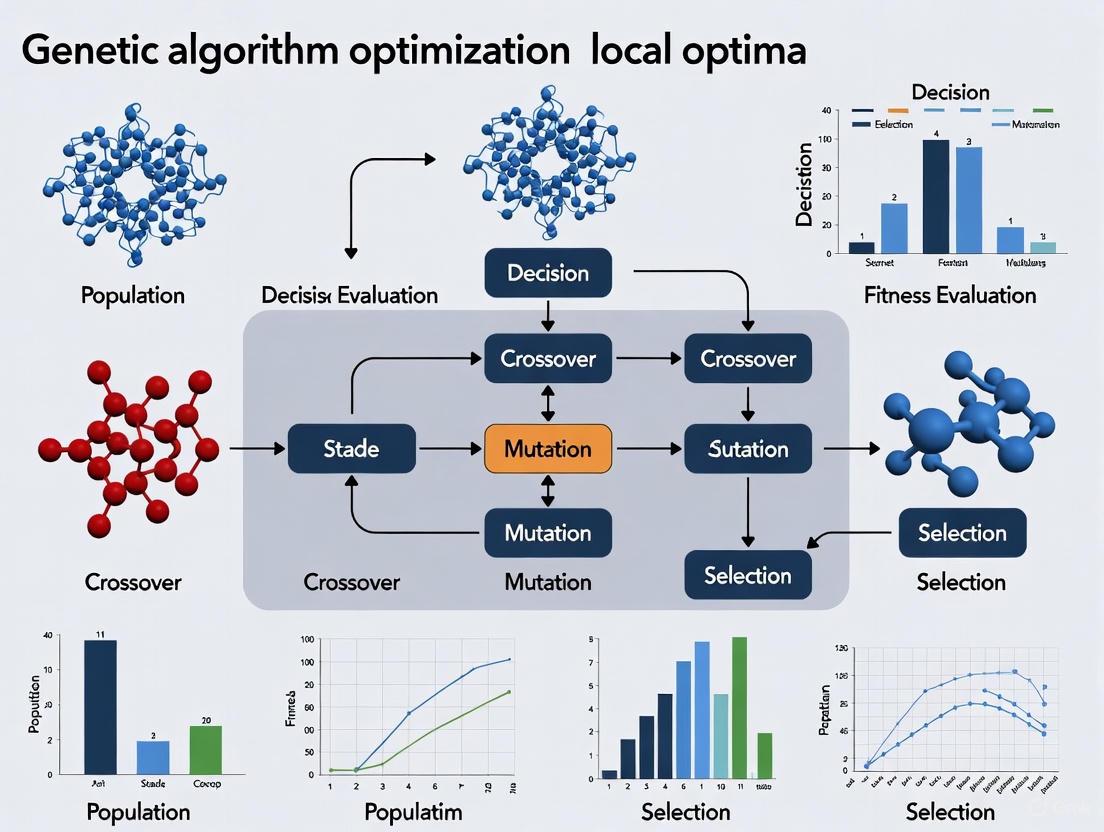

This article addresses the critical challenge of local optima in genetic algorithm (GA) optimization, a significant bottleneck in complex biomedical research problems like drug design and metabolic interaction prediction.

Beyond the Local Peak: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Local Optima in Genetic Algorithms for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of local optima in genetic algorithm (GA) optimization, a significant bottleneck in complex biomedical research problems like drug design and metabolic interaction prediction. We explore the foundational theory of local optima and their impact on GA performance, then delve into advanced hybrid methodologies such as chaos theory integration and reinforced GAs that enhance global search capabilities. The guide provides actionable troubleshooting and optimization techniques, including population diversity management and adaptive operators, validated through comparative analysis with other optimization algorithms. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes cutting-edge strategies to improve the robustness, efficiency, and success rate of GA-driven discoveries in clinical and pharmaceutical applications.

Understanding the Maze: Defining Local Optima and Their Impact on Genetic Algorithm Convergence

What Are Local Optima? Mathematical Definitions and Practical Consequences in Search Spaces

Technical Definitions: Classifying Local Optima

In optimization, a local optimum is a solution that is the best within a particular region of the search space but is not necessarily the best overall solution (the global optimum) [1]. Imagine a landscape with hills and valleys: a local optimum is a hilltop higher than its immediate surroundings, but not the highest point in the entire landscape [2].

The following table summarizes the key mathematical definitions and tests for identifying local optima.

| Concept | Mathematical Definition | Test/Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Local Maximum | A point ( x^* ) where ( f(x^) \geq f(x) ) for all ( x ) in a neighborhood around ( x^ ) [3]. | For twice-differentiable functions: ( f'(x^) = 0 ) and ( f''(x^) < 0 ) [3]. |

| Local Minimum | A point ( x^* ) where ( f(x^) \leq f(x) ) for all ( x ) in a neighborhood around ( x^ ) [3]. | For twice-differentiable functions: ( f'(x^) = 0 ) and ( f''(x^) > 0 ) [3]. |

| Saddle Point | A stationary point that is neither a local maximizer nor a local minimizer [3]. | For a twice-differentiable function of two variables, a sufficient condition is that the determinant of the Hessian matrix at the point is negative [3]. |

| Global Optimum | The best possible solution across the entire search space [1]. | Often impossible to guarantee without exhaustive search, but can be approached with robust global optimization techniques. |

For functions of multiple variables, the Hessian matrix (H) of second-order partial derivatives is crucial. If H(( x^* )) is negative definite, then ( x^* ) is a local maximizer. If H(( x^* )) is positive definite, then ( x^* ) is a local minimizer [3]. A saddle point is often associated with an indefinite Hessian [3].

Visualizing the Problem: The Search Space Landscape

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different types of optima in a search space.

Optimization Search Space

Experimental Protocols: Investigating and Overcoming Local Optima

This section details a methodology from recent literature that explicitly addresses the challenge of local optima in a real-world optimization problem.

Case Study: Facility Layout Optimization with a Hybrid Genetic Algorithm

A 2025 study proposed a New Improved Hybrid Genetic Algorithm (NIHGA) to solve the facility layout problem in reconfigurable manufacturing systems, a complex challenge where traditional algorithms often converge to local optima [4].

1. Objective: To find a facility layout that minimizes material handling and reconfiguration costs, a problem known to have a complex, multi-modal search space [4].

2. Algorithm Workflow: The following diagram outlines the workflow of the NIHGA, highlighting components designed to avoid local optima.

NIHGA Workflow for Escaping Local Optima

3. Key Anti-Local-Optima Mechanisms:

- Chaotic Initialization: The initial population is generated using an improved Tent map from chaos theory. This ensures high diversity from the start, making premature convergence to a poor local optimum less likely [4].

- Dominant Block Mining: The algorithm uses association rule theory to identify "dominant blocks" (high-quality gene combinations) from the best individuals. This reduces problem complexity and guides the search more efficiently [4].

- Adaptive Chaotic Perturbation: After standard genetic operations (crossover and mutation), a small chaotic perturbation is applied specifically to the best solution. This acts as a targeted local search, helping to kick the solution out of a local optimum's basin of attraction [4].

4. Outcome: The NIHGA was shown to be superior to traditional methods in both accuracy and efficiency, demonstrating the effectiveness of its integrated approach to overcoming local optima [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Local Optima

Q1: My genetic algorithm converges quickly, but the solution is poor. Is this a sign of being trapped in a local optimum? A: Yes, premature convergence is a classic symptom. This occurs when a lack of population diversity causes the algorithm to exploit a small, sub-optimal region of the search space too early [2]. To confirm, run the algorithm multiple times from different random starting points. If it consistently converges to the same or similar sub-optimal solutions, you are likely dealing with a local optimum.

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between a local optimum and a saddle point? A: A local optimum is the best point in its immediate vicinity [2]. In contrast, a saddle point is a stationary point (where the gradient is zero) that is neither a local maximum nor minimum. At a saddle point, the function curves up in some directions and down in others [3]. While an algorithm may slow down near a saddle point, it is not trapped in the same way and can potentially escape by following a direction of descent.

Q3: How can I tell if my solution is a local vs. global optimum for a complex, real-world problem? A: For NP-hard problems, it is often impossible to guarantee a solution is globally optimal without an exhaustive search, which is computationally infeasible [4]. The best practice is to use strong global search techniques:

- Run the algorithm many times with different initial conditions.

- Use algorithms with built-in mechanisms for exploration (e.g., simulated annealing's occasional acceptance of worse solutions [2], or chaotic perturbation in GAs [4]).

- Compare results from different algorithms (e.g., compare a GA result with one from a Particle Swarm Optimization). A solution that is consistently found and is superior to others is a good candidate for the global optimum.

Q4: Are local optima always a bad thing? A: Not necessarily. In some applications, finding a "good enough" solution quickly is more important than finding the absolute best solution. Local search algorithms that converge to local optima can be highly efficient for providing satisfactory solutions in such complex search spaces [2]. The key is to know the requirements of your project.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and strategies used in the fight against local optima, as featured in the cited experiments.

| Tool / Strategy | Function in Optimization | Role in Overcoming Local Optima |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotic Maps (e.g., Tent Map) | A deterministic system that produces ergodic, non-repeating sequences. Used to initialize populations or generate perturbations [4]. | Enhances exploration by ensuring initial population diversity and applying non-random, adaptive perturbations to escape local attractors [4]. |

| Association Rule Learning | A rule-based machine learning method to find interesting relationships between variables in a database. Used for "dominant block mining" [4]. | Reduces problem complexity and guides the search by identifying and preserving high-quality building blocks (schemata) from fit individuals, preventing their disruption [4]. |

| Tabu Search | A metaheuristic that uses memory structures (a "tabu list") to record recently visited solutions [2] [5]. | Prevents cycling back to recently visited local optima, forcing the search to explore new, promising regions [2]. |

| Simulated Annealing | A probabilistic technique inspired by the annealing process in metallurgy. It occasionally accepts worse solutions [2]. | Allows the algorithm to "jump" out of local optima by accepting downhill moves, with the probability of such acceptance decreasing over time [2]. |

| Hybridization (e.g., GA-PSO) | Combining two or more optimization algorithms into a single pipeline [4]. | Leverages the strengths of different algorithms; for example, using GA for broad exploration and PSO for fine-tuned exploitation, balancing the search to avoid premature convergence [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequent Convergence Issues

FAQ 1: Why does my GA consistently converge to a suboptimal solution early in the process?

Problem: Premature convergence occurs when a population loses genetic diversity too quickly, causing the search to settle for a local optimum rather than the global one. This is often because an individual that is significantly fitter than others in a small population reproduces excessively, dominating the gene pool before the search space is adequately explored [6].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Symptom: The algorithm's performance improves rapidly in the first few generations but then stalls at a fitness level far below the known optimum.

- Verification: Monitor the population's diversity. A rapid drop in genotypic or phenotypic diversity metrics confirms this issue.

- Solutions:

- Increase Population Size: A small population does not provide enough solution space for accurate results. Increasing the size provides a more extensive search base [6].

- Adjust Selection Pressure: Using less aggressive selection methods (e.g., reducing the bias towards the very fittest individuals) can help maintain diversity. Consider Stochastic Universal Sampling or a lower scaling factor in roulette wheel selection to prevent a few "super individuals" from dominating early [7].

- Use Elitism Judiciously: While elitism (carrying the best individuals to the next generation) helps preserve good solutions, an elite group that is too large can reduce diversity and stall progress. A common configuration is to select only the top 10% as elites [7].

- Implement "Competitive Immigrants": Instead of adding purely random immigrants, create competitive ones by mating a random immigrant with a selected parent from the population. This introduces new genetic material in a more competitive form, helping to maintain diversity and fitness throughout the run [8].

FAQ 2: Why does my GA fail to find better solutions even after many generations, despite having diversity?

Problem: The algorithm has converged, potentially to a local optimum, and the standard genetic operators (crossover and mutation) are not powerful enough to escape this region of the search space. The "building blocks" (high-quality schemata) may not be being effectively identified and combined [9] [10].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Symptom: The average and best fitness of the population have reached a plateau for a significant number of generations without improvement.

- Verification: Analyze the effectiveness of crossover. If offspring are not significantly different or better than their parents, the crossover operator may be ineffective.

- Solutions:

- Adopt Deep Crossover Schemes: Traditional crossover performs a single recombination, producing only two offspring per parent pair. Deep crossover performs multiple recombination steps with the same parent pair, allowing for a more intensive exploitation of the parental genes and a higher probability of discovering high-quality gene patterns (building blocks) [10]. The workflow for a two-level deep crossover is illustrated below.

- Tune Mutation Parameters: A mutation rate that is too low may lead to genetic drift and an inability to escape local optima. Conversely, a rate that is too high can destroy good solutions. Increase the mutation rate slightly from very low settings (e.g., 0.5%), but use elitism to protect the best-found solutions [9] [8].

- Employ Speciation Heuristics: Penalize crossover between candidate solutions that are too similar. This encourages population diversity and helps prevent the entire population from clustering around a local optimum [9].

Diagram 1: Deep Crossover with Two Levels. This shows how multiple crossover operations on a parent pair create a larger, more diverse offspring pool for selection.

FAQ 3: Why does my GA performance degrade when I move from a test function to my real-world computational model?

Problem: The fitness function evaluation for complex, high-dimensional real-world problems (e.g., biophysical models of drug interaction or neural stimulation) is often computationally prohibitive. Repeated expensive evaluations become the bottleneck, and the GA may not get enough generations to find a good solution [9] [8].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Symptom: The algorithm is slow, and each generation takes a very long time to compute. Progress is minimal relative to the computational time invested.

- Verification: Profile your code. If over 90% of the time is spent on the fitness function evaluation, this is the limiting factor.

- Solutions:

- Use Approximate Fitness Models: Replace the exact, computationally expensive fitness function with a faster, approximated version (e.g., a surrogate model like a neural network or Gaussian process) for the majority of generations, only using the exact function for validation [9].

- Modify Mutation for the Domain: Standard binary mutation can bias the solution. For temporal pattern optimization (e.g., in neuromodulation), a Pulse Mutation Method (PMM) is more effective. Instead of flipping bits, which biases the pulse frequency, PMM randomly chooses to add, remove, or move a pulse, introducing no frequency bias [8].

- Implement Variable Pattern Length (VPL): For problems involving pattern design, start with shorter patterns for faster convergence in early generations. Then progressively increase the pattern length across generations by replicating and concatenating sub-segments, allowing the discovery of low-frequency features without sacrificing initial speed [8].

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Standard Operator Limitations

Protocol 1: Implementing and Benchmarking a Deep Crossover Scheme

This protocol is based on research that introduced deep crossover schemes to enhance the canonical GA's performance on combinatorial problems like the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) [10].

1. Objective: To evaluate whether deep crossover schemes can produce better solutions than the canonical GA by reducing the chance of getting stuck in local optima.

2. Methodology:

- Algorithm Design:

- Control: Canonical GA with a single crossover operation per parent pair.

- Intervention: Implement a GA with a deep crossover scheme (e.g., 2-level, 3-level). At each mating event, the selected parent pair undergoes crossover multiple times, creating a pool of offspring (e.g., 4 offspring for 2-level, 8 for 3-level). The best offspring from this pool are then selected for the next generation.

- Benchmark Problem: Use standard TSP instances (e.g., from TSPLIB).

- Performance Metric: Use the Gap metric to measure the percentage deviation of the algorithm's solution from a known optimum or a best-known solution.

- Parameters:

- Population size: 500

- Crossover type: Ordered Crossover (OX)

- Mutation: Swap mutation (2%)

- Selection: Tournament selection

3. Key Findings Summary (Comparative Data): The following table summarizes hypothetical results based on the described research, showing how different deep crossover configurations might perform against the canonical GA [10].

| Algorithm Variant | Average Gap (%) (over 10 runs) | Generations to Converge | Computational Time per Run (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical GA | 5.2% | 150 | 120 |

| GA with 2-Level Crossover | 3.1% | 110 | 155 |

| GA with 3-Level Crossover | 2.7% | 95 | 190 |

| GA with Memetic Crossover | 2.9% | 100 | 165 |

Table 1: Sample Performance Comparison of Deep Crossover Schemes on TSP. Data is illustrative of trends reported in research [10].

Protocol 2: Modifying GA Repopulation for Biomedical Pattern Design

This protocol is derived from a study that designed optimal temporal patterns of electrical neuromodulation for neurological therapy, a problem relevant to computational drug and therapy development [8].

1. Objective: To test modified GA repopulation strategies for improving convergence speed and accuracy in designing binary temporal patterns.

2. Methodology:

- Control: A standard GA with roulette wheel selection, two-point crossover, probabilistic bit-flip mutation (0.5%), and random immigrants.

- Intervention Group: A modified GA incorporating:

- Pulse Mutation Method (PMM): As described in FAQ 3.

- Competitive Immigrants (CI): As described in FAQ 1.

- Variable Pattern Length (VPL): Start with a base pattern length (e.g., 1/10 of final length) and increase it over generations.

- Predictive Immigrants (PI): Track features of high-scoring patterns and generate new immigrants that incorporate these features.

- Evaluation: Test on both benchmark functions and a biophysically-based computational model of neural stimulation. The fitness function is specific to the therapeutic goal (e.g., activating a specific neural population while avoiding others).

3. Workflow: The following diagram outlines the modified GA repopulation process, highlighting the introduced strategies.

Diagram 2: Modified GA Repopulation Workflow. Dashed lines indicate the non-standard modifications added to the canonical GA process to improve performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details essential "methodological reagents" for experiments aimed at overcoming the limitations of standard GA operators.

| Research Reagent | Function / Role in Experiment | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Crossover Scheme | A multi-level recombination operator that performs crossover multiple times on the same parent pair to intensify the search for good "building blocks." | Used to investigate complex variable interactions and improve the inheritance of good genes [10]. Variants include 2-level, 3-level, and memetic crossover. |

| Pulse Mutation Method (PMM) | A domain-specific mutation operator for temporal pattern design that prevents bias in average pulse frequency by adding, removing, or moving pulses. | Critical for applications in neuromodulation therapy design where maintaining a specific pulse density is important [8]. |

| Competitive Immigrants (CI) | A diversity-maintenance mechanism that creates immigrants by mating a random individual with a high-fitness parent, making new genetic material more competitive. | Helps prevent premature convergence without degrading the average population fitness, as pure random immigrants often do [8]. |

| Speciation Heuristic | A penalization mechanism applied during selection or crossover that discourages mating between solutions that are genotypically too similar. | Promotes population diversity and helps the algorithm explore different regions of the search space in parallel, avoiding a single local optimum [9]. |

| Surrogate Fitness Model | A computationally efficient approximate model (e.g., Neural Network, Linear Regression) used in place of an expensive, high-fidelity simulation. | Allows for a much higher number of generations to be run when facing budget or time constraints for fitness evaluation [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a local optimum and why is it a problem in drug discovery? A local optimum is a solution that is the best within its immediate "neighborhood" of possible solutions but is not the absolute best solution (the global optimum) for the entire problem. In drug discovery, this means an algorithm might settle on a molecular structure or a drug interaction prediction that seems good initially but is ultimately suboptimal. This can lead to missed opportunities for more effective, safer, or cheaper drugs, contributing to the high cost and slow pace of development [11] [12].

My GA for molecular optimization is converging too quickly to similar structures. What can I do? Quick convergence often indicates that your population lacks diversity and is trapped in a local optimum. Strategies to overcome this include:

- Implement Elitism with Caution: While carrying the best performers to the next generation is good, ensure it doesn't dominate the gene pool. Decouple the number of elite compounds from those used to seed new mutations and crossovers to maintain diversity [13].

- Hybrid Algorithms: Combine a global search algorithm (like a GA or Differential Evolution) with a local search method (like Sequential Least Squares Programming). This allows a broad exploration of the chemical space followed by a refined local search, providing a trade-off between finding global optima and computational efficiency [14].

How can I improve the chemical diversity of molecules generated by my evolutionary algorithm?

- Utilize Diverse Reaction Sets: Use a large and diverse library of in silico chemical reactions (e.g., the 94-reaction set in AutoGrow4) to perform mutations. This expands the range of possible chemical transformations beyond simple modifications [13].

- Inspect Complementary Libraries: The small-molecule fragments used in reactions significantly impact diversity. Use filtered, commercially available fragment libraries (e.g., from ZINC15) that are rich in different functional groups to enable the generation of novel structures [13].

My DDI prediction model has high accuracy but low real-world applicability. What am I missing? This is a common issue when models learn statistical correlations instead of underlying biological mechanisms. To improve real-world relevance:

- Incorporate Mechanistic Data: Move beyond just structural features. Integrate data on specific mechanisms like Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME), as well as drug-target pathways. Models like DDINet that predict mechanism-wise interactions (e.g., excretion, metabolism) offer more interpretable and actionable results [15].

- Leverage Multi-Model Data: Combine different data types, such as molecular graphs (for structural information) and knowledge graphs (for known interactions and biological pathways), to create a more holistic model. Techniques like Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) are well-suited for this [16].

Are deep learning models a solution to the local optima problem? Deep learning (DL) can be a powerful component of a solution, but it is not a silver bullet. DL models can act as highly accurate fitness functions to guide an evolutionary algorithm, evaluating complex properties more effectively than simple scoring functions [17]. They can also be used as decoders to convert evolved molecular fingerprints (like ECFP) back into valid chemical structures (SMILES strings), ensuring chemical validity during evolution without relying on hard-coded rules [17]. However, DL models themselves can get stuck in local optima during training.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Population Diversity Loss in Molecular Optimization

Symptoms: The genetic algorithm converges on very similar molecules within a few generations. The fitness score stops improving early, and the best compounds share a common, limited chemical scaffold.

Diagnosis: The algorithm is likely trapped in a local optimum, unable to explore a wider chemical space.

Solutions:

- Adjust Genetic Operator Parameters:

- Increase Mutation Rate: Temporarily increase the mutation rate to introduce more randomness and explore new regions of the chemical space.

- Diversify Crossover: Ensure the crossover operator is recombining genetically distinct parents, not just similar ones.

- Implement a Hybrid DE-SLSQP Approach: For complex optimization problems, such as designing non-equally spaced arrays (an analogy for complex molecular scaffolds), a hybrid method can be highly effective [14]. The framework below illustrates how this strategy balances global and local search:

Table 1: Key Parameters for the DE-SLSQP Hybrid Algorithm [14]

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Population Size | 20 individuals | Balances diversity with computational cost. |

| Individual Encoding | Excitation vector x→ ∈ [-1,1]^2N |

Represents the design variables (e.g., molecular features). |

| Spacing Distance | d→ ∈ [0.4,1]^N-1 |

Constrains the structure to feasible configurations. |

| Stopping Condition | Maximum generations | Controls the duration of the global search. |

Problem 2: Poor Generalization in DDI Prediction Models

Symptoms: The model performs well on training data but fails to predict novel or previously unseen drug-drug interactions. Predictions lack biological plausibility.

Diagnosis: The model is overfitting to correlations in the training data and not learning the underlying causal molecular mechanisms.

Solutions:

- Adopt a Mechanism-Wise Deep Learning Architecture: Implement a model like DDINet, which uses deep sequential learning (LSTM, GRU) with an attention mechanism to predict and classify DDIs based on specific biological mechanisms (e.g., Metabolism, Excretion) [15]. This forces the model to learn features relevant to how drugs actually interact in the body. The workflow for such an approach is as follows:

- Use Multi-Source Data Fusion: Enhance your model's input features. Instead of relying solely on drug chemical structures, incorporate additional data such as:

Table 2: Performance of DDINet for Mechanism-Wise DDI Prediction [15]

| Mechanism | Training Loss | Validation Loss | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excretion | 0.1443 | 0.3276 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Absorption | 0.1504 | 0.1503 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Metabolism | 0.4428 | 0.4600 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Excretion Rate (Higher Serum) | 0.0691 | 0.0778 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Average | - | - | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Molecular Design Using a Deep Learning-Guided GA

This protocol is adapted from the evolutionary design method that uses deep learning to guide a genetic algorithm, effectively navigating around local optima [17].

Objective: To evolve a seed molecule to optimize a specific property (e.g., light-absorbing wavelength) while maintaining chemical validity.

Materials:

- Seed Molecule: Starting compound in SMILES format.

- Encoding Function: Function to convert a SMILES string into an Extended-Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) vector (e.g., using the RDKit library with a length of 5000).

- Decoding Function: A trained Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to convert an ECFP vector back into a valid SMILES string.

- Property Prediction Function: A trained Deep Neural Network (DNN) to predict the target property from an ECFP vector.

- Genetic Algorithm Framework: Software to perform mutation and crossover on ECFP vectors.

Procedure:

- Encoding: Transform the seed molecule

m0into its ECFP vectorx0. - Initial Population: Create a population of vectors

P0 = {z1, z2, ..., zL}by applying mutation operators tox0. - Decoding & Validation: Convert each vector

ziin the population into a SMILES stringmiusing the RNN decoder. Check the chemical validity of eachmi(e.g., using the RDKit library). - Fitness Evaluation: Predict the property

tifor each valid molecule using the DNN:ti = f(e(mi)). The fitness is based on how closetiis to the target value. - Selection & Evolution: Select the top-performing ECFP vectors as parents. Generate a new population

Pnby applying crossover and mutation to these parents. - Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 for a set number of generations or until a convergence criterion is met.

- Output: Select the best-fit molecule from the final generation.

Protocol 2: Assessing Local Optima in Optimization Problems

This protocol is based on an experimental study that analyzed the prevalence of local optima in complex synthesis problems [14].

Objective: To empirically determine the quality and distribution of local optima in a specific optimization problem relevant to your research (e.g., molecular docking score optimization).

Materials:

- A mathematical optimizer capable of local search (e.g., Sequential Least Squares Programming - SLSQP).

- A defined objective function and constraints for your problem.

Procedure:

- Problem Definition: Clearly define your optimization problem, including the design variables and constraints.

- Repeated Local Search: Run the SLSQP optimizer a large number of times (e.g., 500 repetitions), each time starting from a different, randomly generated initial solution.

- Solution Collection: Record the final objective value and the solution found in each run.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot a histogram of the final objective values.

- Analyze the distribution. A narrow distribution of high-quality results suggests that local optima are not a severe problem. A wide distribution with many poor results indicates a "needle-in-a-haystack" problem where the global optimum is hard to find.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Evolutionary Drug Discovery

| Item | Function | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| AutoGrow4 | An open-source genetic algorithm for de novo drug design and lead optimization. It uses reaction-based chemistry and docking to evolve molecules [13]. | http://durrantlab.com/autogrow4 |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Used for manipulating molecules, calculating fingerprints, and checking chemical validity [13] [17]. | https://www.rdkit.org |

| Gypsum-DL | Converts SMILES strings into 3D molecular models with alternate ionization and tautomeric states, preparing ligands for docking [13]. | http://durrantlab.com/gypsum-dl |

| ZINC15 Library | A curated database of commercially available chemical compounds. Used as a source for molecular fragments and seed compounds [13]. | https://zinc15.docking.org |

| Rcpi Toolkit | A tool for extracting biochemical features from drug molecules (e.g., from SMILES format) for use in machine learning models [15]. | https://github.com/nanxstats/Rcpi |

| DDI Datasets | Publicly available datasets of known drug-drug interactions, essential for training and validating DDI prediction models. | DrugBank, Kaggle [15] |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference in how these strategies avoid getting stuck in local optima?

Population-based global search strategies, like Genetic Algorithms (GAs), maintain a diverse pool of candidate solutions. This diversity allows them to explore different regions of the search space simultaneously. Even if one part of the population converges on a local optimum, other individuals can discover a path toward the global optimum. GAs specifically use genetic operators: crossover combines traits from different parents, potentially creating new, high-quality solutions, while mutation introduces random changes, helping the population escape the area of attraction of a local optimum [19] [20]. In contrast, single-solution local search strategies, like the elitist (1+1) EA, operate on one candidate at a time. They typically only accept moves that improve the solution. To escape a local optimum, they must rely on a single, often unlikely, mutation that jumps directly to a better region across a "fitness valley," which can be inefficient if the valley is wide [20].

2. My GA is converging too quickly to a sub-optimal solution. What parameters should I adjust?

Premature convergence often indicates a loss of genetic diversity. You can adjust the following parameters to promote more exploration [21]:

- Increase the Mutation Rate: A higher rate introduces more randomness, helping to break out of local optima. Typical values range from 0.001 to 0.1. For a binary chromosome, a starting point can be 1 / (chromosome length) [21].

- Increase the Population Size: A larger population naturally maintains more diversity. For complex problems, consider a size between 100 and 1000 individuals [21].

- Decrease the Selection Pressure: If using tournament selection, try reducing the tournament size. This makes it easier for less-fit individuals (which might carry useful genetic material) to be selected for reproduction [21].

- Review Crossover Rate: While a high rate (e.g., 0.8) is common, if it is too high, it can break down good solutions too quickly. Experiment with values between 0.6 and 0.9 [21].

3. How do I represent my problem for a Genetic Algorithm, and what crossover method should I use?

The representation, or "encoding," depends entirely on your problem:

- Binary Vector: Used for feature selection or the knapsack problem, where each gene indicates the presence (1) or absence (0) of an item [22].

- Permutation of Integers: Used for ordering problems like the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) or scheduling, where each gene represents a city or a task [23].

The crossover method should match your encoding:

- Single-Point Crossover: A crossover point is randomly selected, and the segments from two parents are swapped. Simple but can have positional bias [24].

- Two-Point Crossover: Two points are selected, and the segment between them is swapped. Reduces positional bias compared to single-point [24].

- Uniform Crossover: For each gene, the parent from whom it is inherited is chosen randomly based on a coin toss. This is highly explorative but may require modifications for problems like TSP to avoid illegal solutions (e.g., duplicate cities) [24].

- Order Crossover (OX): Designed for permutations. A subsequence from one parent is copied to the child, and the remaining genes are filled in the order they appear from the second parent, preserving the permutation property [23].

4. When should I choose a local search method over a global method like a GA?

Local search methods are often more suitable in the following scenarios [25]:

- The problem's fitness landscape is known to be convex or unimodal (free of significant local optima).

- You have a good initial solution from domain knowledge, and you need to refine it efficiently.

- Computational resources are extremely limited, as local search typically evaluates fewer solutions per iteration.

- The objective function is smooth and differentiable, making it amenable to efficient gradient-based methods.

For complex, multi-modal problems with a rugged landscape, or when you have little prior knowledge about where the optimum lies, a population-based global search like a GA is generally more robust [25].

Comparison of Search Strategies

The table below summarizes the core differences between the two search paradigms.

| Feature | Population-Based Global Search (Genetic Algorithm) | Single-Solution Local Search (e.g., (1+1) EA) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Mimics natural evolution using a population of solutions [23]. | Iteratively improves a single solution via local perturbations [20]. |

| Mechanism for Escaping Local Optima | Crossover & Mutation: Diversity in the population and random mutations allow exploration across the search space [20]. | Mutation Only: Relies on a single, large-effect mutation to jump to a better region [20]. |

| Key Strength | Robust exploration of complex, multi-modal search spaces; less dependent on initial guess [25]. | Can be very efficient for refining solutions in smooth, unimodal landscapes. |

| Key Weakness | Higher computational cost per generation; requires tuning of several parameters [22] [21]. | High risk of premature convergence to a local optimum, especially in rugged landscapes [19] [20]. |

| Performance on Fitness Valleys | Can traverse valleys by accepting temporary fitness decreases (non-elitism) or through recombination. Efficiency depends on valley depth [20]. | Must jump across the valley in a single mutation. Efficiency depends on valley length, and can be exponentially slow [20]. |

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Strategies on a Model Problem

This protocol outlines how to empirically compare a Genetic Algorithm against a local search algorithm using a model fitness landscape that contains a known "fitness valley."

1. Objective: To compare the efficiency and robustness of a GA and a (1+1) EA in finding the global optimum on a fitness function designed with a local optimum and a global optimum separated by a valley.

2. Model Fitness Function: A constructed "valley" function can be defined on a Hamming path (a path where solutions are Hamming neighbors). The function has the following characteristics [20]:

- Local Optimum: A point with high fitness.

- Valley: A sequence of points with lower fitness leading away from the local optimum.

- Global Optimum: A point with the highest fitness, located on the other side of the valley. The difficulty of the problem is tuned by the length (number of steps between optima) and depth (fitness drop in the valley) parameters.

3. Algorithms & Setup:

- Genetic Algorithm (Global Search)

- Encoding: Binary strings.

- Initialization: Randomly generated population.

- Selection: Tournament selection (e.g., size 3).

- Crossover: Single-point crossover with a rate of 0.8.

- Mutation: Bit-flip mutation with a rate of 0.05.

- Replacement: Generational with elitism (keep the best 1-2 individuals).

- (1+1) EA (Local Search)

- Initialization: A single random solution.

- Mutation: Each bit is flipped independently with a probability of (1/n) (where (n) is the chromosome length).

- Selection: Elitist. The offspring replaces the parent only if its fitness is better.

4. Measured Metrics:

- Success Rate: The proportion of independent runs in which the algorithm finds the global optimum.

- Mean Best Fitness: The average of the best fitness found across all runs after a fixed number of generations.

- Mean Time to Solution: The average number of function evaluations required to find the global optimum.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow and logical structure of the two contrasting search strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key components and their functions for implementing and analyzing search algorithms in optimization research.

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Fitness Function | The objective function that quantifies the quality of any candidate solution. It is the primary guide for the search process [23]. |

| Solution Encoding (Chromosome Representation) | The method for mapping a potential solution to a data structure (e.g., binary string, permutation) the algorithm can manipulate [22]. |

| Mutation & Crossover Operators | The "variation operators." Mutation introduces random changes for exploration, while crossover combines parent solutions to exploit good building blocks [22]. |

| Selection Mechanism | The strategy for choosing which solutions get to reproduce (e.g., Tournament, Roulette Wheel). It controls the selection pressure toward fitter solutions [21]. |

| Benchmark Problems with Known Optima | Well-understood test functions (e.g., NK landscapes, TSP instances) used to validate, compare, and tune algorithm performance [20]. |

| Performance Metrics | Quantitative measures like Success Rate, Mean Best Fitness, and Mean Evaluations to Solution used to compare algorithm performance objectively [20]. |

Evolving the Algorithm: Advanced Hybrid GA Methodologies for Biomedical Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my hybrid GA-SA model converging to a suboptimal solution too quickly? This is a classic sign of premature convergence, often caused by an imbalance between exploration (GA) and exploitation (SA). The SA component may be too weak, failing to adequately refine promising solutions found by the GA. To address this, you can intensify the local search by increasing the number of SA iterations applied to high-fitness individuals or by adjusting the SA cooling schedule to cool down more slowly, allowing for a broader search at higher temperatures [26].

Q2: How do I set the initial temperature for the Simulated Annealing component? A common and practical method is to calculate the initial temperature based on the initial population's diversity. One approach is to set the initial temperature ( T_0 ) to the difference between the highest and lowest penalty (or cost) values in the initial population generated by the genetic algorithm. This automatically scales the temperature to the specific problem instance [26].

Q3: What is a good stopping criterion for the hybrid algorithm? Multiple stopping criteria can be used in conjunction:

- Generation Count: A simple maximum number of generations.

- Solution Stagnation: Stop when the best solution has not improved for a predefined number of generations.

- Final Temperature: For the SA component, the process can stop when the temperature reaches a very low value ( ( T{final} ) ), where no further improvements are expected. One method to estimate this is ( Tf = \frac{Em - E{m'}}{\ln(\nu)} ) , where ( Em ) is the estimated global minimum, ( E{m'} ) is the next best cost value, and ( \nu ) is the number of moves between them [27].

Q4: How can I handle the high computational cost of the hybrid approach? The fitness evaluation (e.g., docking score in drug design) is often the bottleneck. Consider these strategies:

- Fitness Caching: Store and reuse fitness scores for identical individuals across generations.

- Initial Population Quality: Use chaotic maps or other methods to generate a high-quality, diverse initial population, which can lead to faster convergence [4].

- Adaptive Operator Rates: Dynamically adjust the rate of mutation/crossover based on population diversity to focus computational resources more effectively.

Q5: How do I decide between different neighborhood structures for the local search? The choice depends on your problem's solution representation. For permutation-based problems (like scheduling), you can implement multiple structures and select one randomly at each iteration [26]. Common structures include:

- Swap: Exchange two random elements in a solution sequence.

- Move/Relocate: Take one element and insert it at a different random position.

- Inversion: Reverse the order of a subsequence of elements. Using multiple structures helps prevent the search from getting stuck.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Final Solution Quality

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The algorithm consistently returns solutions that are significantly worse than known benchmarks or expected results. | - Weak Local Search: The SA component is not effectively exploiting the regions found by the GA.- Poor GA Exploration: The GA is not finding promising regions for SA to refine.- Overly Rapid Cooling: SA is quenching too fast. | - Intensify Local Search: Increase the number of SA iterations per individual [28].- Enhance GA Diversity: Introduce chaos-based initialization [4] or increase the population size.- Slower Annealing Schedule: Use a slower cooling rate (e.g., a higher value of ( r ) in ( T{new} = r \times T{old} ) ). |

Problem: Excessively Long Run Time

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The algorithm takes an impractically long time to reach a stopping criterion without a corresponding improvement in solution quality. | - Inefficient Fitness Function: The objective function is computationally expensive.- Overly Large Population/Generations.- Ineffective Local Search: SA is making too many non-improving moves. | - Optimize Code: Profile and optimize the fitness evaluation code.- Adjust Parameters: Reduce population size or maximum generations and increase elitism [13].- Tune SA Parameters: Increase the cooling rate or reduce the number of iterations per temperature level. |

Problem: Population Diversity Collapse

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The population becomes genetically homogeneous early in the run, halting progress. | - Over-Selection Pressure: The selection operator is too greedy.- Loss of Genetic Material: High mutation/crossover rates destroying good building blocks (dominant blocks). | - Use Less Greedy Selection: Implement tournament selection with a smaller tournament size [26].- Implement Dominant Block Mining: Use association rules to identify and protect high-quality gene combinations (building blocks) from being disrupted [4]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing a Basic HGASA for Scheduling

This protocol is adapted from a presentation scheduling problem, which is analogous to university course timetabling [26].

1. Solution Encoding:

- Encode the solution as a matrix (e.g., a slot-by-presentation matrix). A value of '1' indicates a presentation is assigned to a specific slot.

- This matrix serves as the chromosome in the GA and the candidate solution in SA.

2. Initialization:

- Generate an initial population of chromosomes randomly, ensuring no hard constraints (e.g., venue availability) are violated.

3. Genetic Algorithm Loop (Steady-State):

- Selection: Use tournament selection (size 2) to select parent chromosomes.

- Crossover: Perform two-point crossover on the parent matrices.

- Repair: Implement a repair function post-crossover to fix any violated hard constraints (e.g., two presentations in the same slot).

- Mutation: Swap the slots of two randomly selected presentations.

- Replacement: Replace the two worst chromosomes in the population with the two new children.

4. Simulated Annealing Local Search:

- Initial Candidate: Select the best solution from the GA population.

- Initial Temperature (( T_0 )): Set to the difference between the highest and lowest penalty in the GA population.

- Neighborhood Generation: Randomly apply one of several neighborhood structures to the current solution to create a neighbor. Examples include:

Neighbourhood Structure 1: Swap timeslots for two presentations with a common supervisor.Neighbourhood Structure 2: Change a presentation's venue, keeping time constant.Neighbourhood Structure 3: Move a presentation to a random empty slot.

- Acceptance Criteria: Always accept improving moves. Accept worsening moves with a probability of ( e^{(-\Delta E)/T} ), where ( \Delta E ) is the change in penalty cost.

- Cooling Schedule: Use an exponential cooling schedule: ( T{new} = r \times T{old} ), where ( r ) is a cooling rate (e.g., 0.85).

5. Termination:

- Stop after a fixed number of generations or when the SA temperature falls below a threshold.

Protocol: Hybrid GA for De Novo Drug Design (AutoGrow4)

This protocol outlines the hybrid GA used in AutoGrow4 for drug discovery, which incorporates elements of local search through its operators [13].

1. Solution Representation:

- Represent candidate drugs as SMILES strings.

2. Initial Population (Generation 0):

- Start with a set of seed molecules (e.g., molecular fragments for novel design or known ligands for lead optimization).

3. Population Generation Operators:

- Elitism: A subset of the fittest compounds from the previous generation advances unchanged.

- Mutation (Chemical Reaction): Perform an in silico reaction on a parent compound. One reactant is the parent, the other is from a library of small-molecule fragments (e.g., from Zinc15). This acts as a focused local search in chemical space.

- Crossover (Merger): Identify the largest common substructure between two parent compounds and generate a child by randomly combining their decorating moieties.

4. Fitness Evaluation:

- Docking: Use programs like AutoDock Vina to dock the 3D model of the compound into the target protein's binding site.

- Fitness Score: The primary fitness is the predicted binding affinity (docking score).

5. Selection:

- Compounds are selected for the next generation based on their fitness scores, guiding the search toward better-binding molecules.

Workflow and Algorithm Diagrams

HGASA High-Level Workflow

This diagram illustrates the overall flow of a typical Hybrid Genetic Algorithm with Simulated Annealing.

Simulated Annealing Local Search Process

This diagram details the inner loop of the Simulated Annealing component.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and concepts used in developing and implementing hybrid GA architectures.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Tournament Selection | A selection operator in GA that chooses the best individual from a small random subset of the population. This helps maintain selection pressure while preserving diversity [26]. |

| Two-Point Crossover | A crossover method where two points are selected in the parent chromosomes, and the segment between them is swapped. This helps preserve good building blocks (dominant blocks) better than one-point crossover [26]. |

| Exponential Cooling Schedule | A common method in SA to reduce temperature, defined by ( T{new} = r \times T{old} ), where ( 0 < r < 1 ). It provides a smooth and controlled transition from exploration to exploitation [26]. |

| Neighborhood Structures | A set of operations (e.g., swap, move, relocate) used in SA to generate new candidate solutions from the current one. Using multiple, randomized structures prevents search stagnation [26]. |

| Penalty Function | A function that quantifies constraint violations in a solution. It transforms a constrained optimization problem into an unconstrained one by adding a penalty to the fitness score for each violation [26]. |

| Chaotic Maps (e.g., Tent Map) | Used to generate the initial population for the GA. Chaos theory provides high diversity and ergodicity, improving the quality of the starting points and helping avoid premature convergence [4]. |

| Association Rules / Dominant Block Mining | A data mining technique used to identify and preserve high-quality gene combinations (building blocks) in high-fitness individuals. This reduces problem complexity and improves algorithmic efficiency [4]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. In drug-discovery GAs like AutoGrow4, it is used for critical operations like manipulating SMILES strings, performing crossovers, and applying molecular filters [13]. |

| AutoDock Vina | A widely used molecular docking program. It serves as the fitness function in structure-based drug design GAs by predicting the binding affinity of a generated compound to a target protein [13]. |

| Gypsum-DL | A software tool that converts 1D SMILES strings into 3D molecular models with optimized protonation, tautomeric, isomeric, and ring-conformational states. This prepares compounds for docking in a virtual screening pipeline [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is initial population diversity critical in Genetic Algorithms, and how does chaos theory help? Initial population diversity is a fundamental determinant for the global search capability of a Genetic Algorithm (GA). A diverse population helps in exploring different regions of the search space simultaneously, thereby reducing the probability of premature convergence on local optima [29] [30]. Chaos theory contributes through chaotic maps, which are deterministic systems that exhibit ergodicity, non-periodicity, and high sensitivity to initial conditions [31]. When used for population initialization, these maps can generate individuals that are spread more uniformly across the search space compared to purely random methods, providing a better foundation for the GA's exploration and exploitation phases [29] [32].

Q2: What are the specific drawbacks of the basic Tent Map that necessitate an "Improved" version? The basic Tent Map, while useful, has documented limitations that can affect the performance of the GA. Two primary drawbacks are:

- Finite Precision and Short Periods: When implemented on digital computers with finite precision, the basic Tent Map can suffer from short cycle lengths and degenerate into periodic orbits, which undermines the desired randomness and diversity [33] [34].

- Undesirable Fixed Points: The map can fall into "annulling traps" or "fixed points" (e.g., converging to zero), especially at specific parameter values, which stalls the sequence generation [33]. Improved versions, such as the Modified Skew Tent Map (M-STM), incorporate perturbations or other functions (like the sine function) to overcome these traps, resulting in a wider chaotic range and higher sensitivity, which in turn enhances the quality of the generated sequences [33].

Q3: My GA with chaotic initialization is converging rapidly but to a sub-optimal solution. What might be going wrong? Rapid convergence to a sub-optimal solution often indicates a loss of diversity in the early generations. While chaotic initialization provides a superior starting point, your other genetic operators might be too aggressive. Consider the following:

- Review Selection Pressure: If your selection operator is too strong (e.g., always selecting only the very best individuals), it can quickly eliminate the diversity introduced by the chaotic initialization. Consider using selection strategies that preserve some less-fit individuals [35].

- Adjust Crossover and Mutation Rates: A very high crossover rate can lead to premature convergence by rapidly homogenizing the population. Conversely, a mutation rate that is too low cannot reintroduce lost diversity. Tuning these parameters is essential [35] [9]. You may also consider introducing a small adaptive chaotic perturbation after crossover and mutation to help the population escape local optima [29].

Q4: How do I validate that the chaotic sequence used for initialization has good statistical properties? The validity of a chaotic sequence is confirmed through both its dynamical properties and statistical test suites.

- Dynamical Analysis: Plot the bifurcation diagram to visualize the map's behavior across different parameter values, confirming it remains chaotic and does not have large periodic windows. Calculate the Lyapunov Exponent (LE); a positive and large LE indicates high sensitivity to initial conditions and strong chaotic behavior [33].

- Statistical Testing: Use standardized test batteries like the NIST SP 800-22 suite to evaluate the randomness of the generated number sequence. A well-designed chaotic PRNG should pass a high percentage of these tests [33] [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Premature Convergence Despite Chaotic Initialization

Symptoms: The algorithm's fitness improves very quickly and then stalls. The population's individuals become very similar to each other within a few generations, and no significant improvements are observed thereafter.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Chaotic Map Performance | Verify that your Improved Tent Map has a positive and sufficiently large Lyapunov Exponent. Reject parameter values where the map exhibits periodic behavior [33]. |

| 2 | Audit Genetic Operators | Analyze the balance between your operators. Reduce selection pressure (e.g., use tournament selection instead of pure elitism for all individuals) and slightly increase the mutation probability to reintroduce diversity [35] [9]. |

| 3 | Implement Chaotic Perturbation | Introduce a small, adaptive chaotic perturbation to the population after standard genetic operations. This acts as a fine-tuning mechanism and can nudge the population out of local attractors [29]. |

| 4 | Hybridize with a Local Search | Consider a memetic algorithm approach. Use the GA for global exploration and employ a local search method (e.g., gradient-based, if applicable) for exploitation around promising solutions found by the GA. |

Problem: Degenerate Chaotic Sequences

Symptoms: The initial population lacks diversity. The chaotic map sequence gets stuck at a fixed point or enters a short, repeating cycle.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Parameter Values | Ensure the control parameter of the Tent Map is within its chaotic range. Avoid values that are known to cause periodic behavior or convergence [32]. |

| 2 | Introduce a Perturbation Mechanism | Switch to a proven Improved Tent Map. For example, use the Modified Skew Tent Map (M-STM) that incorporates a sine function and a perturbation term to prevent the sequence from falling into an annulling trap [33]. The mathematical form is: T(x,p) = { sin(( (1-p)/(1+p) - π*x/p ) * 10^5 ) for -1≤x<p; sin(( (1-p)/(1+p) - π*(1-x)/(1-p) ) * 10^5 ) for p<x≤1 } |

| 3 | Use High-Precision Data Types | Implement the chaotic map using high-precision floating-point arithmetic (e.g., double or higher) to mitigate the effects of finite precision in digital computers that lead to short cycles [34]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Initializing a GA Using an Improved Tent Map

This protocol details the steps to generate an initial population for a GA using the Improved Tent Map.

Workflow Diagram: Chaotic Population Initialization

Materials and Reagents:

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Improved Tent Map (e.g., M-STM [33]) | The core chaotic function used to generate a pseudo-random, ergodic sequence for sampling the search space. |

| Initial Seed (x₀) | The starting point for the chaotic map; small changes here produce vastly different sequences due to sensitivity. |

| Control Parameter (μ/p) | A parameter value that keeps the map in a chaotic regime, ensuring non-periodic and complex output. |

| High-Precision Arithmetic Library | Software/hardware support for high-precision calculations to prevent numerical degradation of the chaotic sequence. |

Methodology:

- Define Solution Space: Identify the boundaries and dimensions of the problem you are optimizing.

- Configure Chaotic Map: Select an Improved Tent Map (e.g., M-STM) and set its parameter

pto a value within the chaotic region (e.g., 0.4) [33]. - Initialize Sequence: Choose a random initial seed

x₀within the map's domain (e.g., [0, 1]). - Generate Sequence: Iterate the chaotic map to produce a long sequence of values:

xₙ₊₁ = T(xₙ, p). - Scale Values: Map each value from the chaotic sequence to a valid value within your solution space. For example, if optimizing a variable

zin [Zmin, Zmax], calculate:z = Z_min + xₙ * (Z_max - Z_min). - Construct Individuals: Use the scaled values to build the chromosomes of the initial population until the desired population size is reached.

Protocol 2: Comparing Chaotic Maps for Initialization

This protocol outlines a benchmark experiment to compare the performance of different chaotic maps for population initialization.

Workflow Diagram: Performance Comparison Experiment

Quantitative Data from Literature: Table 1: Comparison of Chaotic Map Properties [33]

| Chaotic Map | Key Characteristic | Lyapunov Exponent (Typical) | Known Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Map | Simple, widely studied | ~0.69 (for r=4) | Narrow chaotic parameter range, "high sides and low middle" distribution [32] |

| Basic Tent Map | Piecewise linear, uniform ideality | Sensitive to parameters | Vulnerable to annulling traps and finite precision effects [33] |

| Modified Skew Tent Map (M-STM) | Sine-modified, perturbed | >1.0 (higher is better) | Wider chaotic region, overcomes fixed points, higher computational cost [33] |

Table 2: Performance of GA with Chaotic Initialization on Benchmark Problems

| Application Domain | Algorithm | Key Performance Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Function Optimization | GA with Chaotic Crossover | Leads to more efficient computation compared to traditional GA | [36] |

| Facility Layout Optimization | Chaos GA (Improved Tent Map) | Enhanced initial population quality/diversity; superior in accuracy and efficiency | [29] |

| Solving Nonlinear Systems | Chaotic Enhanced GA (CEGA) | ~76% average improvement, faster convergence, prevents solution repetition | [31] |

| Traveling Salesman Problem | GA with Heuristic Seeding | Heuristic (non-random) initialization results in faster convergence to better solutions | [30] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental advantage of RGA over traditional Genetic Algorithms in SBDD? Traditional GAs rely on random-walk-like exploration for crossover and mutation, leading to unstable performance and an inability to transfer knowledge between different drug design tasks, despite the shared underlying binding physics. RGA uses neural models pre-trained on native complex structures to intelligently prioritize profitable design steps, suppressing this random behavior. This results in more stable optimization, better knowledge transfer, and ultimately, molecules with superior binding affinity [37] [38].

2. How does the Evolutionary Markov Decision Process (EMDP) reformulate the design process? The EMDP is a key innovation in RGA that reformulates the evolutionary process as a Markov Decision Process. Unlike traditional RL where the state is a single agent, in EMDP, the state is the entire population of molecules. This allows the neural policy to make decisions based on the collective state of the evolving solutions, guiding the population as a whole toward more promising regions of the chemical space [38].

3. My RGA is converging to suboptimal molecules. How can I improve the exploration of the chemical space? This issue, known as premature convergence, can be addressed by checking the following:

- Mutation Rate: Ensure your mutation rate is not too low. The mutation operation introduces random changes to an individual's policy (e.g., neural network weights) to maintain diversity. A typical mutation rate can be around 0.01 to 0.05 [39].

- Policy Network Pre-training: Verify that your neural models were properly pre-trained on diverse native complex structures. This pre-training equips the model with prior knowledge of binding physics, enabling more intelligent exploration from the start [37] [38].

- Population Diversity: Implement mechanisms like tournament selection to maintain a healthy level of diversity in your population, preventing early dominance by a single suboptimal solution [39].

4. What are the computational bottlenecks when running RGA on a new protein target? The primary bottlenecks are:

- Fitness Evaluation: Each call to the molecular docking oracle (e.g., Autodock, Vina) is computationally expensive. RGA improves sample efficiency, but docking remains the main cost [38] [40].

- Neural Model Inference: The forward passes of the 3D neural network to guide crossover and mutation add overhead, though this is typically less than the docking cost. Strategies to mitigate this include using a replay buffer to store and reuse past fitness evaluations, thus avoiding redundant oracle calls [41].

5. Can I use RGA for targets without a known 3D structure? RGA is explicitly designed for structure-based drug design (SBDD), meaning it requires the 3D structure of the target protein as input. If an experimental structure is unavailable, you might use a high-quality homology model predicted by tools like AlphaFold2, as the rise of accurate protein structure prediction has been a key driver for SBDD methods [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unstable Optimization Performance Between Independent Runs

Problem: Significant variance in final results (e.g., docking scores of best-designed molecules) when the RGA is run multiple times from different random seeds.

Diagnosis: This indicates that the algorithm is overly sensitive to initial conditions, a hallmark of the random-walk behavior that RGA aims to suppress. High variance between runs makes it difficult to trust the worst-case performance of the algorithm.

Solution:

- Verify Pre-training: Ensure your policy network was pre-trained on a diverse set of protein-ligand complexes. This provides a stable, knowledge-based foundation for the policy, reducing its reliance on random exploration [37].

- Check Fine-tuning: The policy should be fine-tuned during the optimization phase on the specific target. As the policy fine-tunes, it should become more specialized, leading to more stable and intelligent guidance in later stages. Empirical results show that variance should decrease after about 500 oracle calls [38].

- Adjust Selection Pressure: In your selection operator (e.g., tournament selection), a very small tournament size may not sufficiently select for good policies. Consider moderately increasing the tournament size to provide more consistent pressure toward high-fitness individuals [39].

Issue 2: Poor Sample Efficiency and Slow Convergence

Problem: The algorithm requires an excessively large number of expensive docking oracle calls to find a high-affinity ligand.

Diagnosis: The guidance from the neural policy is not effective enough, causing the algorithm to explore unpromising regions of the chemical space.

Solution:

- Implement a Replay Buffer: Integrate an experience replay buffer that stores past evaluations. When a molecule similar to a previously evaluated one is generated, the stored fitness can be reused, drastically reducing the number of calls to the docking oracle [41].

- Architecture Adaptation: Consider using a framework that dynamically adapts the neural network architecture guiding the search. Methods like ATGEN can trim the network to a minimal, effective configuration, leading to faster inference and convergence, and reducing computation during inference by over 90% [41].

- Hybrid Refinement: Introduce a local search mechanism. For instance, use a gradient-based method like backpropagation as a mutation operator to fine-tune the parameters (e.g., ligand conformations or policy weights) after crossover, leading to faster local convergence [41].

Issue 3: The Algorithm Gets Struck in Local Optima

Problem: The population's fitness stops improving early on, converging to a solution that is not globally optimal.

Diagnosis: The algorithm is exploiting a small region of the chemical space and lacks mechanisms to escape.

Solution:

- Knowledge Transfer: Leverage the pre-training of RGA on multiple targets. This "shared binding physics" knowledge helps the model generalize and avoid overfitting to a single task's local optima. Ablation studies show that training on different targets improves overall performance [37] [38].

- Dynamic Mutation Rates: Implement an adaptive mutation rate that increases if the population diversity drops below a certain threshold.

- Architectural Mutations: Beyond simple weight mutations, introduce operators that can modify the architecture of the policy network or the representation of the molecules themselves, allowing for more radical exploration. This is a feature of advanced neuroevolution techniques [41].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experiment: Optimization Performance on Diverse Disease Targets

Objective: To evaluate the binding affinity optimization performance of RGA against traditional and baseline methods across various disease-related protein targets.

Methodology:

- Target Selection: A set of disease targets with known 3D structures is selected.

- Baseline Algorithms: The following algorithms are compared:

- RGA (Proposed): The full Reinforced Genetic Algorithm with pre-training.

- RGA-pretrain: A variant without pre-training.

- RGA-KT: A variant without knowledge transfer (trained on a single target).

- Autogrow 4.0: A traditional genetic algorithm for molecular optimization [38].

- Graph-GA: A graph-based genetic algorithm.

- Evaluation Metric: The primary metric is the docking score, with results reported as TOP-K scores (e.g., TOP-100, TOP-10, TOP-1), which represent the best docking scores found in the top K molecules.

Results Summary (Structured Data): The following table summarizes the expected outcomes, based on published results. Lower (more negative) docking scores indicate tighter binding [38].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Optimization Algorithms in SBDD

| Algorithm | TOP-100 Score | TOP-10 Score | TOP-1 Score | Stability (Variance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGA (Proposed) | -10.2 ± 0.3 | -11.5 ± 0.4 | -12.8 ± 0.5 | Very Low |

| RGA-pretrain | -9.1 ± 0.6 | -10.3 ± 0.7 | -11.2 ± 0.8 | Medium |

| RGA-KT | -8.8 ± 0.8 | -9.9 ± 0.9 | -10.9 ± 1.0 | High |

| Autogrow 4.0 | -9.5 ± 1.2 | -10.8 ± 1.3 | -11.9 ± 1.4 | High |

| Graph-GA | -8.5 ± 1.0 | -9.5 ± 1.1 | -10.5 ± 1.2 | High |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the Reinforced Genetic Algorithm, highlighting how neural guidance is infused into the traditional evolutionary cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Resources for RGA Implementation in SBDD

| Category | Item / Software | Description & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Target Structure | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary source for obtaining 3D macromolecular structures of disease targets [40]. |

| Ligand Database | ZINC Database | Publicly available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening and initial population generation [40]. |

| Docking Software | Autodock, DOCK, GOLD | Programs used as the "oracle" for fitness evaluation, calculating the docking score (binding affinity) of a designed ligand [40]. GOLD specifically uses Genetic Algorithms. |

| 3D Neural Model | Policy Network | A neural model that takes 3D structures of the target and ligands as input. It is pre-trained on native complexes and fine-tuned during optimization to guide evolutionary operators [37] [38]. |

| Algorithmic Framework | RGA Codebase | The official implementation of the Reinforced Genetic Algorithm, typically provided in a GitHub repository (e.g., futianfan/reinforced-genetic-algorithm) [38]. |

| Fitness Function | Docking Score | A scoring function that approximates the binding free energy between a ligand and its target. This is the primary objective to minimize during optimization [37] [40]. |

Technical FAQ: Genetic Algorithm Implementation

Q1: Our genetic algorithm consistently converges to suboptimal solutions (local optima) when predicting AUC ratios. What strategies can help?

- A: Premature convergence is a common challenge. Implement the following strategies to enhance global search:

- Adaptive Chaotic Perturbation: Introduce small, adaptive chaotic perturbations to the best solution after crossover and mutation operations. This technique, inspired by improved Tent maps, helps kick the solution out of local optima without losing progress [4].

- Tournament Selection with Diversity: Use tournament selection with a carefully chosen tournament size (e.g., 15% of the population). This maintains a balance between exploitation (using good solutions) and exploration (searching new areas). A size that is too large leads to premature convergence, while one that is too small results in a random walk [42].

- Hybrid Approach: Combine the global search capabilities of the GA with a local search method for fine-tuning. Furthermore, use association rule theory to mine "dominant blocks" or high-quality gene combinations from the best individuals to guide the creation of new solutions, which reduces problem complexity [4].

Q2: How do we determine the optimal population size and number of generations to balance accuracy and computational cost?

- A: There is a critical trade-off between population size and the number of generations [43].

- Parameter Tuning is Key: Parameters like mutation probability, crossover probability, and population size must be tuned for the specific problem class. An excessively small population lacks diversity, while an overly large one wastes computational resources [9].

- Validation-Based Termination: A recommended approach is to use a population size that provides sufficient genetic diversity and terminate the algorithm based on a validation metric. Run the algorithm until the improvement in the highest ranking solution's fitness (e.g., prediction accuracy on a validation set) reaches a plateau over successive generations [9].

Q3: What is the recommended fitness function for evaluating predicted versus observed AUC ratios?

- A: The core of the GA is a fitness function that minimizes the difference between predicted and observed Area Under the Curve (AUC) ratios. A study successfully predicted AUC ratios within 50-200% of observed values by using a workflow that involved an initial parameter estimation via GA, followed by refinement using Bayesian orthogonal regression on all data. This two-step process enhances the robustness and accuracy of the final parameter estimates [44].

Troubleshooting Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Genetic Algorithm Workflow for DDI Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a GA to predict the extent of drug-drug interactions (DDIs), measured by the ratio of the victim drug's AUC with and without the perpetrator.

1. Problem Definition and Representation:

- Objective: Find the set of unknown parameters (e.g., fraction metabolized fm, inhibitory potency IC50) that best predict the observed clinical AUC ratios from DDI studies.

- Individual Representation: Encode the parameters to be optimized (e.g., CRCYP2C8, IRCYP2B6) into a "chromosome." This can be a real-valued array where each gene represents a parameter [44] [42].

2. Initialization: - Generate an initial population of candidate solutions (e.g., 100-1000 individuals) by randomly assigning values to the parameters within a physiologically plausible range [9].

3. Fitness Evaluation:

- Fitness Function: For each individual in the population, calculate the fitness. A common approach is to use an objective function that sums the squared differences between the predicted and observed AUC ratios for all DDIs in the training dataset [44]. A lower value indicates a better fit.

- Prediction Model: Use a pharmacokinetic model to generate the predicted AUC ratio. A standard model is the Rowland and Matin equation: AUC_ratio = 1 / [fm / (1 + [I]/Ki) + (1 - fm)], where [I] is the inhibitor concentration and Ki is the inhibition constant [45].

4. Selection: - Employ a selection method such as tournament selection to choose parents for the next generation. This involves randomly selecting a small subgroup from the population and choosing the fittest individual from that subgroup to be a parent, which helps maintain diversity [42].

5. Genetic Operators: - Crossover (Recombination): Recombine pairs of parent chromosomes to produce offspring. For real-valued representation, a common method is crossover split, where a random locus point is chosen, and segments of the parameter arrays are swapped between two parents [42]. - Mutation: Introduce random changes to a small proportion of genes in the new offspring (e.g., by adding a small random number to a parameter). This operator preserves population diversity and explores new regions of the solution space [9].

6. Termination and Validation: - Repeat steps 3-5 for multiple generations (e.g., 100-1000). Terminate the run when a stopping criterion is met, such as a maximum number of generations or a lack of significant improvement in fitness [9]. - Critical Step: Perform external validation using a separate, held-out dataset of clinical DDI studies not used during the optimization phase. This assesses the model's predictive performance and generalizability [44].

Protocol: In Vitro Reaction Phenotyping for CYP2C8 and CYP2B6

This protocol describes standard in vitro methods to characterize a drug's metabolism by specific CYP enzymes, which provides essential input parameters (like fm) for the GA model.

1. System Preparation: - Obtain in vitro systems: Human Liver Microsomes (HLMs) or a panel of cDNA-expressed recombinant CYP enzymes (rCYP) for CYP1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4 [45]. - Prepare incubation mixtures containing the enzyme source, cofactor (NADPH), and buffer.

2. Chemical Inhibition Assay: - Incubate the drug candidate (substrate) at a therapeutic concentration with HLMs in the presence and absence of selective chemical inhibitors. - Use montelukast as a selective CYP2C8 inhibitor [46] [45]. - Use (S)-(+)-N-3-benzyl-nirvanol or ticlopidine as a selective CYP2B6 inhibitor [45]. - Run control incubations with a non-selective inhibitor to define non-specific metabolism.