Harmonizing Genomic Medicine: Strategies to Resolve Interlaboratory Differences in Variant Interpretation

Inconsistent classification of genetic variants across clinical laboratories presents a significant challenge in genomic medicine, with reported discordance rates of 10-40%.

Harmonizing Genomic Medicine: Strategies to Resolve Interlaboratory Differences in Variant Interpretation

Abstract

Inconsistent classification of genetic variants across clinical laboratories presents a significant challenge in genomic medicine, with reported discordance rates of 10-40%. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework to understand, address, and minimize these inconsistencies. We explore the foundational causes of interpretation differences, detail established and emerging methodological standards from ACMG/AMP and ClinGen, and offer practical troubleshooting strategies for optimization. The content further covers validation techniques and comparative analyses of computational tools, culminating in a forward-looking synthesis that underscores the critical role of data sharing, gene-specific guidelines, and advanced bioinformatics in achieving reproducible and clinically actionable variant classification.

Understanding the Inconsistency Problem: Scope and Root Causes in Genomic Interpretation

Interlaboratory discordance—the variation in results when the same sample is analyzed by different laboratories—presents a significant challenge in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. This inconsistency can affect a wide range of fields, from genetic testing and cancer diagnosis to serology and neurobiology, potentially impacting research reproducibility, patient diagnosis, and treatment decisions. This guide quantifies the scope of this problem, presents key experimental data, and provides actionable troubleshooting protocols for researchers and scientists to identify, manage, and reduce discordance in their own work.

### FAQs: Understanding Interlaboratory Discordance

1. How common is diagnostic discordance in pathology? Studies reveal that initial diagnostic discordance can be surprisingly high. One investigation into breast pathology found that when comparing expert review with original database diagnoses, the initial overall discordance rate was 32.2% (131 of 407 cases). However, by applying a systematic 5-step framework to identify and correct for data errors and borderline cases, this discordance was reduced to less than 10% [1]. Another study focusing on breast cancer biomarkers (ER, PR, HER2, Ki-67) found pathological discordance rates ranging from 28% to 38.1% when comparing biopsies from the same patient under different conditions (e.g., pre- and post-chemotherapy, or between different institutions) [2].

2. What are the rates of discordance in genetic variant interpretation? Discordance is a recognized issue in clinical genetics. An initiative by the Canadian Open Genetics Repository (COGR) found that among variants classified by two or more laboratories, 34.4% had discordant interpretations when using a standard five-tier classification model (Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, VUS, Likely Benign, Benign). This discordance was significantly reduced to 29.9% after laboratories participated in a structured data-sharing and reassessment process. When viewed through the lens of clinical actionability (a two-tier model), the discordance was much lower, falling from 3.2% to 1.5% after reassessment [3]. A separate pilot of the ACMG-AMP guidelines showed that initial concordance across laboratories can be as low as 34%, though this can be improved to 71% through consensus discussions and detailed review of the criteria [4].

3. Which types of samples or tests are most prone to discordance?

Discordance is more likely in non-typical or borderline cases. In HER2 FISH testing for breast cancer, while overall agreement among laboratories can be substantial, cases with characteristics near the critical cutoff range or with genetic heterogeneity show significantly lower congruence, poorer reproducibility, and higher variability [5]. Similarly, in Alzheimer's disease biomarker research, a small but consistent percentage (around 6%) of patients show discordant results between cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and amyloid PET imaging, often associated with factors like APOE ε4 carriage and mixed or non-AD pathologies [6].

4. What are the primary causes of interlaboratory discordance? The causes are multifaceted and can include:

- Data Errors: Simple errors in data abstraction or entry can account for a portion of initial discordance. One study found that 2.9% of cases had data errors originating from the underlying registry, incomplete slides, or data abstraction [1].

- Interpretive Subjectivity: Differences in how pathologists or scientists interpret the same data or images is a key factor. One study concluded that the evaluating center and pathologist are important reasons for observed differences in breast biopsy immunohistochemistry [2].

- Pre-analytical and Analytical Variability: Differences in sample handling, reagents, assay conditions, and testing platforms contribute to variability. This is a noted issue in CSF biomarker analysis for Alzheimer's disease [6].

- Borderline Cases: Cases that naturally fall on the borderline between two diagnostic categories are a major source of disagreement. Among cases with clinically meaningful discordance, 53% were considered borderline [1].

- Evolution of Evidence and Guidelines: In genetics, classifications can change over time as new evidence emerges or guidelines are updated, leading to discordance if laboratories assess the same variant at different times [3].

### Quantitative Data on Discordance Rates

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings on interlaboratory discordance from recent studies.

Table 1: Diagnostic Discordance Rates in Pathology and Serology

| Field / Condition | Type of Test / Sample | Initial Discordance Rate | Discordance Rate After Review/QA | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Pathology [1] | Diagnostic categorization (benign, DCIS, invasive cancer) | 32.2% | < 10% | Data errors, borderline cases, interpretive variation |

| Breast Cancer Biomarkers [2] | IHC (ER, PR, HER2, Ki-67) between biopsies | 28.0% - 38.1% | Not Reported | Neoadjuvant therapy, tumor heterogeneity, evaluating center/pathologist |

| HER2 FISH Testing [5] | Gene amplification (all samples) | -- | Fleiss' κ: 0.765-0.911* | -- |

| HER2 FISH Testing [5] | Gene amplification (borderline/heterogeneous samples) | -- | Fleiss' κ: 0.582* | Lack of validation, lack of standard procedures, signals near cutoff |

| Serology [7] | ELISA re-testing | Variable (see example) | -- | Kit performance, laboratory quality |

*Fleiss' kappa is a statistical measure of inter-rater reliability where >0.8 is almost perfect agreement, 0.6-0.8 is substantial, and 0.4-0.6 is moderate.

Table 2: Discordance Rates in Genetic Variant Interpretation [3]

| Classification Model | Description | Baseline Discordance | Discordance After Reassessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Five-Tier Model | Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, VUS, Likely Benign, Benign | 34.4% | 29.9% |

| Three-Tier Model | Positive (P/LP), Inconclusive (VUS), Negative (LB/B) | 16.7% | 11.5% |

| Two-Tier Model | Actionable (P/LP), Not Actionable (VUS/LB/B) | 3.2% | 1.5% |

### Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide 1: A Framework for Evaluating Diagnostic Discordance in Research

This 5-step framework, adapted from a study on breast pathology, provides a systematic method to identify and address discordance uncovered during research activities [1].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Compare the Expert Review and Database Diagnoses: [1]

- Objective: To quantify the initial level of discordance.

- Action: Have an independent expert, blinded to the original diagnosis, review the source material (e.g., pathology slides, genetic data). Compare this expert diagnosis to the diagnosis recorded in your research database.

- Documentation: Carefully oversee research staff conducting these comparisons and document all findings.

Determine the Clinical Significance of Diagnostic Discordance: [1]

- Objective: To prioritize cases that require further investigation.

- Action: Categorize the discordance based on its potential impact. For example, would the different diagnoses lead to different treatment recommendations? Focus subsequent review on cases with "clinically meaningful" discordance.

- Documentation: Consult clinical experts as needed and document the rationale for significance categorizations.

Identify and Correct Data Errors and Verify True Diagnostic Discordance: [1]

- Objective: To distinguish true interpretive differences from simple data errors.

- Action: For discordant cases, go back to the original source data (e.g., original pathology reports, raw sequencing data). Check for abstraction errors, coding errors, or issues with sample quality/completeness.

- Documentation: Correct any data errors and document all changes. The remaining discordances are likely "true" interpretive differences.

Consider the Impact of Borderline Cases: [1]

- Objective: To understand how cases that naturally fall between categories affect discordance rates.

- Action: Review study documents to identify cases that were explicitly noted as borderline by either the original interpreter or the expert. Analyze the extent to which these cases contribute to the overall discordance.

- Documentation: Apply agreed-upon definitions for borderline cases and document their frequency.

Determine the Notification Approach for Verified Discordant Diagnoses: [1]

- Objective: To ethically manage the discovery of significant discordances that may impact past research or clinical care.

- Action: Consider the time lag since the original analysis and consult with experts in research ethics and relevant clinical fields to decide on a course of action, which may include notifying the original laboratory or facility.

- Documentation: Document all notification methods and practices.

Guide 2: Protocol for Handling Discordant and Equivocal Results in Serological Testing

This protocol provides a clear hierarchy for managing discordant or equivocal results from repeated testing, such as in seroprevalence studies. [7]

Experimental Workflow:

Re-test a Stratified Subset: Select a subset of specimens for re-testing that includes all equivocal results, a random subset of negative results, and a random subset of positive results from the first run. The second test can use the same kit or a different one, and may be performed in a different laboratory.

Construct a Concordance Table: Build a 3x3 table (Positive, Negative, Equivocal) comparing the results from the first and second runs to assess overall concordance.

Determine Overall Run Validity: If the concordance analysis shows a significant number of results that change categories (e.g., positive to negative), this casts doubt on the quality of the first run, and all specimens from that run should be re-analyzed.

Assign Final Outcome Values: For individual specimens with discordant results, follow a pre-specified hierarchy. An example hierarchy is:

- Use the results from the first run if its quality has been validated.

- Initial equivocal results may be replaced with positive or negative results obtained from a subsequent, validated run.

- For specimens that remain equivocal after re-testing, the study protocol must pre-specify how to categorize them (e.g., count as positive, count as negative, or maintain a separate category).

### The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials for Discordance Resolution in Genetic and Pathology Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Discordance Resolution | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Pathology Platforms [8] | Enables remote expert review, proficiency testing, and creation of permanent digital archives for re-evaluation, reducing slide handling damage and logistical issues. | National quality assurance programs in cytopathology using whole-slide imaging for diagnostic proficiency testing. |

| Variant Interpretation Platforms (e.g., Franklin by Genoox) [3] | AI-based tools that aggregate evidence from multiple sources and provide a suggested variant classification, facilitating comparison and consensus-building across laboratories. | Canadian Open Genetics Repository (COGR) using Franklin to identify and resolve discordant variant interpretations between labs. |

| Automated CSF Assay Platforms (e.g., Lumipulse) [6] | Reduce inter-laboratory variability by automating biomarker analysis, leading to higher consistency compared to manual ELISA assays. | Cross-platform comparison of Alzheimer's disease biomarkers (Aβ42, p-tau) to improve concordance with amyloid PET. |

| Standardized Antibody Panels [2] | Using validated, consistent antibody clones and staining protocols across laboratories minimizes a major source of technical variability in IHC. | Ensuring consistent staining for ER, PR, HER2, and Ki-67 in breast cancer biomarker studies. |

| Cell Line-Derived Quality Control Materials [5] | Provide homogeneous, well-characterized control materials with known results for proficiency testing and assay validation. | Using breast carcinoma cell lines (BT474, HCC1954) to create FFPE QC materials for HER2 FISH ring studies. |

FAQs: Understanding Interlaboratory Differences in Variant Interpretation

What are the main types of interpretation discrepancies?

Interlaboratory differences in variant classification are categorized by their potential impact on clinical management [9]:

- Five-tier class inconsistency: A difference among the five specific classification categories: Pathogenic (P), Likely Pathogenic (LP), Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS), Likely Benign (LB), and Benign (B).

- Three-tier class inconsistency: A difference among the three broader classification levels: P/LP vs. VUS vs. LB/B.

- Medically Significant Difference (MSD): A difference between actionable and non-actionable variants, specifically P/LP versus VUS/LB/B. This is the most critical type of discrepancy as it can directly influence patient care [9].

How prevalent are these inconsistencies?

Reported rates of interpretation differences vary, but studies highlight a significant challenge. The table below summarizes key findings from published literature [9].

| Study | Number of Variants | Disease Context | Initial Inconsistent Rate | Rate After Resolution Efforts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amendola et al., 2016 [9] | 99 | Unlimited | 66% (Five-tier) | 29% (Five-tier) |

| Garber et al., 2016 [9] | 293 | Neuromuscular, Skeletal | 56.7% (Five-tier) | Not Mentioned |

| Harrison et al., 2017 [10] | 6,169 | Unlimited | 11.7% (Three-tier) | 8.3% (Three-tier) |

| Amendola et al., 2020 [9] | 158 | 59 Genes | 16% (Five-tier) | Not Mentioned |

One multi-laboratory study found that 87.2% of discordant variants were resolved after reassessment with current criteria and internal data sharing, while 12.8% remained discordant primarily due to differences in applying the ACMG-AMP guidelines [10].

What core factors drive these discrepancies?

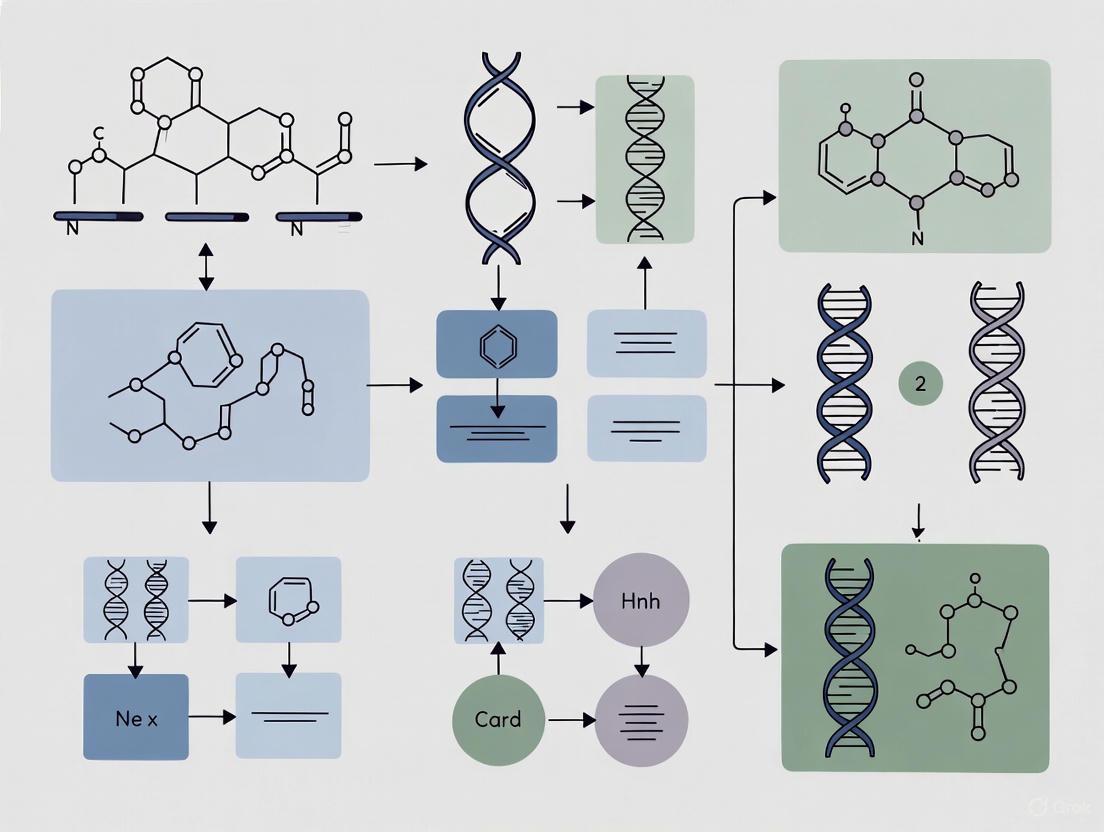

Discrepancies arise from multiple points in the interpretation workflow, illustrated in the following diagram.

Classification Methodology

Historically, many clinical laboratories developed their own in-house interpretation protocols, leading to inherent differences in classification pathways [9]. While the 2015 ACMG/AMP guideline standardized the framework, its design for broad adaptability means some criteria lack absolute precision. For example, laboratories may set different thresholds for allele frequency when applying the "extremely low frequency" (PM2) criterion, such as 0.1%, 0.5%, or 1% [9].

Asymmetric Information

Differences in the information available to interpreters is a primary cause of discrepancies [9]. This includes:

- Analysis Timeframe: Laboratories analyzing the same variant at different times may have access to different versions of public databases and literature.

- Internal Data: Access to private, internal laboratory data, such as allele frequencies from internal cohorts or previously classified cases, is often not uniformly shared [10].

- Phenotypic Information: Accurate use of phenotype-specificity (PP4) criteria relies on comprehensive and accurate clinical information, which can be limited or atypical at the time of testing [9].

Discordant Evidence Application

Even with the same evidence, laboratories may apply the ACMG/AMP criteria differently. A key study found that for variants that remained discordant after reassessment and data sharing, the root cause was "differences in the application of the ACMG-AMP guidelines" [10]. This reflects subjectivity in weighing and combining different types of evidence.

Subjective Expert Judgement

The ACMG/AMP guidelines require interpreters to combine multidimensional evidence with personal experience [9]. This necessary expert judgment introduces an inherent level of subjectivity, particularly when evidence is conflicting or novel scenarios are encountered.

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Variant Reassessment to Resolve Discrepancies

The following workflow, based on a successful multi-laboratory collaboration, provides a detailed methodology for identifying and resolving interpretation differences [10].

Key Procedures:

- Identification & Prioritization: Systematically compare variant classifications from multiple laboratories using a shared database like ClinVar. Prioritize reassessment based on clinical impact, focusing first on Medically Significant Differences (P/LP vs. LB/B), then on P/LP vs. VUS differences [10].

- Data Sharing and Documentation: For each prioritized variant, laboratories should confidentially share internal data (e.g., allele counts, co-segregation data, functional assay results) and fully document the initial rationale for classification, including the specific ACMG/AMP criteria used [10].

- Independent Reassessment: Each laboratory performs a new classification based on all pooled evidence and the current version of the ACMG/AMP guidelines. This step should be done independently before comparing results [10].

- Root Cause Analysis: For variants that remain discordant after reassessment, the specific points of disagreement in the application of the ACMG/AMP criteria must be identified and documented. This highlights areas where the guidelines may require further refinement or clarification [10].

The following tools and databases are essential for consistent and accurate variant interpretation.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Variant Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ACMG/AMP Guidelines [9] [10] | Interpretation Framework | Provides the standardized evidence-based framework for classifying variants into P, LP, VUS, LB, and B categories. |

| ClinVar [10] | Public Database | A central, public archive for submissions of interpreted variants, allowing for identification of interpretation differences between labs. |

| Population Databases (e.g., gnomAD) | Data Resource | Provides allele frequency data in healthy populations, critical for applying frequency-based criteria (e.g., PM2, BS1). |

| Internal Laboratory Database | Proprietary Data | Contains a laboratory's cumulative internal data on allele frequency and observed phenotypes, a common source of informational asymmetry [10]. |

| * Phenotypic Curation Tools* | Methodology | Standardized methods for capturing and relating patient clinical features to genetic findings, crucial for accurate PP4/BP4 application [9]. |

The Impact of Evolving Guidelines and Asymmetric Information

In genetic research, a critical challenge is the consistent classification of DNA variants across different laboratories. Interlaboratory variation in variant interpretation poses a significant barrier to reliable diagnostics and drug development. Differences in the application of evolving professional guidelines and asymmetric information—where one lab possesses data another does not—are primary drivers of these discrepancies. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to help researchers identify, troubleshoot, and resolve these issues, thereby enhancing the reproducibility and reliability of their findings.

The Scale of the Problem: Quantitative Evidence

Understanding the frequency and nature of interpretation differences is the first step in addressing them. The following table summarizes key findings from analyses of public variant databases.

| Metric | Findings | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Discordance Rate | 47.4% (2,985 of 6,292 variants) had conflicting interpretations [10]. | Variants interpreted by ≥2 clinical laboratories [10]. |

| Clinically Substantial Discordance | 3.2% (201 of 6,292 variants) had interpretations crossing the pathogenic/likely pathogenic vs. benign/likely benign/VUS threshold [11] [10]. | Conflicts with potential to directly impact clinical management [11]. |

| Discordance in Therapeutically Relevant Genes | 58.2% (117 of 201) of clinically substantial conflicts occurred in genes with therapeutic implications [11]. | Conflicts affect treatment decisions for conditions like epilepsy [11]. |

| Resolution through Data Sharing | 87.2% (211 of 242) of initially discordant variants were resolved after reassessment with current criteria and/or internal data sharing [10]. | Collaborative reanalysis demonstrated high resolvability [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Source of Interpretation Differences

Use this workflow to systematically identify the root cause of a variant classification discrepancy between your lab and an external source.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our lab has classified a variant as a "Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS)," but another reputable lab calls it "Likely Pathogenic." What immediate steps should we take?

A1: Follow this protocol:

- Contact the Other Laboratory: Initiate a direct dialogue to share the specific evidence and reasoning behind your respective classifications. This is the most effective first step [10].

- Conduct an Internal Reassessment: Re-evaluate the variant using the most current version of the ACMG/AMP guidelines and all available internal data.

- Share Internal Data Formally: If the discrepancy persists after initial discussion, propose a structured data sharing agreement. Collaborative studies have shown that sharing internal data (e.g., case observations, functional data) resolves a majority of interpretation differences [10].

- Submit to ClinVar: Report your final interpretation, along with supporting evidence, to the public ClinVar database. Note any discrepancies with other submitters to contribute to global resolution efforts [11] [10].

Q2: How can we proactively minimize interpretation differences when establishing a new testing protocol?

A2: Implement these practices from the outset:

- Adopt Latest Standards: Mandate the use of the most recent professional guidelines (e.g., current ACMG/AMP standards) and ensure all analysts are trained on their consistent application.

- Define a Data-Sharing Charter: For multi-center research, establish a pre-approved agreement for sharing internal variant data to reduce information asymmetry.

- Use Public Databases: Require that all variant interpretations and supporting evidence are submitted to ClinVar, fostering transparency and crowd-sourced peer review [10].

- Implement Periodic Review: Schedule regular re-analysis of variant classifications to incorporate new public evidence and evolving guidelines.

Q3: What is the role of regulatory guidelines and data standards in mitigating this problem?

A3: Evolving regulatory and data standards are crucial for creating a more transparent and consistent ecosystem.

- Clinical Trial Protocols: The updated SPIRIT 2025 statement emphasizes protocol completeness, including plans for data sharing and transparent description of methods, which underpins reproducible research [12].

- Data Standards: Regulatory bodies like the FDA require standardized data formats (e.g., CDISC standards) for submissions. Using these standards from the research phase improves data quality, traceability, and facilitates sharing and comparison across studies [13] [14].

- Real-World Evidence (RWE): Regulatory agencies are increasingly accepting RWE. Developing standards for incorporating RWE into variant interpretation can help resolve conflicts by providing additional, large-scale data points [15] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents, databases, and platforms are essential for conducting robust variant interpretation research and implementing the troubleshooting guides above.

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| ClinVar Database | Public archive of reports on the relationships between human variations and phenotypes, with supporting evidence. Used to compare your interpretations with other labs [11] [10]. |

| ACMG/AMP Guidelines | An evidence-based framework for classifying sequence variants into categories like "Pathogenic," "Likely Pathogenic," "VUS," "Likely Benign," and "Benign." Provides a standardized starting point for interpretation [10]. |

| CDISC Standards | Foundational and therapeutic area-specific data standards. Their use ensures data is structured consistently, which is critical for sharing, pooling, and comparing data across laboratories and for regulatory submissions [13] [14]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software for processing next-generation sequencing data, performing variant calling, and annotation. Standardized pipelines help reduce technical sources of variation before clinical interpretation. |

| Internal Laboratory Database | A curated, private database of a lab's own historical variant interpretations and associated patient and functional data. A key source of information that can create asymmetry if not shared [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Resolving a Specific Variant Interpretation Discrepancy

This detailed methodology is adapted from published collaborative efforts and provides a step-by-step guide for reconciling a specific variant interpretation difference between two or more laboratories [10].

Objective: To achieve consensus on the clinical classification of a specific genetic variant where interpretations between laboratories differ.

Materials:

- Variant of interest (e.g., GRCh38 genomic coordinates).

- Access to public data resources (ClinVar, gnomAD, PubMed, locus-specific databases).

- Access to internal laboratory data (case observations, functional data, family studies).

- Current ACMG/AMP classification guidelines and any relevant disease-specific modifications.

Procedure:

- Variant Identification and Initial Assessment:

- Identify the variant for which a interpretation discrepancy exists.

- Each laboratory involved should document their current classification and, critically, compile the complete evidence matrix used to reach that conclusion. This includes listing every ACMG/AMP criterion that was applied and its strength (e.g., PM1, PP3, BS1).

Blinded Evidence Comparison:

- In a structured meeting or exchange, the laboratories should share the types of evidence they considered (e.g., "we used population data from gnomAD," "we have two unrelated affected cases," "we applied the PP3 in-silico prediction criterion") without initially revealing the final calculated classification.

- This helps identify differences in the evidence base (information asymmetry) versus differences in how the same evidence was weighted.

Structured Data Sharing and Reassessment:

- Share any unique internal data (e.g., detailed clinical phenotypes of probands, segregation data, functional assay results) that was previously held by only one laboratory.

- Each laboratory then independently re-assesses the variant using the now-shared complete evidence set and the current ACMG/AMP guidelines.

Consensus Discussion:

- Compare the new, post-reassessment classifications.

- If discrepancies remain, focus the discussion on the specific ACMG/AMP criteria where application differs. For example, one lab may have applied a "Strong" (PS4) criterion for multiple observed cases, while another applied a "Moderate" (PM1) criterion for the same data.

- The goal is to understand the subjective differences in guideline application.

Finalization and Reporting:

- Document the final consensus classification, or agree to disagree and document the respective positions with clear rationales.

- Update internal laboratory databases.

- Submit the new interpretation(s) and the shared evidence that led to it to ClinVar. This closes the loop and informs the global community, preventing future redundant investigations [10].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Discordant Variant Classifications

Problem: Different laboratories classify the same sequence variant differently, leading to conflicting clinical reports.

Solution:

- Assemble a Multidisciplinary Committee: Form a variant interpretation committee (VIC) comprising clinical geneticists, molecular biologists, bioinformaticians, and pathologists [17].

- Adopt a Standardized Scheme: Implement a five-tier classification system (e.g., the IARC system endorsed by the Human Variome Project) [17].

- Define Rigorous Criteria: Establish transparent, evidence-based criteria for each classification tier. Require multiple lines of evidence, including clinical, genetic, and functional data, to support any classification [17].

- Aggregate Data via Microattribution: Use a centralized locus-specific database (LSDB) and encourage data submission through microattribution to credit contributors, which helps resolve classifications for variants with scarce data [17].

- Reach Consensus: Hold regular committee meetings to review evidence and assign a final consensus classification for each variant [17].

Guide 2: Addressing Failure to Meet Analytical Performance Requirements

Problem: Laboratory results for specific analytes do not meet the required performance standards (e.g., from the EU drinking water directive), leading to unreliable data [18].

Solution:

- Benchmark Current Performance: Participate in interlaboratory comparison or proficiency testing (PT) schemes to determine your current Coefficient of Variation (CV%) for the problematic analytes [18].

- Compare with Requirements: Contrast your laboratory's CV% with the maximum standard uncertainty permitted by the relevant regulation (see Table 1 for examples) [18].

- Identify Problematic Analytes: Focus improvement efforts on analytes where the average CV% in PT schemes consistently exceeds the maximum required standard uncertainty (e.g., Bromate, Cyanide, many pesticides, and PAHs) [18].

- Method Optimization: For identified problematic analytes, investigate and optimize the analytical method. This may involve using more specific instrumentation, improving sample preparation, or implementing stricter internal quality control measures [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the recommended framework for classifying sequence variants in a clinical research setting? The five-tier system developed by the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) is a robust model. This system, adapted from the IARC guidelines, classifies variants as: Pathogenic (Class 5), Likely Pathogenic (Class 4), Uncertain (Class 3), Likely Not Pathogenic (Class 2), and Not Pathogenic (Class 1) [17].

FAQ 2: How can we ensure our variant classifications are consistent with other laboratories? Consistency is achieved through collaboration and data sharing. Submit your variant data to public locus-specific databases (LSDBs) and participate in initiatives like the InSiGHT Variant Interpretation Committee, which provides expert-reviewed, consensus classifications for public use [17].

FAQ 3: For which types of analytical compounds is it most challenging to meet interlaboratory consistency requirements? Data from drinking water analysis shows that consistency is most difficult to achieve for certain trace elements (e.g., Aluminum, Arsenic, Lead), organic trace compounds (e.g., Benzene), and a significant majority of pesticides and their metabolites [18].

FAQ 4: What are the direct clinical implications of each variant classification class? The classification directly guides patient management:

- Classes 5 & 4: Predictive testing of at-risk relatives is recommended, and those who test positive should follow full high-risk surveillance guidelines [17].

- Class 3 (Uncertain): Predictive testing is not offered, and surveillance should be based on family history and other risk factors [17].

- Classes 1 & 2: Manage the patient and family as if "no mutation detected" for the specific disorder. Predictive testing is not recommended [17].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Example Interlaboratory Comparison Data for Drinking Water Analysis

This table, derived from proficiency testing (PT) results, compares the required maximum standard uncertainty from the EU drinking water directive with the average CV% observed in PT schemes, indicating where analytical quality consistently meets or fails requirements [18].

| Analyte Category | Example Analyte | Maximum Standard Uncertainty (%) | Average CV% in PT | Requirements Fulfilled? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Components | Nitrate | 8 | 4 | Yes [18] |

| Manganese | 8 | 9 | No [18] | |

| Trace Elements | Arsenic | 8 | 13 | No [18] |

| Copper | 8 | 5 | Yes [18] | |

| Volatile Organic Compounds | Benzene | 19 | 26 | No [18] |

| Chloroform | 19 | 15 | Yes [18] | |

| Pesticides | Atrazine | 19 | 17 | Yes [18] |

| Dimethoate | 19 | 42 | No [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Variant Classification Using the Five-Tier InSiGHT System

Objective: To consistently classify sequence variants in Mendelian disease genes for clinical reporting and research.

Methodology:

- Variant Curation: Collect all sequence variants and standardize nomenclature. Exclude somatic variants if the focus is on constitutional (germline) disease [17].

- Committee Review (Delphi Consensus Process): A multidisciplinary committee reviews all available evidence for each variant [17].

- Evidence Integration: Evaluate and weigh multiple lines of evidence, including:

- Population Data: Frequency in control populations.

- Computational/Predictive Data: In silico prediction scores.

- Segregation Data: Co-segregation with disease in families.

- Functional Data: Results from validated functional assays (e.g., for mismatch repair genes, this includes in vivo and in vitro assays of protein function) [17].

- Classification Assignment: Assign a final class (1-5) based on predefined criteria that translate the combined evidence into a posterior probability of pathogenicity [17].

- Data Dissemination: Update the locus-specific database with the consensus classification and all supporting evidence to ensure transparency [17].

Protocol 2: Assessing Analytical Performance via Interlaboratory Comparison

Objective: To evaluate a laboratory's analytical performance and measurement uncertainty against external standards and peers.

Methodology:

- Proficiency Testing (PT): Participate in a recognized PT scheme where all laboratories analyze the same homogenized sample material [18].

- Data Analysis by Organizer: The PT provider calculates robust summary statistics (e.g., using the Q-method as described in ISO/TS 20612:2007) from all participant results to determine the assigned value and the observed interlaboratory CV% [18].

- Performance Evaluation: The individual laboratory's result is compared to the assigned value. The standard uncertainty for the analyte is also evaluated against the required maximum standard uncertainty from the relevant directive (e.g., EU drinking water directive) [18].

- Trend Analysis: Monitor the laboratory's performance and the overall PT CV% over time to identify persistent issues with specific analytes and to gauge improvements in the field's analytical quality [18].

Mandatory Visualizations

Five-Tier Variant Interpretation Workflow

Interlaboratory Comparison Evaluation Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Variant Interpretation

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Locus-Specific Database (LSDB) | A curated repository (e.g., InSiGHT database hosted on LOVD) that aggregates variant data, evidence, and classifications from multiple sources, serving as the primary resource for consensus [17]. |

| Validated Functional Assays | In vivo or in vitro tests (e.g., for mismatch repair deficiency) that provide direct evidence of a variant's effect on protein function, a critical line of evidence for classification [17]. |

| Microattribution Identifiers (ORCID) | A system (e.g., Open Researcher and Contributor ID) used to provide credit for unpublished data submissions, incentivizing data sharing to resolve variants of uncertain significance [17]. |

| Proficiency Testing (PT) Scheme | An interlaboratory comparison program that provides homogeneous samples for analysis, allowing a lab to benchmark its analytical performance and uncertainty against peers and standards [18]. |

| Standardized Nomenclature (e.g., HGVS) | Guidelines for uniformly describing sequence variants, which is a foundational step to avoid confusion and ensure all data for a given variant is aggregated correctly [17]. |

Implementing Standardized Frameworks: ACMG/AMP Guidelines and Gene-Specific Specifications

FAQs on Implementation and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Our laboratory encounters frequent discordant variant classifications. What is the root cause of this inconsistency, and what evidence supports it?

A primary cause of discordance is the variable application and weighting of the 28 ACMG/AMP criteria across different laboratories. A key study evaluating nine clinical laboratories revealed that while the ACMG/AMP framework was compatible with internal methods (79% concordance), the initial inter-laboratory concordance using the ACMG/AMP guidelines was only 34% [19]. This significant variation stemmed from differences in how curators interpreted and applied the same evidence criteria to the same variants. After structured consensus discussions, concordance improved to 71%, demonstrating that increased specification and collaborative review are critical for improving consistency [19].

FAQ 2: How can we standardize the use of computational prediction tools to prevent poor-performing methods from overruling better ones?

A common pitfall is the guideline recommendation to use multiple prediction tools that must agree. This practice can allow lower-performing tools to negatively impact the overall assessment [20]. Benchmarking studies show that different computational predictors can disagree on a substantial portion of variants, with one analysis of nearly 60,000 variants showing 10%–45% of predictions were contradictory depending on the tools chosen [20].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Tool Selection: Do not rely solely on tools listed in older guidelines. Perform a systematic literature review to identify tools with state-of-the-art performance in independent benchmark studies like CAGI challenges [20].

- Avoid Redundancy: Select a limited number (e.g., one or two) of high-performance predictors that are not based on identical principles or training data to avoid bias [20].

- Expert Oversight: The choice of tools should be made by personnel with bioinformatics expertise who can interpret benchmarking results and understand the underlying methodologies [20].

FAQ 3: How should we adjust population frequency thresholds (BA1/BS1) for genes associated with different diseases?

The ACMG/AMP guideline provides a generic BA1 threshold (allele frequency >5%), but this is an order of magnitude higher than necessary for many rare Mendelian disorders [21]. Blindly applying this threshold can lead to misclassifying pathogenic variants as benign in high-penetrance genes.

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Calculate Gene-Specific Thresholds: Use the following formula to establish a more accurate, gene-specific threshold for your disease of interest [21]:

- Threshold = (Allowable Affected Frequency) / (Square root of Disease Prevalence)

- A conservative "Allowable Affected Frequency" is often set at 0.02 (2%).

- Use Filtering Allele Frequency (FAF): When querying population databases like gnomAD, utilize the provided Filtering Allele Frequency (FAF). This value represents the highest true population allele frequency for which the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval is still less than the variant’s observed count, functioning as a conservative lower-bound estimate [21].

- Consider Dataset Ascertainment: Understand the composition of your population dataset. For example, gnomAD primarily comprises adults, making it unlikely to contain many individuals with severe pediatric diseases, but it should not be considered a collection of "healthy controls" for adult-onset conditions [21].

FAQ 4: The "Pathogenic" and "Benign" classification seems like a false dichotomy for some genes. How can we handle genes where variants confer risk rather than cause disease?

This is a recognized limitation of the original guidelines, which were optimized for highly penetrant Mendelian disorders. For complex diseases or genes where variants act as risk factors, the five-tier system can be insufficient [22].

Expanded Framework Protocol: To address this continuum of variant effects, consider an adapted framework based on the gene's role in disease causation [22]:

- For "Disease-Causing Genes" (e.g.,

PRSS1in hereditary pancreatitis), use the standard five categories. - For "Disease-Predisposing Genes" (e.g.,

CFTR,CTRCin chronic pancreatitis), replace "Pathogenic" and "Likely Pathogenic" with the categories "Predisposing" and "Likely Predisposing" to more accurately reflect their role in disease risk [22]. This creates a five-category system better suited for multifactorial conditions.

Key Experimental Protocols for Addressing Interlaboratory Differences

Protocol 1: Conducting a Variant Classification Concordance Study

This protocol is based on the methodology used by the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) consortium to quantify inter-laboratory differences [19].

1. Variant Selection and Distribution:

- Select a set of variants (e.g., ~100) that span all five classification categories (Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, VUS, Likely Benign, Benign).

- Include a mix of variant types (missense, nonsense, indels) and difficulties.

- Designate a subset of variants (e.g., 9) to be interpreted by all participating laboratories to measure core concordance.

- Distribute the remaining variants so that each is interpreted by at least three different laboratories.

2. Independent Curation:

- Each laboratory classifies each variant using the ACMG/AMP guidelines.

- Laboratories must document every ACMG/AMP criterion (e.g., PM1, PS3, BP4) invoked for their decision.

3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate Concordance: Use statistical measures like Krippendorff’s alpha to quantify the level of agreement between laboratories, both on the final classification and the individual criteria used [19].

- Identify Discrepancies: Analyze variants with discordant classifications to pinpoint which criteria were applied differently.

4. Consensus Resolution:

- Convene discussions among laboratories to review discordant variants.

- Use the ACMG/AMP framework as a common language to debate the evidence and reach a consensus classification.

- Document the rationale for resolving each discrepancy to create a knowledge base for future guidance.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Quantitative Bayesian Framework

The ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) Working Group has developed a quantitative framework to refine the strength of ACMG/AMP criteria [21].

1. Assign Quantitative Odds:

- Use the SVI-estimated odds of pathogenicity for each evidence strength level [21]:

- Supporting (PP3, BP4): 2.08:1

- Moderate (PM1, PM4): 4.33:1

- Strong (PS2, PS3, BS2): 18.7:1

- Very Strong (PVS1): 350:1

2. Evaluate Functional Assays:

- For a functional assay used to apply the PS3 criterion, calculate the probability that a variant with a "damaging" result is truly pathogenic.

- If assessment indicates that ~90% of variants with damaging calls are truly pathogenic, the odds are ~9:1. Compare this to the quantitative scale: 9:1 odds fall between "Moderate" (4.33:1) and "Strong" (18.7:1), suggesting a "Moderate" strength level is appropriate rather than a "Strong" one [21]. This provides a data-driven method for assigning criterion strength.

Quantitative Data on Variant Interpretation Consistency

Table 1: Inter-laboratory Concordance in Variant Classification (CSER Study)

| Metric | Initial Concordance | Post-Consensus Concordance | Number of Laboratories |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACMG/AMP Guidelines | 34% | 71% | 9 [19] |

| Laboratories' Internal Methods | Information Missing | 79% ( Intra-lab ACMG vs. Internal Method) | 9 [19] |

Table 2: Quantitative Odds of Pathogenicity for Evidence Strength Levels (ClinGen SVI)

| Evidence Strength | Odds of Pathogenicity | Approximate Probability of Pathogenicity | Example ACMG/AMP Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting | 2.08 : 1 | 67% | PP3, BP4 |

| Moderate | 4.33 : 1 | 81% | PM1, PM4 |

| Strong | 18.7 : 1 | 95% | PS3, BS2 |

| Very Strong | 350 : 1 | >99% | PVS1 |

Table 3: Concordance in Application of Individual ACMG/AMP Criteria

| Study Description | Finding on Concordance | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Comparison of ACMG criteria selection across 36 labs [23] | Average concordance rate for individual criteria was 46% (range 27%-72%) | Highlights the subjective interpretation of when to apply specific criteria codes. |

Visualizing the Framework and Specification Process

ACMG/AMP Specification Workflow: This diagram outlines the process for creating gene or disease-specific specifications for the ACMG/AMP guidelines, moving from the generic rules to a calibrated and quantitative output [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Resources for ACMG/AMP Variant Interpretation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Variant Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) [21] | Population Database | Provides allele frequency data across diverse populations to assess variant rarity using metrics like Filtering Allele Frequency (FAF). |

| ClinVar [24] | Clinical Database | A public archive of reports on variant classifications and supporting evidence from multiple clinical and research laboratories. |

| Critical Assessment of Genome Interpretation (CAGI) [20] | Benchmarking Platform | Independent challenges that evaluate the prediction performance of computational tools, aiding in the selection of best-performing methods. |

| ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) WG [21] | Expert Consortium | Provides updated recommendations, specifications, and a quantitative framework for applying and evolving the ACMG/AMP guidelines. |

| ClinGen Variant Curation Expert Panels (VCEPs) [21] | Expert Committees | Develop and publish disease-specific specifications for the ACMG/AMP guidelines for specific gene-disease pairs (e.g., MYH7, FBN1). |

| dbNSFP / VarCards [20] | Prediction Aggregator | Databases that aggregate pre-computed predictions from numerous computational tools, streamlining the in-silico evidence collection process. |

| ACMG/AMP Pathogenicity Calculator [19] | Software Tool | Automated tools that help ensure evidence codes are combined according to the ACMG/AMP rules, reducing calculation errors during classification. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of interlaboratory differences in classifying variants in PALB2 and ATM? Interlaboratory differences primarily arise from the interpretation of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). The core challenge is the application of general guidelines, like the ACMG/AMP framework, to genes with unique functional characteristics without gene-specific refinement. For example, in PALB2, a missense variant in the coiled-coil domain may disrupt the BRCA1 interaction, while a variant in the WD40 domain may cause protein instability [25]. Without functional assays to distinguish these mechanisms, one lab might classify a variant based on computational predictions (e.g., PP3 evidence), while another might weight the lack of family segregation data (PP1) differently, leading to discrepant classifications [26].

FAQ 2: How can functional assays reduce classification discrepancies for PALB2 VUS? Functional assays provide objective, experimental evidence on a variant's impact on protein function, which is a strong (PS3) or supporting (PS1) evidence type in the ACMG/AMP framework. For instance, a cDNA-based complementation assay for PALB2 can directly test a variant's ability to rescue DNA repair defects in Palb2 knockout mouse embryonic stem cells [25]. Results from such semi high-throughput assays can definitively categorize VUS as either functionally normal or damaging. This replaces subjective interpretations with standardized, quantitative data—such as a variant's performance in Homologous Recombination (HR) efficiency relative to wild-type controls—directly addressing a major source of interlaboratory disagreement [25] [27].

FAQ 3: What are the key risk estimates for guiding the classification of pathogenic variants in PALB2 and ATM? Accurate risk estimates are crucial for calibrating the clinical significance of a variant. The table below summarizes key risk estimates from a large multicenter case-control study [28].

Table 1: Key Cancer Risk Estimates for Selected PALB2 and ATM Variants

| Gene | Variant | Cancer Type | Population | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PALB2 | c.1592delT | Breast | European women | 3.44 (1.39 to 8.52) | 7.1×10⁻⁵ |

| PALB2 | c.3113G>A | Breast | European women | 4.21 (1.84 to 9.60) | 6.9×10⁻⁸ |

| ATM | c.7271T>G | Breast | European women | 11.0 (1.42 to 85.7) | 0.0012 |

| CHEK2 | c.538C>T | Breast | European women | 1.33 (1.05 to 1.67) | ≤0.017 |

FAQ 4: Why is the ATM c.7271T>G variant classified as high-risk despite its wide confidence interval? The ATM c.7271T>G variant is classified as high-risk due to a very high point estimate (OR=11.0) and a statistically significant p-value (p=0.0012), even though its 95% confidence interval is wide (1.42 to 85.7) [28]. The wide interval reflects the variant's rarity, which makes precise risk estimation challenging with even large sample sizes. Such a significant result strongly indicates pathogenicity. Consistent with ACMG/AMP guidelines, this statistical evidence, combined with other data like its predicted loss-of-function mechanism, supports a Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic classification, prompting clinical actionability despite the statistical uncertainty [28] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Classification of Missense VUS in PALB2

Problem: Different laboratories are assigning conflicting clinical classifications (e.g., VUS vs. Likely Pathogenic) for the same missense variant in PALB2.

Solution: Implement a standardized functional assay workflow to generate objective, gene-specific evidence.

Step-by-Step Protocol: Functional Complementation Assay for PALB2 VUS [25]

Cell Line Preparation:

- Establish a mouse embryonic stem (mES) cell line with a knockout (KO) of the endogenous Palb2 gene. A Trp53 KO background can be used to facilitate cell viability [25].

- Integrate a DNA repair reporter system, such as the DR-GFP reporter, into this cell line to measure Homologous Recombination (HR) efficiency.

Vector Construction and Stable Expression:

- Clone the human PALB2 cDNA wild-type sequence into a Recombination-Mediated Cassette Exchange (RMCE) vector.

- Use site-directed mutagenesis to introduce the specific VUS into the PALB2 cDNA.

- Perform FlpO-mediated, site-specific integration of the wild-type and VUS PALB2 constructs into the Rosa26 locus of the Trp53KO/Palb2KO mES cells. Use a pooled population of neomycin-resistant clones to control for expression level variability.

Functional Analysis:

- HR Efficiency Assay: Transfert the DR-GFP reporter cells with an I-SceI endonuclease plasmid to induce a site-specific double-strand break. Measure HR efficiency by quantifying the percentage of GFP-positive cells using flow cytometry 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Additional Read-Outs (Optional):

- PARP Inhibitor Sensitivity: Expose cells to a PARP inhibitor (e.g., Olaparib) and perform a cell viability assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) after 5-7 days. Pathogenic variants confer hypersensitivity.

- G2/M Checkpoint Analysis: Irradiate cells and analyze the cell cycle profile via flow cytometry to assess checkpoint proficiency.

Data Interpretation and Classification:

- Normalize all HR efficiency results to the wild-type PALB2 control (set at 100%).

- Variants that rescue HR efficiency to levels statistically indistinguishable from wild-type (e.g., >70% of wild-type function) provide strong evidence for a benign impact (BS3 evidence).

- Variants that consistently fail to rescue the HR defect (e.g., <30% of wild-type function) provide strong evidence for a pathogenic impact (PS3 evidence).

This workflow for the functional complementation assay can be visualized as follows:

Issue 2: Translating Somatic Tumor Sequencing Findings to Germline Action

Problem: A potential pathogenic variant is identified in a tumor (somatic) sequencing report for ATM, and the clinical team is unsure whether to initiate germline genetic testing.

Solution: Follow a systematic workflow to evaluate the likelihood of a germline origin.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Variant Interpretation

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| DR-GFP Reporter | Measures repair of I-SceI-induced double-strand breaks via homologous recombination. | Quantifies functional impact of VUS in PALB2, ATM, and other HR genes [25]. |

| RMCE System | Enables site-specific, single-copy integration of cDNA constructs at a defined genomic locus. | Ensures consistent, comparable expression levels of wild-type and variant constructs, reducing experimental noise [25]. |

| Saturation Genome Editing (SGE) | CRISPR-Cas9-based method to test all possible SNVs in a gene domain for functional impact. | Generates high-throughput functional data for missense variants, resolving VUS at scale [27]. |

| VarCall Bayesian Model | A hierarchical model that assigns pathogenicity probability from functional scores. | Provides a standardized, statistical framework for classifying variants from MAVE data, reducing subjective interpretation [27]. |

| ClinVar Database | Public archive of reports on genomic variants and their relationship to phenotype. | Serves as a benchmark for comparing internal variant classifications with the wider community to identify discrepancies [26]. |

Evaluate the Somatic Variant:

- Check Variant Allele Frequency (VAF): A VAF around 50% (or 100% in a loss-of-heterozygosity region) in tumor DNA is suggestive of a germline origin. However, VAF can be confounded by tumor ploidy and purity.

- Review the Gene and Variant: ATM is an established hereditary cancer gene. Note the variant's type (e.g., nonsense, frameshift, missense) and its ACMG classification in ClinVar.

- Assess Tumor Type Concordance: Confirm that the cancer type (e.g., breast, pancreatic) is associated with germline ATM mutations [29] [30].

Make a Clinical Decision:

- If the somatic variant is a known Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic (P/LP) ATM variant: Refer the patient to a genetic counselor for discussion of confirmatory germline testing. This finding meets criteria for germline follow-up per recent guidelines [30].

- If the somatic variant is a VUS: The decision is more complex. If the variant has a high VAF and is a protein-truncating type, or if functional data (e.g., from a MAVE study) suggests pathogenicity, a genetics referral is still warranted. If evidence is weak, it may be prudent to monitor the variant's classification in databases.

Coordinate Germline Confirmation:

- Order germline genetic testing using a clinical-grade panel on a blood or saliva sample. A negative germline result confirms the variant was somatic-only, while a positive result identifies a heritable mutation with implications for the patient's therapy and family members [29].

The logical pathway for resolving a somatic finding can be summarized in this diagram:

FAQs: Resolving Common Data Interpretation Challenges

1. We observe conflicting variant classifications between databases. Which source should be prioritized for clinical decision-making?

Conflicting classifications between ClinVar and HGMD are common, with studies showing that ClinVar generally has a lower false-positive rate [31]. For clinical decision-making, prioritize variants with multiple submitters in ClinVar and those reviewed by ClinGen Expert Panels (displaying 2-4 stars in ClinVar's review status) [31] [26]. These represent consensus interpretations with higher confidence. HGMD entries, while useful for initial screening, should be corroborated with other evidence as they can imply disease burdens orders of magnitude higher than expected when tested against population data [31].

2. A variant is listed as disease-causing in HGMD but is present at a high frequency in gnomAD. Is this a misclassification?

This is a classic indicator of potential misclassification. A variant too common to cause a rare disease provides strong evidence for a benign interpretation [31] [24]. Use the following ACMG/AMP evidence codes:

- BS1 (Benign Strong): Allele frequency is greater than expected for the disorder [32] [26].

- PM2 (Pathogenic Moderate): Absent from or at extremely low frequency in population databases (supports pathogenicity) [32] [26].

Calculate whether the gnomAD allele frequency exceeds the expected disease prevalence. Reclassify the variant accordingly, giving greater weight to the population frequency evidence.

3. How can we systematically reduce Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in our pipeline?

High VUS rates, particularly in underrepresented populations, remain a major challenge [26]. Implement these strategies:

- Family segregation studies: Check if the variant co-segregates with disease in affected family members (ACMG/AMP code PP1) [26].

- Functional data integration: Incorporate validated functional studies (PS3/BS3 evidence) [26].

- Regular reanalysis: Schedule periodic reinterpretation (every 1-2 years) as new evidence emerges [24] [26].

- Data sharing: Contribute resolved cases to ClinVar to benefit the community [9].

4. Why does the same variant receive different classifications from different clinical laboratories in ClinVar?

Interlaboratory discordance affects approximately 10-40% of variant classifications [9]. Major causes include:

- Different thresholds for evidence: Laboratories may set different allele frequency cutoffs for ACMG/AMP criteria like PM2 [9].

- Asymmetric information access: Laboratories may have access to different in-house data or literature [9].

- Professional judgment differences: Application of criteria requires some expert judgment, leading to variability [9].

- Gene-specific knowledge: Genes with more exons, longer transcripts, and association with multiple distinct conditions show higher rates of conflicting interpretations [33].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Technical and Interpretation Challenges

| Challenge | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High False Positive Rate | Using outdated classifications; over-reliance on single evidence sources [31]. | Cross-reference HGMD “DM” variants with ClinVar and gnomAD; remove common variants (MAF > disease prevalence) [31]. |

| Population Bias in Interpretation | Underrepresentation of non-European ancestry in genomic databases [31] [26]. | Use ancestry-specific frequency filters in gnomAD; consult population-matched databases if available [31]. |

| Inconsistent ACMG/AMP Application | Subjectivity in interpreting criteria like PM2 (“extremely low frequency”) [9]. | Adopt ClinGen SVI specifications; use quantitative pathogenicity calculators [34]. |

| Variant Classification Drift | Knowledge evolution causing reclassification over time [31] [24]. | Implement automated re-evaluation protocols; track ClinVar review status updates [24]. |

| Handling Conflicting Evidence | Weighing pathogenic and benign evidence for the same variant [35]. | Use modified ACMG/AMP rules from ClinGen; prioritize functional evidence and segregation data [26]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Resolving Conflicting Variant Interpretations

Objective: Systematically resolve conflicts when ClinVar and HGMD provide discordant variant classifications.

Materials:

- Computer with internet access

- Variant identifier (RS number, HGVS nomenclature)

- Access to: ClinVar, gnomAD, HGMD (professional license recommended), UCSC Genome Browser

Procedure:

Initial Assessment

- Query the variant in both ClinVar and HGMD simultaneously

- Record all classification assertions and review status

- Note the number of submitters in ClinVar and their assertion criteria

Evidence Collection

- Population Frequency: Extract allele frequencies from gnomAD, noting ancestry-specific distributions

- Computational Predictions: Run multiple in silico tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD)

- Functional Evidence: Search for published functional studies in PubMed

- Segregation Data: Check for family studies in ClinVar submissions or literature

ACMG/AMP Criteria Application

- Use the ClinGen Pathogenicity Calculator or similar tool

- Apply disease-specific guidelines if available from ClinGen Expert Panels

- Document each evidence code with strength and direction

Adjudication

- Give greater weight to evidence from multiple independent submitters

- Prioritize functional evidence over computational predictions

- Consider disease mechanism and gene constraint (LOEUF scores from gnomAD)

Documentation and Submission

- Document the final classification and supporting evidence

- Consider submitting novel interpretations to ClinVar

- Update internal databases with resolution date and criteria

Troubleshooting:

- If evidence remains truly conflicting, maintain VUS classification

- For novel variants without functional data, pursue targeted functional assays

- For common conflicts in specific genes, consult relevant ClinGen Expert Panel

Systematic workflow for resolving conflicting variant interpretations between databases

| Resource | Function & Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| gnomAD Browser | Population frequency reference for assessing variant rarity and common polymorphisms [24]. | Ancestry-specific allele frequencies; constraint scores (LOEUF); quality metrics [36]. |

| ClinVar | Public archive of variant interpretations with clinical significance [31]. | Multiple submitter data; review status stars; linked to ClinGen expert panels [37]. |

| HGMD Professional | Catalog of published disease-associated variants from literature [31]. | Extensive literature curation; mutation type annotation; disease associations. |

| ClinGen Allele Registry | Variant normalization and identifier mapping across databases [34]. | Canonical identifiers; cross-database querying; API access. |

| Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | Functional consequence prediction of variants [33]. | Multiple algorithm integration; regulatory region annotation; plugin architecture. |

| ClinGen Pathogenicity Calculator | Standardized ACMG/AMP criteria implementation [34]. | Quantitative evidence scoring; ClinGen SVI guidelines; documentation generation. |

Key Methodologies from Recent Studies

Quantifying Database Accuracy Improvements Over Time

A 2023 study in Genome Medicine established a methodology to track variant classification accuracy by using inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) as a model system [31]. Researchers analyzed samples from the 1000 Genomes Project to identify individuals with genotypes classified as pathogenic in ClinVar and HGMD archives. Due to the rarity of IEMs, nearly all such classified pathogenic genotypes in this generally healthy population indicate likely variant misclassification [31]. The key metrics included:

- False-positive rate calculation: Comparing implied disease burden from database classifications against known disease prevalence

- Temporal analysis: Tracking reclassification rates over 6 years across different ancestry groups

- Ancestry bias assessment: Measuring differences in misclassification rates across global populations

Analysis of Conflicting Interpretations in ClinVar

A 2024 study systematically analyzed variants with conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity (COIs) in ClinVar [33]. The methodology included:

- Data extraction: ClinVar VCF files from April 2018 to April 2024, filtered for variants with COI status

- Gene enrichment analysis: Hypergeometric testing to identify genes with statistically significant COI enrichment

- Functional characterization: Gene Ontology and Human Phenotype Ontology analysis of COI-enriched genes

- Variant consequence analysis: Integration with gnomAD allele frequencies and Variant Effect Predictor annotations

This study found that 5.7% of variants have conflicting interpretations, with 78% of clinically relevant genes harboring such variants [33].

Leveraging Clinical Decision Support Software for Standardized Workflows

Clinical Decision Support (CDS) systems are designed to provide healthcare professionals with evidence-based information at the point of care. By integrating various inputs such as electronic medical record (EMR) data, clinical databases, external guidelines, and prediction algorithms, CDS delivers timely guidance to optimize decision-making [38]. For genomic medicine, where interlaboratory inconsistencies in variant interpretation present significant challenges, CDS offers a promising pathway toward standardization. These inconsistencies, with reported rates of 10-40% across laboratories, can lead to discrepant genetic diagnoses and affect clinical management decisions [9]. Implementing standardized CDS tools within variant interpretation workflows can help mitigate these discrepancies by ensuring uniform application of classification criteria across different laboratories and research settings.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our research team encounters inconsistent variant classifications when using different clinical databases. How can CDS help resolve this?

A: CDS systems can integrate multiple clinical databases through standardized application programming interfaces (APIs) like FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources). This provides a unified interface that reconciles differences according to predefined rules based on the 2015 ACMG/AMP guidelines. Ensure your CDS is configured to prioritize sources with the highest evidence levels and flag conflicts for manual review. Implementation of CDS Hooks allows for real-time consultation of external applications during EMR workflows, providing actionable guidance when discrepancies are detected [38].

Q2: We observe different interpretations of the ACMG/AMP PM2 criterion (allele frequency) across laboratories. How can CDS address this variability?

A: This is a common challenge as the ACMG/AMP guideline states "extremely low frequency" without specifying universal thresholds. Laboratories may set different allele frequency cutoffs (0.1%, 0.5%, or 1%). A CDS solution can standardize this by:

- Implementing configurable, institution-wide thresholds for population frequency data

- Applying natural language processing to latest literature for updated evidence

- Providing transparent documentation of criteria application for audit trails

- Regular synchronization with population databases like gnomAD to ensure current allele frequency data [9]

Q3: Our CDS system generates alerts that disrupt researcher workflow. How can we maintain support without creating interference?

A: This relates to the "Five Rights" of CDS framework - delivering the right information, to the right person, in the right format, through the right channel, at the right time [38]. To optimize:

- Implement passive alerts instead of interruptive pop-ups for non-critical information

- Use CDS Hooks to provide contextual suggestions without blocking workflow

- Customize alert thresholds based on variant criticality and research context

- Provide options for researchers to defer or customize notification preferences

Q4: How can we ensure our CDS system adapts to evolving variant classification evidence?

A: Configure your CDS for continuous learning through:

- Automated periodic reanalysis of variant classifications

- Integration with systems that monitor newly published literature

- Implementation of machine learning algorithms that incorporate updated clinical correlations

- Establishing protocols for manual review when automated systems detect significant evidence changes Regular synchronization with public databases like ClinVar ensures your system incorporates the latest community interpretations [9].

Troubleshooting Common Technical Issues

Problem: CDS tools fail to integrate with existing laboratory information systems.

- Solution: Verify compatibility with interoperability standards like SMART on FHIR, which establishes secure authentication and sharing of EMR context. Work with IT specialists to ensure proper API configuration and data mapping between systems [38].

Problem: Discrepancies between computational predictions and functional evidence in variant assessment.

- Solution: Implement a tiered evidence weighting system within your CDS that clearly distinguishes between computational predictions and functional validation data. Use the CDS to flag conflicts for prioritized expert review rather than automated resolution [9].

Problem: Researcher non-adherence to CDS recommendations.

- Solution: Investigate whether the issue stems from alert fatigue, lack of trust, or workflow disruption. Optimize using the "Five Rights" framework, provide education on the evidence base supporting recommendations, and solicit researcher feedback for system improvements [38].

Quantitative Data on Variant Interpretation Consistency

Reported Rates of Interlaboratory Variant Interpretation Inconsistency

Table 1: Summary of Variant Interpretation Inconsistency Rates from Published Studies

| Study | Number of Variants | Disease Context | Five-Tier Inconsistency Rate | Three-Tier Inconsistency Rate | Medically Significant Difference Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amendola et al., 2016 [9] | 99 | Unlimited | 66% → 29%* | 41% → 14%* | 22% → 5%* |

| Garber et al., 2016 [9] | 293 | Neuromuscular disorders, skeletal dysplasia, short stature | 56.7% | 33% | Not Mentioned |

| Furqan et al., 2017 [9] | 112 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Not Mentioned | 20.5% → 10.7%* | 17% → 9.8%* |

| Harrison et al., 2017 [9] | 6,169 | Unlimited | Not Mentioned | 11.7% → 8.3%* | 5% → 2%* |

| Amendola et al., 2020 [9] | 158 | 59 genes reported by accidental discovery | 16% | 29.8% → 10.8%* | 11% → 4.4%* |

Rates shown before and after reanalysis, data sharing, and interlaboratory discussion

Criticality Assessment Color-Coding System for Variant Interpretation

Table 2: Standardized Color-Coding for Assessing Variant Interpretation Criticality

| Color Zone | State of Criticality | Definition | Priority of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green [39] | Safe/Secure | Any hazards are controlled, latent, or undetectable | Proceed while avoiding known hazards |

| Amber [39] | Non-routine/Uncertain | Abnormality detected but unclear if represents imminent threat | Increase vigilance to trap and check deviations; proceed with caution |

| Red [39] | Critical | Clear and present danger identified, may already be causing harm | Make decisions to mitigate the threat |

| Blue [39] | Complex Critical | System unstable, harm evident and compounding | Immediate rescue action needed to avert irreversible outcome |

| Dark Grey [39] | Aftermath/Resolution | Situation has stabilized or progressed to final outcome | Reflect and learn from the outcome |

Experimental Protocols for Standardization

Protocol 1: Implementing CDS for Variant Interpretation Consistency

Objective: To integrate Clinical Decision Support tools into variant interpretation workflows to minimize interlaboratory discrepancies.

Materials:

- Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) with API capabilities

- CDS software with FHIR compatibility

- ACMG/AMP classification criteria database

- Curated variant database (ClinVar, lab-specific database)

- High-performance computing resources for analysis

Methodology:

- System Configuration:

- Map existing variant classification workflows to identify critical decision points

- Configure CDS to provide ACMG/AMP criteria suggestions at each decision point

- Establish standardized evidence thresholds for population frequency (PM2), computational predictions (PP3/BP4), and functional data (PS3/BS3)

Integration:

- Implement SMART on FHIR protocols for EMR integration

- Configure CDS Hooks for non-interruptive decision support during variant review

- Establish bidirectional data exchange between CDS and laboratory systems

Validation:

- Retrospectively analyze historical variant classifications with and without CDS

- Measure consistency rates between multiple reviewers using the same variants

- Compare classification outcomes with external references (ClinVar submissions)

Continuous Improvement:

Protocol 2: Resolving Discordant Variant Interpretations

Objective: To establish a standardized process for resolving variant interpretation discrepancies between laboratories.

Materials:

- CDS system with collaboration capabilities

- Secure data sharing platform

- Variant visualization tools

- Evidence curation dashboard

Methodology:

- Discrepancy Identification:

- Configure CDS to flag variants with conflicting interpretations between internal and external databases

- Implement automated alerts when new evidence contradicts existing classifications

Evidence Review:

- Use CDS to compile all available evidence for the discordant variant

- Apply standardized weighting to different evidence types following ACMG/AMP guidelines

- Utilize CDS-facilitated virtual review sessions with multiple laboratories

Consensus Building:

- Implement structured deliberation protocols within the CDS

- Document reasoning for classification decisions comprehensively

- Establish escalation pathways for unresolvable discrepancies

Resolution Implementation:

- Update classification in all connected systems simultaneously

- Document resolution rationale for future reference

- Communicate changes to all relevant stakeholders [9]

Workflow Visualizations

CDS-Enhanced Variant Interpretation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integration of Clinical Decision Support systems into the variant interpretation process, highlighting critical points where standardization reduces interlaboratory discrepancies.

CDS Standardization Mechanism: This visualization shows how Clinical Decision Support systems serve as a central standardization engine, processing diverse evidence sources to deliver consistent variant interpretations across different researchers and laboratories.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Tools for CDS-Enhanced Variant Interpretation Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Standardized Variant Interpretation

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SMART on FHIR API [38] | Enables secure integration of external applications with EMR systems | Requires compatibility with existing laboratory information systems; ensures secure authentication and data sharing |

| CDS Hooks [38] | Provides contextual suggestions at point of decision in workflow | Configurable to avoid alert fatigue; can be tailored to specific variant interpretation scenarios |