Penalty Functions in Optimization: Theory, Applications, and Advances for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of penalty function methods for solving constrained optimization problems, with a specialized focus on applications in drug discovery and development.

Penalty Functions in Optimization: Theory, Applications, and Advances for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of penalty function methods for solving constrained optimization problems, with a specialized focus on applications in drug discovery and development. It covers foundational principles, key methodological approaches including exact and quadratic penalty functions, and addresses practical challenges like parameter tuning and numerical stability. The content further explores advanced strategies for performance validation and compares penalty methods with alternative optimization frameworks, offering researchers and pharmaceutical professionals actionable insights for implementing these techniques in complex, real-world research scenarios.

Understanding Penalty Functions: Core Principles and Mathematical Foundations

What is the fundamental principle behind penalty methods?

Penalty methods are computational techniques that transform constrained optimization problems into unconstrained formulations by adding a penalty term to the objective function. This penalty term increases in value as the solution violates the problem's constraints, effectively discouraging infeasible solutions during the optimization process. The method allows researchers to leverage powerful unconstrained optimization algorithms while still honoring the original problem's constraints, either exactly or approximately.

In which research domains are penalty methods particularly valuable?

Penalty methods find extensive application in fields where constrained optimization problems naturally arise, including:

- Drug development and pharmacometrics: For computing optimal drug dosing regimens that balance efficacy and safety targets [1]

- Engineering design: For solving structural optimization problems with physical constraints

- Machine learning: For training models with specific requirements or limitations

- Optimal control theory: For solving control problems with state and control constraints [2]

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

How do penalty methods handle different types of constraints?

The approach varies based on constraint type, as summarized in the following table:

Table 1: Penalty Method Approaches for Different Constraint Types

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Form | Penalty Treatment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inequality | gⱼ(x) ≤ 0 | Penalizes when gⱼ(x) > 0 | Drug safety limits [1] |

| Equality | háµ¢(x) = 0 | Penalizes when |háµ¢(x)| > 0 | Model equilibrium conditions |

| State Constraints | g(y(t)) ≤ 0, t∈[tâ‚,tâ‚‚] | Penalizes violation over interval | Neutrophil level maintenance [1] |

What key terminology should researchers understand?

- Penalty Function (P): A function that measures constraint violation, typically zero when constraints are satisfied and positive when violated [1]

- Penalty Parameter (Ï): A weighting factor that determines the relative importance of constraint satisfaction versus objective optimization [1] [3]

- Feasible Solution: A solution that satisfies all constraints of the original problem

- Infeasible Solution: A solution that violates at least one constraint

- Exact Penalty Function: A penalty function that yields the same solution as the original constrained problem for finite values of the penalty parameter

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Basic Penalty Method Protocol

What are the systematic steps for implementing penalty methods?

- Problem Formulation: Begin by clearly defining the objective function and all constraints

- Penalty Function Selection: Choose an appropriate penalty function based on constraint types

- Parameter Initialization: Select initial penalty parameter values (typically starting with smaller values)

- Unconstrained Optimization: Solve the penalized unconstrained problem

- Parameter Update: Increase the penalty parameter according to a scheduled strategy

- Convergence Check: Verify if solution meets feasibility and optimality tolerances

- Solution Refinement: Continue iterating until satisfactory solution is obtained

Table 2: Penalty Function Types and Their Mathematical Forms

| Penalty Type | Mathematical Formulation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic | P(x,Ï) = Ï/2 × ∑[max(0,gâ±¼(x))]² | Smooth, differentiable | May require Ï→∞ for exactness |

| â„“â‚-Exact | P(x,Ï) = Ï Ã— ∑|háµ¢(x)| + Ï Ã— ∑max(0,gâ±¼(x)) | Finite parameter suffices | Non-differentiable at constraints |

| Exponential | P(x,Ï) = ∑exp(Ï×gâ±¼(x)) | Very smooth | Can become numerically unstable |

| Objective Penalty | F(x,M) = Q(f(x)-M) + ∑P(gⱼ(x)) | Contains objective penalty factor M [4] | More complex implementation |

Advanced Protocol: State-Constrained Optimal Control

How are penalty methods implemented for dynamic systems with state constraints?

For pharmacometric applications involving dynamic systems, researchers can implement the enhanced OptiDose protocol [1]:

Define the Pharmacometric Model: Formulate the system dynamics using ordinary differential equations: dy/dt = f(t,y(t),θ,D), y(t₀) = y₀(θ) where y represents model states, θ denotes parameters, and D represents doses [1]

Specify Therapeutic Targets: Define efficacy and safety targets mathematically:

- Efficacy: Typically expressed through cost function J(D) = ∫W(t,D)dt

- Safety: Usually formulated as state constraints N(t,D) ≥ threshold [1]

Formulate State-Constrained Optimal Control Problem: min J(D) subject to state constraints and bounds on D [1]

Apply Penalty Transformation: Convert to unconstrained problem using: min J(D) + P(D,Ï) where P(D,Ï) = Ï/2 × ∫[max(0,1-N(t,D))]²dt [1]

Implement in Software: Utilize pharmacometric software like NONMEM for solution

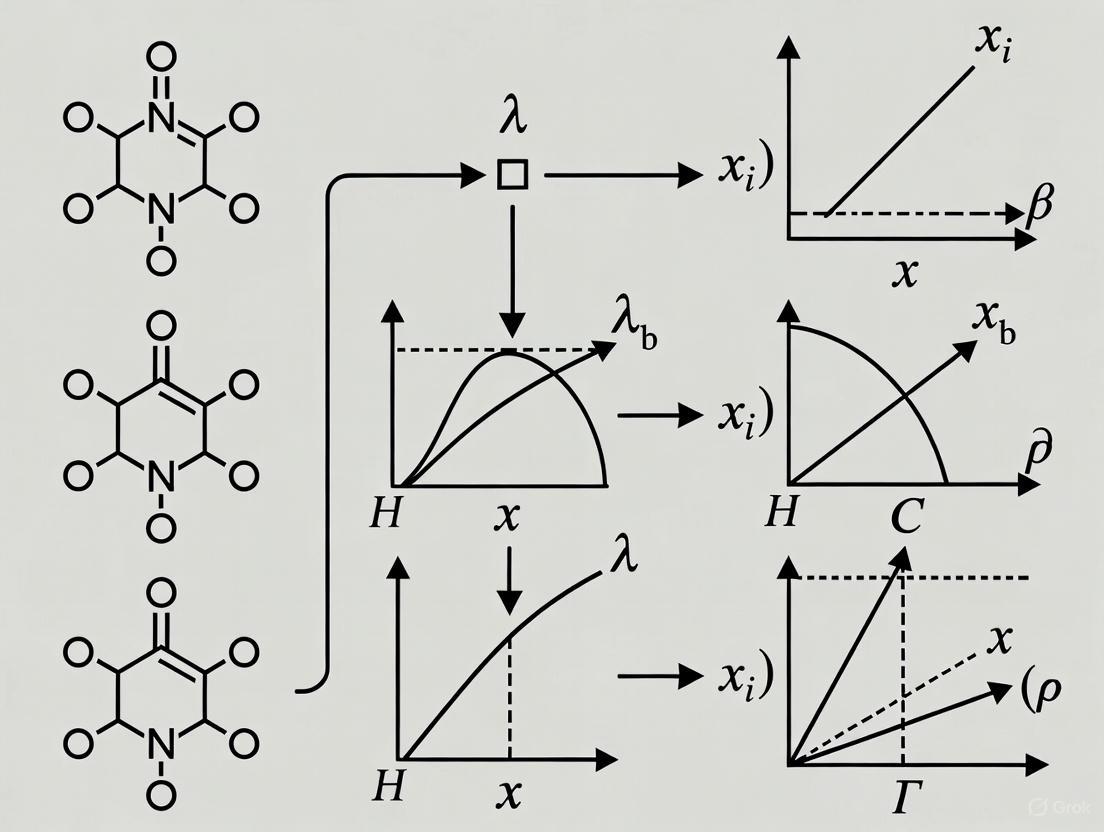

Diagram 1: Penalty Method Transformation Workflow (76 characters)

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Issues

Parameter Selection Problems

How should researchers select appropriate penalty parameters?

Table 3: Penalty Parameter Selection Guidelines

| Problem Type | Initial Value | Update Strategy | Convergence Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inequality Constraints | Ïâ‚€ = 1-10 | Ïâ‚–â‚Šâ‚ = 10×Ïâ‚– | max(gâ±¼(x)) ≤ ε₠|

| Equality Constraints | Ïâ‚€ = 10-100 | Ïâ‚–â‚Šâ‚ = 5×Ïâ‚– | |háµ¢(x)| ≤ ε₂ |

| Mixed Constraints | Ïâ‚€ = 10-50 | Adaptive based on violation | Combined tolerance |

What should I do if my solution remains infeasible despite high penalty parameters?

This common issue typically stems from:

- Insufficient penalty parameter magnitude: Systematically increase Ï until feasibility is achieved

- Numerical precision limitations: Implement exact penalty functions or smoothing techniques [5]

- Ill-conditioning: Use augmented Lagrangian methods for better conditioning

- Local minima: Employ global optimization strategies or multi-start approaches

Numerical Stability Issues

Why does my optimization fail when using very large penalty parameters?

Large penalty parameters create ill-conditioned optimization landscapes that challenge numerical algorithms. Address this by:

- Implementing smoothing techniques: Replace non-differentiable functions with smoothed approximations [5]

- Using exact penalty methods: These methods yield exact solutions for finite penalty parameters

- Applying homotopy methods: Gradually increase penalty parameters while using previous solutions as initial guesses

- Switching to specialized algorithms: Use methods specifically designed for penalized formulations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Penalty Method Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Software | NONMEM, MATLAB, Python SciPy | Solve unconstrained optimization problems | Pharmacometrics, general research [1] |

| Penalty Function Libraries | Custom implementations in C++, Python | Provide pre-coded penalty functions | Algorithm development |

| Modeling Environments | R, Julia, Python Pyomo | Formulate and manipulate optimization models | Prototyping and analysis |

| Differential Equation Solvers | SUNDIALS, LSODA, ode45 | Solve system dynamics in optimal control | Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models [1] |

Applications in Drug Development and Pharmacometrics

How are penalty methods applied to optimize drug dosing regimens?

In pharmacometrics, penalty methods enable computation of optimal drug doses that balance efficacy and safety:

- Define Dosing Scenario: Fix dosing times and optimize dose amounts D = (Dâ‚,Dâ‚‚,...,Dₘ) [1]

- Formulate Efficacy Target: Typically expressed as minimizing a cost function, e.g., J(D) = ∫TumorWeight(t,D)dt [1]

- Implement Safety Constraints: Represented as state constraints, e.g., N(t,D) ≥ 1 [1]

- Apply Penalty Transformation: Convert to unconstrained problem using penalty functions

- Compute Optimal Doses: Solve using appropriate optimization algorithms

What specific challenges arise when applying penalty methods to pharmacometric problems?

- Model complexity: Pharmacometric models often involve complex nonlinear dynamics

- Multiple constraints: Simultaneous handling of efficacy, safety, and practical constraints

- Parameter uncertainty: Model parameters may be estimated with significant uncertainty

- Clinical feasibility: Solutions must be practically implementable in clinical settings

Advanced Techniques and Recent Developments

What recent advancements address traditional penalty method limitations?

Recent research has developed enhanced penalty approaches:

- Smoothing â„“â‚-Exact Penalty Methods: Combine the exactness of â„“â‚ penalties with improved differentiability through smoothing techniques [5]

- Objective Filled Penalty Functions: Enable global optimization by systematically exploring better local minima [4]

- Adaptive Penalty Methods: Dynamically adjust penalty parameters based on convergence behavior

- Exponential Penalty Functions: Provide alternative formulations for optimal control problems [2]

Diagram 2: Penalty Method Iterative Algorithm (76 characters)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between penalty and barrier methods?

Penalty methods allow constraint violation during optimization but penalize it in the objective function, while barrier methods prevent constraint violation entirely by creating a "barrier" at the constraint boundary. Penalty methods can handle both equality and inequality constraints, while barrier methods are primarily for inequality constraints.

How do I know if my penalty function is working correctly?

Monitor these indicators during optimization:

- Consistent decrease in both objective function and constraint violation

- Progressive approach toward feasibility

- Stable convergence behavior

- Reasonable computation time

When should I use penalty methods instead of other constrained optimization approaches?

Penalty methods are particularly advantageous when:

- You have efficient unconstrained optimization algorithms available

- The problem has complex constraints that are difficult to handle directly

- You need to solve optimal control problems with state constraints [1]

- You're working with existing software that primarily supports unconstrained optimization

Can penalty methods guarantee global optimality for non-convex problems?

Traditional penalty methods cannot guarantee global optimality for non-convex problems. However, filled penalty functions [4] specifically address this limitation by helping escape local minima and continue searching for better solutions, potentially leading to global or near-global optima.

Foundational Concepts: FAQs on Penalty Methods and Constraint Violation

FAQ 1: What is a penalty function in the context of constrained optimization?

A penalty function is an algorithmic tool that transforms a constrained optimization problem into a series of unconstrained problems. This is achieved by adding a penalty term to the original objective function; this term consists of a penalty parameter multiplied by a measure of how much the constraints are violated. The solution to these unconstrained problems ideally converges to the solution of the original constrained problem [6].

FAQ 2: How is "constraint violation" quantitatively measured?

Constraint violation is measured using functions that are zero when constraints are satisfied and positive when they are violated. A common measure for an inequality constraint ( gj(x) \leq 0 ) is ( \max(0, gj(x)) ). The overall violation is often the sum of these measures for all constraints. For example, a quadratic penalty function uses ( \sum g( ci(x) ) ) where ( g(ci(x)) = \max(0, c_i(x))^2 ) [6]. In evolutionary algorithms and other direct methods, the Overall Constraint Violation (CV) is frequently calculated as the sum of the absolute values of the violation for each constraint [7].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between exterior and interior penalty methods?

The key difference lies in the approach to the feasible region and the behavior of the penalty parameter.

- Exterior Penalty Methods: These methods start from infeasible points (outside the feasible region). The penalty parameter is increased over iterations, drawing the solution toward feasibility from the outside. They are generally more robust [8].

- Interior Penalty (Barrier) Methods: These methods start from a feasible point and prevent the solution from leaving the feasible region. The penalty parameter is decreased to zero, allowing the solution to approach the boundary from the inside [6] [8].

FAQ 4: My penalty parameter is becoming very large, leading to numerical instability and slow convergence. What are my options?

This ill-conditioning is a known disadvantage of classic penalty methods [6]. Consider these alternatives:

- Augmented Lagrangian Method (ALM): This method incorporates Lagrange multiplier estimates in addition to the penalty parameter. This allows for convergence to the true solution without the penalty parameter going to infinity, thus avoiding much of the ill-conditioning [6].

- Filled Penalty Functions: For global optimization, advanced penalty functions with "filling" properties can help escape local optima without relying solely on an infinite penalty parameter [4].

FAQ 5: How do I handle uncertain constraints where parameters are not known precisely?

For problems with interval-valued uncertainties, a novel approach is to define an Interval Constraint Violation (ICV). This method classifies solutions as feasible, infeasible, or partially feasible based on the bounds of the uncertain constraints. A two-stage penalty function can then be applied, which tends to retain superior partially feasible and infeasible solutions in the early stages of evolution to promote exploration [9].

A Taxonomy of Penalty Functions: Measuring Violation

The following table summarizes common penalty functions and how they measure constraint violation.

Table 1: Common Penalty Functions and Their Properties

| Penalty Function Type | Mathematical Formulation (for min f(x) s.t. g_j(x) ≤ 0) | Measure of Violation | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic Penalty [6] | ( f(x) + p \sum \max(0, g_j(x))^2 ) | Squared violation | Exterior method. Simple, but requires ( p \to \infty ). |

| Log Barrier [8] | ( f(x) - r \sum \log(-g_j(x)) ) | Logarithmic of constraint value | Interior method. Requires initial feasible point. ( r \to 0 ). |

| Inverse Barrier [8] | ( f(x) + r \sum \frac{-1}{g_j(x)} ) | Inverse of constraint value | Interior method. Requires initial feasible point. ( r \to 0 ). |

| Objective Penalty [4] | ( Q(f(x) - M) + \rho \sum P(g_j(x)) ) | Separate functions ( Q ) and ( P ) for objective and constraints | Uses an objective penalty factor ( M ) in addition to a constraint penalty factor ( \rho ). |

| Filled Penalty [4] | ( H{\varepsilon}(x, \overline{x}, M, \rho) = Q(f(x)-M) + \rho \sum p{\varepsilon}(gj(x)) + \rho p{\varepsilon}(f(x)-f(\overline{x})+2\varepsilon) ) | Composite measure including distance from current local solution ( \overline{x} ) | Designed for global optimization. Helps escape local optima by "filling" them. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Algorithm Converges to an Infeasible Solution

- Potential Cause 1: The penalty parameter is not large enough to enforce constraint satisfaction.

- Solution: For exterior methods, systematically increase the penalty parameter ( p ) or ( \rho ) according to a schedule (e.g., multiply by 10 each iteration) [6] [8].

- Potential Cause 2: The algorithm is trapped in a local optimum of the penalized function.

- Solution: Consider using a filled penalty function that adds a term to help the search escape the basin of attraction of the current local solution [4].

Issue: Slow Convergence or Numerical Instability

- Potential Cause: The penalty parameter has become very large, making the Hessian of the penalized function ill-conditioned.

- Solution: Switch to the Augmented Lagrangian Method, which avoids the need for the penalty parameter to go to infinity [6]. Alternatively, use a more sophisticated unconstrained optimizer that can handle poor conditioning.

Issue: Handling a Mix of Relaxable and Unrelaxable Constraints

- Explanation: Unrelaxable constraints (e.g., physical laws) must be satisfied for a solution to be meaningful, while relaxable constraints (e.g., performance targets) can be slightly violated [7].

- Solution: Use a hybrid strategy. Apply an extreme barrier approach for unrelaxable constraints (assigning an infinite penalty if violated) and a standard penalty function for relaxable constraints. This prevents the waste of computational resources on physically meaningless solutions [7].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Quadratic Penalty Method

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for solving a constrained optimization problem using a basic quadratic exterior penalty method.

Objective: Minimize ( f(x) ) subject to ( g_j(x) \leq 0, j \in J ).

Materials & Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Penalty Method Experiments

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Unconstrained Optimization Solver (e.g., BFGS, Gradient Descent) | The core computational engine for minimizing the penalized objective function at each iteration. |

| Initial Penalty Parameter (( p_0 )) | A positive scalar value to initialize the penalty process. |

| Penalty Increase Factor (( \beta )) | A multiplier (e.g., 10) to increase the penalty parameter each iteration. |

| Convergence Tolerance (( \epsilon )) | A small positive scalar to determine when to stop the iterations. |

Methodology:

- Initialization: Choose an initial guess ( x^0 ), an initial penalty parameter ( p_0 > 0 ), a penalty increase factor ( \beta > 1 ), and a convergence tolerance ( \epsilon > 0 ). Set ( k = 0 ).

- Formulate Penalized Objective: Construct the quadratic penalized function: ( Q(x; pk) = f(x) + pk \sum{j \in J} \max(0, gj(x))^2 ) [6].

- Solve Unconstrained Subproblem: Using the unconstrained optimization solver, find an approximate minimizer of ( Q(x; p_k) ), starting from ( x^k ). Denote the solution as ( x^{k+1} ).

- Check for Convergence: Evaluate the maximum constraint violation: ( \text{violation} = \maxj \max(0, gj(x^{k+1})) ). If ( \text{violation} < \epsilon ), stop and output ( x^{k+1} ) as the solution.

- Update Parameters: Increase the penalty parameter: ( p{k+1} = \beta pk ). Set ( k = k + 1 ) and return to Step 2.

Diagram 1: Quadratic Penalty Method Workflow

Advanced Methodologies: Filled Penalty Functions for Global Optimization

For non-convex problems with multiple local minima, standard penalty methods may converge to a local solution. Filled penalty functions are designed to help find the global optimum.

Concept: A filled penalty function modifies the objective landscape not only by penalizing constraint violation but also by "filling" the basin of attraction of a local solution that has already been found. This allows the search algorithm to proceed to a potentially better local solution [4].

Experimental Workflow: The following diagram illustrates a typical algorithm using a filled penalty function to escape a local optimum and continue the search for a global one.

Diagram 2: Filled Penalty Global Search

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental concept behind a penalty method in constrained optimization?

Penalty methods are a class of algorithms that transform a constrained optimization problem into a series of unconstrained problems. This is achieved by adding a term, known as a penalty function, to the original objective function. This term consists of a penalty parameter multiplied by a measure of how much the constraints are violated. The measure is zero when constraints are satisfied and becomes nonzero when they are violated. Ideally, the solutions to these unconstrained problems converge to the solution of the original constrained problem [6].

Q2: What are the common types of penalty functions used in practice?

The two most common penalty functions in constrained optimization are the quadratic penalty function and the deadzone-linear penalty function [6]. Furthermore, the Lq penalty, a generalization that includes both L1 (linear) and L2 (quadratic) penalties, is used in advanced applications like clinical drug response prediction for its variable selection properties [10].

Q3: What is a major practical disadvantage of the penalty method?

A significant disadvantage is that as the penalty coefficient p is increased to enforce constraint satisfaction, the resulting unconstrained problem can become ill-conditioned. This means the coefficients in the problem become very large, which may cause numeric errors and slow down the convergence of the unconstrained minimization algorithm [6].

Q4: What are the alternatives if my optimization fails due to the ill-conditioning of penalty methods?

Two prominent alternative classes of algorithms are:

- Barrier Methods: These keep the iterates within the interior of the feasible domain and use a barrier to bias them away from the boundary. They are often more efficient than simple penalty methods [6].

- Augmented Lagrangian Methods: These are advanced penalty methods that allow for high-accuracy solutions without needing to drive the penalty coefficient to infinity, thereby avoiding the ill-conditioning issue and making the problems easier to solve [6].

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Poor Convergence or Numerical Errors

- Problem: The optimization algorithm converges very slowly, fails to converge, or produces

NaN/Infvalues. The solution seems to oscillate or diverge as the penalty parameter increases. - Cause: This is a classic symptom of an ill-conditioned problem, which occurs when using a simple penalty method and making the penalty parameter too large [6].

- Solution:

- Switch Methods: Consider using an Augmented Lagrangian Method instead of a basic penalty method. These methods are designed to avoid the ill-conditioning problem [6].

- Use a Sequence: If you must use a basic penalty method, implement a gradual increase of the penalty parameter. Do not start with an extremely large value. Solve the unconstrained problem for a moderate p, then use that solution as the initial guess for a new problem with a larger p.

- Robust Estimators: If your objective function or constraints are based on statistical models (e.g., in drug response prediction), consider using robust estimators (like MM-estimators) for parameters. These are less influenced by outliers, which can stabilize the optimization process [11].

Issue 2: Choosing the Right Penalty Constant

- Problem: The final solution is highly sensitive to the choice of the penalty constant, and there is no clear rule for selecting an appropriate value.

- Cause: A key drawback of some penalty methods, like the Penalty Function (PM) approach in dual response surface optimization, is the lack of a systematic rule for determining the penalty constant, leaving it to subjective judgment [11].

- Solution:

- Incorporate Decision Maker's Preference: Implement a systematic method like the Penalty Function Method based on the Decision Maker's (DM) preference structure (PMDM). This technique provides a structured way to determine the penalty constant ξ by formally incorporating the priorities of the decision maker, such as the relative importance of meeting a target mean versus minimizing variance [11].

- Cross-Validation: For data-driven problems, use techniques like cross-validation to evaluate the performance of different penalty constants on a validation dataset and select the one that provides the best, most stable performance.

Issue 3: Inaccurate Solution - Constraint Violation

- Problem: The optimization completes, but the solution violates one or more constraints beyond an acceptable tolerance.

- Cause: The penalty parameter is not large enough to sufficiently penalize the constraint violations, or the optimization was stopped before fully converging [6].

- Solution:

- Increase Penalty Parameter: Systematically increase the penalty parameter and re-run the optimization, using the previous solution as an initial guess.

- Use an Exact Penalty Function: Consider switching to an L1 (linear) exact penalty function. For a sufficiently large (but finite) penalty parameter, an exact penalty function can recover the exact solution to the constrained problem, whereas quadratic penalties only satisfy constraints in the limit as the parameter goes to infinity.

- Check Convergence Criteria: Tighten the convergence tolerances for the unconstrained solver to ensure it finds a true minimum for the penalized function.

Comparison of Common Penalty Functions

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary penalty forms discussed.

| Penalty Function | Mathematical Form (for constraint c(x) ≤ 0) | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages / Troubleshooting Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic (L2) | ( g(c(x)) = \max(0, c(x))^2 ) [6] | Smooth function, works well with gradient-based optimizers. | Not exact; can cause ill-conditioning with large p [6]. |

| Linear (L1) | ( g(c(x)) = \max(0, c(x)) ) | An "exact" penalty function; constraints can be satisfied exactly for a finite p. | Non-smooth at the boundary, which can challenge some optimizers. |

| Exact Penalty | Combines L1 penalty for constraints with a finite parameter. | Exact solution for finite penalty parameter; avoids ill-conditioning. | Requires careful selection of the single, finite penalty parameter. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Penalty Constant Determination

This protocol outlines the methodology for determining an effective penalty constant using the PMDM approach, as applied in dual response surface optimization [11].

Problem Formulation:

- Define your primary objective function (e.g., process mean, (\hat{\mu}(x))) and standard deviation function ((\hat{\sigma}(x))).

- Set the target value, (T), for the primary objective.

Define Decision Maker's Preference:

- Elicit from the decision maker the acceptable trade-off between bias (deviation from target) and variance. For example, determine the maximum allowable bias, (\delta).

- This preference structure is formalized into a rule for calculating the penalty constant (\xi). An example rule is (\xi = \frac{w}{|\hat{\mu}(x0) - T|}), where (w) is a weight reflecting the DM's preference and (x0) is a starting design point [11].

Robust Parameter Estimation (Optional but Recommended):

- To protect against outliers in experimental data, use robust estimators (e.g., MM-estimators) instead of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) to fit the models for (\hat{\mu}(x)) and (\hat{\sigma}(x)) [11].

Optimization Loop:

- Construct the penalized objective function: ( F(x) = \hat{\sigma}(x) + \xi \cdot |\hat{\mu}(x) - T| ).

- Use a suitable unconstrained optimization algorithm to minimize (F(x)).

- Validate the solution by checking that the bias (|\hat{\mu}(x^*) - T|) is within the acceptable limit (\delta).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for selecting and troubleshooting penalty methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for experiments in penalty-based optimization.

| Item / Technique | Function / Role in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Quadratic Penalty Function | Smoothly penalizes squared constraint violation, enabling use of gradient-based solvers. | Prone to ill-conditioning; requires a sequence of increasing penalty parameters [6]. |

| L1 Penalty Function | Penalizes constraint violation linearly; forms the basis for exact penalty methods. | Non-smoothness requires specialized optimizers; choice of penalty constant is critical. |

| MM-Estimators | Robust statistical estimators used to fit model parameters from data, reducing the influence of outliers [11]. | Protects the optimization process from being skewed by anomalous data points. |

| Decision Maker (DM) Preference Elicitation | A systematic procedure to formally capture trade-off preferences (e.g., bias vs. variance) to determine parameters like ξ [11]. | Moves the penalty constant selection from an ad-hoc process to a structured, justifiable one. |

| Cross-Validation | A model validation technique used to assess how the results of a statistical analysis will generalize to an independent data set. | Useful for empirically tuning the penalty constant to avoid overfitting. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why does my penalty method converge very slowly, or not at all, to a feasible solution?

- Answer: Slow convergence to a feasible solution is often due to the ill-conditioning of the unconstrained problem as the penalty parameter

pbecomes very large [6]. Aspincreases, the algorithm struggles to make progress because the Hessian of the penalized objective function becomes ill-conditioned, leading to numerical errors and slow convergence [6]. To troubleshoot:- Verify Constraint Violation Calculation: Ensure the measure of violation

g(c_i(x))is correctly implemented. For inequality constraints, this is typicallymax(0, c_i(x))^2[6]. - Adjust Penalty Increase Rate: Avoid increasing the penalty parameter

ptoo aggressively. Use a gradual update scheme (e.g.,p_{k+1} = β * p_kwhereβis a small constant like 2 or 5) to prevent immediate ill-conditioning. - Consider Algorithm Switch: For high-accuracy solutions, consider switching to an Augmented Lagrangian Method, which avoids the need to make

pgo to infinity and is less prone to ill-conditioning [6].

- Verify Constraint Violation Calculation: Ensure the measure of violation

FAQ 2: Under what theoretical conditions can I guarantee convergence for a penalty method?

- Answer: Convergence guarantees rely on specific theoretical conditions [6]:

- For global optimizers: If the objective function

fhas bounded level sets and the original constrained problem is feasible, then as the penalty coefficientpincreases, the solutions of the penalized unconstrained problems will converge to the global solution of the original problem [6]. This is particularly helpful when the penalized objective functionf_pis convex. - For local optimizers: If a local optimizer

x*of the original problem is non-degenerate, there exists a neighborhood around it and a sufficiently largep_0such that for allp > p_0, the penalized objective will have a single critical point in that neighborhood that approachesx*[6]. A "non-degenerate" point means the gradients of the active constraints are linearly independent and second-order sufficient optimality conditions are satisfied.

- For global optimizers: If the objective function

FAQ 3: What is the expected convergence rate for a modern penalty method on nonconvex problems?

- Answer: For complex nonconvex problems with nonlinear constraints, the convergence rate can be characterized by the number of iterations required to find an ε-approximate first-order stationary point. Recent research on linearized

ℓ_qpenalty methods has established a convergence rate ofO(1/ε^{2+ (q-1)/q})outer iterations to reach an ε-first-order solution, whereqis a parameter in (1, 2] that defines the penalty norm [12]. This provides a theoretical upper bound on the algorithm's complexity.

FAQ 4: How do I verify that the solution found by a penalty method satisfies optimality conditions?

- Answer: To verify optimality, you must check the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions at the proposed solution. The solution from the penalty method approximates the true KKT point. Your verification should include:

- Primal Feasibility: Check that

c_i(x) ≤ 0for all constraintsi ∈ Iwithin a small tolerance. - Dual Feasibility: Verify that the Lagrange multipliers (λ_i) for the constraints are non-negative. These are often estimated by

λ_i ≈ 2 * p * max(0, c_i(x))for a quadratic penalty. - Stationarity: Check that the gradient of the Lagrangian,

∇f(x) + Σ λ_i ∇c_i(x), is approximately zero. - Complementary Slackness: Verify that

λ_i * c_i(x) ≈ 0for alli.

- Primal Feasibility: Check that

Convergence Analysis Data

Table 1: Comparison of Penalty Method Convergence Properties

| Method / Aspect | Theoretical Convergence Guarantee | Theoretical Convergence Rate | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Quadratic Penalty | To global optimum [6] | Not specified in results | Bounded level sets, feasible original problem, convex penalized objective [6] |

| Linearized ℓ_q Penalty [12] | To an ε-first-order solution [12] | O(1/ε^{2+ (q-1)/q}) outer iterations [12] |

Locally smooth objective and constraints, nonlinear equality constraints [12] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Convergence Issues

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow convergence to feasibility | Ill-conditioning from large penalty parameter p [6] |

Use a more gradual schedule for increasing p; switch to Augmented Lagrangian method [6] |

| Convergence to an infeasible point | Penalty parameter p is too small [6] |

Increase p and restart optimization; check constraint violation implementation [6] |

| Numerical errors (overflow, NaN) | Extremely large values in the penalized objective or its gradient due to high p [6] |

Use a safeguarded optimization algorithm; re-scale the problem; employ a more numerically stable penalty function |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing and Testing a Basic Quadratic Penalty Method

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for solving a constrained optimization problem using a quadratic penalty method.

- Problem Formulation: Begin with a constrained problem:

min_x f(x)subject toc_i(x) ≤ 0. - Penalized Objective Construction: Formulate the unconstrained penalized objective:

min_x f_p(x) = f(x) + p * Σ_i ( max(0, c_i(x)) )^2. - Optimization Loop:

a. Initialize: Choose an initial guess

x_0, an initial penalty parameterp_0 > 0, and a scaling factorβ > 1. b. Solve Unconstrained Problem: For the currentp_k, use an unconstrained optimization algorithm (e.g., BFGS, Newton's method) to findx*(p_k)that minimizesf_p(x). c. Check Convergence: If the constraint violationmax_i |max(0, c_i(x))|is below a predefined tolerance, stop. The solution is found. d. Increase Penalty: Setp_{k+1} = β * p_k. e. Update Initial Guess: Usex*(p_k)as the initial guess for the next iteration withp_{k+1}. f. Iterate: Repeat steps (b) to (e) until convergence.

Protocol 2: Numerical Verification of Convergence Guarantees

This protocol outlines how to empirically test the theoretical convergence of a penalty method, aligning with frameworks used in theoretical analysis [13].

- Synthetic Problem Setup: Generate a set of test problems with known optimal solutions

x*and known optimal valuesf(x*). This allows for calculating the exact error. - Metric Definition: Define the metrics to track:

- Distance to Optimum:

||x_k - x*|| - Objective Error:

|f(x_k) - f(x*)| - Constraint Violation:

max_i |max(0, c_i(x_k))|

- Distance to Optimum:

- Algorithm Execution: Run the penalty method from Protocol 1 on the test problems, recording the defined metrics at each outer iteration

k. - Rate Calculation: Plot the metrics (e.g., Constraint Violation) against the iteration count

kon a log-log scale. The slope of the line in the limiting regime gives an empirical estimate of the convergence rate, which can be compared to theoretical bounds likeO(1/ε^{2+ (q-1)/q})[12].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Penalty Method Experiments

| Item / Concept | Function in the "Experiment" |

|---|---|

| Penalty Parameter (p) | Controls the weight of the constraint violation penalty. A sequence of increasing p values drives the solution towards feasibility [6]. |

| Penalty Function (g(c_i(x))) | A measure of constraint violation, typically max(0, c_i(x))^2 for inequalities. It transforms the constrained problem into an unconstrained one [6]. |

| Unconstrained Solver | The algorithm (e.g., BFGS, Gradient Descent) used to minimize the penalized objective f_p(x) for a fixed p [6]. |

| ℓ_q Norm (for q ∈ (1,2]) | Used in modern penalty methods to define the penalty term. The parameter q offers a trade-off, influencing the sparsity and the theoretical convergence rate [12]. |

| Quadratic Regularization | A term added to the subproblem in linearized methods to ensure boundedness and improve numerical stability, often controlled by a dynamic rule [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My penalized objective function is becoming ill-conditioned as I increase the penalty parameter, leading to slow convergence or numerical errors. What can I do? This is a common issue because large penalty parameters create very steep "walls" around the feasible region, making the Hessian of the objective function ill-conditioned [6]. To mitigate this:

- Use a Gradual Approach: Instead of starting with a very large

p, solve a sequence of unconstrained problems where you gradually increasepfrom a small value. This allows the optimization algorithm to use the solution from the previouspas a warm start for the next, more difficult problem. - Consider Alternative Methods: For high-accuracy solutions, Augmented Lagrangian Methods are often preferred as they can achieve convergence without needing to drive the penalty coefficient to infinity, thus avoiding much of the ill-conditioning [6].

Q2: How do I know if my penalty parameter is large enough to enforce the constraints effectively?

A sufficiently large penalty parameter will result in a solution that satisfies the constraints within a desired tolerance. Monitor the constraint violation c_i(x) during your optimization. If the final solution still significantly violates constraints, you need to increase p. Theoretically, the solution of the penalized problem converges to the solution of the original constrained problem as p approaches infinity [6]. In practice, you should increase p until the constraint violations fall below your pre-defined threshold.

Q3: Are there modern penalty methods that perform better for complex, non-convex problems like those in machine learning?

Yes, recent research has developed more sophisticated penalty methods. For example, the smoothing L1-exact penalty method has been proposed for challenging problems on Riemannian manifolds. This method combines the exactness of the L1-penalty (which can yield exact solutions for a finite p) with a smoothing technique to make the problem easier to solve [5]. Such advances are particularly relevant for enforcing fairness, safety, and other requirements in machine learning models [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow Convergence of the Unconstrained Solver

- Symptoms: The optimization algorithm takes many iterations to converge when minimizing

f_p(x), especially for larger values ofp. - Potential Causes:

- Ill-conditioned Problem: As

pgrows, the condition number of the Hessian off_p(x)worsens, slowing down gradient-based methods [6]. - Poor Starting Point: Starting with a very large

pfrom the beginning can trap the solver in a region of poor performance.

- Ill-conditioned Problem: As

- Solutions:

- Implement a Continuation Strategy: As outlined in FAQ 1, increase

pgradually. - Switch to a Robust Solver: Use unconstrained optimization methods that are designed to handle ill-conditioned problems effectively.

- Explore Exact Penalty Formulations: Methods like the

L1-exact penalty can sometimes avoid the need forpto go to infinity, thus mitigating the ill-conditioning issue [5].

- Implement a Continuation Strategy: As outlined in FAQ 1, increase

Problem: Infeasible Final Solution

- Symptoms: The optimization run completes, but the solution

x*does not satisfy the constraintsc_i(x*) ≤ 0to the required precision. - Potential Causes:

- Insufficient Penalty Parameter: The value of

pis not large enough to strongly penalize constraint violations. - Conflict Between Objective and Constraints: The objective function

f(x)may pull the solution strongly towards a region that is infeasible.

- Insufficient Penalty Parameter: The value of

- Solutions:

- Increase

pSystematically: Re-run the optimization with a larger penalty parameter. You may need to do this several times. - Verify Problem Formulation: Double-check that your constraints are realistic and feasible. There may be a fundamental conflict in your problem setup.

- Increase

Experimental Protocol for Penalty Method Tuning

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for empirically determining a suitable penalty parameter sequence.

1. Objective and Constraint Definition

- Define your objective function

f(x)and constraintsc_i(x) ≤ 0. - Formulate the penalized objective:

f_p(x) = f(x) + p * Σ_i g(c_i(x)), where a common choice forgis the quadratic penalty function:g(c_i(x)) = [max(0, c_i(x))]^2[6].

2. Parameter Selection Experiment

- Setup: Choose a geometrically increasing sequence of penalty parameters (e.g.,

p = 1, 10, 100, 1000, ...). - Procedure: For each value of

pin the sequence:- Minimize: Use an unconstrained optimization algorithm to find

x*(p)that minimizesf_p(x). - Warm Start: Use the solution

x*(p_prev)from the previous, smallerpas the initial guess for the next, largerp. - Record: For each run, record the final objective

f(x*(p)), the maximum constraint violationmax_i c_i(x*(p)), and the number of iterations required for convergence.

- Minimize: Use an unconstrained optimization algorithm to find

3. Analysis and Interpretation

- Create a summary table of the quantitative results from your experiment:

Penalty Parameter (p) |

Final Objective f(x*) |

Max Constraint Violation | Iterations to Convergence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| 10 | |||

| 100 | |||

| 1000 |

- Interpretation: A well-chosen sequence will show the constraint violation decreasing to an acceptable level while the objective value

f(x*)stabilizes. A sharp increase in iterations indicates the problem is becoming ill-conditioned.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Penalty Method Research | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic Penalty Function | A differentiable penalty term, [max(0, c_i(x))]^2, suitable for use with gradient-based optimizers. It penalizes violations more severely as they increase [6]. |

||

| L1-Exact Penalty Function | A non-differentiable but "exact" penalty function, `Σ_i | c_i(x) | , meaning it can recover the exact solution of the constrained problem for a finite value ofpwithout needingp→∞` [5]. |

| Smoothing Functions | Used to create differentiable approximations of non-differentiable functions (like the L1-penalty), enabling the use of standard gradient-based solvers [5]. | ||

| Extended Mangasarian-Fromovitz Constraint Qualification (EMFCQ) | A theoretical tool used to prove the boundedness of Lagrange multipliers and the global convergence of penalty methods to feasible and optimal solutions [5]. |

Penalty Method Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: The iterative process of the penalty method, showing how the penalty parameter is updated until constraints are satisfied.

Penalty Parameter Selection Strategy

Diagram 2: The trade-off in selecting the penalty parameter and the recommended strategy to balance it.

Implementing Penalty Methods: Techniques and Drug Discovery Case Studies

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the fundamental principle behind Sequential Unconstrained Minimization Techniques (SUMT)?

Sequential Unconstrained Minimization Techniques (SUMT) are a class of algorithms for solving constrained optimization problems by converting them into a sequence of unconstrained problems [6]. The core principle involves adding a penalty term to the original objective function; this term penalizes constraint violations [3] [6]. A parameter controls the severity of the penalty, which is progressively increased across the sequence of problems, forcing the solution towards feasibility in the original constrained problem [6].

How do penalty methods relate to SUMT and what are their primary components?

Penalty methods are the foundation of SUMT [6]. The modified, unconstrained objective function takes the form:

fp(x) := f(x) + p * Σ g(ci(x)) [6].

f(x): The original objective function to be minimized [6].- Penalty Function (

g(ci(x))): A function that measures the violation of the constraints. A common choice for inequality constraints is the quadratic penalty:g(ci(x)) = max(0, ci(x))^2[6]. - Penalty Parameter (

p): A positive coefficient that is sequentially increased. A largerpimposes a heavier cost for constraint violations [3] [6].

What are the main theoretical guarantees for the convergence of penalty methods?

Theoretical results ensure that under certain conditions, the solutions to the penalized unconstrained problems converge to the solution of the original constrained problem [6].

- For bounded objective functions and a feasible original problem, the set of global optimizers of the penalized problem will eventually reside within an arbitrarily small neighborhood of the global optimizers of the original problem as

pincreases [6]. - For a non-degenerate local optimizer of the original problem, there exists a neighborhood and a sufficiently large

p0such that for allp > p0, the penalized objective has exactly one critical point in that neighborhood, which converges to the original local optimizer [6].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Algorithm Configuration and Parameter Tuning

FAQ: How do I select an appropriate initial penalty parameter p and a strategy for increasing it?

Choosing the initial penalty parameter is a common challenge. If p is too small, the algorithm may venture too far into infeasible regions. If it is too large, the unconstrained problem becomes ill-conditioned early on, leading to slow convergence or numerical errors [3] [6].

- Problem: Poor convergence due to incorrect initial penalty parameter.

- Solution: Start with a moderate

p0(e.g., 1.0 or 10.0) and use a multiplicative update rule (e.g.,p_{k+1} = β * p_k, withβin [2, 10]) [6]. Monitor the constraint violation; if it remains high, increaseβ. - Solution: Implement a strategy that only increases

pif the reduction in constraint violation from the previous iteration is below a certain threshold.

FAQ: My algorithm is converging slowly. What might be the cause?

Slow convergence in SUMT can stem from several factors, primarily related to the penalty function and the solving of the unconstrained subproblems.

- Problem: Ill-conditioning of the unconstrained subproblem due to a very large penalty parameter

p[6]. - Solution: Instead of a simple penalty method, consider an Augmented Lagrangian Method, which incorporates a Lagrange multiplier estimate to allow for high-accuracy solutions without driving

pto infinity [6]. - Solution: Use a robust, second-order unconstrained optimization method (e.g., Newton's method) that can better handle ill-conditioned problems [15].

Numerical and Implementation Issues

FAQ: The solver for my unconstrained subproblem is failing to find a minimum. What should I check?

The success of SUMT hinges on reliably solving each unconstrained subproblem.

- Problem: The unconstrained solver fails to converge.

- Solution: Verify the smoothness of your penalized objective function. Non-differentiable penalty functions can cause problems for gradient-based solvers [16].

- Solution: Use the solution from the previous (lower

p) unconstrained problem as the initial guess for the next one. This "warm-start" strategy often improves convergence [17].

FAQ: How can I handle a mix of equality and inequality constraints effectively?

The type of constraints influences the choice of the penalty function.

- Problem: Difficulty in satisfying equality constraints.

- Solution: It is often beneficial to eliminate equality constraints by solving for the dependent variables (

xD) in terms of the independent ones (xI). This reduces the problem to one involving only inequality constraints, which are then handled by the penalty function [3]. The optimization is performed only over the independent variablesxI.

Problem Formulation and Modeling

FAQ: How does the choice of penalty function impact the performance and solution quality?

Different penalty functions lead to different numerical behavior.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Penalty Functions

| Penalty Function | Formulation (for ci(x) ≤ 0) | Key Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic | p * Σ (max(0, ci(x))^2 [6] |

Smooth (differentiable), but may allow some infeasibility for finite p. |

||

| Deadzone-Linear [6] | Not specified in detail | Less sensitive to small violations, can be non-differentiable. | ||

| mBIC (Complex) | `3 | T | log T + Σ log((t{k+1} - tk)/T)` [3] | Example of a complex, non-linear penalty; requires specialized optimization. |

FAQ: When should I consider using SUMT over other constrained optimization algorithms?

SUMT is a versatile approach, but alternatives exist.

- Problem: Deciding whether SUMT is suitable.

- Solution: SUMT is attractive when you have efficient and robust unconstrained optimization solvers at your disposal. It is widely used in computational mechanics and engineering [6].

- Solution: For problems requiring high accuracy without extreme ill-conditioning, consider Barrier Methods (for strictly feasible interiors) or Augmented Lagrangian Methods (generally more robust) [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Basic SUMT with Quadratic Penalty for Drug Molecule Property Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps to optimize a molecular property (e.g., binding affinity) while constraining pharmacokinetic properties (e.g., solubility, toxicity) within a desired range, using a quadratic penalty method.

1. Problem Formulation:

- Objective Function:

f(x) = -pKi(negative predicted binding affinity to be minimized). - Inequality Constraints:

c1(x) = logS_low - logS(x) ≤ 0,c2(x) = logS(x) - logS_high ≤ 0(solubility within a range);c3(x) = Toxicity(x) - Toxicity_threshold ≤ 0.

2. Algorithm Setup:

- Penalty Function: Quadratic.

P(x) = p * [ (max(0, c1(x)))^2 + (max(0, c2(x)))^2 + (max(0, c3(x)))^2 ]. - Penalty Parameter Sequence: Choose

p0 = 1.0, update rulep_{k+1} = 5.0 * p_k. - Convergence Tolerance:

ε = 1e-6for the norm of the gradient of the penalized objective,fp(x). - Unconstrained Solver: Select a robust algorithm like L-BFGS-B or Newton-CG [16].

3. Execution:

- Step 1: Initialize

p = p0and an initial molecular designx0. - Step 2: Minimize

fp(x) = f(x) + P(x)using the chosen unconstrained solver. - Step 3: If

||∇fp(x)|| < ε, check constraint violation. If all constraints are satisfied to a desired tolerance, terminate. Otherwise, proceed. - Step 4: Update

p = p_{k+1}. - Step 5: Set the new initial point to the solution from Step 2. Return to Step 2.

Protocol 2: SUMT with Equality Constraint Elimination for Flow Sheet Optimization

This protocol is adapted from chemical engineering applications where process flowsheets must be optimized [3]. It demonstrates the elimination of equality constraints (simulating the convergence of the flowsheet) from the optimization problem.

1. Problem Formulation and Variable Partitioning:

- Variables: Identify and partition variables into independent (

xI) and dependent (xD) sets.xIare the decision variables (e.g., reactor temperature, feed rate).xDare the variables determined by solving the process model equations (e.g., recycle stream compositions). - Objective:

min f(xI, xD)(e.g., maximize profit). - Equality Constraints:

c(xI, xD) = 0(the process model equations). - Inequality Constraints:

g(xI, xD) ≤ 0(safety, purity limits).

2. Penalty Function Setup:

- The optimization problem is re-written as:

min_{xI} ψ(xI) = f(xI, xD(xI)) + p * ||g+(xI, xD(xI))||[3], wherexD(xI)is obtained by solvingc(xI, xD) = 0for any givenxI.

3. Execution:

- Step 1: Make an initial guess for

xI. - Step 2: Inner Loop: Given

xI, solve the equality constraintsc(xI, xD) = 0to obtainxD. This is equivalent to converging the flowsheet simulation [3]. - Step 3: Outer Loop: With

xDnow a function ofxI, evaluate the penalized objectiveψ(xI)and its gradient with respect toxI. - Step 4: Use an unconstrained optimization method to update

xI. - Step 5: Repeat from Step 2 until convergence. The penalty parameter

pcan be increased sequentially for tighter satisfaction of the inequality constraintsg(x).

Framework Visualization and Workflows

SUMT High-Level Workflow

SUMT Iterative Process

Troubleshooting Decision Tree

SUMT Problem Diagnosis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for SUMT Implementation in Drug Discovery

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in the 'Experiment' |

|---|---|

| Unconstrained Optimization Solver | The core computational engine for minimizing the penalized objective function (e.g., L-BFGS, Conjugate Gradient, Newton's method) [16] [15]. |

Penalty Function (P(x)) |

The mathematical construct that incorporates constraints into the objective, quantifying violation (e.g., Quadratic, L1) [6]. |

| Penalty Parameter Update Schedule | A predefined rule (e.g., multiplicative) for increasing the penalty parameter p to enforce constraint satisfaction [6]. |

| Automatic Differentiation Tool | Software library to compute precise gradients and Hessians of the penalized objective, crucial for efficient solver performance [16]. |

| Molecular Property Predictor | In-silico model (e.g., QSAR, AI-based) that predicts properties like toxicity or solubility for a candidate molecule, acting as the constraint function c(x) [18]. |

| Molecular Generator / Sampler | A method to propose new candidate molecules (x); can be a simple sampler or a generative AI model for de novo design [18]. |

Exact Penalty Methods for Stress-Constrained Topology and Reliability Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the common causes of numerical instability when using exact penalty methods, and how can they be mitigated?

Numerical instability in exact penalty methods often arises from the use of discontinuous operations like max and abs functions, which are inherent in traditional L1 exact penalty formulations. These discontinuities make the optimization procedure numerically unstable and are not suitable for gradient-based approaches [19]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Using a smooth, differentiable exact penalty function to avoid discontinuous operations [19].

- Implementing a smooth scheme for complementary conditions [19].

- Applying an adaptive adjusting scheme for the stress penalty factor to improve control over local stress levels and enhance convergence [20].

Q2: How do I select an appropriate penalty parameter/gain for stress-constrained topology optimization? Selecting a suitable penalty gain is crucial for the exact penalty method's performance. The process involves:

- A suitably selected gain is constructed using an active function inspired by topology optimization principles [19].

- For stress-constrained problems, an adaptive volume constraint and stress penalty method can be employed, where the penalty factor is adjusted to control the local stress level [20].

- The penalty term can be introduced to change the right-hand side (RHS) value of deterministic constraints without linearizing or transforming the limit-state function formulations [21].

Q3: My optimization converges to an infeasible design that violates stress constraints. What might be wrong? Convergence to an infeasible design typically indicates issues with constraint handling:

- The initial penalty parameter might be too small, providing insufficient constraint enforcement [19].

- The method may require a more robust active set detection. Consider using a differentiating active function to control the presence or absence of any constraint function [19].

- For stress-constrained problems, ensure proper integration of stress penalty with your optimization framework, potentially using the parametric level set method with compactly supported radial basis functions [20].

Q4: What is the relationship between the optimality conditions of the proposed penalty function and the traditional KKT conditions? The first-order necessary optimality conditions for the unconstrained optimization formulation using the exact penalty function maintain a direct relationship with the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions of the original constrained problem [19]. When the gradient of the proposed penalty function F(x) is set to zero, it yields conditions that relate to the traditional KKT conditions, ensuring theoretical consistency while avoiding the need for dual and slack variables [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Convergence in Reliability-Based Design Optimization (RBDO)

Symptoms: Slow convergence, oscillating design variables, or failure to reach feasible reliable design.

Solution Protocol:

- Implement Decoupled Approach: Transform the nested RBDO problem into sequential deterministic optimization and reliability analysis loops [21].

- Apply Penalty to Constraint RHS: Introduce penalty terms to change the right-hand side value of deterministic constraints rather than linearizing limit-state functions [21].

- Iterative Improvement: After determining mean values through initial deterministic optimization, perform reliability analysis and restructure the optimization problem with penalties to improve solutions iteratively [21].

Table: Key Parameters for RBDO Convergence

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Effect on Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| Penalty Type | RHS modification | Avoids approximation error from limit-state linearization [21] |

| Initial Multipliers | Prior knowledge exploitation | Improves starting point for iterative process [19] |

| Convergence Tolerance | Adaptive scheme | Balances accuracy and computational cost [21] |

Problem: Computational Bottlenecks in Large-Scale Stress-Constrained Problems

Symptoms: Prohibitive computation time, memory issues, or inability to handle many constraints.

Solution Protocol:

- Eliminate Dual Variables: Use a differentiating exact penalty scheme that avoids unnecessary dual and slack variables for handling constraints [19].

- Apply Adaptive Schemes: Implement adaptive volume constraint and stress penalty methods to transform complex problems into simpler sub-problems [20].

- Utilize Efficient Solvers: For stress-penalty based compliance minimization, adopt the parametric level set method with compactly supported radial basis functions [20].

Table: Computational Efficiency Comparison of Methods

| Method | Computational Features | Constraint Handling Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Lagrange Multiplier | High memory usage for dual variables [19] | Dual variables for each constraint [19] |

| Proposed Exact Penalty | Avoids dual/slack variables [19] | Differentiating active function [19] |

| Adaptive Volume-Stress Penalty | Transforms to simpler sub-problems [20] | Stress penalty with adaptive factor [20] |

Problem: Handling Inactive/Active Constraints in Topology Optimization

Symptoms: Inability to properly identify which constraints are active, leading to suboptimal designs.

Solution Protocol:

- Implement Active Function: Design a differentiating active function inspired by topology optimization principles to indicate the existence of any constraint function [19].

- Develop Loss Functions: Create loss functions that measure constraint violation using a mapping relationship to measure constraint feasibility [19].

- Nested Formulation: For inequality constraints, use a nested form loss function by replacing the active function with the constraint function [19].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Smooth Exact Penalty Function Implementation

Purpose: To solve stress-constrained topology optimization without dual and slack variables [19].

Materials:

- Nonlinear constrained optimization problem with design variables x ∈ Râ¿

- Objective function f(x) and constraint functions hᵢ(x) = 0, gⱼ(x) ≤ 0

- Active function χ(x) based on topology optimization penalty principle

Procedure:

- Design Active Function: Create active function χ(x) = H[ψ(x)]·[ψ(x)]^κ where H is Heaviside function, ψ is constraint function [19].

- Construct Loss Functions: Develop loss functions for equality and inequality constraints using the active function framework [19].

- Formulate Penalty Function: Build the nested form penalty function incorporating constraint functions into loss functions [19].

- Solve Unconstrained Problem: Optimize the resulting unconstrained formulation using gradient-based methods [19].

Protocol 2: Adaptive Volume Constraint with Stress Penalty

Purpose: To obtain lightweight designs meeting stress constraints while optimizing compliance [20].

Materials:

- Structural domain with stress constraints

- Parametric level set method with compactly supported radial basis functions

- Adaptive penalty factor adjustment scheme

Procedure:

- Problem Transformation: Convert stress-constrained volume and compliance minimization into stress-penalty based compliance minimization and volume-decision sub-problems [20].

- Stress Penalty Application: Apply stress penalty to control local stress levels using parametric level set method [20].

- Adaptive Penalty Adjustment: Implement adaptive adjusting scheme for stress penalty factor to improve stress control [20].

- Volume Decision: Solve volume-decision problem using combination scheme of interval search and local search [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Exact Penalty Methods

| Tool/Component | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiating Active Function | Indicates existence of constraint functions [19] | Based on topology optimization penalty principle |

| Nested Loss Functions | Measures constraint violation [19] | Replaces constraint functions in penalty formulation |

| Adaptive Penalty Factor | Controls local stress levels [20] | Requires careful adjustment scheme |

| Parametric Level Set Method | Solves stress-penalty compliance minimization [20] | Uses compactly supported radial basis functions |

| Heaviside Function Approximation | Enables smooth transitions in active functions [19] | Critical for numerical stability |

Workflow Visualization

Exact Penalty Method Workflow

Constraint Handling Transformation

Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) in Peptide-Protein Docking

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary advantage of using a QUBO formulation for peptide-protein docking? The primary advantage is the ability to leverage quantum-amenable optimization solvers, such as quantum annealers or variational algorithms, to find optimal docking conformations. The QUBO formulation translates the complex biological problem of finding a peptide's 3D structure on a target protein into a minimization problem of a quadratic function of binary variables, which is a standard input for these solvers [22] [23].

How are physical constraints, like preventing atomic clashes, incorporated into the QUBO model? Physical constraints are incorporated by adding penalty terms to the QUBO Hamiltonian. For example, a steric clash constraint is enforced by adding a high-energy penalty to the objective function whenever two peptide particles or a peptide particle and a blocked protein site are placed on the same lattice vertex. The use of appropriate penalty weights is critical to ensure that these constraints are satisfied in the optimal solution [22] [24].

My QUBO model fails to find feasible solutions that satisfy all cyclization constraints. What could be wrong?

This is often a problem of penalty function tuning. The Hamiltonian term for cyclization (H_cycle) must be assigned a sufficiently high penalty weight to make any solution violating the cyclization bond energetically unfavorable compared to feasible solutions. If the weight is too low, the solver may prioritize lower interaction energy over satisfying the constraint. A systematic hyperparameter search, for instance using Bayesian optimization, is recommended to find the correct balance [23] [25].

Why does my QUBO model scale poorly with increasing peptide residues? The QUBO formulation for lattice-based docking is an NP-complete problem. The number of binary variables required grows rapidly with the number of peptide residues and the size of the protein's active site, quickly exceeding the capacity of current classical and quantum hardware. Research indicates that QUBO models using simulated annealing can find feasible conformations for peptides with up to 6 residues but struggle with larger instances [22] [23] [24].

What is a viable classical alternative if my QUBO model does not scale? Constraint Programming (CP) is a powerful classical alternative. Unlike QUBO, which combines objectives and constraints into a single penalty function, CP uses a declarative approach to explicitly define variables, their domains, and constraints. This allows CP solvers to efficiently prune the search space. Studies have shown that CP models can find optimal solutions for problems with up to 11-13 peptide residues, where QUBO models fail [22] [23] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Solver Returns High-Energy or Non-Native Conformations

This occurs when the predicted peptide structure has a high (unfavorable) Miyazawa-Jernigan (MJ) interaction energy or a high Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) from the known native structure.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

Incorrect penalty weight in H_protein for steric clashes. |

Check if any peptide residues are placed on lattice vertices within the blocking radius (e.g., 3.8Ã…) of the protein. | Increase the penalty weight for the steric hindrance term in H_protein to completely forbid such placements [23] [24]. |

| Poorly tuned QUBO hyperparameters. | Perform a sensitivity analysis on the weights of the different Hamiltonian terms (H_comb, H_back, H_cycle, H_protein). |

Use automated hyperparameter optimization (e.g., Bayesian optimization via Amazon SageMaker) to find parameter sets that yield low-energy, feasible solutions [23]. |

| Discretization error from the lattice. | Compare the continuous atomic coordinates from the PDB with the discrete lattice vertices. A fundamental error is introduced. | Consider using a finer-grained lattice or a post-processing step with continuous energy minimization to refine the lattice-based solution [26]. |

Problem: Model Fails to Scale Beyond Small Peptides

This refers to the inability to find a solution for peptides with more than approximately 6 residues within a reasonable time or memory footprint.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial explosion of the problem space. | Monitor the rapid growth in the number of binary variables as peptide length increases. | For larger peptides, switch to a Constraint Programming (CP) approach, which has been demonstrated to handle larger instances effectively [22] [25]. |

| Inefficient encoding strategy. | Analyze the number of variables used by your encoding (e.g., spatial vs. turn encoding). | Adopt a "resource-efficient" turn encoding, which has been shown to require fewer variables than spatial encodings for representing peptide chains [22] [24]. |

| Limitations of the classical solver. | If using simulated annealing, observe the solution quality plateauing with increased runtime. | For QUBO models, experiment with more advanced hybrid solvers or, if available, quantum annealing hardware to explore if they offer better scaling properties [27]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Standardized Docking Pipeline

The following workflow, derived from published research, ensures a consistent and reproducible process for preparing and solving docking problems [23].

Performance Benchmarking Data

The table below summarizes the performance of QUBO (solved with simulated annealing) versus Constraint Programming (CP) on real peptide-protein complexes from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). This data provides a benchmark for expected performance [23].

| PDB ID | Peptide Residues | Protein Residues | Method | MJ Potential | RMSD (Ã…) | Feasible Found? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3WNE | 6 | 26 | QUBO | -28.53 | 8.88 | Yes |

| CP | -42.64 | 8.48 | Yes | |||

| 5LSO | 6 | 34 | QUBO | -17.93 | 7.68 | Yes |

| CP | -23.26 | 10.29 | Yes | |||

| 3AV9 | 8 | 28 | QUBO | -- | -- | No |

| CP | -40.44 | 8.98 | Yes | |||

| 2F58 | 11 | 49 | QUBO | -- | -- | No |

| CP | Solved | Solved | Yes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table details the essential components and their functions for constructing and solving QUBO models for peptide-protein docking.

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedral Lattice | Provides a discrete 3D space to model peptide conformation, reducing the problem from continuous to combinatorial search [22] [24]. | A set of vertices (\mathcal{T}) in 3D space with tetrahedral coordination. |

| Coarse-Grained (CG) Representation | Simplifies the molecular system, reducing computational complexity. Each amino acid is represented by 1-2 particles (main chain and side chain) [23] [24]. | Two-particle model for standard residues; one-particle for Glycine. |

| Miyazawa-Jernigan (MJ) Potential | A scoring function that estimates the interaction energy between amino acid residues, used as the objective to minimize [22] [26]. | Lookup table of fixed interaction potentials for unique pairs of amino acid types. |

QUBO Hamiltonian (H) |

The core mathematical model that integrates all problem objectives and constraints into a single quadratic function of binary variables [22] [24]. | (H = H\textrm{comb} + H\textrm{back} + H\textrm{cycle} + H\textrm{protein}) |

| Steric Clash Radius | Defines the minimal allowed distance between atoms, preventing physically impossible overlapping conformations [23]. | Typically set to 3.8Ã… for determining which lattice vertices are blocked by the protein. |

| Protein Active Site | A focused region of the target protein where docking is likely to occur, drastically reducing the search space and computational cost [23] [24]. | Residues within a specified distance (e.g., 5Ã…) from the peptide in the native complex. |

QUBO Framework Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical structure of the full QUBO Hamiltonian, showing how different constraints and objectives are combined using penalty functions [22] [23] [24].

Constrained Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization (CMOMO) for Drug-like Candidates

Constrained Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization (CMOMO) represents an advanced artificial intelligence framework specifically designed to address the complex challenges of molecular discovery in drug development. This approach simultaneously optimizes multiple molecular properties while adhering to stringent drug-like constraints, which is a critical requirement in practical pharmaceutical applications [28]. Traditional molecular optimization methods often neglect essential constraints, limiting their ability to produce viable drug candidates. CMOMO addresses this gap by implementing a sophisticated penalty-based constraint handling mechanism within a multi-objective optimization framework, enabling researchers to identify molecules that balance optimal property profiles with strict adherence to drug-like criteria [29].

The foundation of CMOMO rests on formulating molecular optimization as a constrained multi-objective problem, where each property to be enhanced is treated as an optimization objective, and stringent drug-like criteria are implemented as constraints. This formulation differs significantly from both single-objective optimization and unconstrained multi-objective optimization, as it must navigate the challenges of narrow, disconnected, and irregular feasible molecular spaces caused by constraint imposition [28]. The framework employs a dynamic cooperative optimization strategy that evolves molecules in continuous latent space while evaluating properties in discrete chemical space, creating an effective mechanism for discovering high-quality candidate molecules.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization in Molecular Context

In CMOMO, constrained multi-property molecular optimization problems are mathematically expressed as:

min F(x) = (fâ‚(x), fâ‚‚(x), …, fₘ(x)) subject to gáµ¢(x) ≤ 0,â€âˆ€i ∈ {1, …, p} hâ±¼(x) = 0,â€âˆ€j ∈ {1, …, q} x ∈ ð’®

Where x represents a molecule within the molecular search space ð’®, F(x) is the objective vector comprising m optimization properties, and gáµ¢(x) and hâ±¼(x) are inequality and equality constraints, respectively [28].

Constraint Violation Measurement

The Constraint Violation (CV) function quantitatively measures the degree to which a molecule violates constraints:

$$CV(x) = \sum{i=1}^{p} \max(0, gi(x)) + \sum{j=1}^{q} |hj(x)|$$

A molecule is considered feasible when CV(x) = 0, and infeasible otherwise [28]. This metric enables the algorithm to prioritize molecules that better satisfy constraints during the optimization process.

Multi-Objective Optimization Fundamentals

Multi-objective optimization differs fundamentally from single-objective approaches by seeking a set of optimal solutions representing trade-offs among competing objectives, rather than a single optimal solution. In molecular design, this approach reveals the complex relationships between various molecular properties, providing researchers with multiple candidate options along the Pareto front [30] [31]. This is particularly valuable in drug discovery, where researchers must balance conflicting requirements such as potency, solubility, and metabolic stability.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CMOMO Workflow Implementation

The CMOMO framework implements a structured two-stage optimization process:

Population Initialization:

- Given a lead molecule represented as a SMILES string, CMOMO first constructs a Bank library containing high-property molecules similar to the lead molecule from public databases

- A pre-trained encoder embeds the lead molecule and Bank library molecules into a continuous latent space

- Linear crossover between the latent vector of the lead molecule and those in the Bank library generates a high-quality initial molecular population [28] [29]

Dynamic Cooperative Optimization:

- Unconstrained Scenario: CMOMO employs a Vector Fragmentation-based Evolutionary Reproduction (VFER) strategy on the implicit molecular population to efficiently generate offspring in continuous latent space

- Molecules are decoded from latent space to discrete chemical space using a pre-trained decoder for property evaluation