TIR-NBS-LRR Domain Architectures: Evolutionary Patterns, Computational Identification, and Functional Validation in Plant Immunity

This comprehensive review explores the diversity, evolution, and function of TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) domain architectures in plant disease resistance.

TIR-NBS-LRR Domain Architectures: Evolutionary Patterns, Computational Identification, and Functional Validation in Plant Immunity

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the diversity, evolution, and function of TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) domain architectures in plant disease resistance. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, we examine the evolutionary distribution of TNL genes across plant lineages, their absence in monocots, and structural variations. The article details computational methods for genome-wide identification, troubleshooting for accurate annotation, and validation through expression profiling and functional studies. Synthesizing recent genomic findings, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with methodological frameworks and future directions for leveraging TNL genes in crop improvement and disease resistance breeding.

Evolutionary Origins and Structural Diversity of TIR-NBS-LRR Proteins

Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor Nucleotide-Binding Site Leucine-Rich Repeat (TNL) proteins represent a crucial class of intracellular immune receptors in plants, serving as specialized surveillance machinery that detects pathogen effector molecules and initiates robust defense signaling cascades. These proteins belong to the broader nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) family, which constitutes the largest and most functionally diverse group of plant disease resistance (R) genes [1]. TNL proteins are characterized by a distinctive tripartite domain architecture that facilitates their role in pathogen perception and immune activation. Understanding the precise molecular organization of these domains and their conserved motifs is fundamental to deciphering the mechanisms of plant innate immunity and engineering disease-resistant crops. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of TNL domain architectures, detailing their structural components, conserved motifs, and the experimental methodologies employed in their characterization, thereby offering an essential resource for researchers investigating plant-pathogen interactions.

TNL Domain Architecture: A Tripartite Structure

The canonical TNL protein structure comprises three fundamental domains that work in concert to fulfill its immune receptor function. The N-terminal Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) domain is responsible for initiating downstream signaling, the central Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) domain acts as a molecular switch for activation, and the C-terminal Leucine-Rich Repeat (LRR) domain facilitates pathogen recognition and autoinhibition [1] [2]. This modular organization enables TNL proteins to perceive specific pathogen effectors and transduce this recognition into effective defense responses, often culminating in a hypersensitive response (HR) that limits pathogen spread at the infection site.

Table 1: Core Domains of TNL Proteins

| Domain | Position | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIR | N-terminal | Signaling initiation | Shares homology with Drosophila Toll and mammalian IL-1 receptors; forms homodimers |

| NBS (NB-ARC) | Central | Molecular switch & nucleotide binding | Binds and hydrolyzes ATP; contains conserved kinase motifs; regulates activation state |

| LRR | C-terminal | Pathogen recognition & autoinhibition | Highly variable; mediates protein-protein interactions; determines recognition specificity |

Beyond the typical TNL structure, genomic studies have identified related variants with distinct domain compositions. For instance, in Nicotiana benthamiana, researchers have characterized not only full-length TNLs but also truncated forms classified as TN-type (TIR-NBS), which lack the LRR domain [3]. These irregular-type NBS-LRR proteins are hypothesized to function as adaptors or regulators for their typical counterparts, adding complexity to the plant immune network [3].

Conserved Motifs and Signature Sequences

Within each major domain of TNL proteins, highly conserved sequence motifs mediate critical biochemical functions, particularly within the NBS domain where nucleotide binding and hydrolysis occur. These motifs serve as signatures for identifying TNL genes and distinguishing them from their CNL (CC-NBS-LRR) counterparts through bioinformatic analyses [2] [4].

Table 2: Conserved Motifs in TNL NBS Domains

| Motif Name | Consensus Sequence (TNL-specific) | Functional Role | Subfamily Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-loop/Kinase 1a | GxGKT/S | ATP/GTP binding | Common to both TNL and CNL |

| RNBS-A | FLENIRExSKKHGLEHLQKKLLSKLL | Structural stability | Diagnostic for TNL [5] |

| Kinase-2 | LLVLDDVD | ATP hydrolysis | Diagnostic (final Asp for TNL) [5] |

| RNBS-C | Not specified | Unknown function | Distinct in TNL vs. CNL [1] |

| RNBS-D | FLHIACFF | Structural role | Diagnostic for TNL [5] |

| GLPL | CxGLPLA/GLK | Protein interaction | Common to both TNL and CNL |

The kinase-2 motif deserves special attention as its final residue provides a key diagnostic feature for distinguishing TNL from CNL proteins. TNL sequences consistently contain an aspartic acid (D) at this position, forming the "LLVLDDVD" signature, whereas CNL proteins typically feature a tryptophan (W) instead, resulting in "LLVLDDVW" [5]. This subtle but consistent difference enables reliable classification of NBS-LRR proteins through sequence analysis alone.

Comparative Genomic Distribution of TNL Genes

TNL genes demonstrate remarkable variation in their representation across plant lineages, reflecting distinct evolutionary paths in different taxonomic groups. Comprehensive genomic analyses reveal that TNLs are present in bryophytes, gymnosperms, and eudicots but are conspicuously absent from monocot genomes, with the exception of basal angiosperms like Amborella trichopoda [5] [6]. This distribution pattern suggests that TNL sequences were present in early land plants but have been significantly reduced or lost in monocot and magnoliid lineages [5].

Recent genome-wide studies illustrate this variation in specific species:

- Nicotiana benthamiana: 5 TNL-type genes identified among 156 NBS-LRR homologs [3]

- Capsicum annuum (pepper): Only 4 TNL genes identified among 252 NBS-LRR resistance genes [2]

- Gossypium hirsutum (cotton): 122 TNL genes identified from 437 NBS-LRR genes [4]

- Fragaria species (wild strawberries): TNLs present but outnumbered by non-TNL types in all eight diploid species examined [6]

This uneven distribution highlights the dynamic evolution of TNL genes and suggests that different plant families have employed distinct strategies for pathogen recognition, with some lineages expanding their TNL repertoires while others have preferentially amplified CNL-type receptors.

Experimental Protocols for TNL Characterization

Genome-Wide Identification Pipeline

The standard workflow for identifying and characterizing TNL genes combines bioinformatic predictions with experimental validation:

HMMER Search: Perform HMMsearch using the NB-ARC (PF00931) domain model from Pfam database with expectation value (E-values < 1*10â»Â²â°) against the target genome [3] [7].

Domain Verification: Confirm identified sequences using SMART tool and conserved domain database (CDD) to verify presence of TIR, NBS, and LRR domains [3].

Motif Analysis: Identify conserved motifs using MEME suite with motif count set to 10 and width lengths from 6-50 amino acids [3] [2].

Subcellular Localization: Predict localization using CELLO v.2.5 and Plant-mPLoc tools [3].

Gene Structure Analysis: Determine exon-intron organization using GFF3 annotation files and visualization with TBtools [3].

Cis-Element Analysis: Identify regulatory elements in promoter regions (1500-2000 bp upstream of ATG) using PlantCARE database [3] [8].

Functional Characterization Approaches

Several experimental methods enable functional analysis of TNL proteins:

Heterologous Expression: Express TNL genes in susceptible genotypes to validate function, as demonstrated by improved resistance to Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis thaliana expressing maize NBS-LRR genes [7].

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS): Knock down TNL expression to confirm necessity for resistance, as shown in cotton where silencing reduced resistance to Verticillium dahliae [7].

Allelic Mutagenesis: Introduce mutations in conserved motifs to determine their functional significance, as evidenced by premature senescence in wheat with mutated NBS-LRR genes [9].

In vitro Assays: Perform leaf inoculation assays with pathogens like Botrytis cinerea to correlate TNL presence with resistance levels across different genotypes [6].

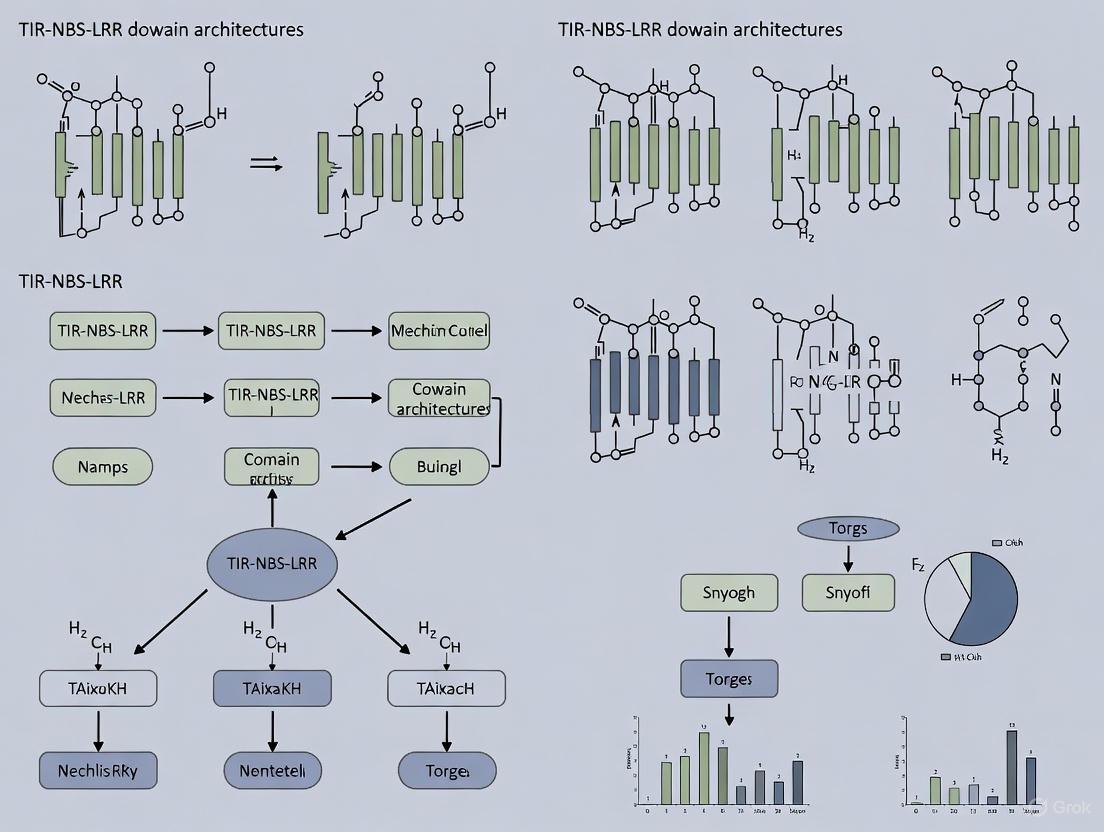

TNL Activation and Characterization Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for TNL Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Application Example | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pfam PF00931 | NB-ARC domain HMM profile | Identification of NBS-containing genes | Pfam Database [3] |

| Pfam PF01582 | TIR domain HMM profile | Verification of TIR domain presence | Pfam Database [2] |

| MEME Suite | Conserved motif discovery | Identification of P-loop, kinase-2, GLPL motifs | [3] [2] |

| PlantCARE | Cis-element prediction | Analysis of promoter regulatory elements | [3] [8] |

| CELLO v.2.5 | Subcellular localization prediction | Determining cytoplasmic/nuclear localization | [3] |

| MCScanX | Gene duplication analysis | Identifying tandem and segmental duplications | [7] [6] |

| OrthoFinder | Orthogroup analysis | Comparing NLR genes across species | [8] |

The comprehensive analysis of TNL architecture reveals a sophisticated immune receptor system whose functionality emerges from the precise arrangement and interaction of its core domains and conserved motifs. The integrated approach combining bioinformatic identification, phylogenetic analysis, motif characterization, and functional validation provides a powerful framework for deciphering TNL structure-function relationships. As genomic resources continue to expand across diverse plant species, comparative analyses of TNL genes will further illuminate their evolutionary dynamics and functional specialization. The research tools and methodologies outlined in this guide offer a foundation for systematic investigation of TNL proteins, accelerating discoveries in plant immunity and facilitating the development of novel disease control strategies in agriculture. Future research focusing on the structural basis of TNL activation and signaling will undoubtedly yield new insights into the molecular mechanisms governing plant-pathogen interactions.

The Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor-Nucleotide-Binding Site-Leucine-Rich Repeat (TIR-NBS-LRR or TNL) class of plant disease resistance (R) genes represents a crucial component of the plant immune system, enabling recognition of diverse pathogens and triggering robust defense responses [10] [1]. Despite their functional importance, these genes exhibit a strikingly uneven distribution across the plant kingdom. A well-documented pattern in plant evolutionary biology is the predominant presence of TNL genes in dicotyledonous plants (dicots) and their conspicuous absence or extreme rarity in monocotyledonous plants (monocots) [5] [11] [1]. This comparative guide objectively analyzes the experimental evidence underpinning this phylogenetic distribution, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a synthesized overview of supporting data, methodologies, and implications for plant immunity research.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of TNL Distribution

Table 1: Genomic Distribution of TNL Genes Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Classification | Total NBS-LRR Genes Identified | TNL Genes Identified | Key Study Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Dicot (Eudicot) | ~150 | 62 (of 150 NBS-LRRs) | One of two major NBS-LRR subfamilies; forms distinct clade from CNLs. | [1] |

| Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa) | Dicot (Eudicot) | Not Specified | 90 | Genes physically mapped to chromosomes; expansion due to whole-genome triplication. | [12] |

| Tung Tree (Vernicia montana) | Dicot (Eudicot) | 149 | 12 (3 TNL, 7 TN, 2 CC-TIR-NBS) | TIR domains present, confirming retention in eudicots. | [13] |

| Cassava (Manihot esculenta) | Dicot (Eudicot) | 228 | 34 | TIR-containing genes identified among NBS-LRR repertoire. | [14] |

| Wild Strawberry (Fragaria spp.) | Dicot (Eudicot) | Varies by species | Present (Proportion < Non-TNLs) | Non-TNLs constitute >50% of NLRs, but TNLs are consistently present. | [6] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Monocot (Cereal) | >600 | 0 (or nearly 0) | TIR-domain coding genes are present but have diverged from NBS-LRR genes. | [11] |

| Vernicia fordii | Dicot (Eudicot) | 90 | 0 | A rare documented case of TNL loss within a eudicot species. | [13] |

| Various Monocots (Poales, Zingiberales, etc.) | Monocot | Not Specified | 0 | PCR and database searches across five monocot orders failed to find TNL sequences. | [5] |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates a clear phylogenetic trend: TNL genes are a standard, often expanded, component of the immune repertoire in dicots, whereas they are consistently missing from the genomes of monocots, particularly cereals. An exceptional case is the susceptible tung tree (Vernicia fordii), which has lost its TNL genes, unlike its resistant relative [13]. This loss correlates with susceptibility to Fusarium wilt, suggesting a potential fitness cost or functional redundancy.

Key Experimental Methodologies for Investigating TNL Phylogeny

Research into the distribution of TNL genes relies on a combination of bioinformatic and molecular biology techniques. Below are the detailed protocols for the key methodologies cited in the comparative studies.

Genome-Wide Identification and Domain Analysis

This bioinformatic approach is the standard for comprehensively cataloging NBS-LRR genes in sequenced genomes [13] [14] [6].

- Data Retrieval: Obtain the complete proteome and genome annotation file (GFF/GTF) for the target species from public databases (e.g., Phytozome, NCBI, BRAD).

- HMMER Search: Use the HMMER software suite (e.g.,

hmmsearch) with a pre-built Hidden Markov Model (HMM) for the NB-ARC (NBS) domain (Pfam: PF00931) to scan the proteome. An E-value cutoff (e.g., < 0.01 or < 1x10â»Â²â°) is applied for initial candidate selection [14] [6]. - Domain Annotation: Subject the candidate sequences to further domain analysis using tools like PfamScan, SMART, and NCBI's CD-Search to identify associated domains (TIR: PF01582, CC, LRR: various Pfams) [14] [6].

- Coiled-Coil Prediction: Since CC domains are not always identified by Pfam, use tools like COILS or Paircoil2 with a specific probability cutoff (e.g., 0.03) to predict their presence [14] [6].

- Classification and Curation: Classify genes into subgroups (TNL, CNL, NL, etc.) based on their domain architecture. Manual curation is essential to remove false positives, such as genes with partial kinase domains.

Degenerate PCR and Sequence Analysis

This molecular method is used to survey species without a sequenced genome or to validate genomic findings [5] [15].

- Primer Design: Design degenerate primers targeting conserved motifs within the NBS domain, such as the P-loop (kinase-1a) and the GLPL or MHD motifs [5] [11].

- PCR Amplification: Perform PCR on genomic DNA using touchdown or standard cycling protocols to allow for primer degeneracy.

- Cloning and Sequencing: Clone the resulting PCR products (~500-1000 bp) into a plasmid vector, transform bacteria, and sequence multiple clones to capture diversity.

- Sequence Classification:

- Translate DNA sequences into amino acid sequences.

- Perform a BLAST search against databases (e.g., GenBank non-redundant) and a conserved domain search to confirm NBS identity.

- Classify sequences as TIR- or non-TIR-type based on key residues in conserved motifs, particularly the final amino acid of the kinase-2 motif (TIR-type:

LLVLDDVD; non-TIR-type:LLVLDDVW) [5].

Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Analysis

This process determines the evolutionary relationships between resistance genes [5] [6].

- Sequence Alignment: Extract the NBS domain region from full-length protein sequences. Perform a multiple sequence alignment using tools like MAFFT or ClustalW.

- Tree Construction: Construct a phylogenetic tree using Maximum-Likelihood (e.g., with IQ-TREE or MEGA6) or Parsimony methods. Include sequences from known dicot TNLs and CNLs as references.

- Evolutionary Rate Analysis: For orthologous gene pairs, calculate the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks) using tools like KaKs_Calculator. A Ka/Ks > 1 indicates positive selection.

Visualizing Experimental and Evolutionary Pathways

Workflow for TNL Phylogenetic Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a typical study investigating the presence and evolution of TNL genes, integrating the methodologies described above.

Evolutionary History of TNL and Non-TNL Genes

This diagram summarizes the current understanding of the evolutionary trajectory of NBS-LRR genes in land plants, explaining the observed distribution.

Table 2: Essential Materials for TNL Phylogenetic and Functional Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER Software Suite | Scans protein sequences for NB-ARC and other domains using profile hidden Markov models. | Initial identification of NBS-encoding genes from a whole proteome [14]. |

| Pfam Database | Repository of protein family HMMs (e.g., NB-ARC PF00931, TIR PF01582). | Curated models for domain annotation and gene classification [10] [6]. |

| Degenerate Primers | Amplifies diverse NBS-LRR gene fragments from genomic DNA where sequence info is limited. | Surveying TNL presence/absence across diverse monocot orders [5]. |

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Functional validation tool to knock down candidate gene expression in plants. | Demonstrating the role of a specific NBS gene (GaNBS) in virus resistance [10]. |

| OrthoFinder | Infers orthogroups and gene families from whole proteome data. | Evolutionary analysis of NBS genes across multiple species to identify core and lineage-specific groups [10]. |

| RNA-seq Data | Profiling gene expression under different conditions (tissue, stress). | Identifying NBS-LRR genes upregulated in response to pathogen infection [10] [12]. |

The TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) gene family, one of the largest plant disease resistance gene families, exhibits remarkable evolutionary dynamism across plant lineages. Through comparative genomic analyses, researchers have uncovered that independent duplication and loss events are the primary drivers of the diverse evolutionary patterns observed in this gene family. This guide synthesizes experimental data and bioinformatics methodologies to objectively compare the expansion and contraction of TNL genes across multiple plant species, particularly within the economically important Rosaceae family. The findings reveal that lineage-specific evolutionary pressures have shaped distinct TNL repertoires, influencing species' adaptive immune capacities against rapidly evolving pathogens.

Plant nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes constitute one of the largest and most variable gene families in plants, playing crucial roles in pathogen recognition and defense activation [1]. These genes are categorized into subfamilies based on their N-terminal domains, with TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) and CC-NBS-LRR (CNL) representing the two major classes [1] [16]. TNL genes are characterized by the presence of a Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain at the N-terminus, which is involved in signal transduction during immune responses [17] [1].

The evolution of NBS-LRR genes follows a birth-and-death model characterized by frequent gene duplications and losses, resulting in significant variation in gene number and composition across species [1]. This dynamic evolutionary process generates the diversity needed for plants to recognize rapidly evolving pathogens. Lineage-specific expansions and contractions of TNL genes reflect adaptation to distinct pathogenic environments and contribute to species-specific resistance mechanisms [18] [19].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of TNL gene family evolution across plant lineages, with emphasis on methodological approaches, quantitative expansion/contraction patterns, and functional implications for disease resistance breeding.

Methodological Framework: Analyzing Gene Family Evolution

Core Bioinformatics Pipeline

Genome-wide identification of TNL genes follows a standardized bioinformatics workflow combining multiple complementary approaches:

Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Searches: The NB-ARC domain (PF00931) from Pfam database serves as the primary query to identify candidate NBS-LRR genes using HMMER software with expectation values (E-value) typically set at < 1.0 or more stringent thresholds (< 1e-20) [18] [3]. Additional searches employ TIR (PF01582), CC, and LRR domain models.

Domain Verification and Classification: Candidate genes undergo further validation using PfamScan, NCBI-CDD, and SMART tools to confirm domain architecture [17] [18] [6]. TNL classification requires presence of TIR, NBS, and LRR domains. Genes are categorized based on domain combinations into TNL, TN, CNL, CN, NL, and N types [3].

Manual Curation and Redundancy Removal: Redundant hits from different search methods are consolidated, and sequences are manually verified to ensure complete domain architecture and remove fragments [6].

Table 1: Key Bioinformatics Tools for TNL Identification and Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Search | HMMER v3.1, PfamScan | Identify conserved domains | E-value < 1.0 to < 1e-20 |

| Domain Verification | SMART, NCBI-CDD, Pfam | Confirm domain architecture | E-value < 0.01 |

| Motif Identification | MEME Suite | Discover conserved motifs | Maximum motifs: 10-20 |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | IQ-TREE, MEGA7, OrthoFinder | Construct evolutionary trees | Bootstrap replicates: 1000 |

| Gene Cluster Analysis | MCScanX, TBtools | Identify tandem duplications | Window size: 100-200 kb |

Evolutionary Analysis Methods

Several computational approaches enable quantitative assessment of TNL gene family evolution:

Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Multiple sequence alignment of NBS domains using MAFFT followed by phylogenetic tree construction with IQ-TREE or MEGA7 using maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replicates [6] [3].

Orthogroup Analysis: OrthoFinder implementation using DIAMOND for sequence similarity searches and MCL clustering algorithm to identify groups of orthologous genes across species [10].

Synonymous (Ks) and Non-synonymous (Ka) Substitution Analysis: Calculation of Ka/Ks ratios (ω) using codeML or similar methods to detect selection pressures, with ω < 1 indicating purifying selection, ω = 1 indicating neutral evolution, and ω > 1 indicating positive selection [19] [6].

Gene Cluster Identification: Physical clustering defined as at least two NLR genes located within 200 kb region and separated by no more than eight non-NLR genes [6].

The following diagram illustrates the core bioinformatics workflow for TNL gene identification and evolutionary analysis:

Comparative Evolutionary Patterns Across Plant Lineages

TNL Distribution Across Major Plant Groups

The presence and abundance of TNL genes varies dramatically across plant lineages, reflecting distinct evolutionary trajectories:

Monocots vs. Dicots: Comprehensive analyses across multiple monocot orders (Poales, Zingiberales, Arecales, Asparagales, and Alismatales) reveal a conspicuous absence of TNL genes in monocots, while they are prevalent in dicots and gymnosperms [5]. This suggests significant loss of TNLs in the monocot lineage, with retention of only non-TNL types.

Basal Angiosperms: TNL sequences are present in basal angiosperms like Amborella trichopoda and Nuphar advena, indicating that TNL genes were present in early land plants but underwent significant reduction in monocots and magnoliids [5].

Species-Specific Patterns: Within dicot families, substantial variation in TNL abundance exists. For example, pepper (Capsicum annuum) contains only 4 TNL genes among 252 NBS-LRR genes [16], while apple possesses 219 TNL genes out of 748 NBS-LRR genes [19].

Table 2: Evolutionary Patterns of NBS-LRR Genes Across Plant Lineages

| Plant Group/Species | Total NLR Genes | TNL Count (%) | CNL Count (%) | Evolutionary Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocots (general) | Variable | 0 (0%) | Majority | TNL gene loss |

| Basal Angiosperms | Limited data | Present | Present | Ancestral retention |

| Rosaceae (family) | 2188 | 26 ancestral | 69 ancestral | Independent duplication/loss |

| Apple (M. domestica) | 748 | 219 (29.3%) | 529 (70.7%) | "Continuous expansion" |

| Strawberry (F. vesca) | 144 | 23 (16.0%) | 121 (84.0%) | "Expansion, contraction, re-expansion" |

| Peach (P. persica) | 354 | 128 (36.2%) | 226 (63.8%) | "Early expansion, abrupt shrinking" |

| Pepper (C. annuum) | 252 | 4 (1.6%) | 248 (98.4%) | Strong TNL contraction |

| Tobacco (N. benthamiana) | 156 | 5 (3.2%) | 151 (96.8%) | TNL contraction |

Expansion and Contraction Patterns in Rosaceae

The Rosaceae family provides an excellent model for studying TNL evolution due to available genomes from diverse species and varying life histories (herbaceous vs. woody perennial). Research encompassing 12 Rosaceae genomes identified 2188 NBS-LRR genes, with evolutionary analysis revealing 26 ancestral TNL genes and 69 ancestral CNL genes that underwent independent duplication and loss events during Rosaceae diversification [18].

Distinct evolutionary patterns have been characterized across Rosaceae species:

Rosa chinensis exhibits a "continuous expansion" pattern, with recent duplications significantly contributing to TNL gene numbers [18].

Fragaria vesca (woodland strawberry) shows a "expansion followed by contraction, then a further expansion" pattern [18]. Strawberry contains relatively few TNL genes (23 out of 144 NBS-LRR genes, or 16%) compared to other Rosaceae species [19].

Three Prunus species (peach, mei, apricot) and three Maleae species (apple, pear) shared a "early sharp expanding to abrupt shrinking" pattern [18].

Rubus occidentalis, Potentilla micrantha, Fragaria iinumae and Gillenia trifoliata displayed a "first expansion and then contraction" evolutionary pattern [18].

A comparative analysis of five Rosaceae fruit species (F. vesca, M. domestica, P. bretschneideri, P. persica, and P. mume) found that species-specific duplication has mainly contributed to NBS-LRR gene expansion, with 61.81% of strawberry, 66.04% of apple, 48.61% of pear, 37.01% of peach, and 40.05% of mei NBS-LRR genes derived from species-specific duplication [19].

The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary relationships and expansion patterns of TNL genes across major plant lineages:

Molecular Evolutionary Dynamics

Evolutionary Rates and Selection Pressures

Comparative analyses of TNL and non-TNL genes reveal distinct evolutionary dynamics:

Faster evolution of TNLs: In four of five Rosaceae species studied, TNLs exhibited significantly greater Ks values and Ka/Ks ratios compared to non-TNLs, suggesting more rapid evolution and stronger selective pressures [19]. Most NBS-LRR genes show Ka/Ks ratios less than 1, indicating evolution primarily under purifying selection [19].

Differential selection between subfamilies: Analysis of eight diploid wild strawberry species revealed a significantly higher number of non-TNLs under positive selection compared to TNLs, indicating their rapid diversification [6]. Non-TNLs also demonstrated shorter gene structures and higher expression levels than TNLs [6].

Domain-specific selection: The LRR domain exhibits evidence of diversifying selection with elevated ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous nucleotide substitutions, particularly in solvent-exposed residues of β-sheets, suggesting adaptation for pathogen recognition [1]. In contrast, the NBS domain is subject to purifying selection but not frequent gene-conversion events [1].

Genomic Distribution and Cluster Analysis

TNL genes display non-random genomic distribution patterns that influence their evolution:

Gene clustering: In pepper, 54% of NBS-LRR genes form 47 physical clusters distributed across all chromosomes, with the highest density on chromosome 3 [16]. Similar clustering patterns are observed in apple, with clusters often containing members from the same gene subfamily, though some clusters contain genes from different subfamilies [16].

Tandem duplications: In Rosaceae species, tandem duplications represent a major mechanism for NBS-LRR gene expansion. Apple possesses the highest number of gene families (107) while strawberry has the fewest (12) [19]. The proportion of multi-gene families correlates with species-specific duplication rates.

Chromosomal distribution: Analysis of Perilla citriodora 'Jeju17' revealed 535 NBS-LRR genes with clusters on chromosomes 2, 4, and 10, while a unique RPW8-type R-gene was located on chromosome 7 [20]. This uneven distribution reflects the localized nature of gene duplication events.

Functional Correlations and Experimental Validation

Expression Profiling and Disease Resistance

Functional studies connecting TNL evolution to disease resistance outcomes:

In Rosa chinensis, transcriptome analysis revealed that RcTNL genes were dominantly expressed in leaves and responded to hormones (gibberellin, jasmonic acid, salicylic acid) and fungal pathogens (Botrytis cinerea, Podosphaera pannosa, and Marssonina rosae) [17]. RcTNL23 showed significant upregulation in response to three hormones and three pathogens, suggesting its importance in disease resistance [17].

In wild strawberries, species with higher proportions of non-TNLs (Fragaria pentaphylla and Fragaria nilgerrensis) exhibited significantly greater resistance to Botrytis cinerea compared to Fragaria vesca, which has the lowest proportion of non-TNLs [6]. This correlation suggests non-TNLs contribute substantially to pathogen defense despite the emphasis on TNL evolution in many studies.

Functional validation via virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of GaNBS (OG2) in resistant cotton demonstrated its putative role in virus titering, providing experimental evidence for the functional importance of specific NBS genes in disease resistance [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for TNL Evolutionary Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Example | Application in TNL Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Databases | Genome Database for Rosaceae (GDR), Phytozome, NCBI | Source of genome sequences and annotations for comparative analysis |

| Domain Databases | Pfam, SMART, NCBI-CDD | Identification and verification of TIR, NBS, LRR domains |

| HMM Profiles | NB-ARC (PF00931), TIR (PF01582) | Hidden Markov Models for domain identification |

| Sequence Alignment | MAFFT, ClustalW | Multiple sequence alignment for phylogenetic analysis |

| Phylogenetic Software | IQ-TREE, MEGA7, OrthoFinder | Evolutionary relationship reconstruction |

| Motif Discovery | MEME Suite | Identification of conserved protein motifs |

| Gene Cluster Analysis | MCScanX, TBtools | Identification of tandem duplications and syntenic regions |

| Expression Databases | IPF Database, CottonFGD | Tissue-specific and stress-responsive expression patterns |

| Functional Validation | VIGS (Virus-Induced Gene Silencing) | Experimental verification of gene function in disease resistance |

The evolutionary patterns of TNL gene families demonstrate remarkable lineage-specificity, driven primarily by species-specific duplication and loss events. The comparative analysis presented here reveals that:

Evolutionary trajectories are highly lineage-dependent, with some species exhibiting continuous expansion (Rosa chinensis), while others show patterns of expansion and contraction (Fragaria vesca) or early expansion followed by abrupt shrinking (Prunus species).

Differential evolution between TNL and CNL subfamilies is evident across multiple plant families, with TNLs generally evolving faster in Rosaceae species but being completely lost in monocot lineages.

Functional correlations exist between evolutionary patterns and disease resistance, with species-specific TNL expansions potentially enhancing adaptive immunity to localized pathogen pressures.

Future research directions should include more comprehensive functional characterization of lineage-specific TNL clusters, investigation of the mechanisms driving TNL loss in monocots, and exploration of how evolutionary patterns translate to functional diversity in pathogen recognition. The integration of pan-genomic approaches will further refine our understanding of TNL gene family evolution and its implications for developing disease-resistant crops through informed breeding strategies.

Structural variations (SVs) represent a class of genomic alterations involving segments of DNA that are 50 base pairs or larger, including insertions, deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations [21] [22] [23]. In plant genomes, these large-scale genomic rearrangements are now recognized as a major driver of genetic diversity, influencing phenotypes ranging from disease resistance to environmental adaptation [22] [23]. Among the most significant functional outcomes of structural variation in plants is the creation of diverse domain architectures within nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes, which constitute the largest family of plant disease resistance genes [10] [24].

The NBS-LRR genes (also called NLR genes) encode modular proteins typically composed of three fundamental domains: an variable N-terminal domain, a central nucleotide-binding adaptor (NBS or NB-ARC) domain, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) region [10] [6]. These genes are categorized into distinct subfamilies based on their N-terminal domains: TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) containing a Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain, CC-NBS-LRR (CNL) containing a coiled-coil domain, and RPW8-NBS-LRR (RNL) containing a Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8 domain [10] [6] [25]. The structural variation affecting these genes creates remarkable diversity in domain arrangements, encompassing both classical architectures that are widely conserved across plant lineages and species-specific configurations that may confer specialized resistance capabilities [10].

Recent studies have revealed that structural variations affecting NBS-LRR genes can substantially alter gene function through several mechanisms: changing gene dosage via copy number variations, creating novel chimeric genes through fusion events, interrupting functional domains, or modifying regulatory sequences that control gene expression [22]. This comprehensive analysis examines the spectrum of classical and species-specific domain arrangements resulting from structural variation, their distribution across plant lineages, functional implications for disease resistance, and the experimental approaches used to characterize them.

Classical Domain Architectures and Evolutionary Patterns

Classical NBS-LRR domain architectures represent the conserved structural patterns observed across multiple plant families. Large-scale comparative genomic analyses have identified several such architectures that form the core of the plant immune receptor repertoire. A recent pan-species investigation identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species ranging from mosses to monocots and dicots, classifying them into 168 distinct architectural classes [10]. Among these, several classical patterns emerged, including NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS, TIR-NBS-LRR, CC-NBS, and CC-NBS-LRR [10].

The evolutionary distribution of these classical architectures reveals significant patterns across plant lineages. TNL-type genes are present in bryophytes, gymnosperms, and eudicots, but are notably rare or absent in most monocots [5]. Research examining five monocot orders (Poales, Zingiberales, Arecales, Asparagales, and Alismatales) found no TIR-NBS-LRR sequences, suggesting that although these sequences were present in early land plants, they have been significantly reduced in monocots and magnoliids [5]. In contrast, CNL-type genes appear across all major plant lineages, including monocots, suggesting their fundamental conservation in plant immunity [5] [6].

Table 1: Distribution of Classical NBS-LRR Domain Architectures Across Major Plant Lineages

| Domain Architecture | Bryophytes | Gymnosperms | Monocots | Eudicots | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) | Present [5] | Present [5] | Rare/Absent [5] | Present [5] [6] | TIR domain mediates signaling; homogeneous sequences [5] |

| CC-NBS-LRR (CNL) | Present | Present | Present [5] [6] | Present [6] [24] | CC domain; heterogeneous sequences form multiple clades [5] |

| RPW8-NBS-LRR (RNL) | Information Limited | Information Limited | Present [25] | Present [6] | RPW8 domain; helper function in immunity [6] |

| NBS-LRR (NL) | Present | Present | Present | Present | Lacks distinctive N-terminal domain [24] |

The structural conservation within these classical architectures is maintained by specific functional constraints. The central NBS domain contains highly conserved motifs including the P-loop, GLPL, MHD, and Kinase-2 motifs, which are critical for nucleotide binding and hydrolysis [10] [25]. The Kinase-2 motif is particularly noteworthy as its final amino acid residue serves as a diagnostic feature for classifying NBS sequences as TIR-type (typically ending with aspartic acid) or non-TIR-type (typically ending with tryptophan) [5]. The LRR domains, while more variable, provide specificity in pathogen recognition through protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions [24] [26].

Table 2: Conserved Motifs in Classical NBS Domain Architectures

| Motif Name | Consensus Sequence | Functional Role | Location in NBS Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-loop | Not specified in sources | Nucleotide binding | N-terminal region |

| Kinase-2 | TIR: LLVLDDVD; non-TIR: LLVLDDVW [5] | Hydrolytic function | Central region |

| RNBS-A | TIR: FLENIRExSKKHGLEHLQKKLLSKLL; non-TIR: FDLxAWVCVSQxF [5] | Structural stability | Between P-loop and Kinase-2 |

| RNBS-D | TIR: FLHIACFF; non-TIR: CFLYCALFPED [5] | Structural stability | Between Kinase-2 and MHD |

| MHD | Not specified in sources | Regulation of nucleotide state | C-terminal region |

| GLPL | Not specified in sources | Structural role | C-terminal region |

Species-Specific Domain Arrangements and Novel Architectures

Beyond the classical architectures, numerous species-specific and novel domain arrangements have emerged through lineage-specific structural variations, expanding the functional repertoire of plant immune receptors. These unusual configurations often arise from domain shuffling, fusion events, and the gain or loss of protein domains [10].

In cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea cv. Tifrunner), researchers identified an unusual TIR-CC-NBS-LRR architecture where both TIR and CC domains coexist in 26 NBS-LRR proteins [26]. This configuration is particularly noteworthy because TNL and CNL genes were previously thought to have distinct evolutionary origins, and no sequences containing both TIR and CC domains were found in the diploid ancestors (A. duranensis and A. ipaensis) of cultivated peanut [26]. This suggests that genetic exchange or gene rearrangement following tetraploidization facilitated the fusion of these typically distinct domains. Additionally, three sequences were found to contain NBS-WRKY fusion proteins, where an NBS domain is combined with a WRKY transcription factor domain, potentially creating direct pathways from pathogen recognition to transcriptional regulation [26].

The comprehensive analysis across 34 plant species revealed several striking species-specific domain patterns, including TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, and Sugartr-NBS architectures [10]. These unusual configurations demonstrate how structural variation can create novel gene fusions that potentially connect pathogen recognition with diverse biochemical functions. For instance, the fusion of NBS domains with Cupin1 domains (associated with metabolic enzymes) or Prenyltransf domains (involved in prenylation reactions) may represent mechanisms for directly linking pathogen detection with metabolic responses [10].

In the tung tree (Vernicia species), comparative analysis between susceptible V. fordii and resistant V. montana revealed significant species-specific differences in NBS-LRR domain architectures [24]. While V. fordii completely lacked TIR domains in its NBS-LRR genes, V. montana contained 12 VmNBS-LRRs with TIR domains (8.1% of its total NBS-LRR repertoire), including three TIR-NBS-LRR genes and two CC-TIR-NBS genes with both CC and TIR domains [24]. This discrepancy suggests that lineage-specific domain loss events may contribute to differences in disease susceptibility between related species.

Table 3: Notable Species-Specific Domain Arrangements in Plant NBS-LRR Genes

| Species | Novel Domain Architecture | Potential Functional Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple species | TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1 | Links pathogen recognition with metabolic functions via Cupin domain [10] | [10] |

| Multiple species | TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf | Connects pathogen sensing with prenylation pathways [10] | [10] |

| Multiple species | Sugar_tr-NBS | Fuses sugar transporter domain with NBS domain [10] | [10] |

| Arachis hypogaea (peanut) | TIR-CC-NBS-LRR | Fusion of two normally distinct N-terminal domains [26] | [26] |

| Arachis hypogaea (peanut) | NBS-WRKY | Direct coupling of pathogen recognition and transcriptional regulation [26] | [26] |

| Vernicia montana (tung tree) | CC-TIR-NBS | Combination of CC and TIR domains in resistant species [24] | [24] |

The functional implications of these novel architectures remain largely unexplored, but they represent fascinating evolutionary experiments in plant immunity. The fusion of NBS domains with various functional domains may create receptors with integrated recognition and response capabilities, potentially enabling more rapid or specialized defense reactions against pathogens.

Comparative Genomic Analyses and Detection Methodologies

The identification and characterization of structural variations in NBS-LRR genes relies on sophisticated bioinformatic pipelines and comparative genomic approaches. This section outlines the key methodological frameworks and analytical techniques used to detect and classify classical and species-specific domain arrangements.

Genome-Wide Identification of NBS-LRR Genes

The standard pipeline for comprehensive identification of NBS-LRR genes combines multiple complementary approaches to ensure sensitive detection while minimizing false positives [10] [6] [25]. The typical workflow begins with Hidden Markov Model (HMM) searches using the conserved NB-ARC domain (Pfam: PF00931) as a query against proteome or genome datasets, often with an E-value cutoff of < 1e-5 [10] [6] [25]. This is complemented by BLAST-based searches using reference NLR protein sequences from well-characterized species such as Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, or related taxa, applying stringent E-value cutoffs (typically 1e-10) [6] [25]. Candidate sequences identified through these methods are then subjected to domain architecture validation using tools like InterProScan, NCBI's Batch CD-Search, or SMART to confirm the presence and arrangement of NBS, TIR, CC, RPW8, and LRR domains [6] [24] [25]. Additional domains are identified through similar domain-based searches against Pfam and related databases [10].

Orthogroup Analysis and Evolutionary Comparisons

To understand the evolutionary relationships of NBS-LRR genes across species, researchers employ orthogroup analysis using tools such as OrthoFinder [10] [25]. This approach clusters genes into orthogroups (OGs) representing groups of genes descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor. A comprehensive study identified 603 orthogroups across 34 plant species, with some core orthogroups (e.g., OG0, OG1, OG2) being widely distributed across multiple species, while unique orthogroups (e.g., OG80, OG82) were highly specific to particular lineages [10]. This analysis helps distinguish evolutionarily conserved NBS-LRR genes from those that have undergone lineage-specific expansion or diversification.

Identification of Gene Clusters and Tandem Duplications

NBS-LRR genes frequently exhibit clustered genomic arrangements, often resulting from tandem duplication events [6] [25]. Computational identification of these clusters typically defines them as genomic regions where at least two NLR genes are located within 200 kilobases of each other and separated by no more than eight non-NLR genes [6]. The MCScanX algorithm is commonly used to identify tandem and segmental duplications, with visualization tools like TBtools enabling chromosomal mapping of these arrangements [6] [25]. These analyses have revealed that different plant species exhibit substantial variation in their cluster organizations, with some species showing extensive tandem arrays of related NBS-LRR genes while others display more dispersed genomic distributions [10] [24].

Structural Variation Detection Methods

Advanced sequencing technologies and specialized computational approaches are required to detect the full spectrum of structural variations affecting NBS-LRR genes [22] [23]. Long-read sequencing technologies (such as PacBio HiFi sequencing) generate reads of 10-20 kb with high accuracy (Q30+), enabling the resolution of complex genomic regions that are often enriched for NBS-LRR genes [23]. Read-depth methods identify copy number variations (deletions and duplications) by detecting deviations from expected coverage distributions [22] [23]. Split-read approaches identify breakpoints of structural variations by detecting reads that split across rearrangement junctions [22]. Assembly-based methods construct complete genomes or genomic regions de novo and compare them to reference sequences to identify structural differences [22] [23]. For validation, PCR-based methods including quantitative PCR (for copy number validation) and breakpoint-specific PCR (for junction validation) provide orthogonal confirmation of predicted structural variants [22].

Experimental Validation and Functional Characterization

Beyond computational identification, experimental approaches are essential for validating the functional significance of structural variations in NBS-LRR genes. Several well-established methodologies enable researchers to connect genomic variations with phenotypic outcomes in disease resistance.

Expression Profiling Under Stress Conditions

Transcriptomic analyses through RNA sequencing provide critical insights into the functional roles of NBS-LRR genes with different domain architectures. Standard approaches involve treating plants with various biotic (fungal, bacterial, or viral pathogens) and abiotic (drought, salt, temperature) stresses, then extracting RNA from different tissues at multiple time points for sequencing [10]. The resulting data are processed through transcriptomic pipelines to calculate expression values (typically FPKM or TPM), which are then visualized as heatmaps to identify differentially expressed NBS-LRR genes [10]. For example, expression profiling in cotton identified putative upregulation of specific orthogroups (OG2, OG6, and OG15) in different tissues under various biotic and abiotic stresses in plants with varying susceptibility to cotton leaf curl disease [10].

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

VIGS has emerged as a powerful tool for functional characterization of NBS-LRR genes. This approach uses modified viruses to deliver gene-specific sequences that trigger RNA interference and silence target genes [10] [24]. The standard protocol involves: (1) Target Selection - identifying a unique gene segment (typically 200-500 bp) specific to the NBS-LRR gene of interest; (2) Vector Construction - cloning the target segment into a VIGS vector (such as TRV-based vectors); (3) Plant Inoculation - introducing the vector into plants through agrobacterium-mediated infiltration or in vitro transcription; and (4) Phenotypic Assessment - challenging silenced plants with pathogens and evaluating disease symptoms compared to controls [10] [24]. For instance, silencing of GaNBS (from orthogroup OG2) in resistant cotton demonstrated its putative role in reducing virus titers [10]. Similarly, VIGS of Vm019719 in resistant Vernicia montana compromised its resistance to Fusarium wilt, confirming this NBS-LRR gene's critical role in disease resistance [24].

Genetic Variation Analysis Between Resistant and Susceptible Genotypes

Comparing genetic sequences between resistant and susceptible varieties can identify structural variations correlated with disease resistance phenotypes. This typically involves whole-genome sequencing of multiple accessions with contrasting resistance phenotypes, followed by variant calling to identify polymorphisms (SNPs, indels, and structural variants) specifically associated with resistance [10] [24]. For example, comparison between susceptible (Coker 312) and tolerant (Mac7) Gossypium hirsutum accessions identified several unique variants in NBS genes of Mac7 (6,583 variants) and Coker312 (5,173 variants) [10]. Further analysis can reveal how these variations affect functional domains, gene expression, or protein function.

Protein-Ligand and Protein-Protein Interaction Studies

Understanding how different domain architectures influence molecular interactions is crucial for deciphering NBS-LRR function. Protein-ligand interaction studies examine how NBS domains bind nucleotides (ADP/ATP) and how structural variations affect nucleotide binding and hydrolysis [10]. Protein-protein interaction assays (such as yeast two-hybrid, co-immunoprecipitation, or surface plasmon resonance) investigate how LRR domains interact with pathogen effectors or host proteins, and how alternative domain arrangements affect these interactions [10] [24]. For example, interaction studies in cotton showed strong binding of certain NBS proteins with ADP/ATP and different core proteins of the cotton leaf curl disease virus [10].

Table 4: Key Experimental Approaches for Validating NBS-LRR Gene Function

| Method | Key Applications | Typical Workflow | Interpretative Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Profiling | Identify stress-responsive NLR genes; Compare expression in resistant vs. susceptible varieties [10] | RNA extraction from stressed tissues → RNA-seq library preparation → Sequencing → Differential expression analysis [10] | Expression changes may be tissue-specific or temporal; Correlation ≠causation |

| VIGS | Functional validation of specific NLR genes; Assess role in disease resistance [10] [24] | Target selection → Vector construction → Plant inoculation → Pathogen challenge → Phenotyping [10] [24] | Silencing efficiency varies; Potential off-target effects; Developmental impacts |

| Genetic Variation Analysis | Identify polymorphisms associated with resistance; Detect presence/absence variations [10] [24] | WGS of multiple accessions → Variant calling → Association with phenotypes [10] [24] | Requires adequate sample size; Population structure can confound associations |

| Interaction Studies | Characterize binding partners; Understand signaling mechanisms [10] | Recombinant protein expression → Interaction assays (Y2H, Co-IP, SPR) → Data analysis [10] | In vitro conditions may not reflect in vivo context; Transient vs. stable interactions |

Research on structural variations in NBS-LRR genes relies on specialized bioinformatic tools, experimental reagents, and genomic resources. The following table summarizes key solutions that enable comprehensive analysis in this field.

Table 5: Essential Research Resources for Analyzing Structural Variations in NBS-LRR Genes

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatic Tools | HMMER [10] [6] [25]; OrthoFinder [10] [25]; MCScanX [6] | Domain identification; Orthogroup analysis; Gene duplication detection | HMMER uses Pfam models (e.g., NB-ARC: PF00931); OrthoFinder uses DIAMOND for sequence similarity [10] |

| Domain Databases | Pfam [10] [6]; InterPro [25]; SMART [6] | Protein domain annotation and classification | Pfam provides HMM profiles; CD-search verifies domain presence [10] [6] |

| Genomic Resources | Plaza Genome Database [10]; Phytozome [10]; NCBI Genome [10] | Source of genome assemblies and annotations | Multi-species comparisons require standardized annotations [10] |

| VIGS Vectors | TRV-based vectors [10] [24] | Functional gene silencing in plants | TRV1 and TRV2 systems; Agrobacterium delivery [10] [24] |

| Expression Analysis | IPF Database [10]; CottonFGD [10]; PlantCARE [6] | Tissue-specific expression data; Promoter element analysis | PlantCARE identifies cis-elements in promoters [6] |

| Population Genomics | DGV [22]; gnomAD-SV [22]; dbVAR [22] | Structural variation frequency in populations | Distinguish pathogenic SVs from polymorphisms [22] |

The comprehensive analysis of structural variations in NBS-LRR genes reveals a complex landscape of both highly conserved classical architectures and evolutionarily dynamic species-specific arrangements. The classical TNL, CNL, and RNL configurations represent the core immune receptors maintained across broad evolutionary timescales, while novel domain arrangements resulting from recent structural variations provide raw material for evolutionary innovation in pathogen recognition [10] [6] [24].

This duality has important implications for both basic plant immunity research and applied crop improvement strategies. From a fundamental perspective, the conservation of classical architectures across diverse plant lineages underscores their essential role in core immune signaling mechanisms. Meanwhile, the discovery of species-specific arrangements highlights the remarkable plasticity of plant genomes in generating structural diversity to confront evolving pathogen populations [10] [26]. The functional characterization of these varied architectures through integrated computational and experimental approaches continues to reveal new mechanisms of pathogen recognition and defense signaling.

For crop improvement, understanding structural variations in NBS-LRR genes provides valuable insights for marker-assisted breeding and genetic engineering strategies. The identification of specific domain arrangements associated with disease resistance in crop wild relatives offers potential targets for introgression into cultivated varieties [24] [25]. Furthermore, documenting the erosion of NBS-LRR diversity during domestication—as observed in asparagus, where gene counts decreased from 63 NLR genes in wild A. setaceus to just 27 in cultivated A. officinalis—informs conservation strategies for maintaining genetic diversity in breeding programs [25].

As sequencing technologies continue to advance, particularly with the widespread adoption of long-read sequencing that effectively resolves complex repetitive regions, our understanding of structural variations in NBS-LRR genes will undoubtedly expand [22] [23]. Future research integrating pangenome references, multi-omics data, and advanced functional characterization will further illuminate how classical and species-specific domain architectures collectively contribute to plant disease resistance in natural and agricultural ecosystems.

TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) proteins constitute a major class of intracellular immune receptors that enable plants to detect pathogen effectors and initiate robust defense responses. Understanding the diversity, distribution, and evolution of these genes across the plant kingdom is fundamental to plant pathology and resistance breeding. This guide provides a comparative analysis of TNL genes, synthesizing genomic data from diverse species to elucidate patterns of expansion, contraction, and structural variation that define this critical component of the plant immune system.

Comparative Distribution of TNL Genes Across Plant Lineages

Genomic analyses reveal a striking pattern of TNL distribution across plant phylogeny. TNL genes are ubiquitous in dicotyledonous plants but are completely absent from cereal genomes, suggesting lineage-specific loss in monocots [1]. The evolutionary trajectory of TNL genes shows deep origins, with homologs present in non-vascular plants and gymnosperms, though substantial gene expansion occurred primarily in flowering plants [10] [1].

Table 1: Distribution of NBS-LRR Genes Across Representative Plant Species

| Species | Total NBS/NBS-LRR Genes | TNL Genes | CNL/Non-TNL Genes | Key Evolutionary Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 149-167 [27] | ~62 [1] | ~87 | Representative dicot model with both major subfamilies |

| Brassica oleracea | 157 [27] | Not specified | Not specified | Retained TNLs post-divergence from Arabidopsis |

| Brassica rapa | 206 [27] | Not specified | Not specified | Retained TNLs post-divergence from Arabidopsis |

| Fragaria species (diploid strawberries) | 133-325 [28] [6] | Less than non-TNLs (under 50%) [6] | Over 50% of NLR family [6] | Non-TNLs dominate in all eight diploid species studied |

| Oryza sativa (rice) | ~400 [1] | 0 [1] | ~400 | Complete absence of TNLs characteristic of cereals |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | 156 NBS-LRR homologs [3] | 5 TNL-type [3] | 25 CNL-type [3] | Model plant for virology with limited TNL representation |

| Physcomitrella patens (moss) | ~25 [10] | Present [1] | Present [1] | Represents ancestral NLR repertoire in non-vascular plants |

The evolutionary dynamics between TNL and non-TNL genes show notable patterns. In wild strawberries, non-TNLs constitute over 50% of the NLR gene family in all eight diploid species examined, surpassing TNLs in proportion [6]. Expression analyses further indicate that non-TNLs show dominant expression under both normal and infected conditions, with RNLs exhibiting particularly high expression levels [6].

Domain Architecture and Structural Diversity

TNL proteins exhibit a characteristic tripartite domain structure consisting of an N-terminal Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain, a central nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain, and C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) [1]. The TIR domain is involved in signaling, the NBS domain functions as a molecular switch for ATP/GTP binding and hydrolysis, and the LRR domain is responsible for protein-protein interactions and ligand binding [28] [1].

Comparative genomics has uncovered significant diversity in domain architecture beyond the classical TNL structure. A comprehensive study analyzing 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species identified 168 distinct classes with several novel domain architecture patterns [10] [29]. These include:

- Classical architectures: TIR-NBS, TIR-NBS-LRR [10] [29]

- Species-specific structural patterns: TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, and Sugar_tr-NBS [10]

- Truncated variants: TIR-NBS (TN) proteins that lack LRR domains [1]

Table 2: TNL Domain Architecture Variants and Their Functional Implications

| Architecture Type | Domain Composition | Predicted Functional Role | Conservation Across Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length TNL | TIR-NBS-LRR | Canonical pathogen recognition and signaling | Broadly distributed across dicots |

| TN-type | TIR-NBS | Potential adaptors or regulators of signaling | Limited distribution |

| TIR-X | TIR with other domains | Specialized functional adaptations | Often species-specific |

| TNL with integrated domains | TIR-NBS-LRR with additional C-terminal domains | Expanded recognition capabilities | Emerging through lineage-specific evolution |

Structural variations significantly impact function. The LRR domain typically contains 14 repeats on average with 5-10 sequence variants for each repeat, creating immense potential for functional variation - estimated at over 9×10¹¹ variants in Arabidopsis alone [1]. This diversity generates the putative binding surface responsible for pathogen recognition specificity.

Evolution and Genomic Organization

TNL genes evolve through diverse mechanisms that drive their diversification. Phylogenetic analyses reveal that plant NBS-LRR genes are numerous and ancient in origin, with orthologous relationships difficult to determine due to lineage-specific gene duplications and losses [1]. The evolution of TNL genes follows a "birth-and-death" model characterized by several key processes:

- Gene duplication: Both tandem and segmental duplications generate new genetic material for evolution [30]

- Unequal crossing-over: Creates variation in copy number within clusters [1]

- Sequence exchange: Gene conversion and ectopic recombination reshape sequences [30]

- Diversifying selection: Maintains variation in solvent-exposed residues of LRR domains [1]

Genomic organization of TNL genes shows distinct patterns across species. These genes are frequently clustered in plant genomes as a result of both segmental and tandem duplications [1] [30]. In Arabidopsis, NBS-LRR genes are distributed as singletons and clusters, with approximately 40 clusters identified [30]. These clusters can be homogeneous (containing genes from the same phylogenetic lineage) or heterogeneous (containing genes from different lineages) [30].

Selective pressures differ significantly between TNL and CNL gene types. Comparative analysis of Fragaria species demonstrated that Ks and Ka/Ks values of TNLs were significantly greater than those of non-TNLs, suggesting TNLs are more rapidly evolving and driven by stronger diversifying selective pressures [28]. However, in diploid wild strawberries, a significantly higher number of non-TNLs were under positive selection compared to TNLs, indicating their rapid diversification in these specific lineages [6].

Expression Regulation and miRNA Interactions

TNL gene expression is tightly regulated through multiple mechanisms, with microRNAs playing a particularly important role. At least eight families of miRNAs have been described that target NBS-LRRs in plants, with most targeting highly duplicated NBS-LRRs [31]. These miRNAs typically target conserved regions of NBS-LRR genes, allowing one miRNA to regulate multiple lineage members.

Key regulatory patterns include:

- miR482/2118 family: Targets the encoded P-loop region of NBS-LRR genes and is conserved from gymnosperms to dicots [31]

- PhasiRNA production: 22-nt miRNAs trigger phased secondary siRNA production from their target NBS-LRR mRNAs [31]

- Expression plasticity: In cotton, expression profiling revealed upregulation of specific orthogroups (OG2, OG6, OG15) in different tissues under various biotic and abiotic stresses in plants with varying susceptibility to cotton leaf curl disease [10]

The co-evolutionary relationship between miRNAs and NBS-LRRs represents an important regulatory balance. Nucleotide diversity in the wobble position of the codons in the target site drives the diversification of miRNAs, creating a dynamic evolutionary arms race between regulators and their targets [31]. This system may enable plants to maintain extensive NLR repertoires without exhausting functional NLR loci, potentially offsetting fitness costs associated with NLR maintenance [10].

Functional Validation and Disease Resistance Associations

Functional studies provide critical evidence linking TNL diversity to disease resistance phenotypes. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of GaNBS (OG2) in resistant cotton demonstrated its putative role in virus tittering, directly validating the function of specific TNL orthogroups in pathogen defense [10] [29]. Protein-ligand and protein-protein interaction analyses further showed strong interactions of putative NBS proteins with ADP/ATP and different core proteins of the cotton leaf curl disease virus [10].

Resistance correlations are evident across plant species:

- In wild strawberries, Fragaria pentaphylla and Fragaria nilgerrensis with the highest proportion of non-TNLs exhibited significantly greater resistance to Botrytis cinerea compared to Fragaria vesca with the lowest proportion of non-TNLs [6]

- Genetic variation analysis between susceptible (Coker 312) and tolerant (Mac7) Gossypium hirsutum accessions identified several unique variants in NBS genes, with Mac7 displaying 6,583 variants compared to 5,173 in Coker312 [10]

- Expression profiling of NBS-LRR genes in Fragaria species revealed that the same gene expressed differently under different genetic backgrounds in response to pathogens [28]

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

Genome-wide identification of TNL genes relies on established bioinformatic protocols and experimental reagents. The following toolkit represents essential resources for TNL gene family analysis:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for TNL Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Application | Function/Utility | Example Sources/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMMER Suite | Domain identification | Identifies NB-ARC domains (PF00931) using hidden Markov models | [10] [28] [27] |

| Pfam Database | Domain verification | Curated database of protein domains and families | [28] [27] [3] |

| OrthoFinder | Orthogroup analysis | Determines orthologous groups across species | [10] |

| MEME Suite | Motif discovery | Identifies conserved protein motifs | [6] [3] |

| SMART/CDD | Domain validation | Verifies domain predictions and boundaries | [28] [6] |

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Functional validation | Assesses gene function through silencing | [10] [29] [3] |

| DIAMOND/MCL | Sequence similarity/clustering | Fast sequence similarity and clustering algorithms | [10] |

| RNA-seq Expression Profiling | Expression analysis | Determines differential expression under stress | [10] [6] |

Standardized methodologies have emerged for comprehensive TNL analysis:

- Sequence Identification: HMMER searches with NB-ARC domain (PF00931) followed by manual curation [10] [27]

- Domain Architecture Classification: PfamScan, SMART, and COILS analyses for TIR, CC, and LRR domains [10] [28]

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Multiple sequence alignment with MAFFT or ClustalW followed by Maximum Likelihood tree construction [10] [6]

- Evolutionary Analysis: Orthogroup clustering, Ka/Ks calculations, and duplication pattern identification [10] [6]

- Expression Profiling: RNA-seq data analysis across tissues and stress conditions [10] [6]

Comparative genomics of TNL genes across plant kingdoms reveals a dynamic evolutionary landscape shaped by lineage-specific expansions, contractions, and diversifying selection. The distribution of TNL genes demonstrates profound lineage-specific patterns, with complete absence in cereals contrasting with substantial diversity in dicots. Structural analyses uncover both conserved architectures and innovative domain combinations that expand functional capabilities. The regulation of TNLs through miRNA interactions represents a critical layer of control that balances defense efficacy with fitness costs. Functional studies continue to validate the role of specific TNL orthogroups in pathogen recognition and defense signaling. These insights provide a foundation for leveraging TNL diversity in crop improvement programs and understanding the fundamental principles of plant immunity evolution.

Computational Approaches for TNL Identification and Classification

Genome-wide screening for protein domains is a fundamental methodology in bioinformatics, enabling researchers to annotate gene function and understand evolutionary relationships across species. Among the most powerful techniques for this purpose are profile Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), which provide a probabilistic framework for modeling multiple sequence alignments of protein families and detecting remote homologies that simpler methods might miss [32] [33]. The HMMER software package, developed by Sean Eddy, has emerged as a de facto standard for this type of analysis, serving as the computational engine for major protein domain databases including Pfam, TIGRFAMs, and SMART [32] [33]. The critical importance of these tools is particularly evident in specialized research domains such as the study of TIR-NBS-LRR domain architectures, where accurate identification of these disease resistance genes in plants provides crucial insights into innate immune mechanisms and potential applications in crop improvement [13] [34] [6].

This comparison guide objectively evaluates HMMER's performance against alternative profile HMM implementations, with particular focus on its application in plant genomics research. We examine experimental data from comparative studies, analyze critical algorithmic differences that impact performance, and provide detailed protocols for conducting genome-wide screens for TIR-NBS-LRR genes and other important protein domains. The guidance presented here will equip researchers with the necessary knowledge to select appropriate tools and methodologies for their specific domain analysis requirements, with special consideration for the challenges inherent in large-scale genomic studies.

HMMER Versus Alternative Profile HMM Tools

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

The landscape of profile HMM tools has been dominated by two main packages: HMMER and SAM (Sequence Alignment and Modeling System). Multiple independent studies have systematically compared their performance using standardized datasets and metrics, with results consistently highlighting a fundamental trade-off between sensitivity and accuracy in their default configurations.

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison Between HMMER and SAM

| Performance Metric | HMMER | SAM | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Sensitivity | Lower | Superior | SCOP/Pfam-based test set with local and global HMM scoring [32] |

| Model Estimation | Inferior | Superior | Built from identical multiple sequence alignments [32] [33] |

| Model Scoring Accuracy | More accurate | Less accurate | Evaluation of scoring algorithms against known structures [32] |

| Alignment Quality Dependency | High | High | Quality of input multiple alignment is the most critical performance factor [33] |

| Automated Alignment Generation | Lacks equivalent | SAM T99 script available | Iterative database search similar to PSI-BLAST [33] |

| Execution Speed | 1-3x faster on databases >2000 sequences | Faster on smaller databases | Benchmarking tests with varying database sizes [33] |

Comparative analyses reveal that SAM's model estimation capabilities generally produce more sensitive models, while HMMER's scoring algorithms provide more accurate E-values and better discrimination between true and false positives [32]. This performance difference stems primarily from how each package handles the balance between observed sequence counts and prior probabilities during model construction. SAM's implementation gives more weight to prior probabilities, which proves particularly advantageous when working with limited sequence data, whereas HMMER places greater emphasis on the actual sequence counts in the input alignment [32].

In practical applications, researchers have successfully employed HMMER for genome-wide identification of NBS-LRR genes across numerous plant species. For example, studies in Nicotiana benthamiana identified 156 NBS-LRR homologs using HMMER with an E-value cutoff of < 1×10â»Â²â° [3], while investigations of Arachis hypogaea cv. Tifrunner discovered 713 full-length NBS-LRRs using similar HMMER-based approaches [26]. These implementations demonstrate HMMER's robustness for large-scale genomic surveys, particularly when appropriate domain thresholds and verification steps are implemented.

Algorithmic and Implementation Differences

The performance disparities between HMMER and SAM originate from fundamental differences in their underlying algorithms and architectural decisions:

HMM Architecture: HMMER utilizes a 7-transition model that forbids transitions from insert to delete states and vice versa, while SAM maintains the original 9-transition architecture that allows all possible transitions between states [32]. This architectural variation impacts how each model handles indels and affects the overall model flexibility.

Prior Probabilities: Both packages employ Dirichlet mixtures for modeling emission prior probabilities, but SAM defaults to a 20-component mixture compared to HMMER's 9-component mixture, providing potentially more nuanced handling of amino acid conservation patterns [32]. For transition priors, SAM assigns higher probabilities to insertions and deletions, which may contribute to its increased sensitivity in detecting remote homologs.

Sequence Weighting: The two packages employ different algorithms for calculating relative sequence weights—HMMER uses tree-based weighting while SAM implements an unpublished relative entropy-based method—though studies have shown their relative weighting schemes perform equivalently [32]. However, they differ significantly in how they calculate the total weight (effective sequence number), which governs the balance between observed sequence counts and prior probabilities.

Technical Implementation: HMMER is open-source and operates under the GNU General Public License, while SAM is free for academic use but not open source [33]. This distinction has practical implications for customization and integration into larger analysis pipelines. More recently, PyHMMER has emerged as a Python binding to HMMER, providing greater flexibility for integration with modern bioinformatics workflows and enabling direct manipulation of HMM objects within Python scripts [35].

Experimental Protocols for TIR-NBS-LRR Gene Identification

Standard Workflow for Genome-Wide Domain Screening

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for identifying and characterizing TIR-NBS-LRR genes using HMMER and Pfam domain models, synthesized from multiple published studies [13] [3] [34]:

Step 1: Domain Model Acquisition

- Retrieve the NBS (NB-ARC) HMM profile (PF00931) from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) [3] [34]. This conserved domain serves as the foundational model for identifying NBS-LRR genes.

- Additionally, obtain HMM profiles for associated domains: LRR (multiple accessions including PF00560, PF07723, PF12799, PF13516, PF13855, PF14580), TIR (PF01582), and RPW8 (PF05659) for comprehensive classification [6].

Step 2: Initial HMMER Search

- Execute an HMMER search (hmmsearch or jackhmmer) against the target organism's proteome using the NB-ARC domain profile. Studies typically employ an E-value cutoff ranging from < 1×10â»Â²â° for high stringency [3] to < 1×10â»Â² for broader identification [6].

- Alternatively, perform a BLASTP search using NB-ARC seed sequences from Pfam as queries with an E-value threshold of ≤ 1×10â»Â² as a complementary approach [6].

Step 3: Candidate Sequence Verification

- Extract all candidate sequences identified in the initial search and subject them to domain verification using the Pfam database, SMART tool (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), and NCBI's Conserved Domain Database (CDD) [3] [34].

- Remove duplicate entries and filter for sequences containing complete NBS domains to ensure analysis of functionally relevant genes [26].

Step 4: Classification and Subfamily Determination

- Classify verified NBS-LRR genes into subfamilies based on their domain architecture:

- Use COILS server (with threshold 0.1) or similar tools to identify coiled-coil domains that may not be detected by HMM profiles alone [6].

Step 5: Advanced Characterization

- Conduct phylogenetic analysis using maximum likelihood methods (e.g., IQ-TREE, MEGA) on aligned NB-ARC domain sequences to elucidate evolutionary relationships [3] [6].

- Perform gene structure analysis examining exon-intron organization using genomic DNA sequences and annotation files [3].

- Analyze cis-regulatory elements in promoter regions (typically 1.5 kb upstream of start codons) using databases such as PlantCARE [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for Domain Analysis

Table 2: Essential Bioinformatics Tools and Resources for NBS-LRR Gene Identification

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in NBS-LRR Research |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER Suite | Profile HMM construction and searching | Primary tool for identifying NBS-encoding genes using PF00931 model [13] [3] [34] |

| Pfam Database | Curated collection of protein domain models | Source of NB-ARC (PF00931) and related domain HMM profiles [3] [34] |

| SMART | Protein domain annotation | Validation of identified domains and detection of additional structural features [34] [6] |